Полная версия

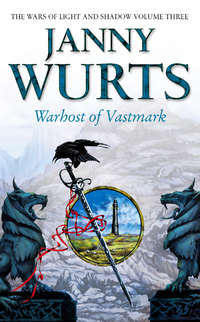

Warhost of Vastmark

‘Your tactics have only burned away the dross,’ Dakar pressured as Arithon turned the sloop’s second anchor line on a cleat and flipped in a sailor’s half hitch. ‘You now face the eastlands’ most gifted commanders. They won’t make misjudgments for the season and the supply lines. They’ll know to the second how long they can expect prime performance from an army in foreign territory.’

Dakar fiddled with his cuff laces, a half-moon smile of anticipation masked behind his moustache. Against established officers and hard-bitten veterans, the livestock raids made by Selkwood’s barbarians would gad this war host no worse than stings by a handful of hornets.

‘In case you hadn’t noticed, Erlien’s clansmen dance to their own mad tune.’ Arithon straightened and wiped salty hands on his breeches. ‘Am I meant to be grateful for your wisdom as a war counsellor? Lysaer and the duke won’t find much satisfaction using crack mercenaries to beat the empty brush at Scimlade Tip.’

Too wily now to rise to goading, Dakar listened and caught the fleeting catch of pain that even a masterbard’s skill could not quite pass off as insouciance. Merior’s abandonment to the whim of hostile forces stung, and surprisingly deeply. Just what the village had meant to Arithon, Dakar avowed to find out.

Asandir’s geas bound his person to the Shadow Master’s footsteps. Unless he wished to be crushed like furniture in the thrust of Lysaer’s campaign, he must sound Arithon’s plans, then use whatever vulnerable opening he could find to leverage influence over their paired fate.

But his nemesis acted first in that maddening, wayward abandon that seemed designed to whip Dakar to fury.

Given the intent to embark on a foray into the mountains of Vastmark, the Mad Prophet blinked, caught aback. ‘Ath, whatever for? There’s naught in these hills at this season but frost-killed bracken and starving hawks. The shale beds in the heights get soaked in the rains, and the rockslides can mill you to slivers. Those shepherds with sense will have driven their flocks to the lowest valleys until well after the first spring thaw.’

For answer, Arithon packed a small satchel with necessities. He heated his horn recurve bow over the galley stove to soften the laminate enough to string. Then he fetched his lyranthe, his hunting knife and sword, and piled them into the dory.

‘You’ll need warmer clothing,’ Dakar said in tart recognition that the shore excursion lay beyond argument. His dissent was ongoing as he squeezed his girth past the chart desk to delve in a locker and scrounge out a pair of hose without holes. ‘There’s ice on the peaks. How long are you planning to sulk in the hills if it’s snowing?’

‘If you wish warm clothes, fetch them.’ Arithon checked the sloop’s anchor lines one final time, then climbed the rail and dropped into his rocking tender. The yard workers I’ve retained won’t rejoin us here for at least another two fortnights. If you stay, the wait could be lonely. I didn’t provision to live aboard.’

Dakar almost lost his temper. No hunter by choice, he detested the stringy taste of winter game. Just how the Shadow Master proposed to maintain his team of experienced shipwrights lay beyond reason since the coffers from Maenalle were empty. Whatever else drew him to peruse the barren uplands that sliced like broken razors against the clouds, the principality of Vastmark was by lengths the loneliest sweep of landscape on the continent. The shepherds who wrested their livelihood from its wind-raked, boggy corries subsisted in wretched poverty.

In distrust and suspicion that Arithon’s excursion must be plotted as a feint to mask a more devious machination, the Mad Prophet snatched up his least-battered woollens, crammed them in a wad in his cloak, and in a clumsy boarding that rocked water over a gunwale, parked his bulk in the stern of the tender.

His compliance did not extend to shouldering the work of an oar. Nor when the craft beached on the nar row, pebbled strand did he lift a finger to help drag the dory into cover above the high tide mark. Ferret insight into Arithon’s affairs though he might through adventure into a wilderness, Dakar scowled to express his commensurate distaste. Open-air treks and clambering up scarps like a goat came second only to the mazes through sand grains once dealt him as punishment by Asandir.

The pace Arithon set in ascent from the strand was brutal enough to wring oaths from a seasoned mercenary. Breathless within minutes, aching tired inside an hour, Dakar toiled over rock that slipped loose beneath his boot soles, and wormed past chiselled escarpments which abraded the soft skin of his hands. The wind poured in cold gusts off the heights, freighted with the keen snap of frost. Chilled in his sweat-sodden woollens, raked over by gorse spines, and sliced on both palms from grasping dried bracken to stay upright, Dakar hung at Arithon’s heels in an unprecedented, stalwart forbearance. The higher the ascent, the more stoic he became, until exhaustion sapped even his penchant for cursing.

By then, the divide of the Kelhorn Mountains loomed in saw-toothed splendour above; below and to the northwest, in valleys the sheenless brown of crumpled burlap, the black- and red-banded stone of a ruin snagged through the crowns of the hills. Once a Paravian stronghold, the crumbled remains of a power focus threw a soft, round ring through the weeds that overran the site. Had Arithon not lost access to the talent that sourced his mage training, he would have seen the faint flicker of captured power as the fourth lane’s current played through the half-buried patterns. Since the site of Second Age mysteries posed the most likely reason for today’s journey, Dakar’s outside hope became dashed as the valley was abandoned for a stonier byway which scored a tangled track to the heights.

Once into the rough footing of the shale slopes, Arithon left the trail to dig for rootstock. He offered no conversation. The Mad Prophet spent the interval perched atop an inhospitable rock, undignified and panting.

The afternoon dimmed into cloudy twilight. Arithon strung his bow and shot a winter-thin hare, which Dakar cooked in inimical silence over a tiny fire nursed out of sticks and dead brush. Vastmark slopes were too wind-raked for trees, the gravelly soil too meagre to anchor even the stunted firs that seized hold at hostile sites elsewhere. The only crannies not scoured bare by harsh gales lay swathed in prickly furze. A man without blankets must bed down on rock, wrapped in a cloak against the cold, or else perish from lack of sleep, spiked at each turn by vegetation that conspired to itch or prickle.

Dakar passed the night in miserable, long intervals of chilled wakefulness broken by distressed bouts of nightmare. He arose with the dawn, disgruntled and sore, but still entrenched in his resolve to outlast the provocations set by his s’Ffalenn nemesis.

They broke fast on the charred, spitted carcass of a grouse and butterless chunks of ship’s biscuit, then moved on, Dakar in suffering silence despite the grievance of being forced to climb while he still felt starved to the bone. Arithon seemed none the worse for yesterday’s energetic side trips. His step on the narrow rims of the sheep trails stayed light and sure, the bundles slung from his shoulder no impediment to the steepest ascent.

‘You know,’ Dakar gasped in vain attempt to finagle a rest stop, ‘if you slip and fall, you’ll see Elshian’s last lyranthe in this world crunched into a thousand sad splinters.’

Poised at the crest of an abutment, Arithon chose not to answer. Dakar sucked wind to revile him for rudeness, then stopped against his nature to look closer. ‘What’s wrong?’

Arithon shaded his eyes from the filtered glare off the cloud cover and pointed. ‘Do you see them?’

Dakar huffed through his last steps to the ridgetop. His scowl puckered into a squint as he surveyed the swale below their vantage.

The landscape was not empty. Sinister and black above the rim of a dry river gorge, creatures on thin-stretched, membranous wings dipped and soared on the wind currents. The high mountain silence rang to a shrill, stinging threnody of whistles.

‘I thought the great Khadrim were confined to the preserve in Tornir Peaks.’ Prompted by a past encounter that had ended in a narrow escape, Arithon reached tot his sword.

‘You need draw no steel. Those aren’t Khadrim,’ Dakar corrected. ‘They’re wyverns; smaller; less dangerous; non-fire-breathing. If you’re a sheep, or a leg-broken horse, you’ve got trouble in plenty to worry about. The Vastmark territory’s thick with their eyries, but they seldom trouble anything of size.’ He studied the creatures’ wheeling, kite-tailed flight a considered moment longer. ‘Those are onto something, though. Wyverns don’t pack up without reason.’

‘Shall we see what they’re after?’ When his footsore companion groaned in response, Arithon grinned and leaped off the boulders to land running through the gorse down the ridge.

‘It’s likely just the carcass of a mountain cat,’ Dakar carped. ‘Mother of all bastards, will you slow down? You’re going to see me trip and break my neck!’

Arithon called over his shoulder, cheerful. ‘Do that and you’ll just have to roll your fat self off this mountainside. No trees grow within a hundred and fifty leagues to cut any poles to make a litter.’

Ripped by a bilious stab of hatred, Dakar spat an epithet on each tearing breath until he slipped and bit his tongue between syllables. Sullen and sickened by the rank taste of blood, he hauled up panting beside the Master of Shadow and gazed over the brim of the cliff head.

The first minute, his eyes refused to focus. His head swam, and not from the pain; sharp drops from great heights infallibly made him unwell. Where the wyverns ducked and wove in fixed interest, the channel-worn rock delved out by a glacial stream slashed downward into a ravine. The bottom lay dank as a pit. More wyverns threaded through the depths. Their dark scales glinted blue as new steel, and their spiked wingtips knifed a whine like a sabre cut through updraughts and invisibly roiled air.

Arithon paused a scant second, then stooped and slung off his lyranthe.

‘You’re not going down there,’ Dakar objected.

He received a look the very palest of chill greens that boded the worst sort of obstinacy. ‘Would you stop me?’ Arithon said.

‘Ath, no.’ Dakar gestured toward the defile. ‘Be my guest. You’re most welcome to crash headlong to your death. I’ll stay here and applaud while the wyverns gnaw the bones of your carcass.’

Arithon stooped, caught a handhold, and dropped down onto a broken, narrow ledge. There he must have found a goat track. His black head blended with the shadow in the cleft. Dakar resisted the suicidal, mad urge to drive him back by threatening to hurl Halliron’s instrument after him into the abyss. In the cold-hearted hope he might witness his enemy’s fall instead, the Mad Prophet tightened his belt to brace the quiver in his gut, grabbed a furze tuft for security, and skidded downslope on his fundament.

The wyverns cruising like nightmare shuttlecocks screamed in piercing outrage, then flapped wings and arrowed up from the cleft. From what seemed a secure stance on an outcrop below, Arithon kicked a spray of gravel into the ravine. The pebbles bounced, cracking, from stone to stone in plunging arcs, and startled four other settled monsters into flight. The chilling, stuttered whistles they shrilled in alarm raised a dissonance to ache living bone marrow.

Dakar saw Arithon suddenly drop flat on his belly. He peered downward also, unable to gain vantage into the recess beneath the moss-rotten underhang. The Shadow Master’s exclamation of warning came muffled behind a sleeve as he rolled, unlimbered his strung bow from his shoulder, then positioned himself on one knee and nocked an arrow.

Moved by danger to scramble and close the last descent, Dakar also spotted the quarry which held the wyverns in circling patterns.

In the deep shade of a fissure, on a ledge lower down, a shepherd in a stained saffron jerkin crouched braced at bay against the cliff face. One arm was muffled in a dusty dun cloak. The streaked fingers of his other hand were glued to the haft of a bloodied dagger. Heaped to one side like a sun-shrivelled hide, the corpse of a wyvern lay draped on the scarp. The gouged socket of the eye that took the death wound tipped skyward, stranded in gore like a girl’s discarded ribbons between the needle teeth that rimmed the parted, horny scales of its jaw.

Another living wyvern perched just beyond weapon’s reach, wings half-furled and its snake-slender neck cocked to snap. Its golden, round eye shone lambent in the gloom, fixed on the steel which was all that deterred its killing strike.

Arithon drew his horn recurve. The arrow he fired hissed down in angled aim and took the predator just behind the foreleg.

The wyvern squalled in mortal pain. Its finned tail lashed against the rocks. Torn vegetation and a bashed fall of stones clattered down the ravine. The leathery crack as its pinions snapped taut buffeted a gusty snap of air. One taloned hind limb raised to claw the shaft, then spasmed, contorted into death throes. The creature overbalanced. It battered backward and plummeted off the vertical rock wall to a thrash of scraped scales and torn wings.

The man with the knife jerked his chin up, his face a pale blur against the gloom. He cried in hoarse fear as another wyvern plunged from its glide in a screaming, wrathful stoop, talons outstretched to slash and tear whatever moved in the open.

Arithon nocked and drew a second arrow. ‘I thought you said they never fought in packs!’

‘They don’t.’ Morbidly riveted, Dakar watched the weapon tip track its descending target, the twang of release left too late to forgive a missed shot. Arithon’s shaft sang out point-blank and smacked home. The wyvern wrenched out of its plunge. It cartwheeled, the arrow buried to the fletching beneath its wing socket.

His envy compounded with unabashed regret for such nerveless, exacting marksmanship, Dakar qualified. ‘That was the mate of the one you killed first. The creatures fly paired. They defend their own to the death.’

‘I believe you.’ The edged look of temper Arithon threw back bruised for its knowing, poisoned irony. ‘But if you happen to be wrong, you’d better do the same.’ He thrust his bow and his unhooked quiver into the Mad Prophet’s startled grasp.

Unable to mask his raised hackles, Dakar glared as Arithon hurled himself over the lip of the ledge. ‘You think I’d bother? I don’t care how often you’re reminded. It’s no secret I’ll rejoice to see you dead.’

Arithon’s reply slapped back in hollow echoes off the sheer walls of the ravine. ‘I’m not quite the fool I appear. With eighty leagues of mountains between here and Forthmark, if you don’t fancy climbing, you’re stuck. Unless you find the sea legs to single-hand my sloop.’

‘That’s not funny.’ Dakar cast down bow and arrows in disgust and sucked in his paunch to give chase. If his descent was ungraceful, he was scarcely less fast. He dropped to the lower ledge in a shower of dragged gravel, yanked down the tunic left hiked up to his armpits, then spat out the inhaled ends of his beard to deliver a scathing retort.

His words died unspoken. A shudder of horror swept through him as he saw: the shepherd with the knife proved no man at all, but a boy not a year more than twelve.

The child stared at his rescuers in uncomprehending shock, eyes dark and round in a face of vivid angles, drained to wax pallor beneath its scuffed dirt. Straw tails of hair stuck in matted hanks to a bloodied shoulder. The stained, cloak-wrapped wrist used to fend off teeth and talons was rust with the same stiffened stains. His shirt was more red than saffron. The one bare foot visible beneath the ripped cuff of his trouser lay swollen beyond recognition.

‘Daelion forfend, you’re a very lucky boy to be alive,’ Dakar said. Overhead, the wyvern pack whistled and dived in balked circles, too wary to close now their prey was defended.

While Dakar battled to contain squeamish nerves, Arithon bent, caught the child’s knife wrist, and pried his sticky fingers off the grip. ‘It’s all right. Help has come. You aren’t going to need that any more.’

The boy broke with a shuddering whimper. Arithon bundled his head against his chest and cradled him tightly, then used his left hand to probe the hot, swollen flesh above the ankle. The child flung back against his hold as he touched. ‘Easy. Easy. We’ll have you up out of here in just a minute.’ But the jagged grate of bone underneath his light fingers belied his banal reassurance.

As if crazed by pain, the boy struggled desperately harder.

‘Jilieth,’ he gasped, the first clear word he had spoken. ‘Look to Jilie.’ He fought an arm free to tug at something shielded in the crevice behind his back: a second, more heartrending bundle splashed in scarlet.

‘Merciful Ath!’ Dakar dropped to his knees, his antipathy eclipsed. Closer inspection showed a face and a small hand inside the mass of shredded clothing. Behind the boy lay a second child, a girl no more than six.

‘Your sister?’ asked Arithon.

The boy gave a stricken nod.

‘All right then, be brave.’ While the Shadow Master shifted the injured boy aside, Dakar squeezed past with tender care and lifted the younger girl’s pitiful, torn body into the open. She stirred awake at his touch. The one eye she had left fixed, brown and beseeching, on his bearded, stranger’s face. ‘Papa. Where’s my papa?’

The Mad Prophet clenched his jaw in helpless grief. ‘If I could command even half of what Asandir taught me, I could help.’

‘Never mind that.’ Arithon loosed the boy with a murmur of encouragement, turned aside, and cupped the girl’s tear-streaked face.

‘Papa,’ she repeated as his shadow crossed over her.

‘Your father is with you, believe it,’ he assured in the schooled, steady timbre earned in study for his masterbard’s title.

‘Ghedair said he would come.’ The girl gasped. Blood welled and trickled from the corner of her mouth. Her chest heaved against drowning congestion as she forced in another pained breath. ‘It hurts. Tell my papa, it hurts.’

Arithon soothed back crusted hair to bare the mauled ruin a wyvern had left when its front talons had raked and grasped her face. The rear claw had sunk through her shoulder and chest; deep gashes had torn when it flew. Ends of separated bone and ripped cartilage showed blue through the shreds of her blouse.

It wasn’t Ghedair’s fault,’ the girl blurted. ‘He was watching. But I ran off. Then wyverns came.’

‘Hush.’ Arithon added a phrase in lilted Paravian, too low for Dakar to translate. But the powerful ring of compassion in his tone could have drawn out the frost from ice itself. ‘I know that, Jilieth. Stop fretting.’

In merciful relief, the child’s one eye slid closed.

‘Your bard’s gift let her sleep?’ the Mad Prophet asked.

Arithon soothed her cheek against Dakar’s rough clad shoulder. ‘That’s the best I could do.’ In the moment he glanced up, the deep empathy of his feelings stripped his face beyond hope of concealment. ‘Keep her quiet if you can.’

Stupid with shock, Dakar clung to the girlchild while the Shadow Master bent to tend the boy. The blood on the torn saffron jerkin proved more the dead wyvern’s or his sister’s than his own. The arm, bundled out of its swathe of shredded cloak, bore deep punctures and gashes swollen to angry red. The break above the ankle was clean beneath the swelling. Arithon patted the boy’s crown, arose, and in a fit of balked grace, kicked the rank, knife-hacked corpse of the other fallen wyvern over the edge of the outcrop. The implication was enough to stop thought, that somewhere lay another slain mate.

The resourceful boy owned courage enough to shame a full-grown man.

While the rest of the drake pack, in a squalling, stabbing squabble, glided down the gorge to scavenge the remains of their dead, Arithon disrupted Dakar’s appalled stupor in brisk and fluent Paravian. ‘We’ll have to splint the leg first. Arrow shafts should do for the purpose. I’ll tie them with my cuff lacings. The girl, we’ll have to bind up as we may. I hate the delay, yet we’ve got no choice. They’ll have to be moved. The herbs in my satchel and some of the roots can be pounded up to make poultices. But I can’t brew the remedies without water and sheltered ground to make a fire.’

‘There ought to be springs at the base of the cliffs,’ Dakar said.

‘Then we’ll find a path down.’ A leap and an athletic slither saw Arithon up to the ridgetop. He returned with his quiver and spare shirt. Before need that disallowed the indulgence of his hatreds, Dakar lent his hands to the grim work of splinting and binding.

The boy gave one full-throated, agonized cry as his shinbone was pulled into line and set straight. Arithon spoke to him, soothingly gentle, a constant barrage of reassurance. Whether his voice spun fine magic, or cruel pain claimed its due, when the ankle and knee were strapped immobile, the child lay quiet, unconscious.

‘Pity them both,’ Dakar whispered as he ripped linen to strap Jilieth’s gaping lacerations. ‘She must be half-empty of blood.’ He need not belabour his certainty that the wounds beneath his hands were surely mortal. The grief in the Shadow Master’s expression matched him in stricken understanding.

‘There’s hope. We might save her,’ Arithon insisted as he tucked the shepherd boy into the folds of his cloak.

Dakar pushed back upright and trailed through the climb up the cliff path, the girl cradled limp in his arms. ‘Are you mad? Five bones in her rib cage are separated from the cartilage, and one lung is filled up with blood!’

‘I know.’ Arithon draped the boy over his shoulders, clasped the small, unmarked wrist and one ankle, then set his weight to scale the last rise of rock. ‘Just keep her alive until we find a spring. If she’s still breathing then, try and find the forbearance to trust me.’

Dakar clamped his teeth. The Prince of Rathain had never asked his help; never before now bent his stiff royal pride to admit that other company was better than a burden to be managed in blistering tolerance. If Asandir’s geas hounded Dakar to sheer misery, for Arithon, the bonding was a nuisance.

Tempted into a sympathy that felt like self-betrayal, Dakar ground out the first rude word to cross his mind. Then, stubborn in prosaic disbelief, he passed the doomed girl into Arithon’s waiting grip and dragged his plump carcass back up the rim wall to the slope.

Two hours later, on a sandy bank beside a rock pool, Arithon prepared a heated poultice to treat the punctures and slashes on Ghedair’s mauled forearm. His concentration seemed unaffected by the oppressive gloom of the site. Damp and streamered in green shags of moss, the gorge reared up sheer on two sides, the sky a hemmed ribbon between. Light seeped through the clouds, dim as the gleam off a miser’s silver, while the breeze fluted mournfully through the defiles. Far off, the braided whistles of a wyvern pair screeled in bone-chilling dissonance.

Tired of feeling useless, set on edge by the spring’s erratic plink of seeped droplets, Dakar gave rein to spite and prodded Arithon to elaborate on his earlier, misguided cause for hope.

‘Jilieth’s already failing.’ The clogged drag of her chest seemed to worsen with each tortured breath that she drew. To distance the unaccustomed sting of pity, the Mad Prophet lashed out. ‘You know full well there’s nothing left to do but keep her warm and sheltered until she dies.’

Her face by then had been cleansed and swathed in the torn strips from Arithon’s spare shirt. Outside the bandaging, the lashes of her undamaged eye remained, fanned like cut ends of silk against a cheek so colourless the freckles shone dull grey. To look at her at all, to see her child’s hands so far removed from life they never twitched, was to suffer a sorrow past endurance.