Полная версия

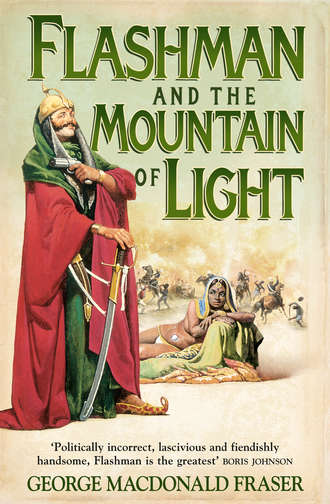

Flashman and the Mountain of Light

‘But what does it mean, Sir Harry?’

‘Well, ma’am, it means that two fellows were travelling by train, you see, and they were, I regret to say, intoxicated –’

‘Why, Harry!’ cries Elspeth, acting shocked, but the Queen just took another tot of whisky in her tea and bade me continue. So I told her that one chap said, where are we, and t’other chap replied, Wednesday, and the first chap said, Heavens, this is where I get out. Needless to say, it convulsed them – and while they recovered and passed the gingerbread, I asked myself for the twentieth time why we were here, just Elspeth and me and the Great White Mother, taking tea together.

You see, while I was used enough, in those later years, to being bidden to Balmoral each autumn to squire her about on drives, and fetch her shawl, and endure her prattle and those damned pipers of an evening, a summons to Windsor in the spring was something new, and when it included ‘dear Lady Flashman, our fair Rowena’ – the Queen and she both pretended a passion for Scott – I couldn’t think what was up. Elspeth, when she’d recovered from her ecstasy at being ‘commanded to court’, as she put it, was sure I was to be offered a peerage in the Jubilee Honours (there’s no limit to the woman’s mad optimism); I damped her by observing that the Queen didn’t keep coronets in the closet to hand out to visitors; it was done official, and anyway even Salisbury wasn’t so far gone as to ennoble me; I wasn’t worth bribing. Elspeth said I was a horrid cynic, and if the Queen herself required our attendance it must be something grand, and whatever was she going to wear?

Well, the grandeur turned out to be Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show1 – I concluded that I’d been dragged in because I’d been out yonder myself, and was considered an authority on all that was wild and woolly – and we sat in vile discomfort at Earl’s Court among a great gang of Court toadies, while Cody pranced on a white horse, waving his hat and sporting a suit of patent buckskins that would have laid ’em helpless with laughter along the Yellowstone. There was enough paint and feathers to outfit the whole Sioux Nation, the braves whooped and ki-yikked and brandished their hatchets, the roughriders curvetted, a stagecoach of terrified virgins was ambushed, the great man arrived in the nick of time blazing away until you couldn’t see for smoke, and the Queen said it was most curious and interesting, and what did the strange designs of the war paint signify, my dear Sir Harry?

God knows what I told her; the fact is, while everyone else was cheering the spectacle, I was reflecting that only eleven years earlier I’d been running like hell from the real thing at Little Bighorn, and losing my top hair into the bargain – a point which I mentioned to Cody later, after he’d been presented. He cried, yes, by thunder, that was one war-party he’d missed, and didn’t he envy me the trip, though? Lying old humbug. That’s by the way; I realised, when the Queen bore Elspeth and me back to Windsor, and bade us to tea à trois next day, that our presence at the show had been incidental, and the real reason for our invitation was something else altogether. A trifling matter, as it turned out, but it inspired this memoir, so there you are.

She wanted our opinion, she said, on a matter of the first importance – and if you think it odd that she should confide in the likes of us, the retired imperial roughneck of heroic record but dubious repute, and the Glasgow merchant’s daughter … well, you don’t know our late lamented Queen Empress. Oh, she was a stickler and a tartar, no error, the highest, mightiest monarch that ever was, and didn’t she know it, just – but if you were a friend, well, that was a different palaver. Elspeth and I were well out of Court, and barely half way into Society, even, but we’d known her since long ago, you see – well, she’d always fancied me (what woman didn’t?), and Elspeth, aside from being such an artless, happy beauty that even her own sex couldn’t help liking her, had the priceless gift of being able to make the Queen laugh. They’d taken to each other as young women, and now, on the rare occasions they met tête-à-tête, they blethered like the grandmothers they were – why, on that very day (when I was safely out of earshot) she told Elspeth that there were some who wanted her to mark her Golden Jubilee by abdicating in favour of her ghastly son, Bertie the Bounder, ‘but I shall do no such thing, my dear! I intend to outlive him, if I can, for the man is not fit to reign, as none knows better than your own dear husband, who had the thankless task of instructing him.’ True, I’d pimped for him occasional, but ’twas wasted effort; he’d have been just as great a cad and whoremaster without my tuition.

However, it was about the Jubilee she wanted our advice, ‘and yours especially, Sir Harry, for you alone have the necessary knowledge’. I couldn’t figure that; for one thing, she’d been getting advice and to spare for months on how best to celebrate her fiftieth year on the throne. The whole Empire was in a Jubilee frenzy, with loyal addresses and fêtes and junketings and school holidays and water-trough inaugurations and every sort of extravagance on the rates; the shops were packed with Jubilee mugs and plates and trumpery blazoned with Union Jacks and pictures of Her Majesty looking damned glum; there were Jubilee songs on the halls, and Jubilee marches for parades, and even Jubilee musical bustles that played ‘God Save the Queen’ when the wearer sat down – I tried to get Elspeth to buy one, but she said it was disrespectful, and besides people might think it was her.

The Queen, of course, had her nose into everything, to make sure the celebrations were dignified and useful – only she could approve the illuminations for Cape Town, the chocolate boxes for Eskimo children, the plans for Jubilee parks and gardens and halls and bird-baths from Dublin to Dunedin, the special Jubilee robes (it’s God’s truth) for Buddhist monks in Burma, and the extra helpings of duff for lepers in Singapore: if the world didn’t remember 1887, and the imperial grandmother from whom all blessings flowed, it wouldn’t be her fault. And after years in purdah, she had taken to gallivanting on the grand scale, to Jubilee dinners and assemblies and soirées and dedications – dammit, she’d even visited Liverpool. But what had tickled her most, it seemed, was being photographed in full fig as Empress of India; it had given her quite an Indian fever, and she was determined that the Jubilee should have a fine flavour of curry – hence the resolve to learn Hindi. ‘But what else, Sir Harry, would best mark our signal regard for our Indian subjects, do you think?’

Baksheesh, booze, and bints was the answer to that, but I chewed on a muffin, looking grave, and said, why not engage some Indian attendants, ma’am, that’d go down well. It would also infuriate the lordly placemen and toad-eaters who surrounded her, if I knew anything. After some thought, she nodded and said that was a wise and fitting suggestion – in the event, it was anything but, for the Hindi-wallah she fixed on as her special pet turned out to be not the high-caste gent he pretended, but the son of a puggle-walloper in Agra jail; if that wasn’t enough, he spread her secret Indian papers all over the bazaars, and drove the Viceroy out of his half-wits. Aye, old Flashy’s got the touch.2

At the time, though, she was all for it – and then she got down to cases in earnest. ‘For now, Sir Harry, I have two questions for you. Most important questions, so please to attend.’ She adjusted her spectacles and rummaged in a flat case at her elbow, breathing heavy and finally unearthing a yellowish scrap of paper.

‘There, I have it. Colonel Mackeson’s letter …’ She peered at it with gooseberry eyes. ‘… dated the ninth of February, 1852 … now where is … ah, yes! The Colonel writes, in part: “On this head, it will be best to consult those officers in the Company service who have seen it, and especially Lieutenant Flashman …”’ She shot me a look, no doubt to make sure I recognised the name ‘“… who is said to have been the first to see it, and can doubtless say precisely how it was then worn”.’ She laid the letter down, nodding. ‘You see, I keep all letters most carefully arranged. One cannot tell when they may be essential.’

I made nothing of this. Where the deuce had I been in ’52, and what on earth was ‘it’ on whose wearing I was apparently an authority? The Queen smiled at my mystification. ‘It may be somewhat changed,’ says she, ‘but I am sure you will remember it.’

She took a small leather box from the case, set it down among the tea things, and with the air of a conjurer producing a rabbit, raised the lid. Elspeth gave a little gasp, I looked – and my heart gave a lurch.

It ain’t to be described, you must see it close to … that glittering pyramid of light, broad as a crown piece, alive with an icy fire that seems to shine from its very heart. It’s a matchless, evil thing, and shouldn’t be a diamond at all, but a ruby, red as the blood of the thousands who’ve died for it. But it wasn’t that, or its terrible beauty, that had shaken me … it was the memory, all unexpected. Aye, I’d seen it before.

‘The Mountain of Light,’ says the Queen complacently. ‘That is what the nabobs called it, did they not, Sir Harry?’

‘Indeed, ma’am,’ says I, a mite hoarse. ‘Koh-i-Noor.’

‘A little smaller than you remember it, I fancy. It was recut under the directions of my dear Albert and the Duke of Wellington,’ she explained to Elspeth, ‘but it is still the largest, most precious gem in all the world. Taken in our wars against the Sikh people, you know, more than forty years ago. But was Colonel Mackeson correct, Sir Harry? Did you see it then in its native setting, and could you describe it?’

By God, I could … but not to you, old girl, and certainly not to the wife of my bosom, twittering breathlessly as the Queen lifted the gleaming stone to the light in her stumpy fingers. ‘Native setting’ was right: I could see it now as I saw it first, blazing in its bed of tawny naked flesh – in the delectable navel of that gorgeous trollop Maharani Jeendan, its dazzling rays shaming the thousands of lesser gems that sleeved her from thigh to ankle and from wrist to shoulder … that had been her entire costume, as she staggered drunkenly among the cushions, laughing wildly at the amorous pawings of her dancing boys, draining her gold cup and flinging it aside, giggling as she undulated voluptuously towards me, slapping her bare hips to the tom-toms, while I, heroically foxed but full of good intentions, tried to crawl to her across a floor that seemed to be littered with Kashmiri houris and their partners in jollity … ‘Come and take it, my Englishman! Ai-ee, if old Runjeet could see it now, eh? Would he leap from his funeral pyre, think you?’ Dropping to her knees, belly quivering, the great diamond flashing blindingly. ‘Will you not take it? Shall Lal have it, then? Or Jawaheer? Take it, gora sahib, my English bahadur!’ The loose red mouth and drugged, kohl-stained eyes mocking me through a swirling haze of booze and perfume …

‘Why, Harry, you look quite upset! Whatever is the matter?’ It was Elspeth, all concern, and the Queen clucked sympathetically and said I was distrée, and she was to blame, ‘for I am sure, my dear, that the sudden sight of the stone has recalled to him those dreadful battles with the Sikhs, and the loss of, oh, so many of our gallant fellows. Am I not right?’ She patted my hand kindly, and I wiped my fevered brow and confessed it had given me a start, and stirred painful recollections … old comrades, you know, stern encounters, trying times, bad business all round. But yes, I remembered the diamond; among the Crown Jewels at the Court of Lahore, it had been …

‘Much prized, and worn with pride and reverence, I am sure.’

‘Oh, absolutely, ma’am! Passed about, too, from time to time.’

The Queen looked shocked. ‘Not from hand to hand?’

From navel to navel, in fact, the game being to pass it round, male to female, without using your hands, and anyone caught waxing his belly-button was disqualified and reported to Tattersalls … I hastened to assure her that only the royal family and their, ah, closest intimates had ever touched it, and she said she was glad to hear it.

‘You shall write me an exact description of how it was set and displayed,’ says she. ‘Of course, I have worn it myself in various settings, for while it is said to be unlucky, I am not superstitious, and besides, they say it brings ill fortune only to men. And while it was presented by Lord Dalhousie to me personally, I regard it as belonging to all the women of the Empire.’ Aye, thinks I absently, Your Majesty wears it on Monday and the scrubwoman has it on Tuesday.

‘That brings me to my second question, and you, Sir Harry, knowing India so well, must advise me. Would it be proper, do you think, to have it set in the State Crown, for the great Jubilee service in the Abbey? Would it please our Indian subjects? Might it give the least offence to anyone – the princes, for example? Consider that, if you please, and give me your opinion presently.’ She regarded me as though I were the Delphic oracle, and I had to clear my mind of memories to pay heed to what she was saying.

So that, after all the preamble, was her question of ‘first importance’ – of all the nonsense! As though one nigger in a million would recognise the stone, or knew it existed, even. And those who did would be fat crawling rajas ready to fawn and applaud if she proposed painting the Taj Mahal red white and blue with her damned diamond on top. Still, she was showing more delicacy of feeling that I’d have given her credit for; well, I could set her mind at rest … if I wanted to. On reflection, I wasn’t sure about that. It was true, as she’d said, that Koh-i-Noor had been bad medicine only for men, from Aladdin to Shah Jehan, Nadir, old Runjeet, and that poor pimp Jawaheer – I could hear his death-screams yet, and shudder. But it hadn’t done Jeendan much good, either, and she was as female as they come … ‘Take it, Englishman’ – gad, talk about your Jubilee parties … No, I wouldn’t want it to be unlucky for our Vicky.

Don’t misunderstand; I ain’t superstitious either. But I’ve learned to be leery of the savage gods, and I’ll admit that the sight of that infernal gewgaw winking among the teacups had taken me flat aback … forty years and more … I could hear the tramp of the Khalsa again, rank on bearded rank pouring out through the Moochee Gate: ‘Wah Guru-ji! To Delhi! To London!’ … the thunder of guns and the hiss of rockets as the Dragoons came slashing through the smoke … old Paddy Gough in his white ‘fighting coat’, twisting his moustaches – ‘Oi nivver wuz bate, an’ Oi nivver will be bate!’ … a lean Pathan face under a tartan turban – ‘You know what they call this beauty? The Man Who Would Be King!’ … an Arabian Nights princess flaunting herself before her army like a nautch-dancer, mocking them … and defying them, half-naked and raging, sword in hand … coals glowing hideously beneath a gridiron … lovers hand in hand in an enchanted garden under a Punjab moon … a great river choked with bodies from bank to bank … a little boy in cloth of gold, the great diamond held aloft, blood running through his tiny fingers … ‘Koh-i-Noor! Koh-i-Noor! …’

The Queen and Elspeth were deep in talk over a great book of photographs of crowns and diadems and circlets, ‘for I know my weakness about jewellery, you see, and how it can lead me astray, but your taste, dear Rowena, is quite faultless … Now, if it were set so, among the fleurs-de-lys …’

I could see I wasn’t going to get a word in edgeways for hours, so I slid out for a smoke. And to remember.

I’d vowed never to go near India again after the Afghan fiasco of ’42, and might easily have kept my word but for Elspeth’s loose conduct. In those salad days, you see, she had to be forever flirting with anything in britches – not that I blame her, for she was a rare beauty, and I was often away, or ploughing with other heifers. But she shook her bouncers once too often, and at the wrong man: that foul nigger pirate Solomon who kidnapped her the year I took five for 12 against All-England, and a hell of a chase I had to win her back.fn1 I’ll set it down some day, provided the recounting don’t scare me into the grave; it’s a ghastly tale, about Brooke and the headhunting Borneo rovers, and how I only saved my skin (and Elspeth’s) by stallioning the mad black queen of Madagascar into a stupor. Quaint, isn’t it? The end of it was that we were rescued by the Anglo-French expedition that bombarded Tamitave in ’45, and we were all set for old England again, but the officious snirp who governed Mauritius takes one look at me and cries: ‘’Pon my soul, it’s Flashy, the Bayard of Afghanistan! How fortunate, just when it’s all hands to the pumps in the Punjab! You’re the very man; off you go and settle the Sikhs, and we’ll look after your missus.’ Or words to that effect.

I said I’d swim in blood first. I hadn’t retired on half pay just to be pitched into another war. But he was one of your wrath-of-God tyrants who won’t be gainsaid, and quoted Queen’s Regulations, and bullied me about Duty and Honour – and I was young then, and fagged out with tupping Ranavalona, and easily cowed. (I still am, beneath the bluster, as you may know from my memoirs, as fine a catalogue of honours won through knavery, cowardice, taking cover, and squealing for mercy as you’ll ever strike.) If I’d known what lay ahead I’d have seen him damned first – those words’ll be on my tombstone, so help me – but I didn’t, and it would have shot my hard-earned Afghan laurels all to pieces if I’d shirked, so I bowed to his instruction to proceed to India with all speed and report to the C-in-C, rot him. I consoled myself that there might be advantages to stopping abroad a while longer: I’d no news from home, you see, and it was possible that Mrs Leo Lade’s noble protector and that greasy bookie Tighe might still have their bruisers on the look-out for me – it’s damnable, the pickle a little harmless wenching and welching can land you in.3

So I bade Elspeth an exhausting farewell, and she clung to me on the dockside at Port Louis, bedewing my linen and casting sidelong glances at the moustachioed Frogs who were waiting to carry her home on their warship – hollo, thinks I, we’ll be calling the first one Marcel at this rate, and was about to speak to her sternly when she lifted those glorious blue eyes and gulped: ‘I was never so happy as in the forest, just you and me. Come safe back, my bonny jo, or my heart will break.’ And I felt such a pang, as she kissed me, and wanted to keep her by me forever, and to hell with India – and I watched her ship out of sight, long after the golden-haired figure waving from the rail had grown too small to see. God knows what she got up to with the Frogs, mind you.

I had hopes of a nice leisurely passage, to Calcutta for choice, so that whatever mischief there was with the Sikhs might be settled long before I got near the frontier, but the Cape mail-sloop arrived next day, and I was bowled up to Bombay in no time. And there, by the most hellish ill-luck, before I’d got the ghee-smell in my nostrils or even thought about finding a woman, I ran slap into old General Sale, whom I hadn’t seen since Afghanistan, and was the last man I wanted to meet just then.

In case you don’t know my journal of the Afghan disaster,fn2 I must tell you that I was one of that inglorious army which came out in ’42 a dam’ sight faster than it went in – what was left of it. I was one of the few survivors, and by glorious misunderstanding was hailed as the hero of the hour: it was mistakenly believed that I’d fought the bloodiest last-ditch action since Hastings – when in fact I’d been blubbering under a blanket – and when I came to in dock at Jallalabad, who should be at my bedside, misty with admiration, but the garrison commander, Fighting Bob Sale. He it was who had first trumpeted my supposed heroism to the world – so you may picture his emotion when here I was tooling up three years later, apparently thirsting for another slap at the paynim.

‘This is the finest thing!’ cries he, beaming. ‘Why, we’d thought you lost to us – restin’ on your laurels, what? I should ha’ known better! Sit down, sit down, my dear boy! Kya-hai, matey! Couldn’t keep away, you young dog! Wait till George Broadfoot sees you – oh, aye, he’s on the leash up yonder, and all the old crowd! Why, ’twill be like old times – except you’ll find Gough’s no Elphy Bey,4 what?’ He clapped me on the shoulder, fit to burst at the prospect of bloodshed, and added in a whisper they could have heard in Benares: ‘Kabul be damned – there’ll be no retreat from Lahore! Your health, Flashman.’

It was sickening, but I looked keen, and managed a groan of dismay when he admitted that the war hadn’t started yet, and might not at all if Hardinge, the new Governor-General, had his way. Right, thinks I, count me as one of the Hardinge Ring, but of course I begged Bob to tell me how the land lay, feigning great eagerness – in planning a campaign, you see, you must know where the safe billets are likely to be. So he did, and in setting it down I shall add much information which I came by later, so that you may see exactly how things were in the summer of ’45, and understand all that followed.

A word first, though. You’ll have heard it said that the British Empire was acquired in a fit of absence of mind – one of those smart Oscarish squibs that sounds well but is thoroughly fat-headed. Presence of mind, if you like – and countless other things, such as greed and Christianity, decency and villainy, policy and lunacy, deep design and blind chance, pride and trade, blunder and curiosity, passion, ignorance, chivalry and expediency, honest pursuit of right, and determination to keep the bloody Frogs out. And often as not, such things came tumbling together, and when the dust had settled, there we were, and who else was going to set things straight and feed the folk and guard the gate and dig the drains – oh, aye, and take the profit, by all means.

That’s what study and eye-witness have taught me, leastways, and perhaps I can prove it by describing what happened to me in ’45, in the bloodiest, shortest war ever fought in India, and the strangest, I think, of my whole life. You’ll find it contains all the Imperial ingredients I’ve listed – stay, though, for ‘Frogs’ read ‘Muslims’, and if you like, ‘Russians’ – and a few others you may not believe. When I’m done, you may not be much clearer on how the map of the world came to be one-fifth pink, but at least you should realise that it ain’t something to be summed up in an epigram. Absence of mind, my arse. We always knew what we were doing; we just didn’t always know how it would pan out.

First of all, you must do as Sale bade me, and look at the map. In ’45 John Company held Bengal and the Carnatic and the east coast, more or less, and was lord of the land up to the Sutlej, the frontier beyond which lay the Five Rivers country of the Sikhs, the Punjab.5 But things weren’t settled then as they are now; we were still shoring up our borders, and that north-west frontier was the weak point, as it still is. That way invasion had always come, from Afghanistan, the vanguard of a Mohammedan tide, countless millions strong, stretching back as far as the Mediterranean. And Russia. We’d tried to sit down in Afghanistan, as you know, and got a bloody nose, and while that had been avenged since, we weren’t venturing that way again. So it remained a perpetual threat to India and ourselves – and all that lay between was the Punjab, and the Sikhs.

You know something of them: tall, splendid fellows with uncut hair and beards, proud and exclusive as Jews, and well disliked, as clannish, easily recognised folk often are – the Muslims loathed them, the Hindoos distrusted them, and even today T. Atkins, while admiring them as stout fighters, would rather be brigaded with anyone else – excepting their cavalry, which you’d be glad of anywhere. For my money they were the most advanced people in India – well, they were only a sixth of the Punjab’s population, but they ruled the place, so there you are.