Полная версия

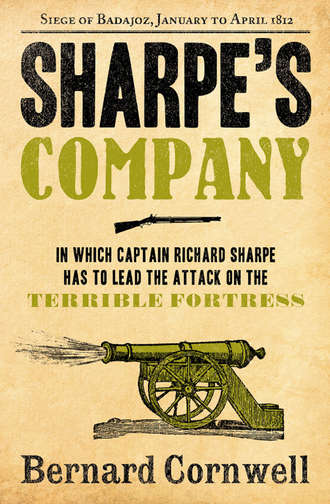

Sharpe’s Company: The Siege of Badajoz, January to April 1812

‘I know!’ They fired again, a fraction early, and it was plain that no man could climb past their fire. They were dug into the very heart of the town’s thick, low wall and no British siege gun could have hoped to reach them; not unless Wellington had fired at each hidden casement for a week until the whole wall collapsed like the breach itself. In front of each gun, revealed by the burning carcasses, was a trench that defended the gunners from their enemy on the breach, and as long as the two guns were firing, across and slightly ahead of each other, there could be no victory.

The troops were climbing again, slower now, wary of the guns and trying to avoid the burning grenades that the French were tossing on to the slope. The red explosions punctured the scattered attackers. Sharpe turned to Harper. ‘Are you loaded?’

The huge Sergeant nodded, grinned, and held up the seven-barrelled gun. Sharpe grinned back. ‘Shall we join in?’

Lawford shouted at them. ‘What are you doing?’

Sharpe pointed at the nearest side of the breach. ‘Going after the gun. Do you mind?’

Lawford shrugged. ‘Be careful!’

There was no time to think, just to jump into the ditch and pray that their ankles would not twist or break. Sharpe fell awkwardly, slipping on the snow, but a huge hand grabbed his greatcoat, hauled him upright, and the two men ran across the floor of the ditch. The jump had been twenty feet and it seemed as if they had fallen into the bottom of a giant cauldron, an alchemist’s vessel of fire, and the flames poured in from above. Carcasses rolled down, musket and cannon flame spat from above, and the fire spilt on to the living and dead flesh in the ditch and was reflected red on the underside of the low clouds that rolled southwards to Badajoz. There was only one way to live in the cauldron, and that was to go upwards, and the column was climbing again as Sharpe and Harper skirted the mass of men, and then the guns spoke, and the attack was flung back by the flame-borne grape-shot.

Sharpe had been counting the gaps between the shots and knew that the French gunners were taking about a minute to reload each giant gun. He counted the seconds in his head as the two men struggled past the mass of Irishmen to the left of the breach. They fought their way through the crush, going for the very edge of the slope, and the surge of men carried them forward so that, for an instant, Sharpe thought they would be carried on to the rubble slope itself. Then the guns fired again and the men ahead recoiled, something wet slapped Sharpe’s face, and the attack was broken into small groups. He had a minute. ‘Patrick!’

They threw themselves into the trench beside the breach, the trench that protected the gun. It was already filled with men sheltering from the grapeshot. The French gunners, over their heads, would be sponging out and desperately ramming the huge, serge bags of powder into the vast muzzles while other men waited with the lumpy, black bags of grapeshot. Sharpe tried to forget them. He looked up the wall to the casement’s lip. It was high up, far higher than a man’s height, so he braced his back on the wall, cupped his hands and nodded to the Sergeant. Harper put a massive boot into Sharpe’s hands, cocked the seven-barrelled gun, and nodded back. Sharpe heaved and Harper pushed up, the Irishman weighed as much as a small bullock. Sharpe grimaced with the effort and then two of the Connaught Rangers, seeing their intention, joined in and pushed up on Harper’s legs. The weight suddenly disappeared. Harper had grasped the casement’s edge with one hand, ignoring the musket bullets that flattened themselves on the wall beside him, threw the huge gun over the edge, aimed blindly, and pulled the trigger.

The recoil slammed him back, cruelly throwing him on the opposite lip of the trench, but he scrambled to his feet, screaming in Gaelic. Sharpe knew he was telling his countrymen to climb the wall and attack the gun crew while they were still dazed by the shattering blast. But it was hopeless trying to climb the steep wall, and Sharpe thought of the surviving gunners loading the huge cannon. ‘Patrick! Throw me!’

Harper seized Sharpe like a bag of oats, took one breath, and threw him bodily upwards. It was like being lifted by a mine explosion. Sharpe flailed, his rifle slipping from his shoulder, but he caught it by the barrel, saw the casement’s edge and desperately threw out his left hand. It held, he had a leg on the stonework; he knew the French muskets were firing at him, but he had no time to think of that for a man was running at him, a rammer raised to strike down, and Sharpe struck out with his rifle. It was a lucky effort. The brass-hilted butt caught the Frenchman on the temple, he staggered back, and Sharpe had dropped over the casement, found his feet, and the huge sword rasped out of the scabbard and the joy was there.

The gunners had been hit hard by the seven bullets that had ricocheted round the stone emplacement. Sharpe could see bodies lying beneath the huge, iron barrel of what he recognized as a siege gun, but there were still men alive and they were coming at him. He swung the long blade at them, drove them back, hacked down with the sword and felt it shudder as it cleaved a skull. He screamed at them, scaring them, slipped on new blood, tugged the blade free and swung again. The French went back. They outnumbered him six to one, but they were gunners more used to killing at a distance than seeing the face of their enemy wild over a naked sword. They cowered back and Sharpe turned, back to the casement’s edge, and found an arm clinging desperately to the stonework. He grabbed the wrist and heaved a Connaught Ranger into the sunken gun-pit. The man’s eyes were bright with excitement. Sharpe yelled at him. ‘Help the others up! Use your sling!’

A musket ball went past his head, clanging off the barrel of the gun, and Sharpe whirled to see the familiar uniforms of French infantry running down the stone stairs to rescue the gun. He went for them, wild with the madness of battle, and the crazy thought whirled in his head that he wished the mean-faced bastard clerk in Whitehall could see him now. Perhaps then Whitehall would know what its soldiers did, but there was no time for the thought because the infantry were coming down the narrow space beside the barrel. He leaped at them, shouting and lunging with the point to drive them back and he knew he was outnumbered.

They checked, let him come, and then countered with their long bayonets. The sword was not long enough! He swung at them, smashing bayonets to the side, but another came past his swing and he felt the blade catch in his greatcoat. He seized the barrel with his left hand, pulled the man off balance and brought the great brass hilt of the sword down on his head. He was forced back. Another bayonet flickered at him, making him dodge wildly so that he slipped against the siege gun, his sword was whirling uselessly, flailing for balance, and he saw the bayonets above him. His anger was useless because he could not parry.

The shout was in a language he did not speak, but the voice was Harper’s and the massive Irishman was crunching the enemy with the seven-barrelled gun held like a club. He ignored Sharpe, stepped over him, laughed at the French, swung at them and went forward as his ancestors had gone into fine, dawn-misted battles. He chanted the same words that his ancestors had, and the Connaught men were beside him and no troops in the world could have stood against their anger and their attack. Sharpe ducked under the barrel and there were more enemy, fearful now, and he hacked up with the blade, drove them back, stabbed with it, screaming the challenge. The French scrambled for the stone stairs in their rear, and the crazed men in red and green coats came on, stepping over the bodies, hacking and clawing at them. Sharpe felt the blade grate on a rib and he swung it clear, and suddenly the only enemy were the survivors who cowered at the foot of the stairs, shouting their surrender. They had no hope. The men of Connaught had lost friends on the breach, old friends, and the blades were used in short, efficient strokes. The bayonets ignored the French cries, worked swiftly, and the casement was thick with the smell of fresh blood.

‘Up!’ There were still enemies on the wall, enemies that could fire down into the gun-pit, and Sharpe climbed the stairs, the sword a streak of reflected firelight ahead of him, and suddenly the night air was cool and clear and he was on the wall. The infantry had fallen back down the ramparts, fearful of the carnage round the gun, and Sharpe stood at the stair’s head and watched them. Harper joined him, with a group of red-jacketed 88th, and they panted so that their breath fogged.

Harper laughed. ‘They’ve had enough!’

It was true. The French were pulling back, abandoning the breach, and only one man, an officer, tried to force them back. He shouted at them, beat at them with his sword, and then, seeing that they would not attack, came on himself. He was a slim man with a thin, fair moustache beneath a straight, hooked nose. Sharpe could see the man’s fear. The Frenchman did not want to make a solo attack, but he had his pride, and he hoped his men would follow. They did not. Instead they called to him, told him not to be a fool, but he walked on, looking at Sharpe, and his sword was ridiculously slim as he lowered it to the guard. He said something to Sharpe, who shook his head, but the Frenchman insisted and lunged at Sharpe, who was forced to leap back and bring up the huge sword in a clumsy parry. Sharpe’s anger had gone in the cool air, the fight was over, and he was irritated by the Frenchman’s insistence. ‘Go away! Vamos!’ He tried to remember the words in French, but he could not.

The Irish laughed. ‘Put him over your knee, Captain!’ The Frenchman was little more than a boy, ridiculously young, but brave. He came forward again, the sword level, and this time Sharpe jumped towards him, growled, and the Frenchman rocked back.

Sharpe dropped his own blade. ‘Give up!’

The answer was another lunge that came close to Sharpe’s chest. He leaned back and beat the sword aside. He could feel his anger returning. He swore at the man, jerked his head down the ramparts, but still the fool came forward, incensed by the Irish laughter, and again Sharpe had to parry and force him back.

Harper finished the farce. He had worked his way behind the officer and, as the Frenchman looked at Sharpe for another attack, the Sergeant coughed. ‘Sir? Monsewer?’ The officer looked round. The giant Irishman smiled at him, came forward unarmed and very slowly. ‘Monsewer?’

The officer nodded to Harper, frowned, and said something in French. The huge Sergeant nodded seriously. ‘Quite right, sir, quite right.’ Then a giant fist travelled from some place low down, up, and straight on to the Frenchman’s chin. He crumpled, the Connaught men gave an ironic cheer, and Harper laid the senseless body beside the rampart. ‘Poor wee fool.’ He grinned at Sharpe, immensely pleased with himself, and looked over towards the breach. The fight still went on, but Harper knew his part in the assault was done, and well done, and that nothing could touch him this night. He jerked his thumb at the Connaught Rangers and looked at Sharpe. ‘Connaught lads, sir. Good fighters.’

‘They are.’ Sharpe grinned. ‘Where’s Connaught? Wales?’

Harper made a joke at Sharpe’s expense, but in Gaelic, so that he was forced to listen to the Rangers’ good-humoured laughter. They were in good spirits, happy, like the Sergeant from Donegal, that they had played a good part in this night’s fight, a part that would make a fine story to weave through the long winter nights in some unimaginable future. Harper knelt to go through the unconscious Frenchman’s pockets and Sharpe turned to look at the breach.

The 45th, on the far side, were dealing with the second gun. They had found planks, abandoned in the trench, and thrown them over to the casement lip and Sharpe watched, admiringly, as the Nottinghamshire men charged across the perilous path and took their long bayonets to the gun crew. The growl had become a whoop of victory and the dark beast in the ditch uncoiled across the undefended breach and swarmed past the two silent guns towards the streets of the town. A few shots came from doors and windows, but only a few, and the British horde flooded down the rubble to where the breach had smothered the old mediaeval wall. It was over.

Or nearly. A second mine had been put in the ruins of the old wall. Black powder had been crammed into an old postern and now the French lit the fuse and ran back into the streets. The mine exploded. Flame streaked up from the darkness, old stones shattered outwards, boiling smoke and dust, and with it came the stench of roasted flesh and the head of the victorious column was uselessly decimated. For a second there was a stunned silence, time just to draw breath, and then the shout was not for victory, but for revenge, and the troops took their anger into the defenceless streets.

Harper watched the howling mob flow into the city. ‘You think we’re invited?’

‘Why not?’

The Sergeant grinned. ‘God knows, we’ve deserved it.’ He was dangling a gold watch and chain and he started forward towards the ramp that led down towards the houses. Sharpe followed and suddenly stopped. He froze.

Down where the second mine had exploded, lit by a flickering length of old timber, was a mangled body. One side seemed sleek with new blood, a sleekness speckled with the ivory of bone, but the other side was gorgeous in yellow facings and gold lace. A fur-trimmed cavalry cloak covered the legs. ‘Oh God!’

Harper heard him and saw where he was looking. Then both men were racing down the ramp, slipping on ice and slushy snow, and running towards Lawford’s body.

Ciudad Rodrigo was won; but not at this price, Sharpe thought, dear God, not at this price.

CHAPTER FOUR

There was a scream from inside the town, shots as men blew open the doors of houses, and over it all the sound of triumphant voices. After the fight, the reward.

Harper reached the body first, plucked the cloak to one side, and bent over the bloodied chest. ‘He’s alive, sir.’

It seemed to Sharpe like a parody of life. The explosion had sheared Lawford’s left arm almost clean from his body, crushed the ribs and flicked them open so they protruded through the remnants of skin and flesh. The blood was flowing beneath the once immaculate uniform. Harper began tearing the cloak into strips, his mouth a tight line of anger and sorrow. Sharpe looked towards the breach where men still clambered towards the houses. ‘Bandsmen!’

The bands had played during the assault. He remembered hearing the music and now, idiotically, he could suddenly identify the tune he had heard. ‘The Downfall of Paris’. By now the bandsmen should be doing their other job, of caring for the wounded, but he could see none. ‘Bandsmen!’

Miraculously Lieutenant Price appeared, pale and unsteady, and with him a small group of the Light Company. ‘Sir?’

‘A stretcher. Fast! And send someone back to battalion.’

Price saluted. He had forgotten the drawn sword in his hand so that the blade, a curved sabre, nearly sliced into Private Peters. ‘Sir.’ The small group ran back.

Lawford was unconscious. Harper was binding the chest, his huge fingers astonishingly gentle with the tattered flesh. He looked up at Sharpe. ‘Take the arm off, sir.’

‘What?’

‘Better now than later, sir.’ The Sergeant pointed at the Colonel’s left arm, held by a single, glistening shred of tissue. ‘He might live, sir, so he might, but the arm will have to go.’

A splintered piece of bone protruded from the stump. The arm was bent unnaturally upwards, pointing towards the city, and Harper was binding the brief stump to stop the weakly pulsing blood. Sharpe picked his way to Lawford’s head, treading carefully for the ground was slick, though whether with blood or ice it was impossible to see. The only light came from the burning timber. He put the point of his sword down into the bloodied mess and Harper moved the blade till it was in the right place. ‘Leave the skin, sir. It’ll flap over.’

It was no different from butchering a pig or a bullock, but it felt different. He could hear crashes from the city, punctuating the screams. ‘Is that right?’ He could feel Harper manipulating the blade.

‘Now, sir. Straight down.’

Sharpe pushed down, with both hands, almost as if he was driving a stake into mud. Human flesh is resilient, proof against all but the hottest stroke, and Sharpe felt the gorge rise in his throat as the sword met resistance and he heaved down so that Lawford tipped in the scarlet slush and the Colonel’s lips grimaced. Then it was done, the arm free, and Sharpe stooped to the dead fingers and pulled off a gold ring. He would give it to Forrest to be sent home with the Colonel or, God forbid, to be sent to his relatives.

Lieutenant Price was back. ‘They’re coming, sir.’

‘Who?’

‘The Major, sir.’

‘A stretcher?’

Price nodded, looking sick. ‘Will he live, sir?’

‘How the hell do I know?’ It was not fair to vent his anger on Price. ‘What was he doing here anyway?’

Price shrugged miserably. ‘He said he was going to find you, sir.’

Sharpe stared down at the handsome Colonel and swore. Lawford had no business in the breach. The same, perhaps, could have been said of Sharpe and Harper, but the tall Rifleman saw a difference. Lawford had a future, hopes, a family to protect, ambitions that were within his grasp, and soldiering was not where those ambitions finally lay. They might all be thrown away for one mad moment in a breach, a moment to prove something. Sharpe and Harper had no such future, no such hopes, only the knowledge that they were soldiers, as good as their last battle, useful as long as they could fight. They were both, Sharpe thought, adventurers, gambling with their lives. He looked at the Colonel. It was such a waste.

Sharpe listened to the great noise coming from the city, a noise of rampage and victory. Once, perhaps, he thought, an adventurer had a future, back when the world was free and a sword was the passport to any hope. Not now. Everything was changing with a suddenness and pace that was bewildering. Three years before, when the army had defeated the French at Vimiero, it had been a small army, almost an intimate army, and the General could inspect all his troops in a single morning and have time to recognize them, remember them. Sharpe had known most officers in the line by face, if not by name, and was welcome at their evening fires. Not now. Now there were generals of this and generals of that, of division and brigade, and provost-marshals and senior chaplains, and the army was far too large to see on a single morning or even march on a single road. Wellington, perforce, had become remote. There were bureaucrats with the army, defenders of files, and soon, Sharpe knew, a man would be less important than the pieces of paper like that folded, forgotten gazette in Whitehall.

‘Sharpe!’ Major Forrest was shouting at him, waving, hurrying over the rubble. He was leading a small group of men, some of whom carried a door, Lawford’s stretcher. ‘What happened?’

Sharpe gestured at the ruin about them. ‘A mine, sir. He was caught by it.’

Forrest shook his head. ‘Oh God! What do we do?’ The question was not surprising from the Major. He was a kind man, a good man, but not a decisive man.

Captain Leroy, the loyalist American, leaned down to light his thin, black cigar from the flickering flames of the timber baulk. ‘Must be a hospital in town.’

Forrest nodded. ‘Into town.’ He stared in horror at the Colonel. ‘My God! He’s lost his arm!’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Will he live?’

Sharpe shrugged. ‘God knows, sir.’

It was suddenly freezing cold, the wind reaching over the breach to chill the men who rolled the Colonel, still mercifully unconscious, on to the makeshift stretcher. Sharpe wiped the sword blade on a scrap of Lawford’s cloak, sheathed it, and pulled the collar of his greatcoat high up his neck.

It was not the entry into Ciudad Rodrigo that he had imagined. It was one thing to fight through a breach, overcome the last obstacle, and feel the elation of victory, but to follow Lawford in a slow, almost funeral march was destroying the triumph. Inevitably, too, though Sharpe hated himself for thinking of it, there were other questions that hung on this moment.

There would be a new Colonel of the South Essex, a stranger. The Battalion would be changed, maybe for the better, but probably not for the betterment of Sharpe. Lawford, whose own future was seeping into the crude bandages, had learned to trust Sharpe years before; at Seringapatam, Assaye, and Gawilghur, but Sharpe could expect no favours from a new man. Lawford’s replacement would bring his own debts to be repaid, his own ideas, and the old ties of loyalty, friendship, and even gratitude that had held the Battalion together would be untied. Sharpe thought of the gazette. If it was refused, and the thought persisted that it might, then Lawford would have ignored the refusal. He would have kept Sharpe as Captain of the Light Company, come what may, but no longer. The new man would make his own dispositions and Sharpe felt the chill of uncertainty.

They pushed deeper into the town, through crowds of men intent on recompense for the night’s effort. A group of the 88th had hacked open a wine-shop, splintering the door with bayonets, and now had set up their own business selling the stolen wine. Some officers tried to restore order, but they were outnumbered and ignored. Bolts of cloth cascaded from an upper window, draping the narrow street in a grotesque parody of a holiday as soldiers destroyed what they did not want to loot. A Spaniard lay beside a door, blood trickling in a dozen spreading streams from his scalp, while in the house behind were screams, shouts, and the sobbing of women.

The main square was like a bedlam let loose. A soldier of the 45th reeled past Sharpe and waved a bottle in the Rifleman’s face. The man was hopelessly drunk. ‘The store! We opened the store.’ He fell down.

The French spirit store had been broken apart. Shouts came from the building’s interior, thumps as the casks were stove in, and musket shots as crazed men fought for the contents. A house nearby was in flames and a soldier, his red jacket decorated with the 45th’s green facings, staggered in agony, his back burning, and he tried to douse the flames by pouring a bottle over his shoulder. The spirit flared, scorched his hand, and the man fell, writhing, to die on the stones. Across the plaza a second house was burning and men shouted for help from its upper windows. On the pavement outside women screamed, pointing at their trapped men, but the women were scooped up by redcoats and carried shrieking into an alley. Nearby a shop was being looted. Loaves and hams were slung from the door, to be caught on outstretched bayonets, and Sharpe could see the flicker of flame deep inside the building.

Some troops had kept their discipline and followed their officers in futile attempts to stop the riot. One horseman rode at a group of drunks, and flailing down with a scabbarded sword, split the group apart, and rode out with a young girl, screaming, clinging to his saddle. The horseman took the girl to a growing huddle of women, sheltered by sober troops, and turned his horse back into the melee. Shrieks and screams, laughter and tears, the sound of victory.

Watching it all, in silent awe, the survivors of the French garrison had gathered in the centre of the plaza to surrender. They were mostly still armed, but submitted patiently to the British troops who systematically worked their way down the losers’ ranks and pillaged them. Some women clung to their French husbands or lovers, and those women were left alone. No one was taking revenge on the French. The fight had been short and there was little ill will. Sharpe had heard a suggestion, floating as a rumour before the assault, that all surviving Frenchmen were to be massacred, not as revenge, but as a warning to the garrison at Badajoz what to expect if they chose to resist in their larger fortress. It was no more than a rumour. These French, silent in the midst of rampage, would be marched into Portugal, over the winter roads to Oporto, and then back by ships to the foetid prison hulks or even the brand new prison, built for prisoners of war, in the bleakness of Dartmoor.