Полная версия

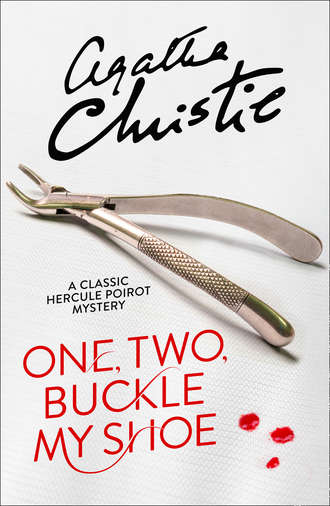

One, Two, Buckle My Shoe

‘You mean that there are people who would like him—out of the way?’

‘You bet there are. The Reds, to begin with—and our Blackshirted friends, too. It’s Blunt and his group who are standing solid behind the present Government. Good sound Conservative finance. That’s why, if there were the least chance that there was any funny stuff intended against him this morning, they wanted a thorough investigation.’

Poirot nodded.

‘That is what I more or less guessed. And that is the feeling I have’—he waved his hands expressively—‘that there was, perhaps—a hitch of some kind. The proper victim was—should have been—Alistair Blunt. Or is this only a beginning—the beginning of a campaign of some kind? I smell—I smell—’ he sniffed the air, ‘—big money in this business!’

Japp said:

‘You’re assuming a lot, you know.’

‘I am suggesting that ce pauvre Morley was only a pawn in the game. Perhaps he knew something—perhaps he told Blunt something—or they feared he would tell Blunt something—’

He stopped as Gladys Nevill entered the room.

‘Mr Reilly is busy on an extraction case,’ she said. ‘He will be free in about ten minutes if that will be all right?’

Japp said that it would. In the meantime, he said, he would have another talk to the boy Alfred.

Alfred was divided between nervousness, enjoyment, and a morbid fear of being blamed for everything that had occurred! He had only been a fortnight in Mr Morley’s employment, and during that fortnight he had consistently and unvaryingly done everything wrong. Persistent blame had sapped his self-confidence.

‘He was a bit rattier than usual, perhaps,’ said Alfred in answer to a question, ‘nothing else as I can remember. I’d never have thought he was going to do himself in.’

Poirot interposed.

‘You must tell us,’ he said, ‘everything that you can remember about this morning. You are a very important witness, and your recollections may be of immense service to us.’

Alfred’s face was suffused by vivid crimson and his chest swelled. He had already given Japp a brief account of the morning’s happenings. He proposed now to spread himself. A comforting sense of importance oozed into him.

‘I can tell you orl right,’ he said. ‘Just you ask me.’

‘To begin with, did anything out of the way happen this morning?’

Alfred reflected a minute and then said rather sadly: ‘Can’t say as it did. It was orl just as usual.’

‘Did any strangers come to the house?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Not even among the patients?’

‘I didn’t know as you meant the patients. Nobody come what hadn’t got an appointment, if that’s what you mean. They were all down in the book.’

Japp nodded. Poirot asked:

‘Could anybody have walked in from outside?’

‘No, they couldn’t. They’d have to have a key, see?’

‘But it was quite easy to leave the house?’

‘Oh, yes, just turn the handle and go out and pull the door to after you. As I was saying most of ’em do. They often come down the stairs while I’m taking up the next party in the lift, see?’

‘I see. Now just tell us who came first this morning and so on. Describe them if you can’t remember their names.’

Alfred reflected a minute. Then he said: ‘Lady with a little girl, that was for Mr Reilly and a Mrs Soap or some such name for Mr Morley.’

Poirot said:

‘Quite right. Go on.’

‘Then another elderly lady—bit of a toff she was—come in a Daimler. As she went out a tall military gent come in, and just after him, you came,’ he nodded to Poirot.

‘Right.’

‘Then the American gent came—’

Japp said sharply:

‘American?’

‘Yes, sir. Young fellow. He was American all right—you could tell by his voice. Come early, he did. His appointment wasn’t till eleven-thirty—and what’s more he didn’t keep it—neither.’

Japp said sharply:

‘What’s that?’

‘Not him. Come in for him when Mr Reilly’s buzzer went at eleven-thirty—a bit later it was, as a matter of fact, might have been twenty to twelve—and he wasn’t there. Must have funked it and gone away.’ He added with a knowledgeable air, ‘They do sometimes.’

Poirot said:

‘Then he must have gone out soon after me?’

‘That’s right, sir. You went out after I’d taken up a toff what come in a Rolls. Coo—it was a loverly car, Mr Blunt—eleven-thirty. Then I come down and let you out, and a lady in. Miss Some Berry Seal, or something like that—and then I—well, as a matter of fact I just nipped down to the kitchen to get my elevenses, and when I was down there the buzzer went—Mr Reilly’s buzzer—so I come up and, as I say, the American gentleman had hooked it. I went and told Mr Reilly and he swore a bit, as is his way.’

Poirot said:

‘Continue.’

‘Lemme see, what happened next? Oh, yes, Mr Morley’s buzzer went for that Miss Seal, and the toff came down and went out as I took Miss Whatsername up in the lift. Then I come down again and two gentlemen came—one a little man with a funny squeaky voice—I can’t remember his name. For Mr Reilly, he was. And a fat foreign gentleman for Mr Morley.

‘Miss Seal wasn’t very long—not above a quarter of an hour. I let her out and then I took up the foreign gentleman. I’d already taken the other gent into Mr Reilly right away as soon as he came.’

Japp said:

‘And you didn’t see Mr Amberiotis, the foreign gentleman, leave?’

‘No, sir, I can’t say as I did. He must have let himself out. I didn’t see either of those two gentlemen go.’

‘Where were you from twelve o’clock onwards?’

‘I always sit in the lift, sir, waiting until the front-door bell or one of the buzzers goes.’

Poirot said:

‘And you were perhaps reading?’

Alfred blushed again.

‘There ain’t no harm in that, sir. It’s not as though I could be doing anything else.’

‘Quite so. What were you reading?’

‘Death at Eleven-Forty-Five, sir. It’s an American detective story. It’s a corker, sir, it really is! All about gunmen.’

Poirot smiled faintly. He said:

‘Would you hear the front door close from where you were?’

‘You mean anyone going out? I don’t think I should, sir. What I mean is, I shouldn’t notice it! You see, the lift is right at the back of the hall and a little round the corner. The bell rings just behind it, and the buzzers too. You can’t miss them.’

Poirot nodded and Japp asked:

‘What happened next?’

Alfred frowned in a supreme effort of memory.

‘Only the last lady, Miss Shirty. I waited for Mr Morley’s buzzer to go, but nothing happened and at one o’clock the lady who was waiting, she got rather ratty.’

‘It did not occur to you to go up before and see if Mr Morley was ready?’

Alfred shook his head very positively.

‘Not me, sir. I wouldn’t have dreamed of it. For all I knew the last gentleman was still up there. I’d got to wait for the buzzer. Of course if I’d knowed as Mr Morley had done himself in—’

Alfred shook his head with morbid relish.

Poirot asked:

‘Did the buzzer usually go before the patient came down, or the other way about?’

‘Depends. Usually the patient would come down the stairs and then the buzzer would go. If they rang for the lift, that buzzer would go perhaps as I was bringing them down. But it wasn’t fixed in any way. Sometimes Mr Morley would be a few minutes before he rang for the next patient. If he was in a hurry, he’d ring as soon as they were out of the room.’

‘I see—’ Poirot paused and then went on:

‘Were you surprised at Mr Morley’s suicide, Alfred?’

‘Knocked all of a heap, I was. He hadn’t no call to go doing himself in as far as I can see—oh!’ Alfred’s eyes grew large and round. ‘Oo—er—he wasn’t murdered, was he?’

Poirot cut in before Japp could speak.

‘Supposing he were, would it surprise you less?’

‘Well, I don’t know, sir, I’m sure. I can’t see who’d want to murder Mr Morley. He was—well, he was a very ordinary gentleman, sir. Was he really murdered, sir?’

Poirot said gravely:

‘We have to take every possibility into account. That is why I told you you would be a very important witness and that you must try and recollect everything that happened this morning.’

He stressed the words and Alfred frowned with a prodigious effort of memory.

‘I can’t think of anything else, sir. I can’t indeed.’

Alfred’s tone was rueful.

‘Very good, Alfred. And you are quite sure no one except patients came to the house this morning?’

‘No stranger did, sir. That Miss Nevill’s young man came round—and in a rare taking not to find her here.’

Japp said sharply:

‘When was that?’

‘Some time after twelve it was. When I told him Miss Nevill was away for the day, he seemed very put out and he said he’d wait and see Mr Morley. I told him Mr Morley was busy right up to lunch time, but he said: Never mind, he’d wait.’

Poirot asked:

‘And did he wait?’

A startled look came into Alfred’s eyes. He said:

‘Cor—I never thought of that! He went into the waiting-room, but he wasn’t there later. He must have got tired of waiting, and thought he’d come back another time.’

When Alfred had gone out of the room, Japp said sharply:

‘D’you think it wise to suggest murder to that lad?’

Poirot shrugged his shoulders.

‘I think so—yes. Anything suggestive that he may have seen or heard will come back to him under the stimulus, and he will be keenly alert to everything that goes on here.’

‘All the same, we don’t want it to get about too soon.’

‘Mon cher, it will not. Alfred reads detective stories—Alfred is enamoured of crime. Whatever Alfred lets slip will be put down to Alfred’s morbid criminal imagination.’

‘Well, perhaps you are right, Poirot. Now we’ve got to hear what Reilly has to say.’

Mr Reilly’s surgery and office were on the first floor. They were as spacious as the ones above but had less light in them, and were not quite so richly appointed.

Mr Morley’s partner was a tall, dark young man, with a plume of hair that fell untidily over his forehead. He had an attractive voice and a very shrewd eye.

‘We’re hoping, Mr Reilly,’ said Japp, after introducing himself, ‘that you can throw some light on this matter.’

‘You’re wrong then, because I can’t,’ replied the other. ‘I’d say this—that Henry Morley was the last person to go taking his own life. I might have done it—but he wouldn’t.’

‘Why might you have done it?’ asked Poirot.

‘Because I’ve oceans of worries,’ replied the other. ‘Money troubles, for one! I’ve never yet been able to suit my expenditure to my income. But Morley was a careful man. You’ll find no debts, nor money troubles, I’m sure of that.’

‘Love affairs?’ suggested Japp.

‘Is it Morley you mean? He had no joy of living at all! Right under his sister’s thumb he was, poor man.’

Japp went on to ask Reilly details about the patients he had seen that morning.

‘Oh, I fancy they’re all square and above-board. Little Betty Heath, she’s a nice child—I’ve had the whole family one after another. Colonel Abercrombie’s an old patient, too.’

‘What about Mr Howard Raikes?’ asked Japp.

Reilly grinned broadly.

‘The one who walked out on me? He’s never been to me before. I know nothing about him. He rang up and particularly asked for an appointment this morning.’

‘Where did he ring up from?’

‘Holborn Palace Hotel. He’s an American, I fancy.’

‘So Alfred said.’

‘Alfred should know,’ said Mr Reilly. ‘He’s a film fan, our Alfred.’

‘And your other patient?’

‘Barnes? A funny precise little man. Retired Civil Servant. Lives out Ealing way.’

Japp paused a minute and then said:

‘What can you tell us about Miss Nevill?’

Mr Reilly raised his eyebrows.

‘The bee-yewtiful blonde secretary? Nothing doing, old boy! Her relations with old Morley were perfectly pewer—I’m sure of it.’

‘I never suggested they weren’t,’ said Japp, reddening slightly.

‘My fault,’ said Reilly. ‘Excuse my filthy mind, won’t you? I thought it might be an attempt on your part to cherchez la femme.

‘Excuse me for speaking your language,’ he added parenthetically to Poirot. ‘Beautiful accent, haven’t I? It comes of being educated by nuns.’

Japp disapproved of this flippancy. He asked:

‘Do you know anything about the young man she is engaged to? His name is Carter, I understand. Frank Carter.’

‘Morley didn’t think much of him,’ said Reilly. ‘He tried to get la Nevill to turn him down.’

‘That might have annoyed Carter?’

‘Probably annoyed him frightfully,’ agreed Mr Reilly cheerfully.

He paused and then added:

‘Excuse me, this is a suicide you are investigating, not a murder?’

Japp said sharply:

‘If it were a murder, would you have anything to suggest?’

‘Not I! I’d like it to be Georgina! One of those grim females with temperance on the brain. But I’m afraid Georgina is full of moral rectitude. Of course I could easily have nipped upstairs and shot the old boy myself, but I didn’t. In fact, I can’t imagine anyone wanting to kill Morley. But then I can’t conceive of his killing himself.’

He added—in a different voice:

‘As a matter of fact, I’m very sorry about it … You mustn’t judge by my manner. That’s just nervousness, you know. I was fond of old Morley and I shall miss him.’

Japp put down the telephone receiver. His face, as he turned to Poirot, was rather grim.

He said:

‘Mr Amberiotis isn’t feeling very well—would rather not see any one this afternoon.

‘He’s going to see me—and he’s not going to give me the slip either! I’ve got a man at the Savoy ready to trail him if he tries to make a get-away.’

Poirot said thoughtfully:

‘You think Amberiotis shot Morley?’

‘I don’t know. But he was the last person to see Morley alive. And he was a new patient. According to his story, he left Morley alive and well at twenty-five minutes past twelve. That may be true or it may not. If Morley was all right then we’ve got to reconstruct what happened next. There was still five minutes to go before his next appointment. Did someone come in and see him during that five minutes? Carter, say? Or Reilly? What happened? Depend upon it, by half-past twelve, or five-and-twenty to one at the latest, Morley was dead—otherwise he’d either have sounded his buzzer or else sent down word to Miss Kirby that he couldn’t see her. No, either he was killed, or else somebody told him something which upset the whole tenor of his mind, and he took his own life.’

He paused.

‘I’m going to have a word with every patient he saw this morning. There’s just the possibility that he may have said something to one of them that will put us on the right track.’

He glanced at his watch.

‘Mr Alistair Blunt said he could give me a few minutes at four-fifteen. We’ll go to him first. His house is on Chelsea Embankment. Then we might take the Sainsbury Seale woman on our way to Amberiotis. I’d prefer to know all we can before tackling our Greek friend. After that, I’d like a word or two with the American who, according to you “looked like murder”.’

Hercule Poirot shook his head.

‘Not murder—toothache.’

‘All the same, we’ll see this Mr Raikes. His conduct was queer to say the least of it. And we’ll check up on Miss Nevill’s telegram and on her aunt and on her young man. In fact, we’ll check up on everything and everybody!’

Alistair Blunt had never loomed large in the public eye. Possibly because he was himself a very quiet and retiring man. Possibly because for many years he had functioned as a Prince Consort rather than as a King.

Rebecca Sanseverato, née Arnholt, came to London a disillusioned woman of forty-five. On either side she came of the Royalty of wealth. Her mother was an heiress of the European family of Rothersteins. Her father was the head of the great American banking house of Arnholt. Rebecca Arnholt, owing to the calamitous deaths of two brothers and a cousin in an air accident, was sole heiress to immense wealth. She married a European aristocrat with a famous name, Prince Felipe di Sanseverato. Three years later she obtained a divorce and custody of the child of the marriage, having spent two years of wretchedness with a well-bred scoundrel whose conduct was notorious. A few years later her child died.

Embittered by her sufferings, Rebecca Arnholt turned her undoubted brains to the business of finance—the aptitude for it ran in her blood. She associated herself with her father in banking.

After his death she continued to be a powerful figure in the financial world with her immense holdings. She came to London—and a junior partner of the London house was sent to Claridge’s to see her with various documents. Six months later the world was electrified to hear that Rebecca Sanseverato was marrying Alistair Blunt, a man nearly twenty years younger than herself.

There were the usual jeers—and smiles. Rebecca, her friends said, was really an incurable fool where men were concerned! First Sanseverato—now this young man. Of course he was only marrying her for her money. She was in for a second disaster! But to everyone’s surprise the marriage was a success. The people who prophesied that Alistair Blunt would spend her money on other women were wrong. He remained quietly devoted to his wife. Even after her death, ten years later, when as inheritor of her vast wealth he might have been supposed to cut loose, he did not marry again. He lived the same quiet and simple life. His genius for finance had been no less than his wife’s. His judgements and dealings were sound—his integrity above question. He dominated the vast Arnholt and Rotherstein interests by his sheer ability.

He went very little into society, had a house in Kent and one in Norfolk where he spent weekends—not with gay parties, but with a few quiet stodgy friends. He was fond of golf and played moderately well. He was interested in his garden.

This was the man towards whom Chief Inspector Japp and Hercule Poirot were bouncing along in a somewhat elderly taxi.

The Gothic House was a well-known feature on Chelsea Embankment. Inside it was luxurious with an expensive simplicity. It was not very modern but it was eminently comfortable.

Alistair Blunt did not keep them waiting. He came to them almost at once.

‘Chief Inspector Japp?’

Japp came forward and introduced Hercule Poirot. Blunt looked at him with interest.

‘I know your name, of course, M. Poirot. And surely—somewhere—quite recently—’ he paused, frowning.

Poirot said:

‘This morning, Monsieur, in the waiting-room of ce pauvre M. Morley.’

Alistair Blunt’s brow cleared. He said:

‘Of course. I knew I had seen you somewhere.’ He turned to Japp. ‘What can I do for you? I am extremely sorry to hear about poor Morley.’

‘You were surprised, Mr Blunt?’

‘Very surprised. Of course I knew very little about him, but I should have thought him a most unlikely person to commit suicide.’

‘He seemed in good health and spirits then, this morning?’

‘I think so—yes.’ Alistair Blunt paused, then said with an almost boyish smile: ‘To tell you the truth, I’m a most awful coward about going to the dentist. And I simply hate that beastly drill thing they run into you. That’s why I really didn’t notice anything much. Not till it was over, you know, and I got up to go. But I must say Morley seemed perfectly natural then. Cheerful and busy.’

‘You have been to him often?’

‘I think this was my third or fourth visit. I’ve never had much trouble with my teeth until the last year. Breaking up, I suppose.’

Hercule Poirot asked:

‘Who recommended Mr Morley to you originally?’

Blunt drew his brows together in an effort of concentration.

‘Let me see now—I had a twinge—somebody told me Morley of Queen Charlotte Street was the man to go to—no, I can’t for the life of me remember who it was. Sorry.’

Poirot said:

‘If it should come back to you, perhaps you will let one of us know?’

Alistair Blunt looked at him curiously.

He said:

‘I will—certainly. Why? Does it matter?’

‘I have an idea,’ said Poirot, ‘that it might matter very much.’

They were going down the steps of the house when a car drew up in front of it. It was a car of sporting build—one of those cars from which it is necessary to wriggle from under the wheel in sections.

The young woman who did so appeared to consist chiefly of arms and legs. She had finally dislodged herself as the men turned to walk down the street.

The girl stood on the pavement looking after them. Then, suddenly and vigorously, she ejaculated, ‘Hi!’

Not realizing that the call was addressed to them, neither man turned, and the girl repeated: ‘Hi! Hi! You there!’

They stopped and looked round inquiringly. The girl walked towards them. The impression of arms and legs remained. She was tall, thin, and her face had an intelligence and aliveness that redeemed its lack of actual beauty. She was dark with a deeply tanned skin.

She was addressing Poirot:

‘I know who you are—you’re the detective man, Hercule Poirot!’ Her voice was warm and deep, with a trace of American accent.

Poirot said:

‘At your service, Mademoiselle.’

Her eyes went on to his companion.

Poirot said:

‘Chief Inspector Japp.’

Her eyes widened—almost it seemed with alarm. She said, and there was a slight breathlessness in her voice:

‘What have you been doing here? Nothing—nothing has happened to Uncle Alistair, has it?’

Poirot said quickly:

‘Why should you think so, Mademoiselle?’

‘It hasn’t? Good.’

Japp took up Poirot’s question. ‘Why should you think anything had happened to Mr Blunt, Miss—’

He paused inquiringly.

The girl said mechanically:

‘Olivera. Jane Olivera.’ Then she gave a slight and rather unconvincing laugh. ‘Sleuths on the doorstep rather suggest bombs in the attic, don’t they?’

‘There’s nothing wrong with Mr Blunt, I’m thankful to say, Miss Olivera.’

She looked directly at Poirot.

‘Did he call you in about something?’

Japp said:

‘We called on him, Miss Olivera, to see if he could throw any light on a case of suicide that occurred this morning.’

She said sharply:

‘Suicide? Whose? Where?’

‘A Mr Morley, a dentist, of 58, Queen Charlotte Street.’

‘Oh!’ said Jane Olivera blankly. ‘Oh!—’ She stared ahead of her, frowning. Then she said unexpectedly:

‘Oh, but that’s absurd!’ And turning on her heel she left them abruptly and without ceremony, running up the steps of the Gothic House and letting herself in with a key.

‘Well!’ said Japp, staring after her, ‘that’s an extraordinary thing to say.’

‘Interesting,’ observed Poirot mildly.

Japp pulled himself together, glanced at his watch and hailed an approaching taxi.

‘We’ll have time to take the Sainsbury Seale on our way to the Savoy.’

Miss Sainsbury Seale was in the dimly lit lounge of the Glengowrie Court Hotel having tea.

She was flustered by the appearance of a police officer in plain clothes—but her excitement was of a pleasurable nature, he observed. Poirot noticed, with sorrow, that she had not yet sewn the buckle on her shoe.

‘Really, officer,’ fluted Miss Sainsbury Seale, glancing round, ‘I really don’t know where we could go to be private. So difficult—just tea-time—but perhaps you would care for some tea—and—and your friend?’