Полная версия

Charles: Victim or villain?

Dedication

To Jane

Contents

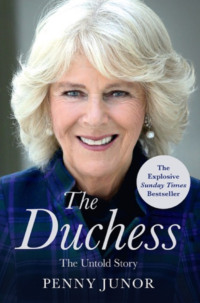

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

1 Death of a Princess

2 A Nation Mourns

3 The Young Prince

4 The Discovery of Diana

5 The Fairytale Fiancée

6 The Honeymoon Period

7 A State of Mind

8 The Offices of a Prince

9 Marriage and the Media: After Morton

10 The Beginning of the End

11 Camillagate

12 Difficulties at Work

13 Organic Highgrove

14 The Prince’s People

15 ‘Mrs PB’

16 Visions of the Monarchy

17 Charles and Camilla

18 Victim or Villain?

Epilogue

Index

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

Opinion polls suggest that the reputation of the Prince of Wales is beginning to recover after the emotional turmoil of Diana’s death in August 1997. It had not been good before she died, largely because of his relationship with Camilla Parker Bowles, but in the days that followed the fatal crash it plumbed new depths, as the nation’s anger at the loss of the Princess it loved so dearly turned on the monarchy and, more particularly, the heir to the throne. When Diana’s brother, Charles Spencer, gave his address at her funeral, and said that he would rescue her sons from the clutches of the Royal Family, the nation cheered – literally – as his voice was relayed to those inside and outside Westminster Abbey.

The Prince’s new-found popularity is no doubt gratifying, and has much to do with the way he has been seen to care for his children in the wake of their mother’s death. A significant percentage of the population would even sanction his marriage to Camilla Parker Bowles. However, a popular misconception undermines this growing acceptance: the belief that the Prince always loved Camilla and made no attempt during his years of marriage to Diana to shut his mistress out of his life.

Few would deny that it takes two to make a marriage, and two to break it. Yet millions of people the world over have been led to believe that the Prince of Wales destroyed his marriage, alone and unaided, because of his obsession with Mrs Parker Bowles. In 1992, Andrew Morton told Diana’s story – one side of the story – in a book that brought about the end of the ‘fairytale’ marriage. Diana – Her True Story, which was reissued after Diana’s death and renamed In Her Own Words, gave a picture of Charles and Diana’s life together and the part his mistress had to play in it, which is not quite what those who knew both Charles and Diana best remember.

So far, no one has attempted to tell the complete story. While Diana was alive the Prince would never allow it because he didn’t want to hurt either her or their children. In all their years together and apart, and despite intense provocation, he never spoke ill of her in any way. Now that she is dead Charles is even more determined that he will not defend himself and that history alone shall be his judge. If that means waiting until he is long dead, so be it. He has no qualms about meeting his maker. The evidence to support what really happened – letters, diaries, tapes, medical records, which explain the true nature of the relationship – is under lock and key at the Royal Family Archive at Windsor. One day in the future, when they are released, the whole truth will be told.

In the meantime, a number of his family and friends feel he has suffered enough and believe there should be some attempt to correct at least some of the misconceptions.

Diana said some terrible things about Charles, which she later regretted quite bitterly. Not, however, before millions of people were led to believe that she was taken ‘like a lamb to the slaughter’ into a loveless union, in order to produce an heir for a man who had no intention of honouring his marriage vows. On the strength of Diana’s words, there are many who believe that he carried on an affair with his mistress throughout his marriage, even sleeping with her the night before his wedding and resuming their affair immediately after the honeymoon. They believe Charles was a cold and insensitive husband and a cold and insensitive father, who only now, after Diana’s death, is beginning to show a little affection for his children. Some people even blame Charles for Diana’s death. And, because Diana said so on prime time television, in an interview for ‘Panorama’ in 1995, many believe he is not fit to be king.

It is hard to imagine Prince Charles’s emotions as he walked behind Diana’s cortège that September morning, their sons by his side, bravely fighting back their tears. Never had there been such public outpourings of love and grief for someone so few had ever met. The world had loved her, admired her, worshipped her. He had rejected her, divorced her. Why?

Charles: Victim or Villain? tries to explain what really happened in that marriage; to give a more objective view than Diana’s, and reveal more clearly than ever before the part Camilla Parker Bowles played in it. Not for the sake of the Prince of Wales – who, like Diana, is not entirely blameless – but for the sake of the millions of people who have lived through this royal soap opera and have never had an alternative account of what happened on which to form a judgement for themselves. At the moment there is only Diana’s account, which is flawed and inevitably partial, as even her friends will admit in private.

It is an attempt to describe why Charles married Diana, what life was like for them both, and what went so badly wrong that she felt compelled to tell the world and take very public revenge on her husband. What possessed Charles to confess his infidelity on camera – as he did to Jonathan Dimbleby in a two-and-a-half-hour documentary about his life in June 1994 – and how did he feel when he faced the public after the embarrassment of the Camillagate tapes that exposed his late-night ramblings on the telephone to his mistress?

The two young princes, William and Harry, have lived through it all – the embarrassment, the affairs, the divorce and, finally, the traumatic death of their mother. How are they faring as a family today? What do they think of Mrs Parker Bowles? What is the future likely to hold for them all?

This is a portrait of the Prince of Wales at fifty. A very private man, with a public role, in an intrusive media world. A single parent and future king, a man emotionally handcuffed by his upbringing and damaged by the failure of his marriage. He is a man who inspires great love and loyalty, but a man of contradictions. He can be the greatest company or the most sombre; the kindest, most considerate of human beings or the most selfish. He has warmth and charisma, and a wicked sense of fun but, when he doesn’t get what he wants, a fearsome temper that in fifty years he has never learnt to control. He is a man who cares about the disadvantaged, and the sick and dying, no less than the planet we pass on to future generations and the English we teach our children. A man who is cocooned from the real world, who has butlers and valets, helicopters and fast cars, yet who has seen more deprivation and who understands despair better than most politicians. A man whose life has been given over to duty to the institution he was born into, and who longs to modernise it, but who is thwarted by the very people his wife called ‘the enemy’ – the courtiers who rule royal life – and who must wait for the death of the mother he loves before he can begin his task. He is a man who cares above all else – even above his own happiness – for the future wellbeing of his sons. While they are children he can protect them, but he knows that as they come of age he will be powerless to stop the intrusion, the criticism and pressure that very nearly destroyed him.

ONE

Death of a Princess

‘They tell me there’s been an accident. What’s going on?’ Charles in the early hours of 31 August 1997

The first call alerting the Royal Family to Diana’s accident came through to Sir Robin Janvrin, the Queen’s deputy private secretary, at one o’clock on the morning of Sunday 31 August. He was asleep in his house on the Balmoral estate in Aberdeenshire. It was from the British ambassador in Paris, who had only sketchy news. There had been a car crash. Dodi Fayed, it seemed, had been killed, although there was no confirmation yet. The Princess of Wales, who had been travelling with him, was injured but no one knew how badly. Their car had smashed into the support pillars of a tunnel under the Seine. It had been travelling at high speed while trying to escape a group of paparazzi in hot pursuit on motorbikes.

Janvrin immediately telephoned the Queen and the Prince of Wales in their rooms at the castle. He then telephoned the Prince’s assistant private secretary, Nick Archer, who was staying in another house on the estate; also the Queen’s equerry and protection officers. They all agreed to meet in the offices at the castle, where they set up an operations room and manned the phones throughout the night.

Meanwhile, in London, the Prince’s team were being woken and told the news, ironically, by the tabloid press. The first call to Mark Bolland, the Prince’s deputy private secretary, came at 1 a.m. from the News of the World. Having gone to bed at his flat in the City after a very good dinner party, he let the answering machine take the call, and when he heard something about an accident in Paris dismissed it as the usual Saturday night fantasy. It was not until he heard the voice of Stuart Higgins, then editor of the Sun, a paper not published on a Sunday, speaking into the machine ten minutes later, that he realised something very odd was going on and picked up the phone. Higgins had much the same news as the Embassy. The reports were conflicting but it sounded as though Dodi had been killed and Diana injured.

The Prince’s press secretary, Sandy Henney, had also just gone to bed at her home in Surrey, having seen the last guest out after a fortieth birthday party for her sister-in-law. She too was woken by a journalist with a very similar story. The media, getting news directly from the emergency services, were in many ways better informed than the Embassy that night and provided a real service to the Prince’s staff.

Mark Bolland immediately rang Stephen Lamport, the Prince’s private secretary, at his home in west London, then Sandy Henney, and within minutes the phone lines across the capital and between London and Scotland were buzzing.

The Prince telephoned Bolland in London. ‘Robin tells me there’s been an accident. What’s going on?’

He wanted details. Shocked and unable to believe what he was hearing, he asked the same questions over and over again: What had caused the accident? What had Diana been doing in that situation? Who was driving? Where had it happened? Why had it happened? Questions to which, for the time being, there were no answers. They spoke for almost an hour.

There was no more concrete news. Reports one minute said Diana was seriously hurt, and the next suggested she had walked away with superficial injuries.

The Queen was also awake in her suite of rooms next door to her son’s on the first floor of the castle. Her private secretary, Sir Robert Fellowes, was on holiday in Norfolk, but like the Prince’s staff her own people were in constant touch with one another. The Prince’s private secretary on duty in Scotland was Nick Archer, but it was Stephen Lamport and Mark Bolland in London who were calling the shots.

Bolland telephoned Robin Janvrin to tell him that the Prince would be flying to Paris later that day to visit Diana in hospital, and needed a plane. ‘He’s going,’ he said. ‘This is not a matter for discussion. He is going to see his ex-wife.’

His request did not go down well initially. Was it the right thing to do? wondered Janvrin. An aeroplane of the Queen’s Flight couldn’t be ordered without the Queen’s specific agreement, and that was unlikely to be forthcoming.

‘Okay, fine,’ said Bolland. ‘We’ll take a scheduled flight from Aberdeen.’ The Queen would be irritated, no doubt, that yet again Diana was disrupting everyone’s lives. She had lost patience with Diana long ago, and as the week wore on she was confirmed in her belief that everything to do with her former daughter-in-law was always extraordinarily complicated.

Unbelievably, although the Queen and Prince Charles were just feet away from one another in their separate rooms, divided by paper-thin walls, it was their staff who were discussing the rights and wrongs of asking the Queen’s permission for Charles to use her aeroplane. Never was the true nature of this mother–son relationship more starkly demonstrated. Closely knit though the family appears, there is very little real communication between them. The Prince loves his parents dearly but they don’t talk. The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh had not known quite how serious the problems with their son’s marriage had been until 1987, when two friends wrote to the Queen, having decided independently and simultaneously that she ought to know what was going on. Their letters landed on her desk on the same day. They had witnessed some odd incidents, like Diana falling down the stairs at Sandringham, and Diana had told them on one occasion that her life with the Prince was impossible because of Mrs Parker Bowles, but they had not discussed the problems with their son.

That Sunday, Charles, William and Harry had all been planning to fly to London. The boys’ summer holiday was almost over and they were due to meet up with their mother, who was flying back from Paris. Diana always had the children for the last few days before they went back to school at the start of a new term, so that she could get everything ready and make sure they had the right kit. The Prince would spend a few days at Highgrove, his home in Gloucestershire, before heading for Provence, in the South of France, his habitual haunt in early September.

The Prince was in no doubt that he wanted to go and see Diana in Paris that morning, but uncertain whether he should take the children. He was worried that her injuries would be too upsetting for them. Clearly no decision could be made until they knew how bad her injuries were. And as the hours crept painfully past, he talked about the Princess, whom he still loved and prayed for every night, despite the failure of their marriage, despite the hurt that had existed between them.

‘I always thought it would end like this,’ he said, ‘with me having to nurse Diana through some terrible injury or illness. I always thought she’d come back to me and I would spend the rest of my time looking after her.’

The walls in Balmoral are so thin that there is no keeping of secrets. One regular visitor says that if you want to have a private conversation you have to put the plug in the wash basin and talk quietly, or it will be all round the castle. Inevitably, with this kind of drama going on, most of the family were by now awake and watching the television or listening to the radio, which was already given over to news of the accident. The Duke of York was staying in the castle at the time, also Princess Anne’s son Peter Phillips, then aged nineteen, two friends of the Queen and Princess Margaret, the Queen’s sister. William and Harry were asleep and it became a priority to get their radios out of their bedrooms and the television out of the nursery, to prevent them waking up and switching one of them on.

At about 3.30 a.m., Mark Bolland rang Robin Janvrin again to find out how he was doing with the plane, and whether he had woken up the people at RAF Northolt, in Greater London, where it was based. In the middle of the conversation, at 3.45, they were interrupted by a telephone call that came through from the Embassy in Paris for Janvrin, and he put Bolland on to Nick Archer while he took the call.

‘We can’t muck about with his plane,’ Bolland was saying. ‘Make sure Robin is quite clear what is going to happen …’

‘Oh, Mark, I think we’re going to have a change of plan.’

In the background Archer could hear Robin Janvrin breaking the news to the Prince of Wales on the telephone. ‘Sir, I’m very sorry to have to tell you, I’ve just had the Ambassador on the phone. The Princess died a short time ago.’

The announcement that went out at 4.30 a.m. said she had died at four o’clock. It had actually been earlier.

The Prince immediately rang Mark. ‘Robin has just told me she’s dead, Mark, is this true? What happened? What on earth was she doing there? How could this have happened? They’re all going to blame me, aren’t they? What do I do? What does this mean?’

Mark’s first reaction was to ring Camilla Parker Bowles to tell her that Diana had died, and warn her that she could expect a call at any moment from the Prince, in a state of serious distress. He had rung a number of close friends that night, and Camilla and the Prince had already spoken several times. She was shocked to the core by the news that Diana was dead, and utterly devastated for the boys; also terrified for the Prince, of what would happen to him, what people’s reaction would be.

Diana’s death came as a terrible shock to everyone. All the news had indicated that she had survived the crash, and with some reports having suggested she had walked away from the car, people were totally unprepared. The truth was that she had sustained terrible chest and head injuries. She had lost consciousness very soon after the impact, and never regained it. She had been treated in the wreckage of the Mercedes at the scene for about an hour and was then taken to the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital four miles away, where surgeons had fought for a further two hours to save her life, but in vain. The reaction was total horror and disbelief.

The Prince’s first thought was for the children. Should he wake them and tell them or let them sleep and tell them in the morning? He was absolutely dreading it, and didn’t know what to do for the best. The Queen felt strongly that they should be left to sleep and he took her advice and didn’t wake them up until 7.15. William had had a difficult night’s sleep and had woken many times. He had known, he said, that something awful was going to happen.

The Prince, like Camilla, realised only too well what the public reaction might be, and what the media would say. ‘They’re all going to blame me,’ he said. ‘The world’s going to go completely mad, isn’t it? We’re going to see a reaction that we’ve never seen before. And it could destroy everything. It could destroy the monarchy.’

‘Yes, sir, I think it could,’ said Lamport with brutal honesty. ‘It’s going to be very difficult for your mother, sir. She’s going to have to do things she may not want to do, or feel comfortable doing, but if she doesn’t do them, then that’s the end of it.’

The Queen’s first difficulty was upon her before dawn had broken. The Prince decided he should be the one to go to Paris to collect Diana’s body, but the Queen was against the idea and was strongly supported by her private secretary. The Princess was no longer a member of the Royal Family, argued Sir Robert Fellowes; it would be wrong to make too much fuss.

Robin Janvrin came up with the remark that clinched it. ‘What would you rather, Ma’am,’ he said; ‘that she came back in a Harrods’ van?’ There was no further argument.

Diana’s love affair with Dodi Fayed had been a source of deep concern to everyone at court, not least the Prince of Wales. Not because he resented her happiness – it was his deepest wish that Diana would find happiness – but because he feared it would end in disaster. He feared that Diana was in danger of being used by the al Fayed publicity machine. Dodi’s father, Mohamed al Fayed, the high-profile Egyptian owner of Harrods, was a controversial figure. Long denied British citizenship, he had tried relentlessly to ingratiate himself with the establishment. He had done some inspired matchmaking that summer between his playboy son and the Princess of Wales in the South of France, and had milked it for all it was worth. He had scarcely been out of the news for a month: he had been photographed with William and Harry, the Queen’s grandsons, who had been his guests on board his yacht, and was hoping for the greatest coup of all, to secure the mother of a future king of England as a daughter-in-law.

Dodi was a serious member of the international jet set, a kind and gentle man, but with more money than intellect, and a string of conquests to his name amongst the world’s most beautiful women. While he was busy wooing Diana, another woman thought she was engaged to marry him. He dabbled in the film business, but was essentially financed by his rich father, who denied him nothing. Dodi and Diana did appear to be in love, and may well have gone on to marry had things turned out differently. She would have been the biggest catch in the world for him. He would have provided the wealth she needed, even after her divorce settlement, to finance her enormously expensive lifestyle, and it would have been the ultimate two-fingered gesture to the Royal Family she so despised.

The boys had not enjoyed their holiday on board al Fayed’s yacht. They had not taken to Dodi or his father and had hated the publicity – as a result William had had a terrible row with his mother – and the whole trip had been extremely uncomfortable. And to add insult to injury, at the end of their stay, their two royal protection officers were taken aside by a Fayed aide, and handed a brown envelope each, stuffed with notes. ‘Mr al Fayed would like to thank you for all you have done,’ he said. In a panic, they immediately telephoned Colin Trimming, the Prince’s detective and head of the royal protection squad, and told him what had happened. ‘You’ve got to give it back,’ he said.

‘We’ve tried,’ they said, ‘but we were told that Mr al Fayed would be very upset if we didn’t accept it.’ The money went back.

The mention of Harrods to the Queen was enough to trigger Operation Overlord – the plan, which had been in existence for many years but never previously needed, to return the body of a member of the Royal Family to London. There is a BAe146 plane ear-marked for the purpose, which can be airborne at short notice from RAF Northolt. It had always been thought the Queen Mother might be its first passenger, which given she was then ninety-seven years old was not unreasonable. No one in their wildest dreams could have guessed it would be used for Diana, still so young and beautiful, super-fit and brimming with health and vitality.

The plane left Northolt at 10 a.m. that Sunday morning, bound for Aberdeen, with Stephen Lamport, Mark Bolland and Sandy Henney on board. First stop was RAF Wittering in Rutland, where it collected Diana’s sisters, Lady Sarah McCorquodale, who lived nearby, and Lady Jane Fellowes. It was Robert Fellowes who had broken the news to Diana’s family, and the Prince had telephoned Sarah to suggest they might like to go with him to collect the body, whereupon Jane had driven up from Norfolk to join her sister. From Wittering they flew to Aberdeen, where they collected the Prince of Wales, and then on to Paris. The Prince had decided this was not a trip for the children and so they stayed at Balmoral with Tiggy Legge-Bourke, who, as the Queen said, ‘by the grace of God’ had just arrived in Scotland ready to take the Princes down to London to meet their mother. She and their cousin Peter Phillips were utterly brilliant with William and Harry that day and for the remainder of the week.