Полная версия

Mistress of Mistresses

‘Would you be ageless and deathless for ever, madam, were you given that choice?’ said the Duke, scraping away for the third time the colour with which he had striven to match, for the third time unsuccessfully, the unearthly green of that lady’s eyes.

‘I am this already,’ answered she with unconcern.

‘Are you so? By what assurance?’

‘By this most learn’d philosopher’s, Doctor Vandermast.’

The Duke narrowed his eyes first at his model then at his picture: laid on a careful touch, stood back, compared them once more, and scraped it out again. Then he smiled at her: ‘What? Will you believe him? Do but look upon him where he sitteth there beside Anthea, like winter wilting before Flora in her pride. Is he one to inspire faith in such promises beyond all likelihood and known experiment?’

Fiorinda said: ‘He at least charmed you this garden.’

‘Might he but charm your eyes,’ said the Duke, ‘to some such unaltering stability, I’d paint ’em; but now I cannot. And ’tis best I cannot. Even for this garden, if ’twere as you said, madam (or worse still, were you yourself so), my delight were poisoned. This eternal golden hour must lose its magic quite, were we certified beyond doubt or heresy that it should not, in the next twinkling of an eye, dissipate like mist and show us the work-a-day morning it conceals. Let him beware, and if he have art indeed to make safe these things and freeze them into perpetuity, let him forbear to exercise it. For as surely as I have till now well and justly rewarded him for what good he hath done me, in that day, by the living God, I will smite off his head.’

The Lady Fiorinda laughed luxuriously, a soft, mocking laugh with a scarce perceptible little contemptuous upward nodding of her head, displaying the better with that motion her throat’s lithe strong loveliness. For a minute, the Duke painted swiftly and in silence. Hers was a beauty the more sovereign because, like smooth waters above a whirlpool, it seemed but the tranquillity of sleeping danger: there was a taint of harsh Tartarean stock in her high flat cheekbones, and in the slight upward slant of her eyes; a touch of cruelty in her laughing lips, the lower lip a little too full, the upper a little too thin; and in her nostrils, thus dilated, like a beautiful and dangerous beast’s at the smell of blood. Her hair, parted and strained evenly back on either side from her serene sweet forehead, coiled down at last in a smooth convoluted knot which nestled in the nape of her neck like a black panther asleep. She wore no jewel nor ornament save two escarbuncles, great as a man’s thumb, that hung at her ears like two burning coals of fire. ‘A generous prince and patron indeed,’ she said; ‘and a most courtly servant for ladies, that we must rot tomorrow like the aloe-flower, and all to sauce his dish with a biting something of fragility and non-perpetuity.’

The Countess Rosalura, younger daughter of Prince Ercles, new-wed two months ago to Medor, the Duke’s captain of the bodyguard, had risen softly from her seat beside her lord on the brink of a fountain of red porphyry and come to look upon the picture with her brown eyes. Medor followed her and stood looking beside her in the shade of the great lime-tree. Myrrha and Violante joined them, with secret eyes for the painter rather than for the picture: ladies of the bedchamber to Barganax’s mother, the Duchess of Memison. Only Anthea moved not from her place beside that learned man, leaning a little forward. Her clear Grecian brow was bent, and from beneath it eyes yellow and unsearchable rested their level gaze upon Barganax. Her fierce lips barely parted in the dimmest shadow or remembrance of a smile. And it was as if the low golden beams of the sun, which in all things else in that garden wrought transformation, met at last with something not to be changed (because it possessed already a like essence with their own and a like glory), when they touched Anthea’s hair.

‘There, at last!’ said the Duke. ‘I have at last caught and pinned down safe on the canvas one particular minor diabolus of your ladyship’s that hath dodged me a hundred times when I have had him on the tip of my brush; him I mean that peeks and snickers at the corner of your mouth when you laugh as if you would laugh all honesty out of fashion.’

‘I laugh none out of fashion,’ she said, ‘but those that will not follow the fashions I set ’em. May I rest now?’

Without staying for an answer, she rose and stepped down from the stone plinth. She wore a coat-hardy, of dark crimson satin. From shoulder to wrist, from throat to girdle, the soft and shining garment sat close like a glove, veiling yet disclosing the breathing loveliness which, like a rose in crystal, gave it life from within. Her gown, of the like stuff, revealed when she walked (as in a deep wood in summer, a stir of wind in the tree-tops lets in the sun) rhythms and moving splendours bodily, every one of which was an intoxication beyond all voluptuous sweet scents, a swooning to secret music beyond deepest harmonies. For a while she stood looking on the picture. Her lips were grave now, as if something were fallen asleep there; her green eyes were narrowed and hard like a snake’s. She nodded her head once or twice, very gently and slowly, as if to mark some judgement forming in her mind. At length, in tones from which all colour seemed to have been drained save the soft indeterminate greys as of muted strings, ‘I wonder that you will still be painting,’ she said: ‘you, that are so much in love with the pathetic transitoriness of mortal things: you, that would smite his neck who should rob you of that melancholy sweet debauchery of your mind by fixing your marsh-fires in the sphere and making immortal for you your ephemeral treasures. And yet you will spend all your invention and all your skill, day after day, in wresting out of paint and canvas a counterfeit, frail, and scrappy immortality for something you love to look on, but, by your own confession, would love less did you not fear to lose it.’

‘If you would be answered in philosophy, madam,’ said the Duke, ‘ask old Vandermast, not me.’

‘I have asked him. He can answer nothing to the purpose.’

‘What was his answer?’ said the Duke.

The Lady Fiorinda looked at her picture, again with that lazy, meditative inclining of her head. That imp which the Duke had caught and bottled in paint awhile ago curled in the corner of her mouth. ‘O,’ said she, ‘I do not traffic in outworn answers. Ask him, if you would know.’

‘I will give your ladyship the answer I gave before,’ said that old man, who had sat motionless, serene and unperturbed, darting his bright and eager glance from painter to sitter and to painter again, and smiling as if with the aftertaste of ancient wine. ‘You do marvel that his grace will still consume himself with striving to fix in art, in a seeming changelessness, those self-same appearances which in nature he prizeth by reason of their every mutability and subjection to change and death. Herein your ladyship, grounding yourself at first unassailably upon most predicamental and categoric arguments in celarent, next propounded me a syllogism in barbara, the major premiss whereof, being well and exactly seen, surveyed, overlooked, reviewed, and recognized, was by my demonstrations at large convicted in fallacy of simple conversion and not per accidens; whereupon, countering in bramantip, I did in conclusion confute you in bokardo; showing, in brief, that here is no marvel; since ’tis women’s minds alone are ruled by clear reason: men’s are fickle and elusive as the jack-o’-lanterns they pursue.’

‘A very complete and metaphysical answer,’ said she. ‘Seeing ’tis given on my side, I’ll let it stand without question; though (to be honest) I cannot tell what the dickens it means.’

‘To be honest, madam,’ said the Duke, ‘I paint because I cannot help it.’

Fiorinda smiled: ‘O my lord, I knew not you were wont to do things upon compulsion.’ Her lip curled, and she said again, privately for his own ear, ‘Save, indeed, when your little brother calleth the tune.’ Sidelong, under her eyelashes, she watched his face turn red as blood.

With a sudden violence the Duke dashed his handful of brushes to the ground and flung his palette skimming through the air like a flat stone that boys play ducks and drakes with, till it crashed into a clump of giant asphodel flowers a dozen yards away. Two or three of those stately blooms, their stems smashed a foot above the ground, drooped and slowly fell, laying pitifully on the grass their great tapering spikes of pink-coloured waxen filigree. His boy went softly after the palette to retrieve it. He himself, swinging round a good half circle with the throw, was gone in great strides the full length of the garden, turned heel at the western parapet, and now came back, stalking with great strides, his fists clenched. The company was stood back out of the way in an uneasy silence. Only the Lady Fiorinda moved not at all from her place beside the easel of sweet sandalwood inlaid with gold. He came to a sudden halt within a yard of her. At his jewelled belt hung a dagger, its pommel and sheath set thick with cabochon rubies and smaragds in a criss-cross pattern of little diamonds. He watched her for a moment, the breath coming swift and hard through his nostrils: a tiger beside Aphrodite’s statua. There hovered in the air about her a sense-maddening perfume of strange flowers: her eyes were averted, looking steadily southward to the hills: the devil sat sullen and hard in the corner of her mouth. He snatched out the dagger and, with a savage back-handed stroke, slashed the picture from corner to corner; then slashed it again, to ribbons. That done, he turned once more to look at her.

She had not stirred; yet, to his eye now, all was altered. As some tyrannous and triumphant phrase in a symphony returns, against all expectation, hushed to starved minor harmonies or borne on the magic welling moon-notes of the horn, a shuddering tenderness, a dying flame; such-like, and so moving, was the transfiguration that seemed to have come upon that lady: her beauty grown suddenly a thing to choke the breath, piteous like a dead child’s toys: the bloom on her cheek more precious than kingdoms, and less perdurable than the bloom on a butterfly’s wing. She was turned side-face towards him; and now, scarce to be perceived, her head moved with the faintest dim recalling of that imperial mockery of soft laughter that he knew so well; but he well saw that it was no motion of laughter now, but the gallant holding back of tears.

‘You ride me unfairly,’ he said in a whisper. ‘You who have held my rendered soul, when you would, trembling in your hand: will you goad me till I sting myself to death with my own poison?’

She made no sign. To the Duke, still steadfastly regarding her, all sensible things seemed to have attuned themselves to her: a falling away of colours: grey silver in the sunshine instead of gold, the red quince-flowers blanched and bloodless, the lush grass grey where it should be green, a spectral emptiness where an instant before had been summer’s promise on the air and the hues of life and the young year’s burden. She turned her head and looked him full in the eye: it was as if, from between the wings of death, beauty beaconed like a star.

‘Well,’ said the Duke, ‘which of the thousand harbours of damnation have you these three weeks been steering for? What murder must I enact?’

‘Not on silly pictures,’ said she; ‘as wanton boys break up their playthings; and I doubt not I shall be entreated sit for you again tomorrow, to paint a new one.’

The Duke laughed lightly. ‘Why there was good in that, too. Some drowsy beast within me roused himself and suddenly started up, making himself a horror to himself, and, now the blood’s cooled, happily sleeps again.’

‘Sleeps!’ Fiorinda said. Her lip curled.

‘Come,’ said the Duke. ‘What shall it be then? Inspire my invention. Entertain ’em all to a light collation and, by cue taken at the last kissing-cup, let split their weasands, stab ’em all in a moment? Your noble brother amongst them, ’tis to be feared, madam; since him, with a bunch of others, I am to thank for these beggar-my-neighbour sleights and cozenage beyond example. Or shall’t be a grand night-piece of double fratricide? yours and mine, spitted on one spit like a brace of woodcock? We can proceed with the first today: for the other, well, I’ll think on’t.’

‘Are you indeed that prince whom reputation told me of,’ said she, ‘that he which did offend you might tremble with only thinking of it? And now, as hares pull dead lions by the beard—’

The Duke swung away from her a step or two, then back, like a caged beast. His brow was thunderous again. ‘Ever going on beyond your possession,’ he said, ‘beyond your bounds. ’Tis well I am of a cool judgement. There’s more in’t than hold up my hand, or whistle in my fist. Content you that I have some noble great design on foot, which in good time shall prove prodigious to ’em all: and once holding good my advantage over them, in their fall I’ll tempt the destinies.’

With an infinite slow feline grace she lifted up her head: her nostrils widening, the flicker of a smile on her parted lips: from beneath the shadow of long black lashes, half-moons of green lambent fire beheld him steadily. ‘You must not speak to me as if I were a child or an animal,’ she said. ‘Will you swear me all this?’

‘No,’ answered he. ‘But you may look back and consider of time past: I have been so sparing to promise, that (as your ladyship will bear me out) I have ever paid more than either I promised or was due.’

‘Well,’ she said: ‘I am satisfied.’

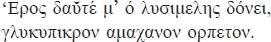

‘I must to the throne-room,’ said the Duke. ‘’Tis an hour past the hour of audience, and I would not hold ’em too long tarrying for me; ’tis an unhandsome part, and I use it but to curb the insolencies of some we spoke on.’ The Lady Fiorinda gave him at arm’s length her white hand: he bowed over it and raised it to his lips. Standing erect again, still unbonneted before her, he rested his eyes upon her a moment in silence, then with a step nearer bent to her ear: ‘Do you remember the Poetess, madam?—

As if spell-bound under the troublous sweet hesitation of the choriambics, she listened, very still. Very still, and dreamily, and with so soft an intonation that the words seemed but to take voiceless shape on her ambrosial breath, she answered, like an echo:

Once more Love, the limb-loosener, shaketh me:

Bitter-sweet, the dread Worm ineluctable.

‘It is my birthday, I am reminded,’ said the Duke in the same whispered quietness. ‘Will your ladyship do me the honour to sup with me tonight, in my chamber in the western tower that looks upon the lake, at sunset?’

There was no smile on that lady’s lips. Slowly, her eyes staring into his, she bent her head. Surely all of enchantment and of gold that charged the air of that garden, its breathless promise, its storing and its brooding, distilled like the perfume of a dark red rose, as ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Yes.’

III THE TABLES SET IN MESZRIA

PRESENCE-CHAMBER IN ACROZAYANA • THE HIGH ADMIRAL JERONIMY • THE LORD CHANCELLOR BEROALD • CARES THAT RACK GREAT STATESMEN • THE BASTARD OF FINGISWOLD • EARL RODER • CONFERENCE IN THE DUKE’S CLOSET • KING STYLLIS’S TESTAMENT • RAGE OF THE DUKE • THE VICAR SUSPECTED KING-KILLER • LEAGUE TO UPHOLD THE TESTAMENT.

MEANWHILE, for nearly two hours in the great throne-room in Zayana had the presence begun to fill against the Duke’s appearing. Now the fashion of that hall was that it was long, of a hundred cubits the length thereof and the breadth forty cubits. The walls were of pale hammered mountain gold, rough with an innumerable variety of living things graven some in large some in little, both hairy kinds and feathered, and scaly kinds both of land and sea, oftenest by twos and twos with their children beside their nests or holes, and the flowers, fruits, leaves, herbs and water-weeds native to each kind winding in the interspaces with a conceited formal luxuriance. Massy columns, four times a man’s height, of carved black onyx with milky veins, made caryatides in form of monstrous snakes, nine lengthwise of the hall on either side and four at either end. These supported on their hooded heads a frieze of tesselated jet four cubits deep, whereon were displayed poppies and blooms of the aloe and the forgetful lotus, all in a cool frail loveliness of opals and rose-coloured sapphires as for their several blooms and petals, and as for their stalks and leaves of green marmolite and chalcedony. Above this great flowered frieze the roof was pitched in a vault of tracery-work of ivory and gold, so wrought that in the lower ranges near the frieze the curls and arabesques were all of gold, then higher a little mingling of ivory, and so more and more ivory and the substance of the work more and more fine and airy; until in the highest all was but pure ivory only, and its woven filaments of the fineness of hairs to look upon, seen at that great height, and as if a sudden air or a word too roughly spoken should be enough to break a framework so unsubstantial and blow it clean away. In the corners of the hall stood four tripods of dull wrought gold ten cubits in height, bearing four shallow basins of pale moonstone. In those basins a child might have bathed, so broad they were, and brimming all with sweet scented essences, attar of roses and essences of the night-lily and the hyperborean eglantine, and honey-dew from the glades beyond Ravary; and birds of paradise, gold-capped, tawny-bodied, and with black velvet throats that scintillated with blue and emerald fire, flitted still from basin to basin, dipping and fluttering, spilling and spreading the sweet perfumes. The hall was paved all over with Parian marble in flags set lozenge-wise, and pink topaz insets in the joints; and at the northern end was the ducal throne upon a low dais of the same marble, and before the dais, stretching the whole width of the hall, a fair great carpet figured with cloud-shapes and rainbow-shapes and comets and birds of passage and fruits and blossoms and living things, all of a dim shifting variety of colours, pale and unseizable like moonlight, which character came of its cunning weaving of silks and fine wools and intermingling of gold and silver threads in warp and woof. The throne itself was without ornament, plainly hewn from a single block of stone, warm grey to look on with veins of a lighter hue here and there, and here and there a shimmer as of silver in the texture of the stone; and that stone was dream-stone, a thing beyond price, endowed with hidden virtues. But from behind, uplifted like the wings of a wild-duck as it settles on the water, great wings shadowed the dream-stone; they sprang twenty cubits high from base to the topmost feather, and made all of gold, each particular feather fashioned to the likeness of nature that it was a wonder to look upon, and yet with so much awfulness of beauty and shadowing grace in the grand uprising of the wings as made these small perfections seem but praise and worship of the principal design which gave them their life and which from them took again fulfilment. Thousands of thousands of tiny precious stones of every sort that grows in earth or sea were inlaid upon those mighty wings, incrusting each particular quill, each little barb of each feather, so that to a man moving in that hall and looking upon the wings the glory unceasingly changed, as new commixtures of myriad colours and facets caught and threw back the light. And, for all this splendour, the very light in the throne-room was, by art of Doctor Vandermast, made misty and glamorous: brighter than twilight, gentler than the cold beams of the moon, as if the light itself were resolved into motes of radiance which, instead of darting afar, floated like snow-flakes, invisible themselves but bathing all else with their soft effulgence. For there was in all that spacious throne-room not a shadow seen, nor any sparkle of over-brilliance, only everywhere that veiling glamour.

Twenty-five soldiers of the Duke’s bodyguard were drawn up beside the throne on either hand. Their byrnies and greaves were of black iron, and they were weaponed with ponderous double-edged two-handed swords. Each man carried his helm in the crook of his left arm, for it was unlawful even for a man-at-arms to appear covered in that hall: none might so appear, save the Duke alone. They were all picked men for strength and stature and fierceness; the head of every man of them was shaven smooth like an egg, and every man had a beard, chestnut-red, that reached to his girdle. Save these soldiers only, the company came not beyond the fair carpet’s edge that went the width of the hall before the throne; for this was the law in Zayana, that whosoever, unbidden of the Duke, should set foot upon that carpet should lose nothing but his life.

But in the great spaces of the hall below the carpet was such a company of noble persons walking and discoursing as any wise man should take pure joy to look upon: great states of Meszria all in holiday attire; gentlemen of the Duke’s household, and of Memison; courtmen and captains out of Fingiswold holden to the lord Admiral’s service or the Chancellor’s or Earl Roder’s, that triple pillar of the great King’s power in the south there, whereby he had in his life-days and by his politic governance not so much held down faction and discontents as not suffered them be thought on or take life or being. But now, King Mezentius dead, his lawful son sudden where he should be wary, fumbling where he should be resolute; his bastard slighted and set aside and likely (in common opinion) to snatch vengeance for it in some unimagined violence; and last, his Vicar in the midland parts puffed up like a deadly adder ready to strike, but at whom first none can say: these inconveniences shook the royal power in Meszria, patently, for even a careless eye to note, even here in Duke Barganax’s presence-chamber.

A bevy of young lords of Meszria, standing apart under the perfume tripod in the south-eastern corner whence they might at leisure view all that came in by the great main doors at the southern end, held light converse. Said one of them, ‘Here comes my lord Admiral.’

‘Ay,’ said another, ‘main means of our lingering consumption: would the earth might gape for him.’

‘Nay,’ said a third, that was Melates of Vashtola, ‘I do love my Jeronimy as I love a young spring sallet: cold and safe. I will not have you blame him. Do but look: as puzzled as a cod-fish! For fancy’s passion, spit upon him. Nay, Roder and Beroald are the prime blood-suckers, not he.’

‘Speak lower,’ said the Lord Barrian, he that spoke first; ‘there’s jealous ears pricked all-wheres.’

With a grave salutation they greeted the High Admiral, who with a formal bow passed on. He was somewhat heavy of build, entered a little into the decline of years; his pale hair lay lankish on the dome of his head, his pale blue eyes were straight and honest; the growth of his beard was thin, straggling over the great collar and badge of the kingly order of the hippogriff that he wore about his neck; the whole aspect of the man melancholy, and as if strained with half-framed resolutions and wishes that give the wall to fears. Yet was the man of a presence that went beyond his stature, which was but ordinary; as if there hung upon him some majesty of the King’s power he wielded, of sufficiency (at least in trained and loyal soldiery under arms) to have made a fair adventure to unseat the Duke upon Acrozayana, red-bearded bodyguard and all.

When he was passed by, Zapheles spake again, he that had spoken second: ‘Perfidiousness is a common waiter in most princes’ courts. And so, in your ear, were’t not for loyal obligement to a better man, I’d call it time to serve, though late, our own interest: call in him you wot of: do him obedience, ’stead of these plaguish stewards and palace-scullions that, contrary to good cupping-glasses, must affect and suck none but the best blood.’

Melates looked warily round, ‘I taught you that, my lord: ’tis a fine toy, but in sober sadness I am not capable of it. Nor you neither, I think.’