Полная версия

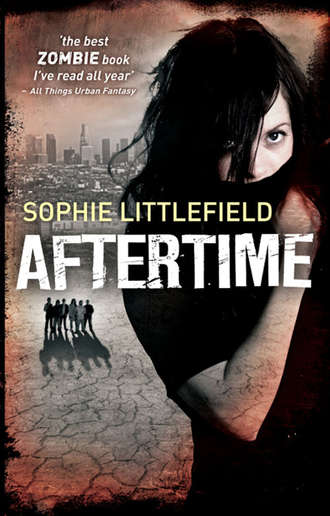

Aftertime

“He rescued them?”

“Yeah, he got this whole family, Jed and—Jed’s that guy who was babysitting with me. He’s sixteen. His parents and his brothers and a bunch of other people, too. Smoke helped them get out. And when they came here his hair was burned but that was all. He smelled like smoke, but he wasn’t burned, and people said it was a miracle. I don’t know if it was really a miracle but …”

The girl seemed suddenly embarrassed.

Cass followed a stray impulse and covered the girl’s hand with her own. Sammi’s skin was warm and she could feel her strong pulse at her wrist.

“I don’t know,” she said softly. “Maybe there’s still room for a miracle or two in the world.”

“Maybe,” Sammi said. She sounded like she thought Cass was going to need one.

07

LATE IN THE AFTERNOON, SMOKE RETURNED. Sammi was long gone, not wanting to worry her mother any more than she already had. Cass’s heart went out to the girl; she’d once walked the same complicated tightrope of parental loyalty and teenage rebellion, the challenges of school and friends and her father’s absence. Aftertime, everything was turned upside down. Kids, with their more elastic notions of what was real, rebounded and adapted while the adults struggled.

Except for the ones who lost their families. Aftertime orphans did not fare well. They were responsible for much of the looting and destruction that happened now—the ones who managed to escape predators, whose movements were no longer tracked and monitored. They found each other somehow, their senses tuned to the same frequency of grief and anger, and formed gangs who roamed the streets with breathtaking indifference to the danger, destroying everything in their path—just as everything that they had loved had been destroyed. Cass didn’t doubt that the bands of fake Beaters that Nora had mistaken her for were comprised of kids like these.

Sammi had already lost one parent. Cass prayed that the girl’s mother would stay safe.

Smoke brought plates piled with food and two plastic bottles filled with murky boiled water. There was a salad of kaysev greens dressed with oil and vinegar. There were also three blackened strips of jerky.

The aroma caused Cass to salivate, and she could practically taste the salty meat. Still, before accepting the plate, she asked: “Why?”

Smoke didn’t meet her gaze. “They want something in return,” he said. “News … there are a lot of people who won’t make the trip anymore. In the last couple of weeks it’s become a lot more dangerous. There’s been trouble, and not just from the Beaters.”

“What do you mean?”

Smoke made a dismissive gesture. “Long story. I’ll tell you about it on the road. But just folks with their own ideas about who ought to be running things.”

“What, you mean like who’s in charge here?” Cass saw a chance to ask something that she had been wondering. “Who is, anyway? You?”

“Not me,” Smoke said with finality. “We’re a collective here, we make decisions as a group. But look, like I said, it’s a long story. We’ll have time for it later, but now you should eat.”

“But …” Cass gestured at the plate. “What kind of stores do you have?”

Smoke shrugged, but his unconcern wasn’t convincing. “Quite a bit, actually. We still go raiding. Me, some of the others. There are still houses within a mile or two that haven’t been cleared yet. We only do one a night, take five or six of us and go.”

Cass nodded. She had come across some of these houses herself, even sheltered in them.

“What about the Wal-Mart?”

Smoke shook his head. “Beaters got there first. Nested all over it. There’s still a lot of canned food and other stuff in there but we can’t touch it.”

It was an older store, up Highway 161 outside the Silva town limits. It didn’t sell produce or meat, but that would actually be an advantage, since there would be no spoilage. And there would be medicine. Diapers, clothes, toiletries, processed foods. Winter coats and gloves. Boots.

“But we’re doing okay,” Smoke continued. “We got to the Village Market early on.”

Cass knew the place, a mom-and-pop grocery in a strip mall that stocked high-end gourmet stuff for weekenders and skiers. “Wasn’t it mostly cleared out back during the Siege?”

“Yeah, but we went back and finished the job. You know—people were panicking. Grabbing stuff. We’ve found things in houses … People will have a whole room full of bottled water, frozen dinners and shit they just left out when they couldn’t fit it in their freezers. Not that it mattered.”

Not after the power went out. Cass shook her head at the waste.

“We’ve got about five thousand cans. We’re trying to save the bottled water we have, and just rely on the creek. There’s some cereal, pasta, rice. Spices … not much meat, this is pretty much the end of it,” he said, pointing at the jerky. Cass noticed that his own plate held only salad and cold kaysev cakes. “Medicine … We got into the clinic, and there’s a woman here who was a doctor, a couple others, a nurse and a paramedic. So we have antibiotics, painkillers, bandages, like that.”

Cass chewed, trying to savor the salty jerky. She had never liked it Before, but now it tasted better than anything she’d ever eaten. “Do you think it’s true?” she asked after she took a sip from the bottle he’d brought. “Can you just live on kaysev? I mean, after …?”

After everything else is gone, she didn’t say. Because no matter how many stores they had managed to lay in here or anywhere else, the survivors would go through them eventually.

Smoke shrugged. “They certainly wanted us to believe that.”

Cass remembered the president’s prepared remarks, distributed to all the networks after he himself had gone to an undisclosed shelter. It was one of the final broadcasts before everything shut down. Paul Palmer, of KTXT, his hair looking like he’d done it himself, the part slightly askew, his eyes hollow and his voice wavering. It was a few days before the media disappeared forever—and only a matter of hours before the planes left air bases in Brunswick and Pensacola and Fort Worth and China Lake and Everett, loaded with their secret freight, tested and developed and grown in a dozen different locations across the U.S. Paul Palmer hadn’t even bothered to conceal the fact that he was reading from the teleprompter: “Full-spectrum nutritional mass,” he’d intoned. Code name K734IV, later shortened to K7 and then kaysev. Protein, calcium, vitamins, fiber.

“They could have been lying, though,” Cass said. “They obviously never tested it. I mean … if they had, they would have figured out about the blueleaf before they went and dumped seed over thousands of square miles.”

“Cass … you should know. Blueleaf’s only in California. At least, it was, unless it’s drifted.”

“Yeah, I’ve heard that,” Cass said, remembering Sammi’s story. “Only that’s just one more rumor. The only people who know are the pilots who dumped it, and even they don’t know what was in the seed mix.”

“No,” Smoke said quietly. “It’s true. Travis was the only base that went for it. Even China Lake turned it down, but they were doubling back over the same flight patterns as Travis so it didn’t matter.”

“How could you possibly know that?”

Smoke was silent for a moment, not meeting her eyes. “Because I was working in Fairfield at the time. Practically right next door to Travis. I used to drink with some of those guys.”

“But—wouldn’t that be confidential? Why would they open up to some guy in a bar?”

Smoke’s face darkened and his mouth went tight. “It was more than just a bar conversation. We were … friends. And I guess they needed to talk, when they got back from taking the kaysev up. Those guys were career pilots—that’s what they knew. Who they were. They knew it was the last flight they were ever going to take. So yeah, they talked.”

Cass thought about what he was saying. It was tantalizing to think there was part of the world—part of the country, even—that was still free of Beaters. A place where people didn’t live in constant terror.

But there was something off about Smoke’s story, about the way he wouldn’t look at her, at the barely concealed emotion in his voice.

“How would the pilots know what they were flying?” she demanded. “I mean, the military’s never been known for transparency. I would think something like that would be—what do you call it?—need-to-know. Especially if there was disagreement about what exactly they were going to distribute.”

Smoke shrugged. “Look, I only told you because … well, I thought it might give you hope.”

Cass didn’t believe him, but she wasn’t ready to let the conversation drop. “Why are you still here? If you’re so sure blueleaf’s only in California?”

“It’s way too unstable to try to make it out of state now. That’s got to be a hundred miles, most of it over-mountain.”

“Sammi told me other people have done it.”

Smoke laughed bitterly. “Yeah? What she told you was that other people tried. I met that guy. The one she’s talking about. Tried to talk him out of it, but he was determined, was one of those new roaming prophet-preachers. I bet he didn’t make it twenty miles up the road on foot.”

I did, Cass thought darkly. She’d made it farther than that, alone, with nothing but her wits.

Although she’d had Ruthie to live for. Maybe that had bought her survival.

Smoke seemed to have lost any interest in the conversation. He reached for her plate and Cass didn’t stop him; she allowed him to scrape the last of her meal onto his own plate and collect her empty bottle.

“I’ll take care of the dishes,” he said. “I’ve packed for both of us. We’ll leave in an hour or so. There’s wash water in the courtyard, if you want it. Women use it after dinner, then the kids. Men wait until morning. This is your chance—they’re expecting you. They’ll have supplies for you.” He hesitated. “I told them you were shy. That you’d want to keep your undershirt on, your underwear.”

He was gone before Cass could object—or thank him.

08

CASS FOLLOWED THE SOUND OF LAUGHTER, staying to the long shadows under the eaves. She’d already decided that if either Sammi or her mother were in the courtyard, she’d retreat without showing herself. She’d done enough damage to the fragile network of relationships in the school.

But the four women clustered around the makeshift tub were strangers. The tub was really more of a giant trough composed of sections of white plastic pipe that had been capped off and propped up on a pair of sawhorses. It had been filled with water that steamed in the rapidly cooling evening. A small fire crackled in the hearth a few yards away, a neat stack of burning madrone branches giving off a spicy, pleasant smell. Several pots of different sizes simmered on the grate above, and Cass guessed they poured the boiling water into the tub to keep the communal bath warm, and to replace what sloshed and splashed out with their movements.

Two of the four women were naked except for plastic flip-flops, and one of them held a nearly new bar of soap. The naked women washed, passing the soap back and forth. One of the other women was undressing, hopping from foot to foot as she stripped off her clothes and tossed them into a pile. The fourth woman had put her clothes back on and was toweling her hair. She was telling some sort of story that had the others cracking up, but when they noticed Cass approaching they all went silent.

“I’m sorry,” Cass said. “I didn’t mean to … Smoke said I might be able to wash. Except … I, um … “

“We have extra towels,” the woman who was undressing said, offering a tentative smile. “I brought two. I wasn’t sure if you … It’s pretty casual. We keep the water hot for a couple of hours and people just show up whenever.”

“Some people, anyway,” one of the naked women said. She was a well-built girl in her early twenties who didn’t seem the least bit self-conscious about dragging her soapy washcloth up and over her wide thighs, her rounded stomach. “Some folks, I don’t think they’ve had a bath since they got here. They get kind of unfresh, you know what I’m sayin’?”

She gave Cass a friendly wink as her companion flicked her with her own washcloth. “Not everyone’s as comfortable strutting around buck naked as you,” she scolded, grinning. “Forgive Nance here. She’s got no manners.”

“I, um …” Cass said, swallowing. “Is it okay … Do you mind if I don’t … uh, if I keep …” She hugged herself tightly, battling her warring desires to keep the evidence of her attack hidden, and to wash her filthy body.

“It’s okay,” the first woman said gently, handing her a small towel and a folded washcloth. They weren’t terribly clean, but Cass took them gratefully. She set the towel on the ground and stripped out of her overshirt and pants before she could change her mind, keeping her eyes downcast, and then approached the trough wearing only the nylon tank and panties that she’d been wearing beneath her clothes all this time. There were only a few scars on the backs of her thighs, and they had healed to barely distinguishable discolorations, but the gouges on her back were still raw and obvious. She knew this from tracing them with her fingers—the undeniable evidence that she’d been torn at by Beaters.

But there was more to her discomfort. It had also been years since she had undressed in front of another woman, and she felt her skin burn with shame as the others watched her.

It was different with men. She’d been with so many; she’d stopped counting one weekend when, by Sunday, she couldn’t remember the name of the one she brought home Friday. She hadn’t been self-conscious—hadn’t been conscious of anything, really, other than the driving need. Not a hunger for the coupling itself, but a need to beat her pain and confusion into a thing that could be contained again, could be put away far enough in the depths of her heart that she could keep going. Keep living. To get to that place she had to use her body, to show and undress and flaunt it, all of which was done without a second thought.

But now she felt hot shame color her face as her nipples hardened under the tight shirt, exposed to the evening chill. She had no bra—what would these women think of that? Cass didn’t know what to make of it herself—on the day she woke up, when she stumbled to her feet and tried to work the kinks out of her mysteriously abused limbs—she’d gone to tug at her bra, a habit of decades, and found it wasn’t there.

Cass hooked her thumbs in her socks and pulled them off, tossing them on the pile. There was nothing more that she could take off.

“I’ll—why don’t I …?” the woman who had been telling a story said. She made a move toward Cass’s clothes pile and hesitated. She looked Cass in the eye and spoke slowly and clearly. She was old enough to be a grandmother—old enough to be Ruthie’s grandmother, anyway. She had several inches of silver roots, an expensive dye job now losing ground, what must have been a severe bob softening to a wispy cut around her chin. “I’m Sonja,” she said carefully. “If you don’t mind, I’ll take these things, bring you back clothes that are clean, that you can wear on your … That will be good for traveling.”

Cass made a sound in her throat, a rusty and ill-used sound that was meant to convey gratitude. Hot dampness pricked at her eyes and she found that her lips did not move well. But Sonja just nodded and swept up the mess of clothes, hugging them against her body as though they didn’t stink, as though Cass had chosen and treasured them, rather than the truth—that she couldn’t say who she’d taken them from and what she’d done to the person who wore them before.

Cass wanted to watch Sonja walk away, to watch the filthy and hated rags disappear, but she knew that if she did she wouldn’t be able to concentrate on the bath, and the bath was a rare treat. She had not had or even allowed herself to dream of having such a thing in such a long time. There had been several moonlight splashes in the streams and creeks that crisscrossed the foothills, but the water never came up any farther than midankle, and no matter how Cass cupped her hands and splashed, she succeeded only in wetting her clothes and her skin, never cleansing them.

She approached the trough, the concrete cold and rough on her bare feet, focusing on the steam that rose into the evening air.

Out of the corner of her eye she saw the woman who was undressing pause, her jeans folded in her hands. She had not yet spoken, and unlike the others, she had made no move to welcome Cass. Hostility came off her in waves. The others had somehow made their peace with Cass, with what she had done to Sammi—but this woman did not want her there.

Cass inhaled deeply of the steam. Someone had crumbled something aromatic into the water, bath beads or powder or something else that perfumed the air with lavender and created a thin layer of white bubbles. She longed to dip her fingertips into the water.

She was so filthy. She could barely abide herself, and she wanted desperately to wash even a little of her shame away.

Instead she forced herself to turn away from the water, toward the silent woman. “I’ll go, if you want me to,” she offered quietly.

But the woman—she was a handsome woman with a short, no-nonsense haircut and sharp cheekbones—picked up her shoes and socks and glared at Cass. “No, I’ll go,” she muttered, and stalked away.

“I’m sorry,” Cass said to the others, her voice barely more than a whisper. “I should—”

“Stay,” one of the women said. “I’m Gail. Trust me, you need this way worse than she does.”

Cass was grateful, but she stared down at her hands, crisscrossed with cuts from running into dead shrubs and trees, and from falling in the dark. The nails were black and broken, her wrists creased with dirt. Her own odor was strong enough that she caught sour whiffs when she moved; she could only imagine how she smelled to others. “If you don’t mind,” she said, suddenly near tears and more humbled than she had ever felt in her life. “I’d like to stay.”

“I was about done,” Gail said, flipping thick brown braids over her shoulders and stepping aside to make room. “But don’t worry, I’ll stick around and chat.”

She stepped closer, her smile slipping when her glance fell to the nearly healed wounds on Cass’s arms. When she looked in Cass’s eyes again, her curiosity was edged with sadness.

“Did you do that?” she asked, and for one heart-skipping moment Cass thought Gail knew, that she had guessed, about the attack, the Beaters, everything.

And then the truth hit her, bringing clarity, but no lessening of shame.

Gail thought she’d harmed herself.

And she wasn’t wrong. Not about the story, only about the details.

There were days … dark days, when the end of the evening approached with no relief in sight, no one to slip into the shadows with, no strong man to bend her over double until there was no room for her own regrets, nights when every shot she downed added to her screaming headache without ever bringing the blessed numb of forgetting. And on those nights, once or twice … or three or four times … she’d found that sharp thing, the shard of broken ashtray, the coiled end of the corkscrew, the dull knife a bartender cut limes with…. She found the thing and she traced the shape of her shame until she could finally focus on the pain and forget the rest.

So, yes. Once, she’d borne the road map of shame on her skin. And was this really so different, these marks made by her own hands, in a fever she didn’t remember?

She hung her head and blinked at the hot mist in her eyes. Immediately Gail put her hand, warm and comforting, on Cass’s wrist, in the small band of unmolested flesh between her hand and the first of the chewed places.

“I’m sorry,” Gail murmured. “Please, just … just forget I said anything. Past is past here, if you want it to be. Everyone gets to start again.”

Cass shivered, unable to speak.

“Well, look,” Nance said, interrupting the moment with deliberate cheer. “Look, we’re just glad you’re here. You’re the first new face we’ve had in … well, a while. I’ve been going nuts here with all these yokels.”

“Nance isn’t cut out for small-town living,” Gail said, withdrawing her hand after a final squeeze. The moment had passed, nothing more than milkweed on the breeze. “She’s way too upscale for the rest of us.”

“I’m from Oakland,” Nance said. “I just came up here to help my mother when things went bad. I never dreamed I’d get stuck here.”

“Nance isn’t much of a nature person,” Gail said. “She keeps wishing she’d wake up and there’d be room service.”

“I put in this shower last year,” Nance said. “In my condo? One of those rain shower ones? There were jets along the side, steam … “

“And I bet you never had any trouble finding someone to share it with you, right?” Gail said, winking at Cass. “Nance also doesn’t like the men here.”

Cass dipped her washcloth into the warm water, savoring the sensation of the water closing over her fingers, her hand, her wrist. Slowly, she trailed the cloth in an underwater figure eight. “I’ll ruin this water. It’ll be filthy when I’m done.”

Gail shrugged. “It wasn’t exactly crystal clear to start with. We just drag it up from the creek. We don’t bother to strain it or purify it when it’s just for washing.”

Nance wrinkled her nose. “Yeah, it smells a little like rotting fish. I don’t know what we’ll do when we run out of shower gel to hide the smell.”

“We’ll stink,” Gail said. “Just like we do now, only by then we’ll all be so used to it that it won’t matter.”

It was all the encouragement Cass needed. She submerged her arms up to her elbows, then lowered her face into the water and stayed under as long as her breath held out. She came up with the water dripping down her face and blinked it out of her eyes. “Ohhh,” she breathed.

“Tell you what,” Gail said. “I have a little shampoo left.”

“Oh, I couldn’t—” Cass said.

“Yeah, you can.” Gail reached into a plastic tote. “Put your hand out.”

Cass did as she was told and Gail squeezed out a dollop of creamy shampoo. It smelled like rosemary, and it was familiar; Cass had a bottle of it once, long ago. She held it up to her face and breathed as deeply as she could, trying to imprint the memory of the smell in her brain. Then she rubbed it onto her cropped hair and began to work it into her scalp, taking her time, making small circles.

The hair around her hairline was growing in soft and fine; Cass wondered if pulling it out had damaged the roots in some way. Before, when she was a teenager, she remembered her mother warning her that if she plucked her eyebrows too often the hair wouldn’t grow back. She had believed her mother. Before Byrn. When it was just the two of them, her mother taking such care in her mirror in the morning and before dates, Cass sitting on the edge of the tub to talk to her. She thought that might have been when her mother was happiest, when she was getting ready for a new man. Before there had been time for him to disappoint her or, in the end, to leave her. When it was all possibility, when Jack or David or Hunt was still new to her. “I have a good feeling about this one,” she would always say, winking at Cass as she slipped her blouse over her head, adjusting her breasts in her satiny bra, buttoning just enough buttons to give a hint of cleavage.

She always had a good feeling, before.

Even with Byrn.

Cass forced the thought from her mind. When the shampoo was exhausted, the dirt and grease in her hair overwhelming the lather, she lowered her head and let the water come up over her scalp and the back of her neck, down her shirt. She swept her hair through the water, rinsing out all the shampoo. Then she came up sputtering a second time, her hair plastered wet and warm against her shoulders.

Nance made a show of pretending to look into the trough. “Can’t even tell,” she said. “We’ll be able to wash all the kids and a few stray dogs in here, too.”