Полная версия

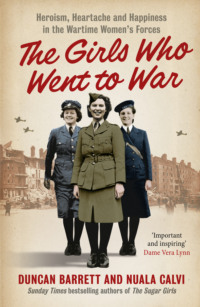

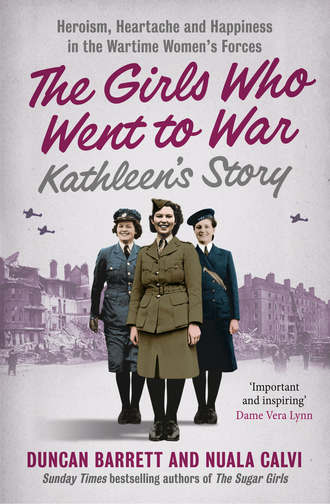

Kathleen’s Story: Heroism, heartache and happiness in the wartime women’s forces

She had seen a newspaper advertisement calling on women to join up with one of the three armed forces. With her love of the sea, Kathleen was particularly attracted to the idea of the WRNS, and she hoped that joining the Navy might offer the chance to visit some of the exotic places she had read about as a child. It didn’t hurt that, of all the women’s forces, the WRNS had by far the most stylish uniform.

Kathleen wrote to the address given in the paper, and soon received some forms to fill in. A week later she was invited to attend an interview at her local recruiting office. There she was grilled by a man and woman dressed in the smart blue uniforms of naval officers. They asked her about her health, qualifications and any relevant experience she might have – as well as some rather surprising queries about boyfriends and personal hygiene.

Kathleen answered the string of questions as best she could, doing her best to impress upon her interviewers how desperate she was to do her bit for her country. There was no getting around the fact that the skills she had picked up nannying weren’t exactly transferable to anything she might be expected to do as a Wren, but her obvious enthusiasm must have won them over. ‘All right, we’ll try you out,’ the woman announced at last. Kathleen couldn’t have been more thrilled.

‘You’ll have to pass a medical exam,’ the Wren officer continued, ‘but I’m sure you’ll have no trouble there. If you’re used to running around after young children you must be reasonably fit.’

The medical was to take place at a local doctor’s surgery in Tenby, and Kathleen asked her employer if she could have a few hours’ off to attend. She knew that competition for the WRNS was tough, and the medical standards for entry were high – generally only those passed as Grade I were accepted.

Kathleen was in good shape and she performed well in the physical tests, bending down, spinning around and walking along a chalk line to prove that she did not easily get giddy, and assuring the doctor that she wasn’t prone to seasickness. By the end of the examination, she felt confident that she had passed, and eagerly awaited her results.

At last the doctor came out to see her. ‘Grade I,’ he told her approvingly, looking up from a clipboard he was holding.

Kathleen jumped up from her seat, smiling, but the man put his hand out to stop her. ‘I’m afraid I can’t pass you, though,’ he said.

‘Why not?’ she demanded.

‘You’re too thin,’ the doctor replied. ‘The minimum for the WRNS is six stone, and you’re a few pounds under. I’m sorry.’

He turned and walked away with his clipboard under his arm, leaving Kathleen utterly gobsmacked. She had passed all the fitness tests, she had proved her worth. Yet for the sake of a few pounds her dream of serving in the Navy had been thwarted.

Dejectedly, Kathleen returned home and began preparing the baby’s dinner, staring longingly out of the window at the sea.

Chapter 2

Being rejected by the WRNS had been a bitter disappointment for Kathleen, but she wasn’t going to let it stop her doing her bit for the war effort. If the Navy wouldn’t take her now, she reasoned, she would just have to find something else to do until it was ready for her.

She had seen posters in town calling on women to join the Land Army – ‘for a healthy, happy job’ as they put it. The pictures showed girls standing in golden fields of corn, tilling the soil, gathering hay and tending to cute farm animals. The life of a land girl looked distinctly appealing, and even if the work was hard, the camaraderie would surely make up for that.

Kathleen handed in her notice with the family she was nannying for in Wales, telling them she was going back home to Cambridge. She was sorry to say goodbye to the little girl she had been looking after, but she felt it was for the best. The child was beginning to grow so attached to her that many people seeing them out together assumed she was her mother.

Once she got home, Kathleen lost no time in presenting herself at a recruiting centre, where she was interviewed by a rather superior woman who wanted to know if she had a farming background.

‘Well, I used to help my father grow vegetables in the garden,’ she replied, hopefully.

‘Horticulture for you then,’ the woman declared. ‘You’ll get your call-up soon, so be ready.’

A week later, Kathleen was on the train to Bury St Edmunds, ready to take up her first posting. She arrived at the station to find a rather luxurious-looking car waiting for her, along with a chauffeur who introduced himself as Bradley. ‘I’ve been sent to collect you,’ he explained.

Kathleen got in, wondering what kind of farm had its own chauffeur. They headed out into the countryside for a while, before turning up the gravel drive of a grand mansion, whose once carefully manicured gardens had been given over to food production.

A dumpy woman with rosy cheeks and white hair met Kathleen at the door. She looked awkwardly at her, as if she didn’t quite know how to address her. ‘I’m Mrs Jones, the cook,’ she said, shaking Kathleen’s hand and half-curtseying at the same time. ‘I’ll take you up to yer room.’

‘Thank you,’ Kathleen replied, following the other woman into the house. She admired the magnificent entrance hall and the broad, sweeping staircase carpeted in red velvet. Kathleen had imagined the land girls would all bunk together in a barn, sleeping on bundles of hay, yet it sounded as if she was to have her own bedroom, right inside the grand house itself.

Kathleen’s room turned out to be at the very top of the building, and it was small but tastefully decorated. ‘You’ve got a lovely bathroom along here,’ Mrs Jones said, showing her into a large room with decorative tiles around the walls and the deepest bathtub she had ever seen. ‘Well, I’ll leave you to get settled,’ she told her.

‘Thank you,’ replied Kathleen. ‘Just one thing – where are all the other land girls?’

‘There ain’t none,’ the cook replied. ‘You’re the first we’ve had.’

Kathleen couldn’t help feeling disappointed. She had imagined herself making friends in the Land Army, going to dances with the other girls in the evenings and sharing confidences late into the night. Yet here she was, entirely on her own. It didn’t help that the servants seemed unsure how to treat her, since her status was somewhat unclear. She certainly wasn’t on the same level as the aristocratic family of the house, yet she wasn’t really one of the staff either.

That evening Kathleen’s dinner was sent up to her on a tray and she ate it alone in her room. But after she had finished, she decided to head downstairs and try to break the ice. In the basement she found the servants’ sitting room, where some of the maids were drinking tea. As she entered, they instinctively jumped to attention.

‘Oh, please don’t get up,’ Kathleen insisted. ‘I thought maybe I could join you for a while.’

The maids looked at her a little uncertainly, but one of them, a pretty ginger-haired girl a few years younger than Kathleen, gestured her towards a chair. ‘Course you can,’ she said. ‘I’m Minnie. How d’you do.’

Kathleen introduced herself and sat down opposite Minnie. ‘Do you play cards?’ the girl asked her.

Kathleen nodded.

‘How about Beat your Neighbour out of Doors?’

‘I’ve never heard of that one!’ Kathleen laughed.

‘Don’t worry, I’ll teach you,’ Minnie said, doling out the cards to Kathleen and the other girls. Soon they were all engrossed in the game, their former awkwardness forgotten.

Kathleen liked Minnie, and she soon discovered that the two of them had a lot in common. Minnie’s father had been stationed with the Army in India, just like Kathleen’s dad, and she had spent her early years living abroad.

As they played, Kathleen couldn’t help noticing that one of the other kitchen maids’ hands were badly disfigured, the fingers stuck together and the thumbs missing. ‘My mum fell off her bike when she were pregnant with me,’ the girl said, seeing her staring.

‘Oh, I’m sorry,’ Kathleen replied. ‘How awful.’

The girl shrugged. ‘Stopped me bein’ called up, though, so that’s somethin’.’

Mrs Jones wandered in from the kitchen. ‘You lot better let Miss Skin ’ere get to bed,’ she told the other girls. ‘She’s got to be up at ’alf five to help Mr Shaw, you know.’

Kathleen was shocked – that was even earlier than in her old job as a nanny. But there was no time to protest, as Mrs Jones gave her a candle to take up with her.

‘Oh, this arrived in the post for you,’ the cook added, handing her a parcel. ‘I reckon it must be your uniform.’

The next morning Kathleen was awoken by a knock on her door, and one of the maids came in with a cup of tea for her. It was still dark outside as she struggled into her new uniform – a fawn shirt, green V-neck pullover, brown corduroy breeches and long socks up to her knees. It was hardly a glamorous combination, but worst of all were the shoes – brown leather so hard that it felt like she was putting her feet into clods of iron.

Down in the kitchens Kathleen found Mrs Jones, who showed her the way to the gardens. Dawn was just beginning to break, and as Kathleen stepped outside she spotted a tiny old man with a bald head motioning to her to follow him. She guessed that the gnome-like figure must be Mr Shaw, the gardener.

The old man led Kathleen into an orchard of apple trees, where every spare inch of ground had been planted with vegetables. ‘Shu’ geh,’ he called back over his shoulder.

Kathleen looked at him blankly.

‘Shu’ geh,’ he repeated, more emphatically.

‘I’m sorry, what does that mean exactly?’ Kathleen asked, confused.

The little man walked slowly back over to the gate and pulled it shut behind her. ‘Shu’ geh,’ he repeated for a third time, clearly exasperated.

Mr Shaw hailed from Yorkshire and made no concessions to Southern ears like Kathleen’s. But as he showed her around the gardens, she realised he was a kind soul really. He had a daughter her age in the ATS, he told her, and he and his wife worried about her terribly.

Mr Shaw explained that thanks to the war he now grew everything from potatoes and turnips to broccoli, cabbages, kale, sprouts, carrots and mangold wurzels, all of which were sold at market in town. There were also apple, pear and plum trees, as well as bushes of gooseberries, raspberries and redcurrants. ‘Now, you jus’ do what ye can,’ he told Kathleen, handing her a spade and looking at her skinny frame uncertainly. ‘I don’t expect too much of ye.’

At Mr Shaw’s instruction, Kathleen set to work digging and planting, determined to prove to him that she was more than capable of the job she had been sent to do. But after an hour or so her brow was dripping with sweat and she felt ravenous.

She was relieved when, at eight o’clock, they stopped for a breakfast of porridge. ‘When do we finish for the day?’ she asked Mr Shaw.

‘Why, when t’sun goes down!’ the old man said, with a chuckle.

Soon they were back at work again, digging and hoeing away until at last Mrs Jones rang the bell for lunch. Kathleen took her meal on her own, while Mr Shaw headed back to the gardener’s cottage to eat with his wife.

By mid-afternoon Kathleen was utterly exhausted, but as Mr Shaw had promised there was no stopping until dusk fell. The vegetables had to be got ready for market on Monday, he told her, and with only a tiny old man and a skinny young girl to get it all done, it was going to be quite a task.

By the time Kathleen went up to her room that evening she was barely able to stand from the physical exertions of the day, and she woke the following morning feeling as if every muscle in her body had been pulled. It hurt just to walk down the stairs, but there was nothing for it except to head out to the gardens and start digging all over again.

The days at the grand estate passed excruciatingly slowly, and for Kathleen, who loved to talk and laugh, it was a lonely time. She was often left on her own for hours while Mr Shaw worked elsewhere in the grounds. Much of the time her only company was an old Suffolk horse called Patsy who, like the gardener, had seen better days.

One evening, Kathleen had just returned to her room to change out of her muddy clothes when there was a knock on her door. ‘Come in,’ she called, sitting down on the side of her bed.

Minnie came tumbling in excitedly. ‘You’ve been asked to go to dinner,’ she announced.

‘Where?’ Kathleen asked her, confused.

‘Here, with the family,’ the girl explained, grinning. ‘They want you to join them in the drawing room first – for sherry!’

‘Oh, right!’ Kathleen exclaimed. She hastily put on her only decent-looking dress and followed Minnie downstairs into the grand drawing room.

There, the lady of the house, Mrs Ashbourne, and her youngest daughter were waiting to receive her. The mother was a tall and elegant woman and her daughter was pretty, although Kathleen thought she looked rather tired.

‘So, you’re our new land girl,’ Mrs Ashbourne said, eyeing Kathleen with interest. ‘How delightful. And how is old Shaw treating you – not too roughly I hope?’

‘Not at all,’ Kathleen answered. ‘He’s been very kind.’

‘I’m so glad,’ the lady continued. ‘My daughter Jane here works as a nurse in the local hospital, you know. It’s terribly hard work, but the young must do their bit for the war, I suppose.’

Jane looked up and gave Kathleen a feeble smile.

Looking around the room, Kathleen saw that it was hung with a number of old oil paintings depicting the family’s ancestors. Mrs Ashbourne was delighted to talk her through them all, introducing each long-departed family member one by one. From what Kathleen could gather, the Ashbournes, along with most of the other wealthy families in the area, were Quakers. They had all made their money in manufacturing, and by now they had intermarried pretty thoroughly.

At dinner, however, it was Kathleen’s family that was the object of conversation. The Ashbournes had never had anyone like her sit at their table before, and they were fascinated by every detail of her life when she was growing up. Story-telling was Kathleen’s forte, and she warmed to the task, entertaining them with tales of her parents’ romantic meeting in Cape Town and the struggles they had faced coming back to England, where they had survived on the rabbits they caught and skinned for dinner. The whole family hung on to her every word – in fact, the only difficulty she faced was trying not to giggle when the servants she had been playing cards with the night before winked as they served her potatoes.

After dinner, Kathleen snuck back down to the basement for a cup of tea with the maids and listened to them gossip about the family. ‘They’ve got 12 children, you know, and at least two of them are doolally,’ Minnie told her.

‘They say the Ashbournes are running out of money,’ the girl with the deformed hand chipped in. ‘It was all invested overseas, and now they can’t get it ’cos of the war.’

‘And as for that Jane,’ the head housemaid, a woman of about 40, added, ‘I’ve heard she’s in love with one of the wounded soldiers she’s been treating down at the hospital – and it turns out he’s a lorry driver in Civvy Street!’

‘Ooh, I don’t think madame would be too pleased about that!’ declared Minnie. The group of women laughed together until their sides ached.

Kathleen enjoyed the chance to join in with the servants’ gossiping, but she soon discovered that the head housemaid had a romantic secret of her own. That night, when Kathleen tiptoed down to the kitchen to fetch herself a glass of water, she found the woman perched on the kitchen counter with her legs wrapped around the postman.

Kathleen gasped, and the couple sprang apart in embarrassment. As the postman hastily picked his trousers up off the floor, she backed out of the room, blushing, and fled up the stairs.

Kathleen’s own love life was continuing as well as could be expected with her boyfriend hundreds of miles away up in Scotland. She and Arnold continued writing to each other regularly, and she kept him up to speed with all the strange goings on at the grand house. But it wasn’t long before she had a new and entirely unwanted admirer to deal with.

The fields neighbouring the Ashbournes’ estate were owned by a young farmer who had recently inherited them from his father. He had several land girls working for him already, but when one of them fell ill he asked Mr Shaw if he could borrow Kathleen for the day to help harvest his Brussels sprouts.

‘Aye, ye can ’ave the girl,’ the old man replied, ‘but only if ye promise not to overwork her. The poor lass is thin as a rake, you know!’

Kathleen set off, happy for a change of scene and hoping to get to know some of the other land girls. But she soon discovered she would be spending the day all alone in a ten-acre field, her only visitor being the farmer. The young man took a keen interest in the flame-haired girl who was picking his sprouts, and stopped to stare at her whenever he passed by on his tractor.

It didn’t take long for him to find an excuse to come and talk to her. ‘You be a pretty little thing to be getting your hands so muddy,’ he remarked admiringly.

‘Oh, I don’t mind,’ Kathleen replied, carrying on with her work.

‘Got a boyfriend, have you?’ the man asked her.

‘Yes, I have,’ said Kathleen, firmly.

‘That be a shame,’ the man told her wistfully. ‘I been looking for a wife to run this ’ere farm wi’ me.’

Kathleen said nothing, and eventually the man went away. But over the next few weeks he kept asking Mr Shaw if he could ‘borrow’ her again. The young man was clearly lonely and longed for someone to share his days with, but Kathleen soon grew sick of him pestering her.

One day, the young farmer took Kathleen with him into Bury St Edmunds, where he had some errands to run. She sat in the passenger seat of his van, wrapped up in her own thoughts and doing her best to avoid conversation.

Suddenly there was an almighty crash as the van collided with another vehicle. Kathleen was thrown from her seat and her head smashed straight through the windscreen, lodging there as the van came to a halt. Her neck was completely surrounded by glass, and it was cutting painfully into her skin. If she moved even an inch, she was sure it would sever an artery.

Before long the police were on the scene, carefully dismantling the windshield around Kathleen’s head and freeing her from the prison of glass. She was rushed to the local hospital, where her cuts were bandaged up, but the accident left her with a ring of tiny scars around her neck.

Before long, the case came to court, and Kathleen was called as a witness. The young farmer was claiming that the other vehicle had come out of nowhere when he hit it, and she was asked what she remembered of the incident.

‘I’m sorry, but I can’t help you,’ she replied. ‘I just don’t remember a thing.’

‘You must have seen what happened,’ the magistrate protested. ‘You were sitting right up in the front!’

But Kathleen had been so busy daydreaming that she had no recollection of anything before the moment her head hit the glass.

The young farmer was duly fined for dangerous driving, and after Kathleen’s failure to corroborate his account, he never asked her to pick his sprouts again. It was scarcely the easiest way to free herself from his unwanted advances, but it seemed to have done the trick nonetheless.

It was many months now since Kathleen had last seen Arnold, but his letters had kept her going through the long, hard days on the land. At last, when she went home to her mother’s house in Cambridge for some leave, he was able to join her for a day. To Kathleen he seemed even more charming than she remembered, and her feelings for him were stronger than ever before.

Mrs Skin did everything she could to make her daughter’s handsome officer welcome, using up an entire week’s rations on a single magnificent meal. But it was when she finally went out on an errand that Arnold revealed the true purpose of his visit. ‘My darling,’ he said breathlessly, taking Kathleen in his arms, ‘you know we belong together. Will you marry me?’

Kathleen felt as if her heart could have burst then and there. ‘Yes, of course!’ she cried, falling into his embrace.

Arnold drew a little box out of his pocket and handed it over to her. Inside was the most beautiful ring that Kathleen had ever seen, set with a stone of yellow citrine. He tried to push it onto her finger, but to her disappointment it just wouldn’t fit. ‘Oh dear,’ he murmured. ‘I suppose we’re going to have to get it altered.’

‘No – don’t take it away,’ Kathleen pleaded. ‘I’ll wear it around my neck on a chain. That way it’ll always be with me when we’re apart.’

Kathleen hoped it wouldn’t be long before the two of them could be married, but to her surprise Arnold told her that he wanted to wait until the war was over. ‘I’ll never forget the woman who used to wash our steps and windows,’ he told her. ‘She had been wealthy once, but when her husband was killed in the last war she was left with two young children to support by herself. I wouldn’t want that to happen to you, my dear.’

‘Yes, of course, you’re right,’ Kathleen replied, trying to hide her disappointment. If it was up to her, she would have married Arnold then and there, but she was willing to abide by his decision.

After Arnold had left, Kathleen showed her mother the ring. ‘I knew it!’ Mrs Skin declared, ecstatically. ‘I just knew that you’d be married before the year was out! Oh isn’t he wonderful, Kath. What a lovely man you’ve found yourself! I’d better start seeing about your trousseau.’

‘We’re not getting married until after the war, Mum,’ Kathleen protested weakly. But it was no use reasoning with her mother. Mrs Skin was already off to tell all her friends, and gather material for her daughter’s bottom drawer.

Chapter 3

After many months in the Land Army, Kathleen’s body had gradually grown stronger and more resilient as she adapted to the rigours of 12-hour days working the land. Now she was determined to try again with the Navy, so she said her goodbyes to Minnie and the rest of the staff in the strange old house at Bury St Edmunds, and took a train down to London. There she made her way to the national headquarters of the WRNS, which was housed above Drummond’s Bank in Trafalgar Square.

But despite her best efforts to convince the women there that she was just what the service needed, they insisted that there still wasn’t a place for her. ‘I’m sorry,’ one of them told her, ‘but we’ve just got too many people volunteering at the moment. Maybe you could try again in another six months.’

Kathleen was disappointed at being turned down by the WRNS for a second time, and it was especially galling to think that while she had been waiting to reapply, other girls had taken the available places. But she couldn’t bear the thought of heading back to the house in Bury with her tail between her legs, so instead she began looking for war work in London.

Before long, Kathleen had swapped the jumper and breeches of a land girl for the blue overalls of an ambulance auxiliary. It was far from the high couture of the tailored Wren uniform that she had long coveted, but at least, she reasoned, the new job would bring with it different challenges – and, hopefully, less back-breaking work.

Since she didn’t drive, Kathleen was paired up with a girl who did – a young woman called Hilde with whom she was soon sharing a small flat in Chiswick. The two girls hit it off instantly, and when Kathleen learned Hilde’s sad story it only cemented the bond. ‘My husband walked out as soon as he found out I was pregnant,’ Hilde confided one evening, explaining that her daughter Joy was now living with a family in the countryside while she worked on the ambulances to support her.

Hilde and Kathleen’s ambulance – in reality a converted van – was based at the offices of United Dairies in Chiswick, a location they came to know extremely well as they spent night after night there sitting around waiting for the phone to ring. The other volunteers included several members of the same family, who had all volunteered together and were all actors. Kathleen and Hilde soon grew used to being hugged and kissed effusively whenever they came into the office, and to being addressed exclusively as ‘darling’. More of a trial were the histrionic rows between the father and his eldest daughter, which seemed to erupt on a daily basis and frequently descended into furious swearing matches.