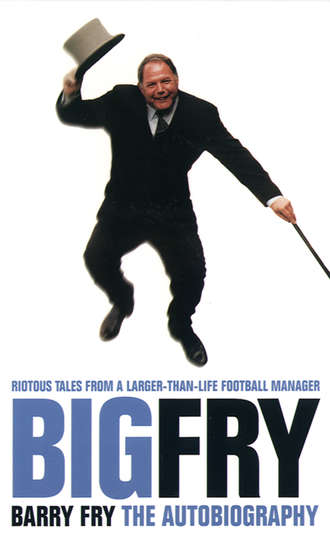

Полная версия

Big Fry: Barry Fry: The Autobiography

Another dream was fulfilled when, at the age of 16, I was picked for Manchester United reserves. The fixture list could not have been kinder if I had compiled it myself, because I made my debut at no other venue than Molineux, home of Wolverhampton Wanderers. I don’t know whether my failure to score was down to nerves, inability or a lack of desire to hurt my favourite club, but we won anyway. Before I was 17 I had played a dozen reserve games which, at that time at Manchester United, was almost an achievement of the impossible. One of the games in which I played was a night match at Anfield, where I was given the friendly greeting as I stepped off the team coach of spit in my face accompanied by someone shouting, ‘Piss off, Fry!’ It was a daunting experience for one so young. I wondered how the agitant even knew my name. At the time it slaughtered me, yet it taught me what to expect. First the Italians, then the Scousers … there is another side to football. So often there are examples of abnormal behaviour brought on by the passion which the game engenders. In no other sphere of life can there be such a collective will to win.

One March day in 1962, a month before my 17th birthday, Matt Busby called me into his office.

‘You have done brilliant, son. The whole staff are very pleased with your progress at Old Trafford and I have decided to offer you a two-year professional contract.’

He added that he did not want me to worry over whether or not I would be taken on and that he wished to give me advance notice of his intentions. This was a lovely stroke and, to an extent, a relief because so many kids, myself included, were wondering what might become of them. The signing of this contract did not mean much in monetary terms. There was a few quid more, but the maximum wage of £20 a week was in place then and I was to receive £12 8s 0d (£12.40) and £8 in the summer. At the time Matt was writing a column for the Manchester Evening News Pink and when we returned from Zurich after winning that second tournament trophy he wrote that, in Barry Fry, United had on their playing staff the northern Jimmy Greaves. I had been scoring a lot of goals, right enough, and I had made the most progress of all the apprentices who had joined at the same time. My big moment had arrived.

United were still in the process of rebuilding after the devastation and heartbreak of the 1958 Munich air disaster. On that dreadful day I had gone home from school to hear the breaking of the news of the tragedy on the radio. The newscaster had barely got the words out of his mouth before I burst into tears. Like many others, I cried all day and night and for days afterwards. Before United had travelled to Germany they played in London on the Saturday and won by a big margin with a sensational performance. Having been to Wembley so many times I had been privileged to see Duncan Edwards, Tommy Taylor and Roger Byrne and I had all their autographs. It was almost as if I knew this trio who lost their lives personally. I was not a Manchester United supporter then, but I have always passionately supported England and those who played for England. The crash had a profound effect upon me.

Everybody in the country, and a lot of countries throughout the world, felt very sorry for Manchester United. When they played Bolton Wanderers in the FA Cup Final that year, there was almost universal support for them. I was in the crowd at Wembley and watched as they lost 2–0 to a couple of Nat Lofthouse strikes. Jimmy Murphy had done a brilliant job in getting them there. Matt Busby was practically at death’s door in hospital and Jimmy had everything to sort out, not least the immediate rebuilding of the team. It was an achievement in itself just to have got them to Wembley.

When, two years later, I walked into Old Trafford the pall of Munich was still hanging over the place. Jimmy, Joe Armstrong and John Aston were always speaking with warmth about the players who were lost out there; how genuine and wonderful they were as people as well as footballers. They always emphasised that. The older players like Bobby Charlton, Harry Gregg and Bill Foulkes simply would not talk about Munich. It was too painful. A funny atmosphere was created whenever Munich was mentioned and it became almost a taboo subject within the club. The hurt was just too deep. In Jimmy Murphy’s dealings with the older apprentices and the first-year kids, however, he would use Munich as an illustration of how triumph could overcome adversity. He was great for Manchester United. With his aloofness and the tremendous respect he was shown by everybody, the manager, Matt Busby, was always the boss while Jimmy was the one filled with fire and passion. They were a terrific team. Busby didn’t hand out many roastings but when he did you knew full well that you had been told off. Jimmy, on the other hand, was always sounding off. He would pack the skip for an away trip and there would always be a bottle of scotch stashed in between the freshly-laundered shirts, shorts and socks. I once witnessed him take a swig during his half-time team talk and shower all the players as he tried to emphasize a point he was making. Jimmy was the Welsh team manager at this time and he spoke in glowing terms about the country and his admiration for the players, particularly Cliff Jones and John Charles. Cliff was the greatest winger out there, known and universally admired for his spectacular diving headers. I played with him later at Bedford Town and I could relate to him because I had heard so many stories about him. Two of us would converge upon him in training as he flew in from the wing and he would simply and effectively knock us both out of the way as he went through in barnstorming fashion. He was only little, but very strong. He would have made a great jockey.

When I had played 15 or so games for Manchester United reserves I thought I had truly arrived. I was a professional now, and instead of going in at nine o’clock, I sauntered in at ten o’clock or half past. There would be training for an hour and a half and, after 12.30, you would have nothing to do for the rest of the afternoon. The routine for the older lads was to go to the races at Haydock, the now-defunct Manchester, York or Chester and, unfortunately, it became a regular occurrence for me to jump into their cars and go along with them.

My first-year digs, in which Mike Lorimer had a room to himself and I shared with Eamon Dunphy, were with Mrs Scott, but when I returned from my home in Bedford to renew the arrangement, having failed to write to her or telephone in the summer, I knocked on the door expecting to be greeted with open arms. This was far from the case. Unfortunately I had forgotten my manners. She rasped: ‘What are you doing here?’ I told her that I was back and ready for the new season only to be informed that someone had taken my place. I rang Joe Armstrong, who ticked me off big time. I was a bit naive about the ways of the world and, apparently, I should have sent her a cheque. As far as I was concerned, though, the club paid for the accommodation; I had never dealt with money. It was all a bit strange.

My room-mate Eamon, who had played for the Republic of Ireland schoolboys when I played for England schoolboys in a 2–2 draw in Dublin, was everything I wasn’t. For a start, he was intelligent. He had a healthy understanding of religion and politics and showed me a facet of life which I never knew existed when he came home with me to Bedford one weekend. On the Sunday morning he was up at the crack of dawn to attend mass at 7am. Eamon was able to talk authoritatively on a whole spectrum of subjects about which I knew nothing, yet his cerebral dexterity got him into a lot of trouble at Old Trafford. He would get on people’s nerves and, small though he was, he ended up in many a fight. All hell broke loose one day when he made a snide comment to the goalkeeper Harry Gregg, who was from Northern Ireland. Harry, a huge man, lifted him eight feet into the air and was clearly going to punch his lights out. Now, I see this and go running over from the five-a-side game in which I am involved to rescue the situation. King Kong could not be humoured. This time he lifted us both to the same height, one in each hand, and crashed our heads together with such force that we both saw stars.

Eamon’s trouble was that he had an opinion on everything and almost always expressed it. There are at least some things I think which I like to keep to myself, but not him. What he believed he could not hold back and this led to further confrontation with Wilf McGuinness. Worse, it led me into confrontation with Wilf McGuinness. He and I must have had four fights, and each time they had nothing to do with the combatants and everything to do with Eamon Dunphy. It was always a case of him sending McGuinness, who was a tough guy, smashing into the advertising boards around the five-a-side pitch or uttering some obscenity in his direction. I would go in to sort out the ensuing altercation and it would go up between the two innocent parties. It got to a stage where McGuinness said: ‘I want to see you, Fry. Upstairs.’ Off we went, just the two of us, and we proceeded to batter hell out of each other. When it was over we wondered where it had all started in the first place. We both said that neither of us had a problem with the other, determined that Dunphy was the root cause and shook hands at the very moment that we espied the culprit walking over the bridge with his arm around a tasty-looking bird.

Myself and Wilf, a great character who had the misfortune to suffer one of the worst broken legs the game has ever seen, became mates. He was another with a real passion for the club.

Saddled with the problem of being housed for my second season, I became aware that Dunphy had been as ignorant as I and was in the same situation. Joe Armstrong said that Bobby Charlton, who lived in Stretford, was getting married and was leaving his digs with Mr and Mrs Jim Davenport. I would take his place there in a fortnight’s time but, meanwhile, was to share temporary accommodation with Dunphy next door to another Irish lad, Hugh Curran. At the Davenports I was joined by Ken Morton, who had played for England schoolboys, and Denis Walker, an older pro who knew everything. They were good days. I had my first car from Jim, who worked on the railways and who I always called ‘The Governor’. Now we were within five minutes’ walking distance of Old Trafford, just down the back alley and over the bridge. You didn’t have to get up so early. I had had lots of driving lessons and the day dawned when Jim came to change his car for a better one. He said that he wasn’t getting much from the garage for his, a cream Hillman Hunter, and that I could buy it if I fancied it. We did a deal on the never-never and he was so kind that I don’t think I ever paid for the car and he never mentioned it. I passed my driving test – at just the ninth attempt. Every time I failed it was for a different reason and I could never understand it. I hadn’t killed anybody; nobody had even suffered a life-threatening injury. I drove the car to Bedford and back many times without incident and, in those pre-motorway days, it would take ages all the way down the A6. Mrs Davenport took a keen interest in my progress and every time the car pulled up outside her house after a test she would look out of the window and question whether I had passed by means of a thumb’s up and an expectant look on her beaming face. I would return the thumb’s up sign and slowly turn it into a thumb’s down and she would say: ‘Oh no, not again. Why this time?’ She would be more disappointed than I was.

As the time was approaching when I would take my test for the sixth time I was very anxious and I asked the lads for some general tips and hints. Bobby Charlton came up with what sounded like a bright idea. ‘You know what you should do Baz,’ he said, ‘you should wear your Manchester United blazer.’ To impress the examiner further, I even put on my club tie. There was no way I could fail. I drove well and after 20 minutes we pulled into a layby and I was oozing confidence when he began asking questions about the Highway Code. I felt that I had got them all right and was crestfallen when he uttered those immortal words: ‘Mr Fry, I am afraid that you have failed to reach the required standard.’ With that, he got out of the car and as he was closing the door he bent down and added: ‘By the way, I’m a Manchester City supporter.’ It caused a riot of laughter when I related this at The Cliff training ground the following day with Bobby saying to me, ‘Barry, you must be the unluckiest guy walking.’

In the early hours of one morning I was awakened by a severe bout of coughing followed by a heavy thud. Mrs Davenport was on the floor, covered in blood, and she could not be attended by Jim, who was working a night shift. I called the doctor and her daughter, Sylvia, and she was diagnosed as having cancer. Her death soon afterwards was the first I had to cope with and it was very difficult. You become very close to those with whom you live and while Sylvia was kind enough to offer alternative accommodation to Ken Morton and myself, I did not like leaving The Governor on his own. Some time later I read that he had been killed, hit by a train on the railway for which he had worked for over 40 years.

It has been a lifetime regret that, as a footballer, I never fulfilled my promise – the has-been that never was. Although I had this great ability and started at the top with England schoolboys and Manchester United, I did not have a career. As soon as I signed professional forms, I went the wrong way. Those trips to the racecourse would be followed by a meal, then an outing to one of the local dog tracks at Salford, White City and Belle Vue. I was bitten deeply by the gambling bug and a further distraction was the Manchester night life. The next port of call after the greyhounds would be one of the night clubs and life became a merry-go-round of these glamorous playgrounds.

Noel Cantwell, who had joined Manchester United from West Ham in time for the 1963 FA Cup Final, arrived as the kind of philosopher and deep thinker about the game which was the trademark of players brought up in the Upton Park academy. He could not believe how off-the-cuff things were at Old Trafford. The essence, and often the sum total, of Matt Busby’s team talks would be: ‘We are better than them, go and express yourselves,’ whereas Noel had been accustomed to long tactical debates. United went into this Wembley final against Leicester City, with Cantwell the captain, as underdogs, yet emerged emphatic 3–1 winners. I was with the party, enjoying the sumptuous five-star hotel treatment before the game, and the atmosphere on the return train journey to Manchester was electric. A big card school was soon convened by Maurice Setters and others and my penchant for gambling, which by now was almost compulsive, was very much to the fore. We were playing brag, a game in which money is won and lost in the blink of an eye, and my stake was a fiver blind. Anybody who knows the game will tell you that it takes either nerves of steel or a suicidal tendency to strike so big a wager in that fashion. It was neither to me. I was 18 and had plenty of money with nothing to spend it on. I had saved everything for a couple of years, my digs were paid for, I never went out. For two years I dedicated myself to becoming a professional footballer; for the next two years I came dangerously close to careering off the rails. The warning signs were there. Instead of reading the national newspaper back pages and all the football coverage as I had so far done, I began taking the Sporting Life every day instead. It was not long before I was interested not only in what was running that day but what was running the following day as well. You don’t realise it at the time, but it soon becomes an obsession. At The Cliff you only had to look over the wall and you could see the horses at Manchester racecourse. One of the problems as a professional footballer is that you have too much time on your hands and you have to do something. I did gambling. At the time it was something I enjoyed greatly. I had no responsibilities and it didn’t matter if I did my bollocks. There would be two carloads of players going to the races and from there the rest would go home whereas I would head for the dogs, perhaps seeing Alan Ball, who was a regular at the Salford track.

One day I was waiting at the bus stop outside Old Trafford and Matt Busby drew up in his car. He asked me where I was going and when I told him that my destination was Manchester races he said: ‘Jump in.’ I had been having treatment for an injury and the other lads had gone on ahead of me.

‘Do you like racing?’ he asked me.

I told him I loved it.

‘Listen, son,’ he said, ‘it’s like women and it’s like drink. It is fine in moderation, but don’t ever let it get to grips with you.’

It was the best bit of advice anyone had ever given to me … and I took no notice whatsoever.

Since then I have seen so many players who have been paid millions of pounds end up without a pot to piss in. I never had a million pounds to start with, but all through my life gambling has cost me to some extent. Gus Demmy was the top bookmaker in Manchester and I would see him at all the various meetings. I got to know him quite well and in the end he gave me a job chalking up the prices in his main betting office in the afternoons. I never made any wages because I used to do them all behind the counter, but I was in my element. In those days I had a Post Office account from which I was making withdrawals on a regular basis to fund my gambling. It soon whittled down from a few thousand to nothing and it was a frightening experience to look at the opening and closing balances. Even if I won, it was a case of loaning the money from the bookmakers for just a couple of days before I gave it back to them. But I got a great buzz out of it.

When we were abroad with United we used to get a daily allowance of £10, so you only needed to be away for 10 days to have a tidy sum to look forward to. They were in a different league with that kind of perk. The trouble is that once you leave, everything is an anticlimax. Looking back, it is true to say that I stopped working at my game. I ceased to focus. I still played in the reserves, but other, younger players were leapfrogging me. One such player was Willie Anderson. Another was George Best, who went straight from the A team into the first team.

George and I got along great and still do to this day. There have been various occasions on which he has come to my rescue in times of strife and who would have thought that would be the case when as a slight, shy boy he walked into Old Trafford a year behind me? The omens were not very good for George when he became homesick after a day, went back to Belfast and Joe Armstrong pursued him and dragged him back, yet he was the most naturally gifted footballer I had ever laid eyes upon. Despite his lack of size and weight he would beat people for fun in training, which infuriated some players. They would shout: ‘Cross it, get the ball across …’ and they would moan and groan when he didn’t. The boss and Jimmy Murphy would tell them to leave him alone, adding that he would learn with time when to cross. More fuel would be poured onto the fires of his detractors when he would beat four men in a spellbinding mazy dribble, go back for more and then lose the ball. What was clear from the outset was that George had the heart of a lion. For a wiry little kid he had this great strength and determination. He tackled like a full-back. There were some real full-blooded full-backs around in those days, like Roy Hartle and Tommy Banks, but even they would have been proud of the challenges delivered by George. It was like being hit by a double-decker bus. He was a genius. I loved him. His terrible shyness meant that he needed a bit more looking after than most and I was more than happy to help in that direction.

I had been going out with a girl called Judith Fish, which was something of a laugh in itself. Fish meets Fry! If we had got married I don’t think that either of us could have resisted the temptation for her to carry a double-barrelled surname, which is the current vogue for women. Judith’s father Tom, a local big businessman, was a rabid Manchester United fan and I got Denis Law to go along and cut the tape when he opened a garage. All the apprentices were given two complimentary tickets for matches and those not required for friends and family were sold to Tom. It was a few extra quid for the lads and no harm was done. I would buy George’s complimentaries and pass them on to Tom. As everyone knows, George became a star overnight and rightly so. The beauty about George is that he has had so many bad things written and said about him – he can do 99 good things for people and one bad thing will have him on the front, back and middle pages of every newspaper – that while the temptation must have been to lay low he has kept smiling through. He has been brilliant to me, always keeping in touch despite his having reached the dizzy heights and me having never got off the ground in terms of playing careers. The only sad thing about him is his having packed up at the age of 27.

George’s career did not really start to blossom until after I had left Old Trafford in the 1964/65 season. It was to be three more years until their famous victory in the European Cup and he entered the realms of superstardom as ‘El Beatle’. By this time I had gone into management and he was in that surreal world of agents, advisers and hangers-on which was brought about as much by his inability to say no to anyone as people wanting to be associated with him.

To demonstrate just how different class he was, my cousins Karen and Pauline Miller were obsessed, like thousands of other girls, with George and wanted to meet him. Manchester United were playing a night match at Luton at the height of his popularity and, even though I hadn’t seen him for a few years, he greeted me warmly when I went into their dressing room and agreed to see the girls after the game. The lads, meanwhile, were saying: ‘Hey Barry, you still backing those f***ing losers?’ and having a laugh. That’s football for you. George emerged later and greeted Karen and Pauline, who haven’t washed their hands since.

The parting of the ways for me at Old Trafford was, indeed, a sad moment. Just as he had done in much happier circumstances a couple of years previously, Matt Busby called me into his office at the end of April 1965, with my contract due to expire at the end of June. I was 19 and I honestly thought he was going to offer me another contract. All players do. One of the strange things about football is that even if you are a crap player, or even a decent player whose game has turned to crap, you cannot see it yourself. You always think you are better than you are in reality.

‘Barry,’ he said. ‘You haven’t progressed as much as we would have liked you to have done. Other players who were not as advanced as you have now overtaken you.’

He added that Bolton Wanderers had made an approach for me.

‘We won’t charge any money,’ Matt said. ‘We will give you a free transfer so that you can get yourself looked after.’

He urged me to go home and think about it for a day or two, putting me under no pressure, and the following day I went to see Noel Cantwell, the club captain. I told him what had happened and he said: ‘Don’t go to Bolton, go to Southend. I know the manager there, Ted Fenton, who used to be my boss at West Ham. I’ll get in touch with him and give you a glowing report.’ This confused me even more and for a few days I was in a daze. For the first time in my life I felt a failure. Although Matt had not said as much, I felt that Manchester United no longer wanted me and the fact that he was allowing me to talk to other clubs only reinforced this viewpoint.

George Martin, the chief scout at Bolton, came round to my digs and told me that they had permission to talk to me with a view to joining them. United, he said, were going to release me anyway. They were words which felt like daggers through my heart.

On many occasions I have been offered big money by the media to criticise Matt Busby, but there is no way I would ever do that. Matt Busby is not the reason I failed. Barry Fry is the reason I failed. All Matt did was to give me good advice and the opportunity to join the biggest club in the world. Lots of players have got chips on their shoulders when they leave clubs, because they feel they have more ability than those they have left behind. Many are right to hold that view. But those who remain are invariably more dedicated, more focused. Such players are often bitter and twisted. Not me. I look in the mirror and see a man who let himself down, not one who was let down by others.