Полная версия

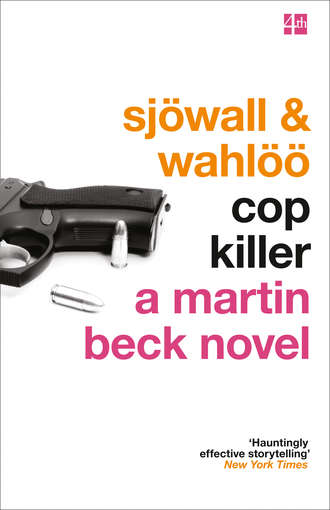

Cop Killer

‘It's a hell of a long time since I had anything in my belly,’ Kollberg said.

Martin Beck didn't answer. He wasn't hungry, but he had a sudden longing for a cigarette. He had pretty much stopped smoking two years before, after a serious gunshot wound in the chest.

‘A man my size really needs a little more than one hard-boiled egg a day,’ Kollberg went on.

If you didn't eat so much you wouldn't be that size and you wouldn't need to eat so much, Martin Beck thought, but he said nothing. Kollberg was his best friend, and it was a touchy subject. He didn't want to hurt his feelings and he knew Kollberg was in an especially bad mood whenever he was hungry. He also knew that Kollberg had urged his wife to keep him on a reducing diet that consisted exclusively of hard-boiled eggs. The diet was not a great success, however, since breakfast was the only meal he ate at home. He ate his other meals out, or at the police canteen, and they did not consist of hard-boiled eggs – Martin Beck could vouch for that.

Kollberg nodded in the direction of a brightly lit pastry shop half a block away.

‘I don't suppose you'd …’

Martin Beck opened the door on the kerb side and put out one foot.

‘Okay. What do you want? Danish?’

‘Yes, and a mazarin,’ Kollberg said.

Martin Beck came back with a bag of pastries, and they sat quietly and watched the building where The Breadman was while Kollberg ate, dribbling crumbs all over his uniform. When he was finished eating, he pushed the seat back one more notch and loosened his shoulder belt.

‘What have you got in that holster?’ Martin Beck asked.

Kollberg unbuttoned the holster and handed him the weapon. It was a toy pistol of Italian manufacture, well made and massive and almost as heavy as Martin Beck's own Walther, but incapable of firing anything but caps.

‘Nice,’ said Martin Beck. ‘Wish I'd had one like that when I was a kid.’

It was common knowledge on the force that Lennart Kollberg refused to carry arms. Most people were under the impression that his refusal was based on some kind of pacifist principles and that he wanted to set a good example, since he was the police department's most enthusiastic advocate of eliminating weapons altogether under normal circumstances.

And all of that was true, but it was only half the truth. Martin Beck was one of the few people who knew of the primary reason for Kollberg's stand.

Lennart Kollberg had once shot and killed a man. It had happened more than twenty years before, but Kollberg had never been able to forget, and it was a good many years now since he had carried a weapon, even on critical and dangerous assignments.

The incident took place in August 1952, while Kollberg was attached to the second Söder division in Stockholm. Late one evening, there was an alarm from Långholm Prison, where three armed men had attempted to free a prisoner and had shot and wounded one of the guards. By the time the emergency squad with Kollberg reached the prison, the men had smashed their car into a railing up on Väster Bridge while trying to get away, and one of the men had been captured. The other two had managed to escape by running into Långholm Park on the other side of the bridge abutment. Both of them were thought to be armed, and since Kollberg was considered a good shot, he was included in the group that was sent into the park to try and surround the men.

With his pistol in hand, he had climbed down towards the water and then followed the shore away from the glow of the lights up on the bridge, listening and peering into the darkness. After a while, he stopped on a smooth granite outcropping that projected out into the bay and bent over and dipped one hand in the water, which felt warm and soft. When he straightened up again, a shot rang out, and he felt the bullet graze the sleeve of his coat before it hit the water several yards behind him. The man who fired it had been somewhere in the darkness among the bushes on the slope above him. Kollberg immediately threw himself flat on his face and squirmed into the protective vegetation along the shore. Then he started to crawl up towards a boulder that loomed over the spot where he thought the shot had come from. And sure enough, when he reached the huge rock he could see the man outlined against the light, open water of the bay. He was only fifty or sixty feet away. He was turned halfway towards Kollberg, holding his pistol ready in his raised hand and moving his head slowly from side to side. Beside him was the steep slope down into Riddar Bay.

Kollberg aimed carefully for the man's right hand. Just as his finger squeezed off the shot, someone suddenly appeared behind his target and threw himself towards the man's arm and Kollberg's bullet and then just as suddenly vanished again down the hillside.

Kollberg did not immediately realize what had happened. The man started running, and Kollberg shot again and this time hit him in the knee. Then he walked over and looked down the hill.

Down at the edge of the water lay the man he had killed. A young policeman from his own division. They had often been on duty together and always got along unusually well.

The story was hushed up, and Kollberg's name was never even mentioned in connection with it. Officially, the young policeman died of an accidental bullet wound, a wild shot from nowhere, while pursuing a dangerous criminal. Kollberg's chief gave him a little lecture in which he warned him against brooding and self-reproach and closed by pointing out that Charles XII himself had once shot to death his head groom and close friend through carelessness and inadvertence and that consequently it was the sort of accident that could happen to the best of men. And that was supposed to be the end of it. But Kollberg never really recovered from the shock, and for many years now, as a result, he always carried a cap pistol whenever he needed to appear to be armed.

Neither Kollberg nor Martin Beck thought about any of this as they sat in the patrol car waiting for The Breadman to show himself.

Kollberg yawned and squirmed in his seat. It was uncomfortable sitting behind the wheel, and the uniform he had on was too tight. He couldn't remember the last time he'd worn one, but it was definitely a long time ago. He had borrowed the one he was wearing, and even though it was small, it was not nearly as tight as his own old uniform would have been, which was hanging on a hook in a cupboard at home.

He glanced at Martin Beck, who had sunk deeper into the seat and was staring out through the windscreen.

Neither one of them said anything. They had known each other for a long time; they had been together on the job and off for many years and had no need to talk just for the sake of talking. They had spent innumerable evenings this same way – in a car on some dark street, waiting.

Since he became chief of the National Murder Squad, Martin Beck did not actually need to do much trailing and surveillance – he had a staff to attend to that. But he often did it anyway, even though that kind of assignment was usually deadly dull. He didn't want to lose touch with this side of the job simply because he'd been made chief and had to spend more and more of his time dealing with all the troublesome demands made by a growing bureaucracy. Even if the one did not, unfortunately, preclude the other, he preferred sitting and yawning in a patrol car with Kollberg to sitting and trying not to yawn in a meeting with the National Police Commissioner.

Martin Beck liked neither the bureaucracy, the meetings, nor the Commissioner. But he liked Kollberg very much and had a hard time picturing this job without him. For a long time now, Kollberg had been expressing an occasional desire to leave the police force, but recently he had seemed more and more determined to carry out this impulse. Martin Beck wanted neither to encourage nor discourage him. He knew that Kollberg's feeling of solidarity with the police force had come to be virtually non-existent and that his conscience bothered him more and more. He also knew it would be very hard for him to get a satisfying and roughly equivalent job. In a time of high unemployment, when young people in particular, but even university graduates and well-trained professionals of every description, were going without work, the prospects for a fifty-year-old former policeman were not especially bright. For purely selfish reasons, he wanted Kollberg to stay on, of course, but Martin Beck was not a particularly selfish person, and the thought of trying to influence Kollberg's decision had never crossed his mind.

Kollberg yawned again.

‘Lack of oxygen,’ he said and rolled down the window. ‘We were lucky to have been constables back in the days when cops still used their feet to walk on and not just to kick people with. You can get claustrophobia sitting in here like this.’

Martin Beck nodded. He too disliked the feeling of being shut in.

Both Martin Beck and Kollberg had begun their careers as policemen in Stockholm in the mid-forties. Martin Beck had worn down the pavements in Norrmalm, and Kollberg had trudged the narrow alleyways of the Old City. They hadn't known one another in those days, but their memories from that time were by and large the same.

It got to be 9.30. The pastry shop closed, and the lights started going out in many of the windows down the street. The lights were still on in the flat where The Breadman was visiting.

Suddenly the door opened across the street, and The Breadman stepped out on to the pavement. He had his hands in the pockets of his coat and a cigarette in the corner of his mouth.

Kollberg put his hands on the steering wheel and Martin Beck sat up in his seat.

The Breadman stood quietly outside the doorway, calmly smoking his cigarette.

‘He doesn't have any bag with him,’ Kollberg said.

‘He might have it in his pockets,’ Martin Beck said. ‘Or else he's sold it. We'll have to check on who he was visiting.’

Several minutes passed. Nothing happened. The Breadman gazed up at the starry sky and seemed to be enjoying the evening air.

‘He's waiting for a taxi,’ said Martin Beck.

‘Seems to be taking a hell of a long time,’ Kollberg said.

The Breadman took a final drag on his cigarette and flicked it out into the street. Then he turned up his coat collar, stuck his hands back into his pockets, and started across the street towards the police car.

‘He's coming over here,’ Martin Beck said. ‘Damn. What do we do? Take him in?’

‘Yes,’ Kollberg said.

The Breadman walked slowly over to the car, leaned down, looked at Kollberg through the side window and started to laugh. Then he walked around behind the boot and up on to the pavement. He opened the door to the front seat where Martin Beck was sitting, leaned over, and let out a roar of laughter.

Martin Beck and Kollberg sat quietly and let him laugh, for the simple reason that they didn't know what else to do.

The Breadman finally recovered somewhat from his paroxysms.

‘Well, now,’ he said, ‘have you finally been demoted? Or is this some kind of fancy-dress party?’

Martin Beck sighed and climbed out of the car. He opened the door to the back seat.

‘In you go, Lindberg,’ he said. ‘We'll give you a lift to Västberga.’

‘Good enough,’ said The Breadman good-naturedly. ‘That's closer to home.’

On the way in to Södra police station, The Breadman told them he'd been visiting his brother in Råsunda, which was quickly confirmed by a patrol car despatched to the spot. There were no weapons, money, or stolen goods in the flat. The Breadman himself was carrying twenty-seven kronor.

At a quarter to twelve they had to release him, and Martin Beck and Kollberg could start to think about going home.

‘I never would have thought you guys had such a sense of humour,’ said The Breadman before he left. ‘First this bit with the costumes – now that was fun. But the part I liked best was seeing PIG written on the back of your car. I couldn't have done better myself.’

They themselves were only moderately amused, but his hearty laughter reached them from a long way down the stairs. He sounded almost like the Laughing Policeman.

In point of fact, it didn't matter much. They would catch him soon enough. The Breadman was the type who always gets caught.

And for their own part, they would soon have other things to think about.

3

The airport was a national disgrace and lived up to its reputation. The actual flight from Arlanda Airport in Stockholm had taken only fifty minutes, but now the plane had been circling over the southernmost part of the country for an hour and a half.

‘Fog,’ was the laconic explanation.

And that was exactly what might have been expected, for the airfield had been built – once the inhabitants were displaced – in one of the foggiest spots in Sweden. And as if that weren't enough, it lay in the middle of a well-known migratory bird route and at a very uncomfortable distance from the city.

In addition, it had destroyed a natural wilderness that should have been protected by law. The damage was extensive and irreparable and constituted an act of gross ecological malfeasance, typical of the anti-humanitarian cynicism that had become increasingly characteristic of what the government called A More Compassionate Society. This expression, in turn, represented a cynicism so boundless that the common man had difficulty grasping it.

The pilot finally grew tired and brought the plane down fog or no fog, and a handful of pale, sweating passengers filed sparsely into the terminal building.

Inside, the very colour scheme – grey and saffron yellow – seemed to underline the odour of incompetence and corruption.

Martin Beck had several unpleasant hours to look back upon. He had always loathed flying, and the new planes didn't make it any better. The jet had been a DC-9. It had begun by climbing precipitously to an altitude that was incomprehensible to the average earthbound human being. Then it had raced across the countryside at an abstract speed, only to conclude in a monotonous holding pattern. The liquid in the paper mugs was said to be coffee and produced immediate nausea. The air in the cabin was noxious and sticky, and his few fellow passengers were harried technocrats and businessmen who glanced constantly at their watches and shuffled nervously through the papers in their attaché cases.

The arrivals hall could not even be called uncomfortable. It was monstrous, a design catastrophe that would make a dusty bus station miles from anywhere seem lively and convivial by comparison. There was a hot-dog stand that served an inedible, nutrition-free parody of food, a newsstand with a display of condoms and smutty magazines, some empty conveyor belts for luggage, and a number of chairs that might have been designed during the heyday of the Spanish Inquisition. Add a dozen yawning policemen and bored customs officials, all of them undoubtedly there against their will, and one taxicab, whose driver had fallen asleep with the latest issue of a pornographic magazine spread across the steering wheel.

Martin Beck waited an unreasonably long time for his small suitcase, picked it off the belt and stepped out into the autumn fog.

A passenger stepped into the cab, and it drove off.

No one inside the arrivals hall had said anything or indicated in any way that they recognized him. They had seemed apathetic, almost as if they had lost the power of speech, or, in any case, lost all interest in using it.

The chief of the National Murder Squad had arrived, but no one seemed to appreciate the importance of that event. Not even the greenest of cub reporters could be bothered to drag them-selves out here to enrich their lives with card games, over-boiled wieners, and petrochemical soft drinks. Anyway, the so-called celebrities never showed up here.

There were two orange buses standing in front of the terminal. Plastic signs showed their destinations: Lund and Malmö. The drivers were smoking in silence.

The night was mild, and the air was humid. Misty halos surrounded the electric lights.

The buses drove off, one of them empty, the other with a single passenger. The other travellers hurried towards the long-term parking area.

Martin Beck's palms were still sweaty. He went back inside and searched out a men's room. The flushing mechanism was broken. There was a half-eaten hot dog and an empty vodka bottle in the urinal. Strands of hair clung to the greasy ring of dirt in the sink. The paper towel dispenser was empty.

This was Sturup Airport, Malmö. So new it still wasn't complete.

He doubted there was any point in completing it. In a way, it was perfect already – epitomizing the fiasco as it did.

Martin Beck dried his hands with his handkerchief. He went back outside and stood in the darkness for a moment feeling lonely.

He hadn't exactly expected the police band lined up in the arrivals hall, or the local chief of police out on horseback to receive him.

But perhaps he had expected something more than nothing at all.

He dug in his pocket for change and considered searching for a pay phone that did not have the cord to its receiver cut or its coin slot stuffed with chewing gum.

Lights cut through the fog. A black-and-white patrol car came sneaking along the ramp and swung in towards the door of the huge saffron-yellow box.

It was moving slowly, and when it drew even with the solitary traveller it came to a stop. The side window was rolled down, and a red-haired individual with skimpy police sideburns stared at him coldly.

Martin Beck said nothing.

After a minute or so the man raised his hand and beckoned to him with his finger. Martin Beck walked over to the car.

‘What are you hanging around here for?’

‘Waiting for transport.’

‘Waiting for transport! You don't say!’

‘Perhaps you can help me.’

The constable looked dumbfounded.

‘Help you? What do you mean?’

‘I've been delayed. I thought maybe I could use your radio.’

‘Who do you think you are?’

Without taking his eyes off Martin Beck, he threw several remarks back over his shoulder.

‘Did you hear that? He says he thought maybe he could use our radio. I reckon he thinks we're some kind of pimp service or something. Did you hear him?’

‘I heard,’ said the other policeman wearily.

‘Can you identify yourself?’ said the first policeman.

Martin Beck put his hand to his back pocket, but changed his mind. He let his arm drop.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘But I'd really rather not.’

He turned on his heel and walked back to his bag.

‘Did you hear that?’ the policeman said. ‘He says he'd rather not. He thinks he's pretty tough. Do you think he's tough?’

The sarcasm was so heavy that the words fell to the ground like bricks.

‘Oh, forget it,’ said the man who was driving. ‘Let's not have any more trouble tonight, okay?’

The redhead stared hard at Martin Beck for a long time. Then there was a mumbled conversation, and the car began to roll away. Sixty feet off it stopped again so the policemen could observe him in the rear-view mirror.

Martin Beck looked in a different direction and sighed heavily.

As he stood there at this moment, he could have been taken for anyone at all.

During the last year he had managed to get rid of some of his police mannerisms. He no longer invariably clasped his hands behind his back, for example, and he could now stand in one place for a short time without rocking back and forth on the balls of his feet.

Although he had put on a little weight, he was still, at fifty-one, a tall, fit, well-built man, with a slight stoop. He also dressed more comfortably than he had, though there was no laboured youthfulness in his choice of clothes – sandals, Levi's, turtleneck, and a blue Dacron jacket. On the other hand, it might be considered unconventional for a detective superintendent of police.

For the two officers in the patrol car it was obviously difficult to swallow. They were still pondering the situation when a tomato-coloured Opel Ascona swung up in front of the terminal building and braked to a stop. A man climbed out and walked around the car.

‘Allwright?’ he said.

‘Beck.’

‘People generally get a chuckle out of that.’

‘A chuckle?’

‘You know, they laugh at the way I say Allwright.’

‘I see.’

Laughter did not come quite that easily to Martin Beck.

‘And you'll have to admit it is a silly name for a policeman. Herrgott Allwright. So I usually introduce myself that way, like it was a question. Allwright? It sort of flusters people.’

He stowed the suitcase in the boot of his car.

‘I'm late,’ he said. ‘No one knew where the plane was going to come down. I took a chance it would be Copenhagen, as usual. So I was already in Limhamn when I got the word it had landed here. Sorry.’

He peered enquiringly at Martin Beck, as if trying to determine whether his exalted guest was out of sorts.

Martin Beck shrugged his shoulders.

‘It doesn't matter,’ he said. ‘I'm not in any hurry.’

Allwright threw a glance at the patrol car, which remained in position with its engine idling.

‘This isn't my district,’ he said with a grin. ‘They're from Malmö. We'd better go before we get arrested.’

The man obviously had a ready laugh, which, moreover, was soft and infectious.

But still Martin Beck wouldn't smile. Partly because there wasn't all that much to smile at, and partly because he was trying to form an opinion of the other man – sketch out a sort of preliminary description.

Allwright was a short, bow-legged man – short, that is, for the police service. With his green rubber boots, his greyish-brown twill suit, and the sun-bleached safari hat on the back of his head, he looked like a farmer, or, at any rate, like a man with his own territory. His face was sunburned and weatherbitten, and there were laugh lines around the corners of his lively brown eyes. And yet he was representative of a certain category of rural policeman. A type of man who didn't fit in with the new conformist style and was therefore on his way to dying out, but was not yet completely extinct.

He was probably older than Martin Beck, but he had the advantage of working in calmer and healthier surroundings, which is not to say that they were calm and healthy, by any means.

‘I've been here almost twenty-five years. But this is a first for me. The National Murder Squad, from Stockholm, on a case like this.’

Allwright shook his head.

‘I'm sure everything will work out fine,’ said Martin Beck. ‘Or else…’

He finished the sentence silently to himself: Or else it won't work out at all.

‘Exactly,’ Allwright said. ‘You people from the Murder Squad understand this kind of case.’

Martin Beck wondered if that was the polite plural, or if he were really referring to both of them. Lennart Kollberg was on his way from Stockholm by car and could be expected the next day. He had been Martin Beck's right-hand man for many years.

‘The story's going to leak out pretty soon,’ Allwright said. ‘I saw a couple of characters in town today – reporters, I think.’

He shook his head again.

‘We're not used to this sort of thing. All this attention.’

‘Someone has disappeared,’ said Martin Beck. ‘There's nothing so unusual about that.’

‘No, but that's not the crux of the matter. Not at all. Do you want to hear about it?’

‘Not right now, thanks. If you won't take it amiss.’

‘I never take anything amiss. Not my style.’

He laughed again, but stopped himself and added, soberly, ‘But then I'm not in charge of the investigation.’

‘Maybe she'll turn up. That's usually the way.’

Allwright shook his head for the third time.

‘I don't think so,’ he said. ‘In case my opinion makes any difference. Anyway, it's an open-and-shut case. Everyone says so. They're probably right. All this nonsense with the…I mean, excuse me, but calling in the Murder Squad and all that is just because of the unusual circumstances.’