Полная версия

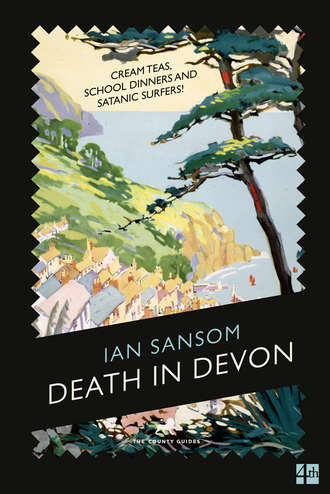

Death in Devon

We entered into a thick fug and hubbub of tobacco being smoked, of jokes being cracked, of sherry glasses tinkling, of the crackle of corduroy and tweed, and of the infernal sound of a gramophone playing music of a Palm Court trio kind – ‘the music of the damned’, Morley would have called it – but upon our entrance all noise abruptly ceased. From deep within the fug a dozen or so pairs of eyes fixed upon us. Only the Palm Court trio played on: the dreaded sound of Ketèlbey’s ‘In a Persian Market’, a tune regarded by Morley with particular horror (‘self-aggrandising nonsense’ is his memorable description in Morley’s Lives of the English Composers (1935)). The room also had the most extraordinary smell: rich, thick and rank. I couldn’t quite put my finger on it, but in this stench, and to the sound of Ketèlbey’s self-aggrandising nonsense, the gathered crowd smoked and stared at us, breathing as one.

‘Oh don’t mind us!’ said Miriam, entirely undaunted, and indeed clearly relishing the attention. ‘At ease, at ease. We’re only the school inspectors.’ And then turning to me, in the sotto voce remarking manner that she had unfortunately inherited from her father, she said, ‘Not sure that we’ll pass them, eh, Sefton? Seem like rather a rum bunch, wouldn’t you say?’ Clearly meant as a joke, the silence that greeted these remarks might best be described as stony, and the atmosphere as icy – until, as the sound of Ketèlbey faded away, a man boldly separated himself from what was indeed a rum bunch and came towards us, like a tribal leader stepping forward to greet the arrival of Christian missionaries.

A sodality of pedagogues

‘I’m Alexander,’ he said, ‘but everyone calls me Alex. Delighted to meet you.’

Alex shook my hand in an appropriately brisk and friendly manner but he took Miriam’s hand with a rather theatrical flourish, I thought, and then he kissed it, lingering rather, bowing slightly – all entirely unnecessary. He then gave a quick glance to his colleagues, which seemed to be the signal for them to resume their conversations. Sherry glasses were once again raised, and someone set the Palm Court trio back upon their damned eternal gramophone scrapings. The natives were calmed and reassured.

Alex was tall, long-legged, dressed in a dark double-breasted suit, and had what one might call confiding eyes. Miriam – who knew the look – offered her confiding eyes back. I feared the worst. There was no doubt that Alex had a commanding presence: he rather resembled Rudolph Valentino, though with something disturbingly super-sepulchral about him that suggested not the Valentino of, say, The Sheikh, but rather a Valentino who had recently died and then been miraculously raised from the dead. He also had the kind of deep, capable voice that suggested to the listener that one had no choice but to trust and obey him, and an accompanying air of bold determination, of knight-errantry, one might say, as if having just returned from the court of King Arthur, in possession not only of the Holy Grail but of the blood of Christ itself. I conceived for him an immediate and most intense distaste. Miriam, on the other hand, was clearly instantly smitten and the two of them fell at once into deep conversation.

Feeling rather surplus to requirements, and dreading an evening of talking about the state of modern education with a group of teachers – having long since forsworn all such utterly pointless conversations – I excused myself to go and arrange for the unloading of the Lagonda.

Out in the school’s forecourt I lit a cigarette and gazed up at the building. The place had a medieval aspect about it, like some kind of monastery, rather ponderous in style, and yet also at the same time strangely promiscuous, self-fertile almost, appearing to consist of numerous buildings growing into and out of one another, clambering over and upon itself with gable upon gable upon turret upon high tiled roof, writhing and reaching up towards the dark heavens above.

As I glanced up and around I fancied that I was being watched – and indeed for a moment I thought I saw the small white faces of young boys pressed up against mullioned window panes in the furthest and highest corners of the buildings. But when I turned again, having stubbed out my cigarette, they had gone.

The sensation of being watched, however, strongly persisted: it was almost as if someone had clapped me on the shoulder, or slapped me on the back; I felt eyes upon me. The air felt cold, as if someone had rushed close by. I turned quickly again, this time looking down around the forecourt and out towards the fields – and there in the moonlight I saw a man. He stood by the hedge beyond the lane, under the shelter of a tree.

‘Hello?’ I said instinctively.

‘Hello,’ he replied softly, his voice carrying clearly across the still night air.

‘Are you watching me?’ I asked. I didn’t know what else to say.

He stepped forward then, out from the shade of the tree, and I saw that he was dressed in old, stained muddy clothes – pig-skin leggings and an old battledress coat – with an unlit lantern in his hand. He was perhaps in his early twenties, with a light beard fringing his cheeks, a grey cap upon his head.

‘You’re out walking?’ I asked.

‘No,’ he said.

‘Well, who are you and what are you doing?’ The man struck me as a reprobate.

‘Who am I? I might be asking you the same, sir. Who are you? And what you be dwain? You a parent?’

‘No.’

‘Teacher?’

‘No.’

‘Who are you then, sir, and what you be dwain? You’re not from round here.’

‘No. That’s correct. My name’s Stephen Sefton and I’m here with Mr Swanton Morley, who is giving the Founder’s Day speech tomorrow.’

‘Is that right?’

‘Yes. And you are?’

‘I,’ he said slowly, ‘am Abednego.’

‘Ha!’ I couldn’t help but laugh. ‘Really? And you don’t happen to have two brothers named Shadrach and Meshach I suppose?’ He did not answer. He now stood no more than a few feet away from me, staring at me hard. I could smell cider on his breath. ‘Well, and what’s your business here this evening, Abednego, if I might ask?’

‘I’m watching the comings and goings,’ he said.

‘I see. You’re the night watchman, then, or a porter?’

‘You might say that.’

‘So Dr Standish would be aware of your activities?’

‘Standish knows all about me. And we know all about him.’

‘Good,’ I said, not entirely reassured, but wishing to be in conversation with this odd young fellow no longer. ‘Well, I’m just unloading the car here …’

He had already turned and walked away.

The contents of the Lagonda eventually unloaded into the school entrance hall, I separated my own travelling items from Miriam’s and Morley’s and picked up the Leica, fancying that I might perhaps take some photographs of the buildings. But as I was about to do so a loud gong sounded, summoning the teachers to dinner. As they flooded through the hall I found myself caught up among them as they trooped towards the dining room. Alex, walking alongside Miriam, spotted me with the camera and paused on his way past.

‘Camera fiend are we, Mr Sefton?’

‘I just take a few photographs,’ I explained. ‘For Mr Morley’s books.’

‘I’m a keen photographer myself. We have a modest little darkroom down in the basement if you’d like to see it some time.’

‘Tomorrow perhaps.’

‘I think you’ll be impressed,’ he said confidingly. ‘I think we may have many interests in common, Mr Sefton.’ And then he swept Miriam before him into dinner.

CHAPTER 6

RECOMMENDATIONS OF WHERE TO VISIT

WE ENTERED A VAST HALL and shuffled up onto a dais, around a long oak refectory table that bore the scars of age and half a dozen wax-encrusted candelabras. The hall was suffering from a split personality: it was a room divided among itself. Below and beneath the grand oak refectory table on its dais, set at right angles, were rows of rough pine trestles and cheap steel chairs, clearly of an inferior kind. The walls sported crude brown-painted wainscoting below, but vast swathes of old William Morris paper above. There were enough fireplaces to be able to warm the place on the coldest of evenings, and a scattering of three-bar electric fires which might do no better than warm the feet. Exquisite crockery and cutlery were laid on our table, along with battered enamelware jugs and chipped, thick glass tumblers. The unmistakable sweet smell of wax and polish: and the underlying stench of sweat and cabbages. All the usual contradictions, in other words, of the English public school.

Mr Woland Bernhard and his excellent and idiomatic English

I found myself next to the maths master, a Mr Woland Bernhard, who was possessed of boyish good looks and tremendous enthusiasm. He was also German: ‘But not of the bad kind!’ he was quick to point out. He spoke, of course, excellent and idiomatic English. ‘Yes, yes,’ he insisted, when I gestured to take the space next to him, ‘take a pew, take a pew.’ Before we had a chance to take our proverbial pews, the headmaster spoke.

‘Ladies and gentlemen, we are privileged to have with us this evening my dear friend Mr Swanton Morley, known to many of you no doubt as the People’s Professor. One might say that Mr Morley is in the same business as us here at All Souls: the education of the ignorant and the—’

‘Ineducable,’ quipped one of the teachers, to the delight of many of the others.

‘Thank you, Mr Jones,’ said the headmaster. ‘As you know, I invited Mr Morley here to give tomorrow’s Founder’s Day address’ – there was some mumbling and grunting around the table at this, I couldn’t tell whether in approval or disgust – ‘our very first Founder’s Day at our magnificent new location here at Rousdon. I wonder if Mr Morley might like to say the grace for us?’

There was no need to ask: never one to miss an occasion for preaching or performance, Morley ceremonially bowed his head, took a deep breath, and delivered a faultless grace. In Latin, naturally:

Exhiliarator omnium Christe

Sine quo nihil suave, nihil jucundum est:

Benedic, quaesumus, cibo et potui servorum tuorum,

Quae jam ad alimoniam corporis apparavisti;

et concede ut istis muneribus tuis ad laudem tuam utamur

gratisque animis fruamur;

utque quemadmodum corpus nostrum cibis corporalibus fovetur,

ita mens nostra spirituali verbi tui nutrimento pascatur

Per te Dominum nostrum.

‘Very good,’ said my mathematician friend, settling into his chair. ‘A classicist, your friend?’

‘Of a kind,’ I agreed. Morley’s stock of Latin tags, sayings and graces was seemingly inexhaustible, though his precise grasp of the grammar of any language other than English was, according to some critics, rather uncertain. He did not believe, for example, in what he called ‘traditional grammar’, propounding instead what he called a ‘theoretical grammar’, which he thought applied to all languages equally. This meant that he spoke Spanish as if it were English, and French as if it were German. He was also extremely disparaging of anything resembling what he called ‘punctuational patriotism’, insisting at all times on using only the very simplest of punctuation marks: he despised my frequent recourse to colons and dashes, which he felt were entirely unnecessary and a barrier to world peace and understanding. His ideas on the subject – which can be found in Morley’s Modern Multilinguist (1928) – had been formed through his correspondence with Mr Ludwik Zamenhof, the creator of Esperanto, and a man who Morley regarded as a kind of secular saint.

‘Now, do tell me, what do you think of our new school, Mr Sefton?’ asked my new German friend, whose manners and whose grammar were both impeccable.

‘It is quite lovely,’ I said, not untruthfully, ‘what I’ve seen of it.’

‘Yes,’ he agreed, cracking open a starched but rather stained napkin and tucking it into his shirt collar. ‘You are correct. It is lovely. And tomorrow you will enjoy also the farm and the dairy and the pumping house. You may know we also have a bowling alley, for the boys, and a rifle range. Tennis courts. And our own little observatory.’

‘Really?’ I said, not paying much attention to him. I was too busy watching Miriam across the table: she was busy flirting with Alexander.

‘We have everything we need here. It is our own little community.’

‘Very good,’ I said.

‘And Dr Standish is our leader,’ he added.

‘Yes.’

‘An excellent headmaster,’ he said. ‘Despite what some people say.’

‘I see.’ Parts of this conversation I must admit I missed entirely.

‘A headmaster must exert total control over a school. Otherwise …’

His ‘otherwise’ trailed off rather, at the very moment at which plates of soup were set before us, and I looked away from the playful Miriam and Alexander and returned my attention to my mathematical friend.

‘Sorry? You were saying?’

‘Otherwise …’

‘Uh-huh. “Otherwise”?’

‘Otherwise? Well. A good leader must be feared and respected,’ said my friend, factually. Perhaps because of his accent, or perhaps because I hadn’t been listening closely to what he was saying, I wasn’t entirely sure if he was referring to the school or to a nation. ‘But. A glass of our modest vin de table, Mr Sefton?’

‘Thank you,’ I said.

He poured and we shared a toast.

‘To knowledge!’ he said.

‘Indeed.’

‘Now, eat!’ he said.

I had a bellyful of People’s Mints and a day of Morley behind me. I did not argue.

Dishes were served and conversations undertaken. At the head of the table, deep in reminiscence, Morley and the headmaster carried on like long-lost brothers. The meal itself was a curious affair. Dr Standish was apparently a recent convert to the cause of vegetarianism, and was determined that all meals in the new school were to be prepared with ingredients from their own farm. Setting the example, he dined, therefore, on a small dish of carrots and a bowl of new potatoes that looked particularly dull and surly – grey-brown, speckled, about the size of bantam eggs, and rather few in number. For the rest of us, however, there were plates of steak, grilled lamb and whole chickens, fresh bread and pats of butter the size of cricket balls: a veritable feast.

On my right sat the school nurse, the woman who had greeted us on our arrival, a Miss Horniman. She was a young, round neurotic thing who wore Harold Lloyd glasses and picked at her food absent-mindedly like a schoolgirl and who kept telling me how terribly lucky she was to have a job at the school, and how brilliant and creative were all the staff, particularly Alexander, of course, with whom she occasionally exchanged glances across the table – just as I exchanged glances with Miriam – and with whom she was clearly in love. Her paean to All Souls, to its staff and pupils, and to the extraordinary Alexander in particular soon became rather tiring.

‘He takes photographs you know,’ she said. ‘He’s terribly modern and up-to-date. He’s taken photographs of all of us here in the school.’ I momentarily entertained an image of her lounging on a divan, her innocence protected with a carefully draped Chinese shawl, or perhaps a strategically placed puppy, her eyes glowing like ruby sparks behind the Harold Lloyd glasses, and Alex hovering over her greedily with his lens …

‘Really?’ I said. ‘I also take photographs—’

‘And he paints,’ she said. ‘He’s influenced by the surrealists, you know.’

‘Yes. He certainly looks like a man who might be influenced by the surrealists.’

‘And he makes sculptures – clay models. Bronzes.’

‘Is there no end to his talents?’ I asked. This was not, I must confess, intended as an entirely serious question, but Miss Horniman took it entirely as such.

‘Really, I don’t think there is,’ she said, ‘he is so extraordinary.’ She then duly launched into a list of his various other accomplishments, including his athletic prowess, his culinary skills – he was reputed both to be able to boil spaghetti – ‘Italian spaghetti!’ she exclaimed – and to make a fine mayonnaise – and his amazing ability on the recorder. ‘And he plays the organ!’ she concluded. ‘He writes his own tunes!’

‘He is like J.S. Bach himself,’ I said.

‘Yes,’ she agreed.

‘Crossed with Pablo Picasso and Auguste Escoffier.’

‘Exactly like J.S. Bach crossed with Picasso,’ she said. ‘And Escoffier! Exactly!’

All the time, opposite us, Alex and Miriam continued deep in conversation, Miriam occasionally looking across the table in my direction, with what could only be described as a mischievous glance.

Tearing through a slice of perfectly pink lamb, I turned back to my German friend, Woland, who proceeded to discourse enthusiastically upon his love of the English countryside, explaining that he had hiked the length and breadth of Devon with nothing but his trusty knapsack on his back and the goodwill of the local people to guide him. Unaware of the torrent of tiresome trouble I was about to unleash, I then foolishly revealed that we were here not just for Founder’s Day but were intending to explore Devon for the second volume of The County Guides series, and I asked, innocently, if perhaps he could recommend anywhere that we should visit? This was a terrible, terrible mistake.

In later years I learned not to mention our purpose to others, in case what happened then happened again – though of course it often happened anyway. Everywhere we visited during our time together working on the books we found people excessively proud of their counties, as though of some prize cow, or a local cheese, and intent upon offering recommendations of where to visit in order best to enjoy the local delights. It was like listening to parents extolling the virtues of their children – which is to say, deeply tiresome.

‘Ah!’ said Woland, flexing his fingers in preparation for what was clearly going to be a serious bout of totting up. ‘Recommendations of where to visit?’

‘Yes, that would be very helpful, if you have any.’

‘Beer,’ he said definitively.

I thought I’d misheard him.

‘Beer?’ I said. ‘No thank you, I’m fine.’ We were by this stage in the meal drinking a red wine so sweet that it might almost have been used for communion.

‘Nein! Nein! Nein! Beer. Beer?’

‘Beer?’

‘A fishing village, not far from here, just a few miles. Surely you know Beer, Mr Sefton? I thought it was famous in England? The stone from Beer, it has been used in the Tower of London?’

‘Of course. The stone from Beer, yes, used in the—’

‘And it has a lovely sheltered bay.’

‘Good.’

‘And white cliffs – and a stream that runs down the main street, leading to the beach.’

‘Sounds absolutely lovely.’

‘And of course the caves.’

‘The caves?’

‘Yes, the quarry caves. Would you prefer for me to write this down?’

‘No, it’s fine. I can remember, thank you.’

‘Good. So. When they have quarried the limestone it has left these … what would you say? Caves?’

‘Caverns?’

‘Yes, caverns. Used for smugglers. Wonderful. The stone of Beer was first quarried for the Romans, I think.’

‘Really?’ I rather wished I was drinking beer, rather than hearing about it.

‘Very big underground rooms, chambers. The rooms are the reverse image, you see, of the great halls and cathedrals quarried from them.’

‘Yes, that does sound very interesting,’ I said, feigning enthusiasm.

‘Where else?’ wondered my friend. ‘Where else would you like to visit?’

‘I’m not sure,’ I said. ‘I think we probably have an itinerary that will see us through …’

He called across the table to a thin man, Mr Jones, a Welshman, who had earlier made the quip about the ineducable, and who was now engaged in the business of dismembering half a chicken. Woland explained to him the purpose of our visit.

‘Beer, Jon. They are visiting Beer. But where else should they visit?’

‘The Royal Oak at Sidbury?’ said the hilarious Jon Jones, the Welshman, pausing momentarily in his chicken-parting. ‘And the Turks Head at Newton Poppleford?’

‘Not just pubs, Jon!’

‘Only joking,’ said Jon, obviously, his mouth now full. ‘What about the caves? They should probably visit the caves.’

‘Yes, I have already suggested the caves,’ agreed my German friend. Jon Jones the Welshman had by this time nudged the woman on his left, and explained our purpose to her, and she had dutifully nudged the person on her left, who had explained our purpose to them, and etcetera, until soon I had recommendations from almost everyone seated at the table. In south Devon alone we were encouraged to visit Branscombe (‘Thatched forge, terribly pretty, longest village in the country’), Budleigh Salterton (‘You simply must go to Budleigh!’), Colyton and Colyford. Exmouth. Seaton. Shute Barton Manor. Ilfracombe. The moors. Great houses. Battlements. Tudor gatehouses. The usual.

Fortunately, by the time we had reached dessert – of which there was an abundance, including huge fruit flans of cherry, raspberry and apple, with bowls of thick cream – I had managed to move the conversation forward. Unfortunately, the conversation we moved forward towards was education, a topic of course of great importance but frankly of strictly limited conversational interest, but upon which and about which my dear German friend, mid-flan, was very keen to offer his many insights.

‘You see, with teaching it is as it is with cooking, Mr Sefton.’ He clapped his hands together as he spoke, and then paused to ladle more cream into his bowl. ‘First’ – he clapped again – ‘you take your boy, yes?!’ He chuckled. ‘Some young barbarian with all the qualities of the natural savage – raw, if you like, yes? A hard apple, perhaps? Or a nut. A sour cherry. And then you chop him up, and you break him down, and you add your spices and your sugar and cream, and you combine him with all these other ingredients and – voilà!’ He held a spoonful of fruit flan aloft. ‘He becomes this delicious, delightful new thing. A young man!’

‘Quite,’ I said.

‘Good enough to eat!’ pronounced Woland, eating his spoonful of creamy flan.

Miriam called across the table; she had been taking a quiet interest in our conversation.

‘You do know Mr Sefton was a schoolmaster himself for a long time. Isn’t that right, Sefton?’

‘No?’ said the German, his mouth half full. ‘But you should have said! You know exactly what I am talking about.’