Полная версия

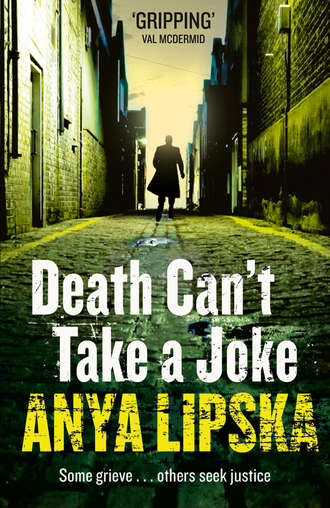

Death Can’t Take a Joke

After a good ten minutes, he heard Oskar crunching back across the gravel. A moment later he opened the driver’s side door and started to push a large sculpture of some kind up onto the seat, with much huffing and puffing.

‘Give me a hand, Janek!’

‘Can’t you put it in the back?’

‘This is easier.’

‘What the fuck is it meant to be anyway?’ asked Janusz once they’d manhandled the thing up onto the bench seat.

‘What does it look like?!’ Oskar’s tone was incredulous. ‘It’s a moo-eye, obviously.’ Hauling his chunky frame into the front seat, he slammed the van door and threaded the seat belt around their passenger.

Janusz peered at its profile. He could see now that it was a giant head – a clumsy reproduction of one of the monumental Easter Island sculptures, cast in a pale grey resin intended to resemble stone.

‘It’s moai, donkey-brain.’

‘Moo-eye – like I said!’ Oskar started the van. ‘She said she wanted something classical. How is a moo-eye not classical? They’re hundreds of thousands of years old!’ He shook his head. ‘Now she tells me she meant a naked lady.’

As they got closer to Walthamstow the traffic slowed and thickened. The sight of the huge, implacable stone face gazing out through the windscreen of a scruffy Transit van started to draw disbelieving stares from passers-by and appreciative blasts on the horn from fellow motorists.

Oskar lapped up the attention, returning the toots and scattering thumbs-ups left and right, while Janusz sat in silence, one hand spread across his face. The last straw came when Oskar wound down his window to receive a high five from a passing bus driver.

‘Let me out, Oskar,’ he growled. ‘I can walk to the gym from here. And give me a call if you hear anything interesting.’

He found Jim’s Gym open for business and packed with clients squeezing in a lunchtime workout. The faces were all male and for the most part either black, or Asian and bearded. The iron filings smell of sweat and testosterone filled the air like an unsettling background hum. Seeing Janusz, one of the older black guys, a regular called Wayne who sometimes came to the pub, set down the weights he’d been hefting and headed over. Wiping the sweat from his palms onto a towel, he offered his hand.

‘Terrible news about Jim,’ he said, eyes sorrowful, seeking Janusz’s gaze. They shook hands and spoke briefly, before Janusz continued towards the little office at the rear, where he’d sometimes come to pick up Jim on the way to the boozer.

But as he reached for the door handle, he felt himself engulfed by a surge of grief so powerful he had to steady himself against the doorjamb. This had happened more than once since he’d identified Jim’s body, every time it hit him – the dizzying realisation that he would never again see his mate’s face, nor hear that big laugh.

Inside, he was confronted by the sight of the deputy manager, a young black guy called Andre, sprawled in Jim’s chair, behind Jim’s desk, chatting and laughing into a mobile phone. Bad timing. Two strides took Janusz across the room and before the guy could even get to his feet he found the phone slapped out of his hand and across the room.

‘What the fuck, bruv?!’

‘Show some respect,’ said Janusz. ‘Jim’s not even buried yet. And who said you could take his desk?’

Andre jutted his chin out. ‘And who’s you to tell me I can’t, old man?’

A grim smile tugged at the side of Janusz’s mouth. ‘Haven’t you heard? I’m the new owner.’ No need to tell the guy that he’d already instructed his solicitor to transfer ownership of the gym to Marika.

Andre opened his mouth to speak, then shut it again. Seating himself on the desk, facing the kid, Janusz lit a cigar. Smoking in here was probably against the law, but with a murder rap hanging over him he figured he could take the risk. ‘I suppose you’ve had the cops down here already?’

‘Yeah, they was in, asking all this and that,’ said Andre, kissing his teeth.

Janusz suppressed an urgent desire to bitch-slap him. He raised his eyebrows. ‘Ask about me, did they?’

‘Yeah. Like did you and Jim ever have a fight, stuff like that.’ He gave Janusz an assessing look. ‘I told the feds, you might be big but if Jim wanted to he could’ve put you down –’ he mimed a right hook and a left uppercut, ‘– boof boof … no contest.’

‘You’re right about that,’ chuckled Janusz, leaning across him to tap ash into the wastepaper bin. ‘Listen. Since it looks like we’re going to be working together, I need to ask you some stuff.’

‘Sure,’ said Andre, although Janusz saw a guarded look come into his eyes.

‘Did you ever see Jim with a woman, other than his wife, I mean?’

A broad grin spread across Andre’s face, revealing what looked like – but almost certainly wasn’t – a diamond, set in one of his incisors. ‘You tellin’ me Jimbo had a bit of poon on the sly?’

Janusz shrugged, non-committal. It hadn’t escaped his attention that, on hearing the line of questioning, the guy had visibly relaxed. ‘Did he ever mention a girl called Varenka? Tall, blonde, good-looking – speaks with an Eastern European accent? Maybe she’s a member of the gym?’

‘We don’t get too many ladeeez in here,’ said Andre. ‘They might find themselves a bit too popular, if you get what I’m saying.’ He pumped his arms and hips back and forth, miming rough sex, before creasing up at his own joke.

Janusz bent to grind his cigar out on the waste bin, so that Andre couldn’t see the look in his eyes. By the time he’d straightened up, he was smiling. ‘Do me a favour and have a discreet ask around, would you? You know, I’m going to need someone to manage this place once we’ve got the funeral out of the way.’

‘Absolutely. I’ll get straight on it.’ Andre jumped to his feet, doing a passable impression of the young dynamic manager. ‘And don’t worry about things here – I’m all over it.’

Janusz’s gaze swept the office. ‘Where’s Jim’s laptop, by the way?’

Andre’s gaze wavered. ‘No idea, boss. All the gym records get kept on that old piece of junk,’ he used his chin to indicate a scuffed PC in the corner. ‘Like I told the feds, he took his laptop home most nights.’

Janusz knew that Marika had already checked at home and found no sign of it. Had this little punk grabbed the chance to get a free laptop? Or might there be something on the laptop to help solve the puzzle of Jim’s murder, information someone wanted to conceal and had, perhaps, paid good money to get their hands on? Again, Janusz saw Varenka, long legs scissored across the pavement, after she’d been struck by the bullet-headed man. What did she – or her assailant – have to do with Jim?

Janusz opened his wallet and handed Andre his card, followed by two twenties. ‘Send Marika a really nice bunch of flowers,’ he said. ‘With a message, offering sincere condolences from everyone at the gym.’

Eight

Kershaw began her second day on Murder Squad with a firm resolution: to make a real effort to get to know her fellow DCs. She was aware that elbowing her way onto the Fulford case probably hadn’t been the most diplomatic way for a newbie to introduce herself. The police force was a bit like the Army: okay, bonding with your fellow detectives might not make the difference between life and death, but she’d learned the hard way that being Billy-no-mates could make a tough job a hundred times harder.

So she was making tea for everyone in the galley kitchen off the main corridor, when she felt a hand slip round her waist. She stomped backwards with her heel, a purely reflex action that brought a yelp of protest. Whipping round, she found Ben’s chocolate-brown eyes screwed up in pain.

‘Fuck! Sorry, Ben – but you really shouldn’t have done that!’

He pulled a rueful grimace. ‘I almost forgot I’m dating the woman who came top of her unarmed combat class.’

‘Remember what we said? About trying to keep out of each other’s way at work?’ she said, turning back to the kettle.

‘Yeah, ‘course. I did make sure there was no one around before coming in,’ he said, rubbing his foot.

Why was he always so goddamn reasonable?

‘Well, it’s not a very good start.’ She was surprised at the vehemence in her own voice.

They’d agreed to keep their relationship quiet at work – neither of them fancied being the butt of banter or fresh meat for canteen gossip, but for Kershaw it went deeper than that. Ever since starting basic training, her strategy for survival in what was still largely a man’s world had been to cultivate a ‘one of the boys’ persona, which, having spent her formative years hanging out with her dad and his mates, came easily to her. But the strategy had a downside: it meant never getting involved with a work colleague.

She had hoped that, with Ben working in a different part of the building, they’d barely see each other. But now, she felt as though the barriers she’d erected between her public and private lives were crumbling – and she didn’t like the feeling one bit.

‘What are you even doing on this floor, anyway?’ she asked, glancing out through the half-open door.

‘I had to see Streaky about something. Oh, and I wanted to ask if I could kip at yours tonight? I’m seeing Jamie Ryan for a drink later and I’ve got an early start at Woolwich Coroners Court – your place is closer than mine.’

That got her attention. ‘Hannah Ryan’s Dad? Has there been a development?’

It was over a year now since a paedophile picked up eleven-year-old Hannah Ryan, who’d been born with Down’s Syndrome, during a trip to her local corner shop. He’d promised her a ride in a rowing boat at a nearby lakeside beauty spot called Hollow Ponds; instead, after sexually assaulting her, he tied a plastic bag round her neck and dumped her body in the lake. But Hannah survived. Ben, who’d been the investigating officer on the case, had shown Kershaw the casefile photo of Hannah before the attack – she could still see her trusting smile under a mop of curly red hair.

‘Nada.’ Ben shook his head. ‘You’d think somewhere between the corner shop and Hollow Ponds somebody would have seen them.’ He frowned at the floor. ‘Officially, the case is still open, but after this long? You and I know it’s dead as a doornail.’

Forensics had been unable to recover any DNA evidence, but one name kept coming up – Anthony Stride, a serial child sex offender who lived three streets away from the Ryans. When Hannah picked Stride out of a book of mugshots, a search warrant was granted and the police found evidence on his computer that he’d boasted about the attack under a pseudonym on a chat room used by abusers.

Kershaw remembered Ben’s jubilation when he’d told her the news. But when the case came to court – disaster. The defence barrister put the DC who’d searched Stride’s flat through the wringer, finally getting him to admit that he’d pulled up the search history on Stride’s PC and clicked through to the chat room. The computer should have been bagged and sent straight to the Computer Crime Unit where specially trained officers would have preserved and cloned the data before investigating it further. The cock-up allowed Stride’s barrister to plant the idea in the minds of jurors that the cops might have interfered with the crucial evidence. Next, cross-questioning Hannah via video link, he’d suggested that since Mr Stride and she were both regulars at the corner shop, she might have seen him there on a previous visit, thus sowing another seed of doubt. In his summing up, he had made much of the idea that, in the light of Hannah’s learning difficulties, it would be ‘all too understandable’ for her to confuse Stride with her real attacker. The jury deliberations took seven hours, but they’d eventually returned a ‘not guilty’ verdict. When the judge revealed that Stride had already served time for offences against young girls, there had been gasps on the jury benches and two female jurors had openly wept.

Kershaw had never seen Ben so rocked. Although he hadn’t been the Ryans’ official FLO – family liaison officer – he’d spent a lot of time with them and grown particularly close to Hannah’s Dad Jamie, a second-generation Irishman who ran the family haulage firm. Ben’s distress at what he saw as his failure to nail Stride so alarmed her that she had even tried – unsuccessfully – to persuade him to put in for counselling. Recently, he’d seemed to be getting back to the old Ben, so finding out that he was still seeing Jamie Ryan socially made her uneasy: getting personally involved in a case was never a good idea. She decided to broach the subject with him when they were properly alone.

For now, she just touched his arm lightly, by way of apology for her bad temper. ‘Of course you can stay. I’m on early turn tomorrow, so let yourself in. I’ll see you in the morning.’

Ten minutes later, she was in mid-chat with fellow DC Sophie, who sat at the desk opposite hers, when Streaky swaggered over.

‘Sorry to break up a good gossip, girls,’ he said.

Sophie bridled. ‘Actually, Sarge, I was just briefing Natalie on our most recent cases.’

‘Swapping knitting patterns more like,’ Streaky chuckled, pushing Kershaw’s paperwork aside to clear space on the desk for his substantial backside.

As Sophie’s face flamed red, Kershaw felt a mix of sympathy and amusement. She’d endured her fair share of Streaky’s sexist banter in the past, before coming to realise that it was all just part of his act. He’d actually admitted to her once, at the end of a particularly long night in the Drunken Monkey, that women made far better detectives than men; even if he’d gone on to spoil things by adding that their superior observational and deductive skills were down to them ‘always being on the lookout for a husband’.

‘Sophie was briefing me on the local drug gangs, Sarge,’ said Kershaw, shooting a supportive look her way. ‘In case Jim Fulford’s murder does turn out to have been a junkie mugging.’

‘Not that you’re going to have any time to spare for the Fulford case, DC Kershaw,’ said Streaky, pointing a rolled- up printout at her. ‘Docklands nick has just told me that you’ve taken it upon yourself to identify some mystery roof diver?’

‘Ah, yes, I meant to talk to you about that, Sarge.’

‘You do know we investigate murders here, don’t you? Which if memory serves, tend to be defined as deliberate slayings at the hands of a third party?’

‘Yes, Sarge, it’s just that I was first on the scene, and since I did all the initial investigations, I thought it made sense for me to finish the job.’ When she said it out loud like that, it struck her how head-girlish it sounded. And she had to admit that, now she had a murder case to get her teeth into, the mystery jumper could prove to be a major in- convenience.

Streaky unrolled the printout with a magisterial frown. ‘Let me see … no identification of any kind on the body … no tattoos, birthmarks or unusual dentistry … no missing persons report fitting the description … number of people working in Canary Wharf tower 7,653 …’ After shooting her a meaningful look, he turned to the second page. ‘Oh, I do beg your pardon! If I implied that there were no clues to the identity of the deceased, I was wrong.’

By now, it was Sophie who was sneaking Kershaw the sympathetic looks.

‘PC Percy Plod found a zloty in the gutter!’ Streaky scooted the document onto Kershaw’s desk. ‘With a red-hot lead like that I should think you’ll have the case solved by the end of your shift. It’s a shame you’ll have your hands full, because I was going to give you some more action points in the Fulford case.’ Getting to his feet, he tucked an errant shirt tail back into his trousers, and strode off.

Nine

Janusz was kneading bread dough on his kitchen worktop when his mobile sounded.

‘Czesc, Oskar,’ he grunted, holding the phone to his ear with his thumb and index finger so as not to douse it in flour.

‘Ask me what I found out about your friend with the Land Rover Discovery.’

‘I haven’t got time to play twenty questions,’ said Janusz. ‘I’m up to my elbows in sourdough.’

Oskar made kissing noises down the phone. ‘You know, Janek, you’d make someone a lovely wife. I bet you’re wearing a really cute apron, too.’ Then, adopting a concerned voice: ‘You do know that I’ll always be there for you, don’t you?’

‘What?’

‘When you finally decide to come out of the closet.’

Janusz held the phone away from his ear as Oskar roared with laughter. ‘Actually, I’m cooking dinner for Kasia tonight, turniphead,’ he said, one side of his mouth lifting in a private smile.

‘Janek, Janek,’ said Oskar. ‘Are you still kidding yourself that she’s going to leave that dupek Steve?’

Janusz leaned against the worktop and let Oskar carry on in this vein for a while. The worst of it was, he knew in his heart of hearts that his mate was probably right. The affair with Kasia had been going on for almost two years now yet she showed no sign of ending her marriage to her lazy, worthless husband.

‘Spare me the relationship counselling, Oskar,’ growled Janusz. ‘Just tell me what you’ve got.’

‘Keep your hair on, kolego, I was getting to that,’ said Oskar. ‘I dropped in on my mate, Marek, the one who owns a Polski sklep on Hoe Street? You should go there – he sells the best wiejska in London. And his rolmopsy …’

‘Oskar!’

‘Okay, okay. Anyway, it turns out that he knows the guy in the Discovery, the one you saw with that gorgeous bird!’

‘What does he know about him?’

‘He’s Romanian, grew up there when that kutas Ceausescu ran the place. But he managed to get out and went to live in Poland after Solidarity got in – Marek says his mother was Polish.’

That made sense, thought Janusz. Poland had been the first country to throw off communist rule in 1989, making it a magnet for people escaping Soviet-backed regimes all over Eastern Europe.

‘Does Marek know how the guy makes his money?’

‘Tak. He has business interests in Poland, Ukraine, some of the other ex-Kommi states,’ said Oskar. ‘Marek just invested some cash with him actually – he says he’s making a packet.’

‘Shady business?’ asked Janusz.

‘No! He says it’s all totally above board.’

Janusz just grunted. Some people didn’t ask too many questions so long as the rate of return was attractive.

‘Anyway, sisterfucker, listen to this,’ said Oskar. ‘Marek sees the Romanian going to some Turkish café opposite his shop in Hoe Street, twice a week, to drink coffee with the owner.’

Janusz had never had any dealings with London’s Turks, who kept themselves pretty much to themselves, but during the recent riots they’d won his grudging admiration. While the cops had stood by, helpless and outnumbered, as lowlifes looted and torched his local shops, further north in Green Lanes the Turks had lined up to defend their businesses armed with hard stares and baseball bats. When the dust had settled, theirs were the only shopfronts that didn’t require the attention of emergency glaziers.

‘And the girl? Does she go along to these meetings?’

‘Sometimes. But Marek says he’s always there – four o’clock, Thursdays and Fridays, regular as clockwork.’

Marek sounded like a nosy bastard to Janusz. He checked his watch: it was Thursday and just after three. Plenty of time to get up there and back in time to cook dinner.

Janusz still had no idea of the precise nature of the relationship between the girl Varenka and the Romanian. She certainly wouldn’t be the first girl to settle for an older, uglier lover in return for a luxurious life. But was he also her pimp? The scene Janusz had witnessed in Hoe Street, which had ended with the bastard assaulting her, suggested that was a strong possibility.

‘Did you get the name of this Romanian?’

He heard Oskar fumbling with a bit of paper. ‘Barbu Romescu.’

‘You didn’t let Marek know this was anything to do with Jim?’

‘Of course not, Janek! I just dropped into the conversation that I’d seen this seksowna blonde girl getting into a fancy black 4X4 in Hoe Street. You know, man talk.’

‘Not bad. Maybe you’re not as bat-brained as you look.’

‘I was thinking,’ Oskar’s voice became conspiratorial, tinged with suppressed excitement, ‘I could park the van near the café, like I was doing deliveries, and when the Romanian comes out, tail him to his hideaway.’

Janusz grinned at the idea of Oskar and his old crock of a van with the squealing fan belt shadowing anyone undetected. ‘I tell you what, kolego, here’s the best thing you can do. Take Marek out for a drink. Drop into the conversation that you have a mate who’s come into a pile of money and who is looking for investments paying a good return.’

Right after he’d hung up, the message waiting sign started flashing on his phone. It was a voicemail from Kasia.

‘Janek, darling. Please don’t hate me but I can’t make it tonight. We have so many late bookings for extensions, I’m going to have to stay here and help out. I’m really sorry. I’ll call again later and we can rebook? I love you, misiaczku.’

Janusz flung his phone down, sending up a dust cloud of flour, where it lay like an alien spacecraft crashed in a snowdrift. This wasn’t the first time Kasia had stood him up lately. She was always protesting that he was the love of her life, but these days her burgeoning nail bar business and inconvenient husband left barely any time for him. When she’d left her job as a pole dancer, Janusz had hoped that she might move on from Steve, too, but on the subject of her marriage her position was unwavering: as a devout Catholic, she said, she couldn’t countenance a divorce.

Staring at the sourdough, he contemplated binning it, but then resumed his kneading. It felt therapeutic, slamming the dough into the worktop. The cat, who was curled up on a kitchen chair cleaning himself, broke off from his ministrations to gaze up at Janusz.

‘You probably won’t see it this way, Copetka,’ he told him, ‘but when the vet took your nuts away, he saved you a world of trouble.’

Janusz arrived in Walthamstow ten minutes ahead of the Romanian’s scheduled meeting time. He bought a half of lager in Hoe Street’s last surviving pub and stationed himself in the window, almost directly opposite the Pasha Café, which had a sign advertising ‘Cakes, Shakes and Shisha’. And sure enough, even on this chilly day, there were two dark-skinned men seated at one of the pavement tables chatting and smoking shisha pipes beneath a plastic canopy. Janusz remembered reading somewhere that an hour spent smoking tobacco this way was the equivalent of getting through 100 cigarettes. Lucky bastards, he thought, cursing the smoking ban.

At two minutes to four, the black Discovery pulled up right outside the café and the bullet-headed man climbed out of the driver’s seat – no chauffeur today. He bent to retrieve something from the rear seat, a manbag, from the look of it, then turned, giving Janusz a view of short-clipped hair, a muscled back under a well-cut jacket, before heading for the café entrance. Janusz was just thinking he’d have to wait till the guy came out again for a good look at his face when, at the threshold, he turned to aim his key fob at the 4X4. It took barely a second – but long enough for Janusz to take a mental snapshot. The thing that caught his attention was a curious scar running down the side of his face. Reaching from temple to jaw, it looked too wide to have been carved by a blade, and yet unusually regular for a burn.

Janusz took a slug of lager, aware of a pulse starting to thrum in his throat. He’d seen his type before. His bearing, the way he walked and held himself, revealed more accurately than any psychiatrist’s report what kind of man he was: someone who saw other people as tools to achieve his ends – or as obstacles to be neutralised.