Полная версия

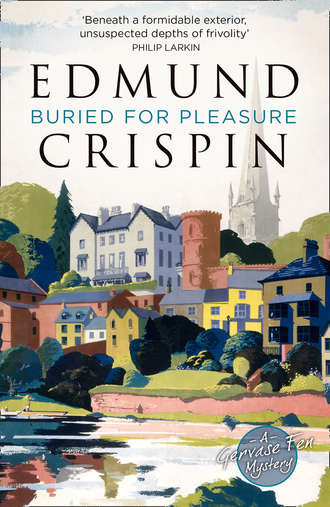

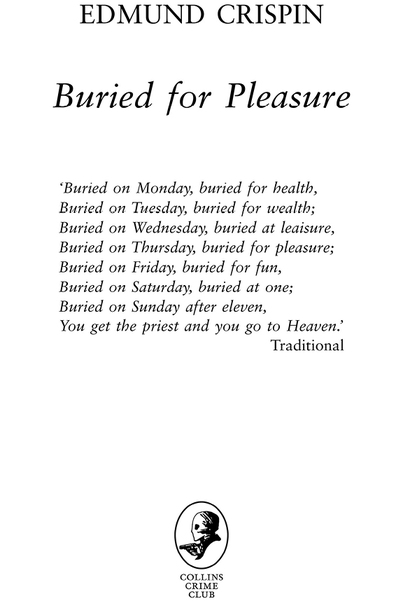

Buried for Pleasure

Copyright

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Victor Gollancz 1948

Copyright © Rights Limited 1948

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Edmund Crispin asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it

are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead,

events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive,

non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled,

reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and

retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical,

now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008228064

Ebook Edition © March 2018 ISBN: 9780008228071

Version: 2018-01-02

Dedication

For Peter Oldham

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

About the Author

Also in this Series

About the Publisher

Chapter One

‘Sanford Angelorum all change,’ said the station-master. ‘Sanford Angelorum, all change.’

After a moment’s thought: ‘Terminus,’ he added, and retired from the scene through a door marked PRIVATE.

Gervase Fen, dozing alone in a narrow, stuffy compartment whose cushions, when stirred, emitted a haze of black dust, woke and roused himself.

He peered out of the window into the summer twilight. A stunted, uneven platform offered itself to his inspection, its further margins cluttered with weed-like growths which a charitable man might have interpreted as attempts at horticulture. An empty chocolate-machine lay rusting and overturned, like a casualty in some robot war. Near it was a packing-case from which the head of a small chicken protruded, uttering low, indignant squawks. But there was no trace of human kind, and beyond the station lay nothing more companionable than an apparently limitless expanse of fields and woods, bluish in the gathering dusk.

This panorama displeased Fen; he thought it blank and unenlivening. There was, however, nothing to be done about it except repine. He repined briefly and then extracted himself and his luggage from the compartment. It seemed at first that he was the only passenger to alight here, but a moment later he found that this was not so, for a fair-haired, neatly-dressed girl of about twenty emerged from another compartment, glanced uncertainly about her, and then made for the exit, where she dropped a square of green pasteboard into a tin labelled TICKETS and disappeared. Leaving his luggage where it lay on the platform, Fen followed.

But the station-yard – an ill-defined patch of gravel – was empty of conveyances; and except for the retreating footsteps of the girl, who had vanished from sight round a bend in the station approach, a disheartening quietude prevailed. Fen went back to the platform and sought out the station-master’s room, where he found the station-master sitting at a table and sombrely contemplating a small, unopened bottle of beer. He looked up resignedly at the interruption.

‘Is there any chance of my getting a taxi?’ Fen asked.

‘Where are you for, sir?’

‘Sanford Angelorum village. The Fish Inn.’

‘Well, you might be lucky,’ the station-master admitted. ‘I’ll see what I can do.’

He went to a telephone and discoursed into it. Fen watched from the doorway. Behind him, the train on which he had arrived gave a weak, asthmatic whistle, and began to back away. Presently it had disappeared, empty, in the direction whence it came.

The station-master finished his conversation and lumbered back to his chair.

‘That’ll be all right, sir,’ he said; and his tone was slightly complacent, as of a midwife relating the successful issue of a troublesome confinement. ‘Car’ll be here in ten minutes.’

Fen thanked him, gave him a shilling, and left him still staring at the beer. It occurred to Fen that perhaps he had taken the pledge and was brooding nostalgically over forbidden delights.

The chicken had got its head out of a particularly narrow aperture of the packing-case and was unable to get it in again; it was bewilderingly eyeing a newish election poster, with an unprepossessing photograph, which said: ‘A Vote for Strode is a Vote for Prosperity.’ The train had passed beyond earshot; a colony of rooks was flying home for the night, dark blurs against a grey sky; flickering indistinctly, a bat pursued its evening meal up and down the line. Fen sat down on a suitcase and waited. He had finished one cigarette, and was on the point of lighting another, when the sound of a car-engine stirred him into activity. He returned, burdened with cases, to the station-yard.

Against all probability, the taxi was new and comfortable; and its driver, too, was unexpectedly attractive – a slim, comely, black-haired young woman wearing blue slacks and a blue sweater.

‘Sorry to keep you waiting,’ she said pleasantly. ‘I occasionally meet this train on the off-chance that someone will want a car, but there are evenings when no one’s on it at all, so it’s scarcely worth while … Here, let me give you a hand with your bags.’

The luggage was stowed away. Fen asked and obtained permission to sit in front. They set off. In the deepening darkness there was little outside the car to repay attention, and Fen looked instead at his companion, admiring what the dashboard light showed of her large green eyes, her full mouth, her fine and lustrous hair.

‘Girls who drive taxis,’ he ventured, ‘are surely uncommon?’

She took her eyes momentarily from the road to glance at him; saw a tall, lean man with a ruddy, cheerful, clean-shaven face and brown hair which stood up mutinously in spikes at the crown of his head. In particular, she liked his eyes; they showed charity and understanding as well as a taste for mischief.

‘Yes, I suppose they are,’ she agreed. ‘But it isn’t at all a bad life if you actually own your car, as I do. It’s been a good investment.’

‘You’ve always done this, then?’

‘No. For a time I worked in Boots – the book department. But it didn’t suit me, for some reason. I used to get dizzy spells.’

‘Inevitable, I should think, if you work in a circulating library.’

A fallen tree appeared out of the gloom ahead of them: it lay half across the lane. The girl swore mildly, braked, and circumnavigated it with care.

‘I always forget that damned thing’s there,’ she said. ‘It was blown down in a gale, and Shooter ought to have taken it away days ago. It’s his tree, so it’s his responsibility. But he’s really intolerably lax.’ She accelerated again, asking: ‘Have you been in this part of the world before?’

‘Never,’ said Fen. ‘It seems very out-of-the-way,’ he added reprovingly. His preferences were not bucolic.

‘You’re staying at the Fish Inn?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, I ought perhaps to warn you—’ The girl checked herself. ‘No, never mind.’

‘What’s all this?’ Fen demanded uneasily. ‘What were you going to say?’

‘It was nothing … How long are you here for?’

‘It can’t have been nothing.’

‘Well, anyway, there’s nowhere else for you to stay, even if you wanted to.’

‘But shall I want to?’

‘Yes. No. That’s to say, it’s an extremely nice pub, only … Oh, damn it, you’ll have to see for yourself. How long are you staying?’

Since it was clear that no further enlightenment was to be expected, Fen answered the question. ‘Till after polling day,’ he said.

‘Oh!… You’re not Gervase Fen, are you?’

‘Yes.’

She glanced at him with curiosity. ‘Yes, I might have known …’

After a pause she went on:

‘You’re rather late starting your election campaign, you know. There’s only a week to go, and I haven’t seen a single leaflet about you, or a poster, or anything.’

‘My agent,’ said Fen, ‘is dealing with all that.’

The girl considered this reply in silence.

‘Look here,’ she said, ‘you’re a Professor at Oxford, aren’t you?’

‘Of English.’

‘Well, what on earth … I mean, why are you standing for Parliament? What put the idea into your head?’

Even to himself Fen’s actions were sometimes unaccountable, and he could think of no very convincing reply.

‘It is my wish,’ he said sanctimoniously, ‘to serve the community.’

The girl eyed him dubiously.

‘Or at least,’ he amended, ‘that is one of my motives. Besides, I felt I was getting far too restricted in my interests. Have you ever produced a definitive edition of Langland?’

‘Of course not,’ she said crossly.

‘I have. I’ve just finished producing one. It has queer psychological effects. You begin to wonder if you’re mad. And the only remedy for that is a complete change of occupation.’

‘What it amounts to is that you haven’t any serious interest in politics at all,’ the girl said with unexpected severity.

‘Well, no, I wouldn’t say that,’ Fen answered defensively. ‘My idea, after I’ve been elected—’

But she shook her head. ‘You won’t be elected, you know.’

‘Why not?’

‘This is a safe Conservative seat. You won’t get a look in.’

‘We shall see.’

‘You may confuse the issue a little, but you can’t affect it ultimately.’

‘We shall see.’

‘In fact, you’ll be lucky if you don’t lose your deposit. What exactly is your platform?’

Fen’s confidence waned slightly. ‘Oh, prosperity,’ he said vaguely, ‘and exports and freedom and that kind of thing. Will you vote for me?’

‘I haven’t got a vote – too young. And anyway, I’m canvassing for the Conservatives.’

‘Oh, dear,’ said Fen.

They fell silent. Trees and coppices loomed momentarily out of the darkness and were swept away again as though by a giant hand. The headlights gleamed on small flowers sleeping beneath the hedges, and the air of that incomparable summer washed in a warm tide through the open windows. Rabbits, their white scuts bobbing feverishly, fled away to shelter in deep, consoling burrows. And now the lane sloped gently downwards; ahead of them they could glimpse, for the first time, the scattered lights of the village…

With one savage thrust the girl drove the foot-brake down against the boards. The car slewed, flinging them forward, then skidded, and at last came safely to a halt. And in the glare of its headlights a human form appeared.

They blinked at it, unable to believe their eyes. It blinked back at them, to all appearance hardly less perturbed than they. Then it waved its arms, uttered a bizarre piping sound, and rushed to the hedge, where it forced its way painfully through a small gap and in another moment, bleeding from a profusion of scratches, was lost from view.

Fen stared after it. ‘Am I dreaming?’ he demanded.

‘No, of course not. I saw it, too.’

‘A man – quite a large, young man?’

‘Yes.’

‘In pince-nez?’

‘Yes.’

‘And with no clothes on at all?’

‘Yes.’

‘It seems a little odd,’ said Fen with restraint.

But the girl had been pondering, and now her initial perplexity gave way to comprehension. ‘I know what it was,’ she said. ‘It was an escaped lunatic.’

This explanation struck Fen as conventional, and he said as much.

‘No, no,’ she went on, ‘the point is that there actually is a lunatic asylum near here, at Sanford Hall.’

‘On the other hand, it might have been someone who’d been bathing and had his clothes stolen.’

‘There’s nowhere you can bathe on this side of the village. Besides, I could see that his hair wasn’t wet. And didn’t he look mad to you?’

‘Yes,’ said Fen without hesitation, ‘he did. I suppose,’ he added unenthusiastically, ‘that I ought really to get out and chase after him.’

‘He’ll be miles away by now. No, we’ll tell Sly – that’s our constable – when we get to the village, and that’s about all we can do.’

So they drove on, preoccupied, into Sanford Angelorum, and presently came to ‘The Fish Inn’.

Chapter Two

Architecturally, ‘The Fish Inn’ did not seem particularly enterprising.

It was a fairly large cube of grey stone, pierced symmetrically by narrow, mean-looking doors and windows, and surrounded by mysterious, indistinguishable heaps of what might be building materials. Its signboard, visible now in the light which filtered from the curtained windows of the bar, depicted murky subaqueous depths set about with sinuous water-weed; against this background a silvery, generalized marine creature, sideways on, was staring impassively at something off the edge of the board.

From within the building, as Fen’s taxi drew up at the door, there issued noises suggestive of agitation, and periodically dominated by a vibrant feminine voice.

‘It sounds to me as if they’ve heard about the lunatic,’ said the girl. ‘I’ll come in with you, in case Sly’s there.’

The inn proved to be more prepossessing inside than out. There was only one bar – the tiresome distinction of ‘lounge’ and ‘public’ having been so far excluded – but it was roomy and spacious, extending half the length and almost all the width of the house. The oak panelling, transferred evidently from some much older building, was carved in the linenfold pattern; faded but still cheerful chintz curtains covered the windows; a heavy beam traversed the ceiling; oak chairs and settles had their discomfort partially mitigated by flat cushions. The decoration consisted largely of indifferent nineteenth-century hunting prints, representing stuffed-looking gentlemen on the backs of fantastically long and emaciated horses; but in addition to these there was, over the fireplace, a canvas so large as to constitute something of a pièce de résistance.

It was a seascape, which showed, in the foreground, a narrow strip of shore, up which some men in oilskins were hauling what looked like a primitive lifeboat. To the left was a harbour with a mole, behind which an angry sky suggested the approach of a tornado. And the rest of the available space, which was considerable, was taken up with a stormy sea, flecked with white horses, upon which a number of sailing-ships were proceeding in various directions.

This spirited depiction, Fen was to learn, provided an inexhaustible topic of argument among the habitués of the inn. From the seaman’s point of view, no such scene had ever existed, or could ever exist, on God’s earth. But this possibility did not seem to have occurred to anyone at Sanford Angelorum. It was the faith of the inhabitants that if the artist had painted it thus, it must have been thus. And tortuous and implausible modes of navigation had consequently to be postulated in order to explain what was going on. These, it is true, were generally couched in terms which by speakers and auditors alike were only imperfectly understood; but the average Englishman will no more admit ignorance of seafaring matters than he will admit ignorance of women.

‘No, no; I tell ’ee, that schooner, ’er’s luffin’ on the lee shore.’

‘What about the brig, then? What about the brig?’

‘That’s no brig, Fred, ’er’s a ketch.’

‘’Er wouldn’t be fully rigged, not if ’er was luffing.’

‘Look ’ere, take that direction as north, see, and that means the wind’s nor’-nor’-east.’

‘Then ’ow the ’ell d’you account for that wave breaking over the mole?’

‘That’s a current.’

‘Current, ’e says. Don’t be bloody daft, Bert, ’ow can a wave be a current?’

‘Current. That’s a good one.’

At the moment when Fen first set eyes on this object, however, it had temporarily lost its hold on the interest of the inn’s clients. This was due to the presence of an elderly lady in a ginger wig who, surrounded by a circle of listeners, was sitting in a collapsed posture on a chair, engaged, between sips of brandy, in vehement and imprecise narration.

‘Frightened?’ she was saying. ‘Nearly fell dead in me tracks, I did. There ’e were, all white and nekked, lurking be’ind that clump of gorse by Sweeting’s Farm. And jist as I passes by, out ’e jumps at me and “Boo!” ’e says, “Boo!”’

At this, an oafish youth giggled feebly.

‘And what ’appened then?’ someone demanded.

‘I struck at ’im,’ the elderly lady replied, striking illustratively at the air, ‘with me brolly.’

‘Did you ’it ’im?’

‘No,’ she admitted with evident reluctance. ‘’E slipped away from me reach, and off ’e went before you could say “knife”. And ’ow I staggered ’ere I shall never know, not to me dying day. Yes, thank you, Mrs ’Erbert, I’ll ’ave another, if you please.’

‘’E must ’a’ bin a exhibitor,’ someone volunteered. ‘People as goes about showing thesselves in the altogether is called exhibitors.’

But this information, savouring as it did of intellectual snobbery, failed to provoke much interest. A middle-aged, bovine, nervous-looking man in the uniform of a police constable, who was standing by with a note-book in his hand, said:

‘Well, us all knows what ’tis, I s’pose. ’Tis one o’ they loonies escaped from up at ’all.’

‘These ten years,’ said a gloomy-looking old man, ‘I’ve known that’d ’appen. ’Aven’t I said it, time and time again?’

The disgusted silence with which this rhetorical question was received indicated forcibly that he had; with just such repugnance must Cassandra have been regarded at the fall of Troy, for there is something distinctly irritating about a person with an obsession who turns out in the face of all reason to have been right.

The adept in psychological terminology said: ‘Us ought to organize a search-party, that’s what us ought to do. ’E’m likely dangerous.’

But the constable shook his head. ‘Dr Boysenberry’ll be seeing to that, I reckon. I’ll telephone ’im now, though I’ve no doubt ’e knows all about it already.’ He cleared his throat and spoke more loudly. ‘There is no cause for alarm,’ he announced. ‘No cause for alarm at all.’

The inn’s clients, who had shown not the smallest evidence of such an emotion, received this statement apathetically, with the single exception of the elderly lady in the wig, who by now was slightly contumelious from brandy.

‘Tcha!’ she exclaimed. ‘That’s just like ’ee, Will Sly. An ostrich, that’s what you are, with your ’ead buried in sand. “No cause for alarm,” indeed! If it’d bin you ’e’d jumped out at, you’d not go about saying there was “no cause for alarm”. There ’e were, white and nekked like an evil sperrit…’

Her audience, however, was clearly not anxious for a repetition of the history; it began to disperse, resuming abandoned glasses and tankards. The gloomy-looking old man buttonholed people with complacent iterations of his own foresight. The psychologist embarked on a detailed and scabrous account, in low tones, and to an exclusively male circle, of the habits of exhibitors. And Constable Sly, on the point of commandeering the inn’s telephone, caught the eye of the girl from the taxi for the first time since she and Fen had entered the bar.

‘’Ullo, Miss Diana,’ he said, grinning awkwardly. ‘You’ve ’eard what’s ’appened, I s’pose?’

‘I have, Will,’ said Diana, ‘and I think I may be able to help you a bit.’ She related their encounter with the lunatic.

‘Ah,’ said Sly. ‘That may be very useful, Miss Diana. ’E were making for Sanford Condover, you say?’

‘As far as I could tell, yes.’

‘I will inform Dr Boysenberry of that fact,’ said Sly laboriously. He turned to the woman who was serving behind the bar. ‘All right for I to use phone, Myra?’

‘You can use the phone, my dear,’ Myra Herbert said, ‘if you put tuppence in the box.’ She was a vivacious and attractive Cockney woman in the middle thirties, with black hair, a shrewd but slightly sensual mouth, and green eyes, unusually but beautifully shaped.

‘Official call,’ Sly explained with hauteur.

Myra registered disgust. ‘You and your official ruddy calls,’ she said. ‘My God!’

Sly ignored this and turned away; at which the lunatic’s first victim, becoming suddenly aware of his impending departure, roused herself from an access of lethargy to say:

‘And what about me, Will Sly?’

Sly grew harassed. ‘Well, Mrs ’Ennessy, what about you?’

‘You’re not going to leave me to walk ’ome by meself, I should ’ope.’

‘I’ve already explained to you, Mrs ’Ennessy,’ said Sly with painful dignity, ‘that there is no cause for alarm.’

Mrs Hennessy emitted a shriek of stage laughter.

‘Listen to ’im,’ she adjured Fen, who was contemplating his potential constituents with a hypnotized air: ‘Listen to Mr Knowall Sly!’ Her manner changed abruptly to one of menace. ‘For all you knows, Will Sly, I might be murdered on me own doorstep, and then where’d you be? Eh? Tell me that. And what’s me ’usband pay ’is rates for, that’s what I asks. I got a right to pertection, ’aven’t I? I got—’

‘Now, look ’ere, Mrs ’Ennessy, I’ve me duty to do.’

‘Duty!’ Mrs Hennessy repeated with scorn. ‘’E says’ – and here she again addressed Fen, this time with the air of one imparting a valuable confidence – ‘’e says ’e’s got ’is duty to do … Fat lot of duty you do, Will Sly. What about the time Alf Braddock’s apples was stolen? Eh? What about that? Duty!’

‘Yes, duty,’ said Sly, much aggrieved at this unsportsmanlike allusion. ‘And what’s more, the next time I catch you trying to buy Guinness ’ere out of hours—’

Diana interrupted these indiscretions.

‘It’s all right, Will,’ she said. ‘I’ll take Mrs Hennessy home. It’s not far out of my way.’