Полная версия

Harlequin

BERNARD CORNWELL

Harlequin

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2000

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 2000

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

EPub Edition © 2009 ISBN: 9780007338788

Version: 2018-04-20

HARLEQUIN

is for

Richard and Julie Rutherford-Moore

‘…many deadly battles have been fought, people slaughtered, churches robbed, souls destroyed, young women and virgins deflowered, respectable wives and widows dishonoured; towns, manors and buildings burned, and robberies, cruelties and ambushes committed on the highways. Justice has failed because of these things. The Christian faith has withered and commerce has perished and so many other wickednesses and horrid things have followed from these wars that they cannot be spoken, numbered or written down.’

JEAN II, KING OF FRANCE, 1360

Harlequin, probably derived from the Old French hellequin: a troop of the devil’s horsemen.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

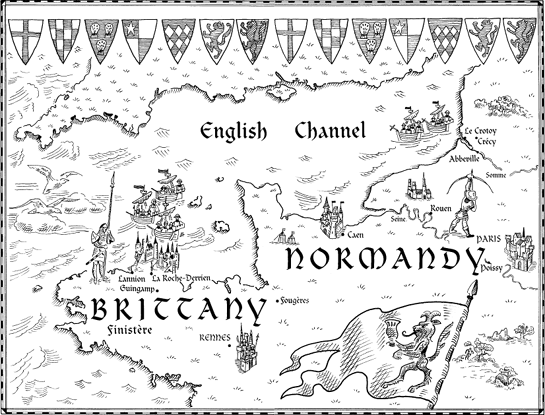

Part One BRITTANY

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Part Two NORMANDY

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Part Three CRÉCY

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Historical Note

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by Bernard Cornwell

About the Publisher

Prologue

The treasure of Hookton was stolen on Easter morning 1342.

It was a holy thing, a relic that hung from the church rafters, and it was extraordinary that so precious an object should have been kept in such an obscure village. Some folk said it had no business being there, that it should have been enshrined in a cathedral or some great abbey, while others, many others, said it was not genuine. Only fools denied that relics were faked. Glib men roamed the byways of England selling yellowed bones that were said to be from the fingers or toes or ribs of the blessed saints, and sometimes the bones were human, though more often they were from pigs or even deer, but still folk bought and prayed to the bones. ‘A man might as well pray to St Guinefort,’ Father Ralph said, then snorted with mocking laughter. ‘They’re praying to ham bones, ham bones! The blessed pig!’

It had been Father Ralph who had brought the treasure to Hookton and he would not hear of it being taken away to a cathedral or abbey, and so for eight years it hung in the small church, gathering dust and growing spider webs that shone silver when the sunlight slanted through the high window of the western tower. Sparrows perched on the treasure and some mornings there were bats hanging from its shaft. It was rarely cleaned and hardly ever brought down, though once in a while Father Ralph would demand that ladders be fetched and the treasure unhooked from its chains and he would pray over it and stroke it. He never boasted of it. Other churches or monasteries, possessing such a prize, would have used it to attract pilgrims, but Father Ralph turned visitors away. ‘It is nothing,’ he would say if a stranger enquired after the relic, ‘a bauble. Nothing.’ He became angry if the visitors persisted. ‘It is nothing, nothing, nothing!’ Father Ralph was a frightening man even when he was not angry, but in his temper he was a wild-haired fiend, and his flaring anger protected the treasure, though Father Ralph himself believed that ignorance was its best protection for if men did not know of it then God would guard it. And so He did, for a time.

Hookton’s obscurity was the treasure’s best protection. The tiny village lay on England’s south coast where the Lipp, a stream that was almost a river, flowed to the sea across a shingle beach. A half-dozen fishing boats worked from the village, protected at night by the Hook itself, which was a tongue of shingle that curved around the Lipp’s last reach, though in the famous storm of 1322 the sea had roared across the Hook and pounded the boats to splinters on the upper beach. The village had never really recovered from that tragedy. Nineteen boats had sailed from the Hook before the storm, but twenty years later only six small craft worked the waves beyond the Lipp’s treacherous bar. The rest of the villagers worked in the saltpans, or else herded sheep and cattle on the hills behind the huddle of thatched huts which clustered about the small stone church where the treasure hung from the blackened beams. That was Hookton, a place of boats, fish, salt and livestock, with green hills behind, ignorance within and the wide sea beyond.

Hookton, like every place in Christendom, held a vigil on the eve of Easter, and in 1342 that solemn duty was performed by five men who watched as Father Ralph consecrated the Easter Sacraments and then laid the bread and wine on the white-draped altar. The wafers were in a simple clay bowl covered with a piece of bleached linen, while the wine was in a silver cup that belonged to Father Ralph. The silver cup was a part of his mystery. He was very tall, pious and much too learned to be a village priest. It was rumoured that he could have been a bishop, but that the devil had persecuted him with bad dreams and it was certain that in the years before he came to Hookton he had been locked in a monastery’s cell because he was possessed by demons. Then, in 1334, the demons had left him and he was sent to Hookton where he terrified the villagers by preaching to the gulls, or pacing the beach weeping for his sins and striking his breast with sharp-edged stones. He howled like a dog when his wickedness weighed too heavily on his conscience, but he also found a kind of peace in the remote village. He built a large house of timber, which he shared with his housekeeper, and he made friends with Sir Giles Marriott, who was the lord of Hookton and lived in a stone hall three miles to the north.

Sir Giles, of course, was a gentleman, and so it seemed was Father Ralph, despite his wild hair and angry voice. He collected books which, after the treasure he had brought to the church, were the greatest marvels in Hookton. Sometimes, when he left his door open, people would just gape at the seventeen books that were bound in leather and piled on a table. Most were in Latin, but a handful were in French, which was Father Ralph’s native tongue. Not the French of France, but Norman French, the language of England’s rulers, and the villagers reckoned their priest must be nobly born, though none dared ask him to his face. They were all too scared of him, but he did his duty by them; he christened them, churched them, married them, heard their confessions, absolved them, scolded them and buried them, but he did not pass the time with them. He walked alone, grim-faced, hair awry and eyes glowering, but the villagers were still proud of him. Most country churches suffered ignorant, pudding-faced priests who were scarce more educated than their parishioners, but, Hookton, in Father Ralph had a proper scholar, too clever to be sociable, perhaps a saint, maybe of noble birth, a self-confessed sinner, probably mad, but undeniably a real priest.

Father Ralph blessed the Sacraments, then warned the five men that Lucifer was abroad on the night before Easter and that the devil wanted nothing so much as to snatch the Holy Sacraments from the altar and so the five men must guard the bread and wine diligently and, for a short time after the priest had left, they dutifully stayed on their knees, gazing at the chalice, which had an armorial badge engraved in its silver flank. The badge showed a mythical beast, a yale, holding a grail, and it was that noble device which suggested to the villagers that Father Ralph was indeed a high-born man who had fallen low through being possessed of devils. The silver chalice seemed to shimmer in the light of two immensely tall candles which would burn through the whole long night. Most villages could not afford proper Easter candles, but Father Ralph purchased two from the monks at Shaftesbury every year and the villagers would sidle into the church to stare at them. But that night, after dark, only the five men saw the tall unwavering flames.

Then John, a fisherman, farted. ‘Reckon that’s ripe enough to keep the old devil away,’ he said, and the other four laughed. Then they all abandoned the chancel steps and sat with their backs against the nave wall. John’s wife had provided a basket of bread, cheese and smoked fish, while Edward, who owned a saltworks on the beach, had brought ale.

In the bigger churches of Christendom knights kept this annual vigil. They knelt in full armour, their surcoats embroidered with prancing lions and stooping hawks and axe heads and spread-wing eagles, and their helmets mounted with feathered crests, but there were no knights in Hookton and only the youngest man, who was called Thomas and who sat slightly apart from the other four, had a weapon. It was an ancient, blunt and slightly rusted sword.

‘You reckon that old blade will scare the devil, Thomas?’ John asked him.

‘My father said I had to bring it,’ Thomas said.

‘What does your father want with a sword?’

‘He throws nothing away, you know that,’ Thomas said, hefting the old weapon. It was heavy, but he lifted it easily; at eighteen, he was tall and immensely strong. He was well liked in Hookton for, despite being the son of the village’s richest man, he was a hard-working boy. He loved nothing better than a day at sea hauling tarred nets that left his hands raw and bleeding. He knew how to sail a boat, had the strength to pull a good oar when the wind failed; he could lay snares, shoot a bow, dig a grave, geld a calf, lay thatch or cut hay all day long. He was a big, bony, black-haired country boy, but God had given him a father who wanted Thomas to rise above common things. He wanted the boy to be a priest, which was why Thomas had just finished his first term at Oxford.

‘What do you do at Oxford, Thomas?’ Edward asked him.

‘Everything I shouldn’t,’ Thomas said. He pushed black hair away from his face that was bony like his father’s. He had very blue eyes, a long jaw, slightly hooded eyes and a swift smile. The girls in the village reckoned him handsome.

‘Do they have girls at Oxford?’ John asked slyly.

‘More than enough,’ Thomas said.

‘Don’t tell your father that,’ Edward said, ‘or he’ll be whipping you again. A good man with a whip, your father.’

‘There’s none better,’ Thomas agreed.

‘He only wants the best for you,’ John said. ‘Can’t blame a man for that.’

Thomas did blame his father. He had always blamed his father. He had fought his father for years, and nothing so raised the anger between them as Thomas’s obsession with bows. His mother’s father had been a bowyer in the Weald, and Thomas had lived with his grandfather until he was nearly ten. Then his father had brought him to Hookton, where he had met Sir Giles Marriott’s huntsman, another man skilled in archery, and the huntsman had become his new tutor. Thomas had made his first bow at eleven, but when his father found the elmwood weapon he had broken it across his knee and used the remnants to thrash his son. ‘You are not a common man,’ his father had shouted, beating the splintered staves on Thomas’s back and head and legs, but neither the words nor the thrashing did any good. And as Thomas’s father was usually preoccupied with other things, Thomas had plenty of time to pursue his obsession.

By fifteen he was as good a bowyer as his grandfather, knowing instinctively how to shape a stave of yew so that the inner belly came from the dense heartwood while the front was made of the springier sapwood, and when the bow was bent the heartwood was always trying to return to the straight and the sapwood was the muscle that made it possible. To Thomas’s quick mind there was something elegant, simple and beautiful about a good bow. Smooth and strong, a good bow was like a girl’s flat belly, and that night, keeping the Easter vigil in Hookton church, Thomas was reminded of Jane, who served in the village’s small alehouse.

John, Edward and the other two men had been speaking of village things: the price of lambs at Dorchester fair, the old fox up on Lipp Hill that had taken a whole flock of geese in one night and the angel who had been seen over the rooftops at Lyme.

‘I reckon they’s been drinking too much,’ Edward said.

‘I sees angels when I drink,’ John said.

‘That be Jane,’ Edward said. ‘Looks like an angel, she does.’

‘Don’t behave like one,’ John said. ‘Lass is pregnant,’ and all four men looked at Thomas, who stared innocently up at the treasure hanging from the rafters. In truth Thomas was frightened that the child was indeed his and terrified of what his father would say when he found out, but he pretended ignorance of Jane’s pregnancy that night. He just looked at the treasure that was half obscured by a fishing net hung up to dry, while the four older men gradually fell asleep. A cold draught flickered the twin candle flames. A dog howled somewhere in the village, and always, never ending, Thomas could hear the sea’s heartbeat as the waves thumped on the shingle then scraped back, paused and thumped again. He listened to the four men snoring and he prayed that his father would never find out about Jane, though that was unlikely for she was pressing Thomas to marry her and he did not know what to do. Maybe, he thought, he should just run away, take Jane and his bow and run, but he felt no certainty and so he just gazed at the relic in the church roof and prayed to its saint for help.

The treasure was a lance. It was a huge thing, with a shaft as thick as a man’s forearm and twice the length of a man’s height and probably made of ash though it was so old no one could really say, and age had bent the blackened shaft out of true, though not by much, and its tip was not an iron or steel blade, but a wedge of tarnished silver which tapered to a bodkin’s point. The shaft did not swell to protect the handgrip, but was smooth like a spear or a goad; indeed the relic looked very like an oversized ox-goad, but no farmer would ever tip an ox-goad with silver. This was a weapon, a lance.

But it was not any old lance. This was the very lance which St George had used to kill the dragon. It was England’s lance, for St George was England’s saint and that made it a very great treasure, even if it did hang in Hookton’s spidery church roof. There were plenty of folk who said it could not have been St George’s lance, but Thomas believed it was and he liked to imagine the dust churned by the hooves of St George’s horse, and the dragon’s breath streaming in hellish flame as the horse reared and the saint drew back the lance. The sunlight, bright as an angel’s wing, would have been flaring about St George’s helmet, and Thomas imagined the dragon’s roar, the thrash of its scale-hooked tail, the horse screaming in terror, and he saw the saint stand in his stirrups before plunging the lance’s silver tip down through the monster’s armoured hide. Straight to the heart the lance went, and the dragon’s squeals would have rung to heaven as it writhed and bled and died. Then the dust would have settled and the dragon’s blood would have crusted on the desert sand, and St George must have hauled the lance free and somehow it ended up in Father Ralph’s possession. But how? The priest would not say. But there it hung, a great dark lance, heavy enough to shatter a dragon’s scales.

So that night Thomas prayed to St George while Jane, the black-haired beauty whose belly was just rounding with her unborn child, slept in the taproom of the alehouse, and Father Ralph cried aloud in his nightmare for fear of the demons that circled in the dark, and the vixens screamed on the hill as the endless waves clawed and sucked at the shingle on the Hook. It was the night before Easter.

Thomas woke to the sound of the village cockerels and saw that the expensive candles had burned down almost to their pewter holders. A grey light filled the window above the white-fronted altar. One day, Father Ralph had promised the village, that window would be a blaze of coloured glass showing St George skewering the dragon with the silver-headed lance, but for now the stone frame was filled with horn panes that turned the air within the church as yellow as urine.

Thomas stood, needing to piss, and the first awful screams sounded from the village.

For Easter had come, Christ was risen and the French were ashore.

The raiders came from Normandy in four boats that had sailed the night’s west wind. Their leader, Sir Guillaume d’Evecque, the Sieur d’Evecque, was a seasoned warrior who had fought the English in Gascony and Flanders, and had twice led raids on England’s southern coast. Both times he had brought his boats safe home with cargoes of wool, silver, livestock and women. He lived in a fine stone house on Caen’s Île St Jean, where he was known as the knight of the sea and of the land. He was thirty years old, broad in the chest, wind-burned and fair-haired, a cheerful, unreflective man who made his living by piracy at sea and knight-service on shore, and now he had come to Hookton.

It was an insignificant place, hardly likely to yield any great reward, but Sir Guillaume had been hired for the task and if he failed at Hookton, if he did not snatch so much as one single poor coin from a villager, he would still make his profit for he had been promised one thousand livres for this expedition. The contract was signed and sealed, and it promised Sir Guillaume the one thousand livres together with any other plunder he could find in Hookton. One hundred livres had already been paid and the rest was in the keeping of Brother Martin in Caen’s Abbaye aux Hommes, and all Sir Guillaume had to do to earn the remaining nine hundred livres was bring his boats to Hookton, take what he wanted, but leave the church’s contents to the man who had offered him such a generous contract. That man now stood beside Sir Guillaume in the leading boat.

He was a young man, not yet thirty, tall and black-haired, who spoke rarely and smiled less. He wore an expensive coat of mail that fell to his knees and over it a surcoat of deep black linen that bore no badge, though Sir Guillaume guessed the man was nobly born for he had the arrogance of rank and the confidence of privilege. He was certainly not a Norman noble, for Sir Guillaume knew all those men, and Sir Guillaume doubted the young man came from nearby Alençon or Maine, for he had ridden with those forces often enough, but the sallow cast of the stranger’s skin suggested he came from one of the Mediterranean provinces, from Languedoc perhaps, or Dauphine, and they were all mad down there. Mad as dogs. Sir Guillaume did not even know the man’s name.

‘Some men call me the Harlequin,’ the stranger had answered when Sir Guillaume had asked.

‘Harlequin?’ Sir Guillaume had repeated the name, then made the sign of the cross for such a name was hardly a boast. ‘You mean like the hellequin?’

‘Hellequin in France,’ the man had allowed, ‘but in Italy they say harlequin. It is all the same.’ The man had smiled, and something about that smile had suggested Sir Guillaume had best curb his curiosity if he wanted to receive the remaining nine hundred livres.

The man who called himself the Harlequin now stared at the misty shore where a stumpy church tower, a huddle of vague roofs and a smear of smoke from the smouldering fires of the saltpans just showed. ‘Is that Hookton?’ he asked.

‘So he says,’ Sir Guillaume answered, jerking his head at the shipmaster.

‘Then God have mercy on it,’ the man said. He drew his sword, even though the four boats were still a half-mile from shore. The Genoese crossbowmen, hired for the voyage, made the sign of the cross, then began winding their cords as Sir Guillaume ordered his banner raised to the masthead. It was a blue flag decorated with three stooping yellow hawks that had outspread wings and claws hooked ready to savage their prey. Sir Guillaume could smell the salt fires and hear the cockerels crowing ashore.

The cockerels were still crowing as the bows of his four ships ran onto the shingle.

Sir Guillaume and the Harlequin were the first ashore, but after them came a score of Genoese crossbowmen, who were professional soldiers and knew their business. Their leader took them up the beach and through the village to block the valley beyond, where they would stop any of the villagers escaping with their valuables. Sir Guillaume’s remaining men would ransack the houses while the sailors stayed on the beach to guard their ships.

It had been a long, cold and anxious night at sea, but now came the reward. Forty men-at-arms invaded Hookton. They wore close-fitting helmets and had mail shirts over leather-backed hacquetons, they carried swords, axes or spears, and they were released to plunder. Most were veterans of Sir Guillaume’s other raids and knew just what to do. Kick in the flimsy doors and start killing the men. Let the women scream, but kill the men, for it was the men who would fight back hardest. Some women ran, but the Genoese crossbowmen were there to stop them. Once the men were dead the plundering could begin, and that took time for peasants everywhere hid whatever was valuable and the hiding places had to be ferreted out. Thatch had to be pulled down, wells explored, floors probed, but plenty of things were not hidden. There were hams waiting for the first meal after Lent, racks of smoked or dried fish, piles of nets, good cooking pots, distaffs and spindles, eggs, butter churns, casks of salt–all humble enough things, but sufficiently valuable to take back to Normandy. Some houses yielded small hoards of coins, and one house, the priest’s, was a treasure-trove of silver plate, candlesticks and jugs. There were even some good bolts of woollen cloth in the priest’s house, and a great carved bed, and a decent horse in the stable. Sir Guillaume looked at the seventeen books, but decided they were worthless and so, having wrenched the bronze locks from the leather covers, he left them to burn when the houses were fired.