Полная версия

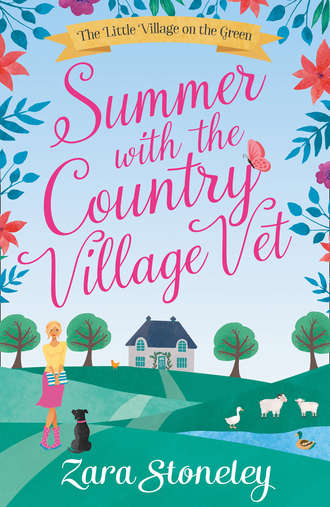

Summer with the Country Village Vet

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers

www.harpercollins.co.uk

HarperImpulse an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperImpulse 2017

Copyright © Zara Stoneley 2017

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover images © Shutterstock.com

Cover design by Micaela Alcaino

Zara Stoneley asserts the moral right

to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are

the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to

actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is

entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International

and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

By payment of the required fees, you have been granted

the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access

and read the text of this e-book on screen.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted,

downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or

stored in or introduced into any information storage and

retrieval system, in any form or by any means,

whether electronic or mechanical, now known or

hereinafter invented, without the express

written permission of HarperCollins.

ISBN: 9780008237967

Ebook Edition © June 2017

Version 2017-07-19

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

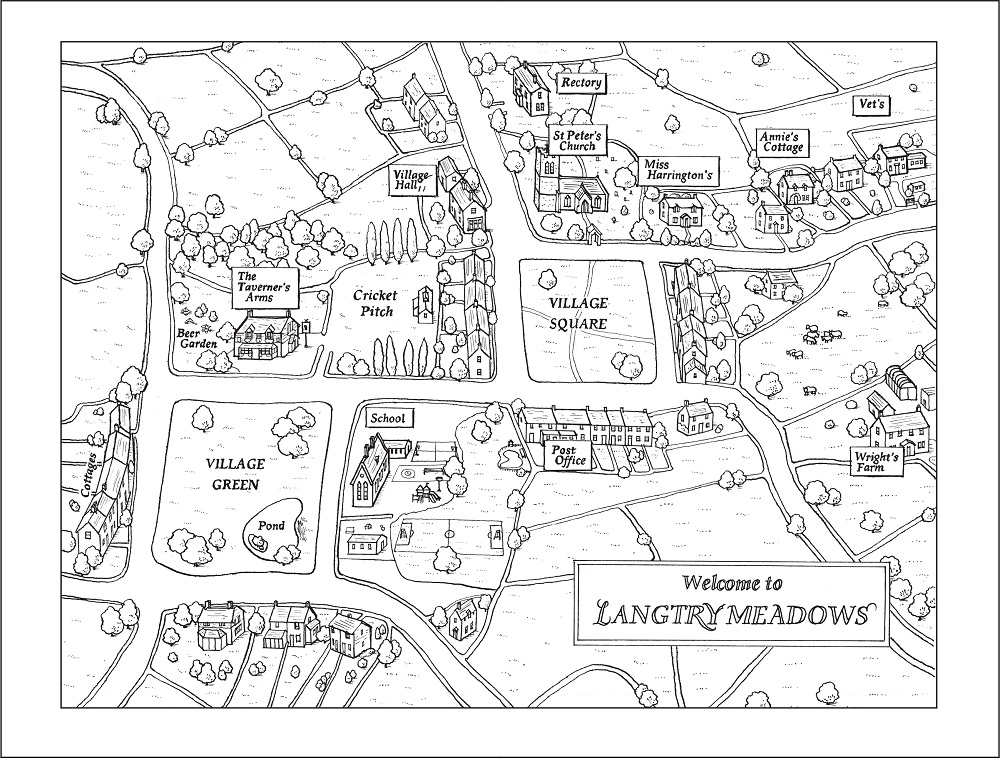

Map

A Note From the Author

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Acknowledgements

Also by Zara Stoneley

About the Author

About HarperImpulse

About the Publisher

‘It takes a big heart to help shape little minds’ Author unknown

To Anne, a teacher with a big heart.

A Note from the Author

Dear Reader,

Thank you so much for picking up this copy of Summer with the Country Village Vet, I hope you enjoy your visit to Langtry Meadows with Lucy and Charlie!

This book has been waiting to be written for a long time. I’ve always loved animals (I dreamed of being a vet and following in the footsteps of James Herriot), and you may have noticed that all my books feature at least one four-legged friend. But when I started writing, one quote kept springing to mind -

‘Never work with children or animals’ W. C Fields

I can quite understand the sentiments behind these words! Both can be unpredictable, scene-stealing, mischievous, temperamental – and never quite do what we expect (or sometimes want), but don’t we love them for it? They enrich our lives and touch our hearts. Young children and animals don’t judge; they give unconditional love, they forgive, teach respect, acceptance, and loyalty. They look to us to do the right thing, to take care of them – and can sometimes give us optimism, and a reason to keep going.

In short, they give us hope – and a few tears of laughter and sadness along the way as well. Which I hope this story also does.

Happy reading!

Zara x

Prologue

Three little words with the power to take her straight back to her childhood.

Termination of employment.

Lucy Jacobs stared at the words which were shouting out so much more. Failure. Not good enough. You don’t belong here. And she was suddenly that small, abandoned child in the playground again. Unwanted. Unloved. Alone.

Swallowing down the sharp tang of bile, she blinked to clear her vision. Smoothed out the piece of paper with trembling fingers that didn’t seem to belong to her. Nothing seemed to belong to her, everything was disjointed, unreal. Even the weak, distant voice that she vaguely recognised as her own.

‘No.’ Taking a deep breath, she shook her head to dismiss the image. She wasn’t a scared child. She was a grown woman now. ‘This is a mistake.’ Slowly the world came back into focus, even though her stomach still felt empty. Hollow. ‘This has got to be a mistake. You’re kidding me?’ Her words echoed into the uncomfortable stillness of the room.

The man opposite gave the slightest shake of his head, as though it was a silly question.

She’d never liked this room, or more to the point she’d never liked him.

Nobody got sacked on a school inset day. Did they?

She blinked hard, trying to ignore the way her eyes smarted and transferred her gaze to the carefully regimented line of pens, before forcing herself to look back up at him. David Lawson. The headmaster of Starbaston Primary School.

Not looking at him would be admitting defeat.

He looked back at her through cold reptilian eyes and still didn’t say a word.

‘But I’ve just finished my new classroom display!’ It was a stupid thing to say, but the only logical thought that was penetrating her fuzzy brain. ‘Ready for tomorrow.’ Tomorrow, the first day of term.

He finally shifted in his seat, his lips thinned and he stared at her disapprovingly. Then sighed. ‘You always do plan well ahead, don’t you?’

He said it as though it was a failing. Lucy felt her back straighten and her eyes narrowed, forcing the tears back where they belonged.

The fingers of dread that had been curling themselves into a hard lump in her chest were replaced with indignation. How dare he! The display was a triumph.

Last year’s fluffy lambs and cute rabbits had led to a cotton wool and glue fiasco she never wanted to repeat. How was she supposed to know that a six year old would come up with the idea of dipping the rabbit tails into the green paint pot intended for spring grass and stick the resultant giant bogey up his nose, and every other boy in the class would copy him? No doubt when she was old and grey the smarty pants would be a great leader, probably of some union that would bring the government to its knees, or more frighteningly he could become prime minister.

She’d learned from her mistake, and this year she’d been clever. With the help of Sarah, her never tiring classroom assistant, she’d cut a flower out for every single child and gone for the theme of April showers and May flowers. They had spent most of the day stapling the petals up on the boards, awaiting the children’s smiley self-portraits to be added in the centre over the next couple of weeks.

It had been hard work. It had been a total waste of time.

She stared at the headmaster, wishing she could wiggle her nose and make him disappear. He peered back over his glasses at her, and steepled his fingers, in much the same way he did when he was faced with a Year 6 girl who thought school rules about make-up (or more precisely the lack of it) couldn’t possibly apply to the top class, or Mrs Ogden who’d said if her Storm wanted to have white hair and pierced ears what did it have to do with him?

The head didn’t understand X-Men, he didn’t understand the society he was living in, or the staff who worked so hard to give the children a chance to live a better life. He understood balance sheets, not feelings and aspirations.

‘As you know,’ he paused, politician style, circled his thumbs – which right now she had a childish urge to grab hold of and bend back – ‘we did request offers for voluntary redundancy earlier in the year, but nobody,’ the thumbs stopped moving, and he studied her as though she was at fault, ‘came forward, and so unfortunately…’

‘But you can’t… I mean, why me?’ She crossed her arms and frowned. ‘I need this job, I’ve just bought new curtains.’ Gorgeous, shimmery, floaty new curtains. And it was more than curtains: she’d bought a whole house. A house that had stretched her to the financial limit, but given her the greatest feeling of satisfaction (apart from getting all of Year 2 to sit on their bottoms and listen at the same time) ever. Ever.

‘The Ofsted inspector labelled my lesson outstanding.’ She made a valuable contribution, she worked hard.

This just couldn’t be happening.

‘You can’t sack me.’

He tutted. Actually tutted, and looked affronted. ‘We,’ that flaming ‘we’ again, as though it meant he wasn’t responsible, ‘aren’t sacking you, Lucy.’ He paused again, politician style. ‘You are being offered an excellent redundancy package.’

‘Well that’s different then.’ He nodded, missing the sarcasm. ‘So offered means I can turn it down?’ She wanted to launch herself across his tidy desk and strangle him with his fake silk tie. It might be a sackable offence, but that didn’t matter now. Did it?

He carried on smoothly, oblivious of her evil intent. ‘No, I’m sorry it doesn’t. As I’ve just explained, we did ask for volunteers, and as nobody put themselves forward we have had to make a decision. We’ve followed the correct procedure.’ There was an unspoken ‘so don’t even think about challenging the decision’.

‘I don’t care about procedures.’ It was getting close to a toss-up between losing her temper and shouting, or bursting into tears. She bit down on her lip hard. No way was she going to give him the satisfaction of seeing her collapse into a mushy mess. That would be the ultimate humiliation. Even beating the getting sacked in the first place bit. ‘I’ve got a mortgage.’

He sighed as though she was being unreasonable. ‘I am sorry, Lucy. We do understand, we all have commitments, but unfortunately we,’ why did he keep blaming ‘we’ when it was very clearly his decision? He never had liked her, ‘have to make cuts. It’s inescapable. As you know education has been hit as hard as anybody.’ She caught herself nodding in agreement, and froze back into position. ‘We have tried to do this as fairly as possible, and as the most recent addition to the staffing at the school, then I’m afraid you were the—’

‘But what about Ruth?’ It came blurting out of her mouth before she could stop herself. She really didn’t want to point the finger at anybody else, but this was her future at stake.

‘We need to balance the accounts Miss Jacobs,’ oh God, he’d reverted to calling her Miss, there was no way out of this, ‘and as Ruth is very much a junior member of staff, her salary is, how do I put this? Commensurate with her experience.’ He put his hands flat on the desk and leaned back, mission accomplished. She’d never particularly liked David Lawson, with his slightly pompous air, and sarcastic comments if anybody dared interrupt his staff meetings to offer constructive criticism, but now there was something stirring inside her that was close to loathing.

‘And my experience doesn’t count for anything? You employed me because—’

‘It’s a fine balancing act, my dear.’ Now he’d moved on to patronising, which he probably thought was consoling. ‘It’s complicated.’

‘Try me.’

‘The finances of the school are not something you should concern yourself with, Lucy.’ He shook his head. Back to calling her Lucy and adopting his avuncular uncle act.

Obviously, she was smart enough to take responsibility for developing the young minds that would be tomorrow’s leaders, scientists and all round wonderful people, but he did not consider she had the mental capacity to understand the balance sheet of a primary school. Despite the fact she had a maths degree.

‘Now, you are bound to be upset and need to let this sink in, so to avoid any unpleasantness I had somebody clear your belongings from your classroom. There’s a box at reception, I’m sure everything is in there, but if there’s anything missing please do call Elaine and she will arrange delivery.’ He stood up, smiled like a hyena about to pounce, and held out a hand. Which she automatically shook, then realised she’d conceded defeat. ‘I do wish you well Lucy, you’ve done an excellent job with your little people and another school will benefit hugely from our loss.’ He withdrew the hand, obviously relieved that his ordeal was over, and hers had just begun. He’d handed over the baton. ‘And here is a letter with the terms of your redundancy, I’m sure you’ll find it all in order. Close the door on the way out will you please.’

He’d already sat down again, his head dipped to study the papers on his desk so that he could avoid her. She’d been dismissed.

Lucy stood up and was shocked to realise her legs were trembling. Her whole body was quaking. She fumbled with the door handle, tears bubbling up and blurring her vision, her stomach churning like the sea in a storm. This wasn’t her. She didn’t do wobbly and tears in public.

She felt sick.

***

Lucy put the surprisingly small box, which represented two years of tears, tantrums and triumphs (usually the pupils, occasionally hers) at Starbaston Primary School on the kitchen table. She could scream loudly and set next doors dog off barking, or she could make a cup of tea.

The bright, modern kitchen had, until now, given her only pleasure, but now she felt flat as she switched the fast-boil kettle on and dropped a tea bag into the ‘Best Teacher’ mug that Madison, a Year 2 pupil, had presented to her last Christmas.

She stared out at the small but immaculate patch of garden, her patch with not a weed in sight, and the hollow emptiness inside her grew.

Around the edges of the neat square of grass, the crocus shouted out a bright splash of colour, goading the pale nodding heads of the snowdrops. Soon the daffodils would appear, and she’d already bought sweet pea seeds to sow with her class (the only flowers many of them would see close up) so that she could bring a few of the seedlings home and brighten up the fence that separated her garden from her neighbours.

She’d had it all planned out. She’d had her whole life planned out.

Tea slopped out of her mug as she stirred it mindlessly, the events of the last year spiralling on fast-forward in her mind, and bringing a rush of tears to her eyes.

They brimmed over and she scrubbed away angrily at them with the heel of her hand. Tea and sympathy was one thing, tea and self-pity was altogether different. Pathetic. She needed to get a grip. This was just a blip, things like this made you stronger, more determined. The failures were what made you who you were; the only people who didn’t fail were the ones that never did anything.

The garden blurred as she wrapped her hands round the mug and took a deep breath, willing the lump in her throat to go away. If she hadn’t moved to Starbaston, if she’d just settled for her old, mundane job with no job prospects she wouldn’t be jobless. But she would never have been able to buy her home either.

Buying this house had been the biggest, best, scariest thing she’d ever done. She’d only been teaching at Starbaston for a year when they’d given her the promotion they’d hinted about at the interview. She’d got home from work, re-read the letter about twenty times, let out a whoop and started looking at the estate agents. Not that she didn’t already have a good idea of the houses for sale in the area.

She’d scrimped and saved ever since she’d graduated, well even as a student, rarely going out and only buying clothes that she really needed, determined to have enough money for a deposit on a small house in her bank account ready for the day that her income level meant she could take the plunge. And she knew exactly what she wanted, and had a pretty good idea of the size of salary she needed to afford it. It would be hers. Nobody would be able to take it away. She’d never again feel like she didn’t belong.

Her friends had laughed, but Lucy knew it was the right thing for her. She’d been eight years old when life as she knew it had been ripped into shreds. When her and Mum had moved from their comfortable village home into a scruffy rented terraced house with peeling paint and neighbours who peed on the fence. She’d lost everything: her dad, her dog, her lovely room, even her best friend. She was a nobody; nobody wanted her, and she didn’t belong anywhere.

She’d wanted her home back. She’d wanted her mother how she used to be – always there when she needed her, in the playground each day with a smile when she came out of school. She’d wanted her dog, Sandy, to play with. She’d wanted her room with all her books and toys, her garden with the swing she’d sit on for hours. She’d wanted her friend Amy to sit with her under the big tree in the school playground. She’d even wanted her dad back, even though he could be cross if she made a mess, and insisted she practise the piano every day.

Instead she’d been alone.

Her mother always out, working all hours in dead-end jobs trying to make ends meet, and never having time to tidy or clean the embarrassingly messy house. She’d kept her own room tidy, because Dad liked tidy, and maybe he’d come to see them if she kept it nice. She’d dreamed that one day he would, and he’d take them home and everything would go back to normal.

He never came. Gran told her to forget him; he’d remarried. Her lovely bedroom belonged to somebody else now, and there was no going back.

Amy never replied to her letters – her mother probably wouldn’t have let her visit their scruffy new home anyway. And the kids at her new school laughed at the way she spoke and wouldn’t let her join in with their games, turning their backs on her if she ever dared pluck up the courage to edge her way over to them. She gave up in the end.

Life got better when she moved to high school and found friends. In the big impersonal city school she felt less alone, there were more people like her – struggling to find a place to belong.

But she still lived on the roughest estate, in the scruffiest house. And she promised herself that one day she would have a decent job, and a house of her own. A clean tidy home, on a clean tidy estate where she felt in control, a home that nobody could take away from her.

And the sacrifices had seemed worth it. Until now.

How could this have happened to her? She’d done everything right, she’d worked hard, she’d had a plan – and had been discarded, thrown out because she was too qualified. Too expensive.

She wiped the fresh tears away angrily. Except this time it was different. She was in control, she wasn’t some kid who had no say in the matter, and she did belong here. She did.

She fished into the box that represented her time at Starbaston and pulled out a pen pot (empty), a packet of ‘star pupil’ stickers, a box of tissues, a spare pair of tights, an assortment of plasters, notepad and then spotted a slip of paper. Which had been placed so the eagle-eyes of the headmaster’s secretary didn’t spot it.

‘Can’t believe they did this to you, don’t know how I’ll cope without you Miss Crackers. Love Sarah x’

The lump in her throat caught her unawares and Lucy crumpled up the note in her fist and hung on to it. It had been one of their many jokes, she was Miss Cream Crackers after little Jack, he of the hand-me-down uniform and mother with four inch heels and a scary cleavage, had declared on her first day at the school that ‘he could only eat them Jacobs cracker things with a lot of butter spread on them or they made him cough’ and did she make them when she got home from school?

Jokes got them through the day.

She didn’t know how she was going to cope either. The feeling inside her wasn’t just upset, it was more like grief, as though a chunk of her hopes, her future, had been torn from her heart.

The cup of tea wasn’t making her feel better. Halfway through her drink the feeling of grief had subsided, but it had been replaced with something worse.

She thought that she’d left the waves of panic behind – along with the spots, teenage crushes and worries that she’d never have friends or sex – but now they started to claw at her chest. She closed her eyes.

She just had to breathe. Steadily. In, out, the world would stop rocking, her heart wouldn’t explode, she wasn’t going to die. Everything would be fine.

She would think about this logically. Sensibly. With her eyes shut.

The redundancy money would cover the bills for a while, but she urgently needed to find another job before it ran out. There was no way she was ever, ever, going to go back to living in that horrible neighbourhood she’d been brought up in. It hadn’t been her mother’s fault that she hadn’t time to keep on top of the house or garden, and that they could never afford anything new, but Lucy wanted her life to be different.

Putting her mug of tea on the table, she flipped open her laptop. She wasn’t going to mess around, or waste another second.

She’d show David bloody Lawson. She’d get another job, a better job, a job where the headmaster wasn’t a self-satisfied arse who didn’t give a monkeys about his staff or his pupils. Blinking away the mist of unshed tears she typed two words into the browser ‘teaching vacancies’, and hit the enter key with an angry jab.

***

Lucy opened her eyes with a start. It was dark. One cheek was damp and plastered to her keyboard. She probably had an imprint of the keys on her face. She sat up slowly and blinked.

The outside security light, which must have woken her up, went off and plunged the kitchen into darkness.

She sighed and stood up, wincing as a pain shot between her shoulder blades. Her back felt stiff as a board, she had a horrible dry taste in her mouth and her hair was sticky against her cheek from either dribble or tears. Or both. So, life was going well. She’d only been jobless for a few hours and look at the state of her.

So much for the no tears strategy, she’d failed there as well. But did crying in your sleep count?

This would look better in the morning. It had to. Before falling asleep she’d looked at every conceivable (and inconceivable) teaching vacancy website and come up with a big fat zero. The trouble was, teachers were being laid off faster than they were being taken on. And even supply jobs were thin on the ground, as an increasingly large number of people (many with more experience than she had) competed for them.