Полная версия

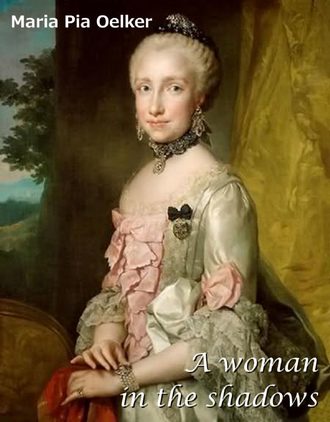

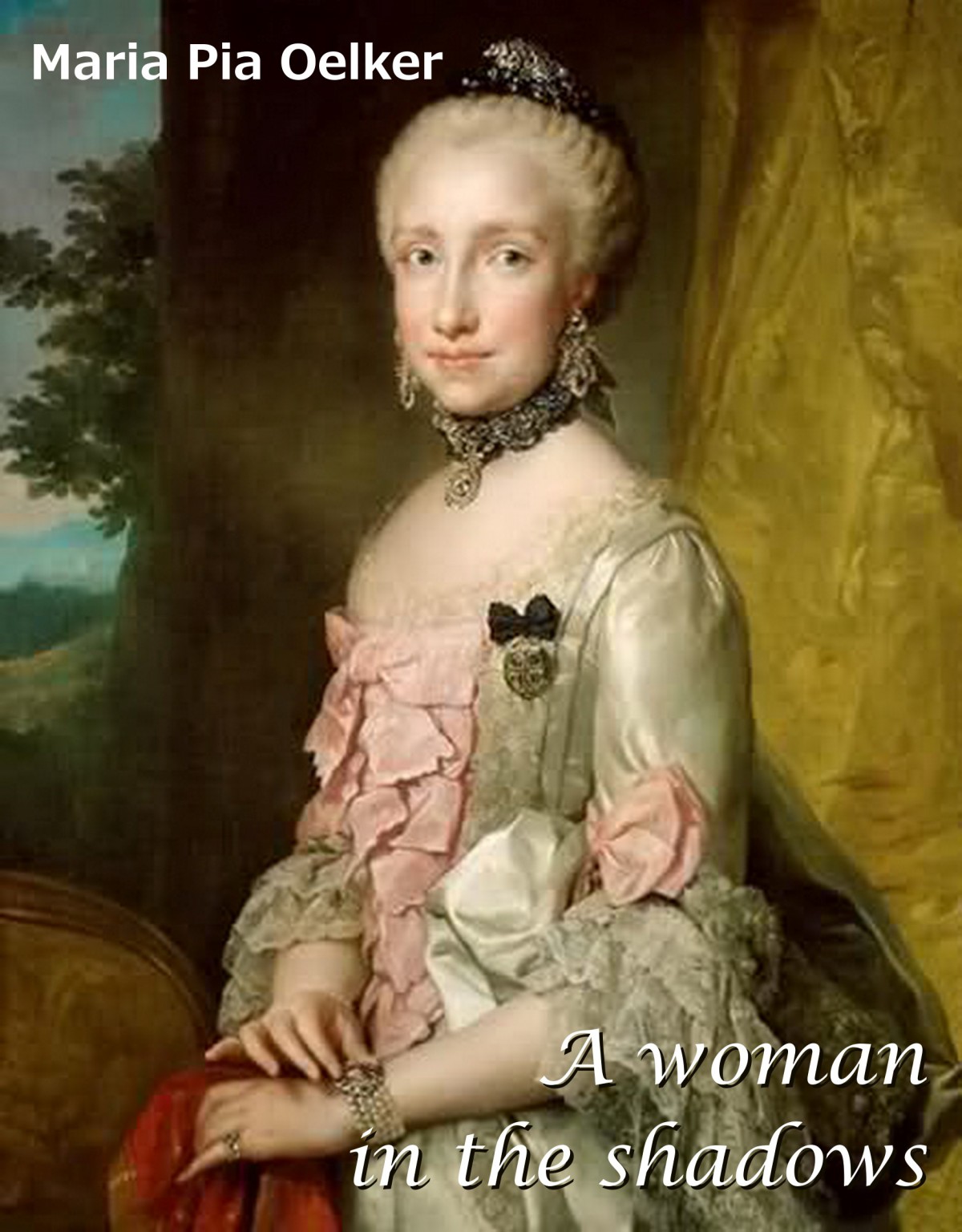

A Woman In The Shadows

Maria Pia Oelker

A woman

in the shadows

A WOMAN IN THE SHADOW

Translated by: Martyn Fogg

Publication date: June 2017

Publisher: Tektime

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Posthumous notes by the author

Chapter 1

He now seemed to be sleeping peacefully, after a night and a morning with a high temperature that had come on suddenly. In the half-dark large room, I was left alone with him, except for the presence of a nurse, and I had sat near the window to do my embroidery. My thoughts were like the clouds, almost completely covering the winter sun on the roofs of Vienna, melancholy and cold.

I watched him while his face, still red from the fever, was almost hidden among the puffed-up cushions on the bed: his hair had lost almost all the blond of his youth, his eyes for some time were permanently encircled by thick dark rings, left by the innumerable worries that every day, every hour, beset him incessantly.

I remembered again the first time I saw that face, still very young, depicted in a medallion decorated with pearls and precious stones. I had looked at it for several minutes with curiosity and a few goose pimples, studying the elongated oval face, the serious and deep-set eyes, the slim nose and the high and thoughtful forehead and I gave a sigh of relief: he was rather nice and I wondered if one day I would manage to even love him or at least feel a certain affection for him.

I knew no-one was expecting us to love each other, it was not a thought that at all disturbed the sleep of our august parents, the sovereign rulers of two powerful states; the main issue was the alliance between two one-time enemies, the sharing of power and dominance over Europe, sanctified by that marriage, as well as by international treaties.

Almost twenty-seven years had passed since our wedding and that time seemed to me to have flown by in a flash, in an intense life, lived to the maximum, day after day.

While my hands worked quickly and distractedly, that day I inexplicably felt my life was in the balance and I did not know if I was ahead or losing.

I smiled thinking of how many times over the years I had heard that word which was certainly not usual, neither at my father’s Court nor in most of the other European courts and which was instead a source of continual and heated discussion at Pitti or Poggio Imperiale palaces. I felt shivers of cold running down my spine and I pulled around my shoulders the wool and silk shawl that my husband liked so much for its aquamarine colour, which was his favourite

I heard him move slightly. I turned towards the bed and saw his face contract in a slight grimace of pain. He was still asleep, but I do not know why he did not seem to me to be as calm as he was a few minutes earlier. I got up and approached him. I put my hand on his forehead and felt it burning. In that precise moment, he opened his eyes, looking almost bewildered, he called me and tried to get up, shaken by dry heaving. . I put my arms around him, I said: “Calm down, it will be all right”, while the nurse ran to help me and hold him up. He gave a last glance at me, a gasp and then nothing.

I looked at him incredulous, appalled, incapable of truly realising what had happened.

He no longer responded, his heart had stopped beating. There was nothing more man could do for him.

“Now”, I thought, “only God can take care of his generous spirit.”

Everything had happened so suddenly, that I could not manage to even think. I left the others to deal with him, watching them, as if they were acting in a dream, sure that I would then wake up suddenly and find him and our children again, like every day, filling my life.

But I did not wake up and, a little bit at a time, I began to finally understand what had happened. My husband was dead, I had become the widow Empress, my son was the new Sovereign.

I understood, but I could not manage to accept it.

I suddenly had the impression that a part of me, perhaps the best and most alive part, had gone away for ever.

There was now not a moment during those terrible days, when I did not ask myself, with exasperating monotony, what I had really been for him. I mean to say that I, as a woman for him as a man.

He had been an energetic, untiring and intelligent sovereign; I had been his wife, the mother of his children, but what else? What had our marriage really been? A rhetorical question, perhaps, but essential for me: it was no longer enough for me to know that we had simply played the roles chosen for us by others, when we were still adolescents, ignorant of the world, which moved disturbingly, and often dramatically, around our palaces, parks and gardens, the sparkling salons, the parties, the villas, our easy and rich lives, I wanted the truth, even if nobody could have ever been able to easily give it to me. Me less than others.

I was 14 years old, when my father, Carlo, left Naples, where I was born and had spent my infancy and early adolescence, to go to Spain and take over the throne. My brother, some years younger than me, stayed in Italy: he would become King of Naples, even though he then thought only of toys, like a real baby, spoilt and very free. They told me, almost immediately, that I would marry an Austrian archduke, the son of Maria Teresa of Hapsburg. I had been educated to accept my father’s decisions, without discussion or objections: that choice, anyway, left me astonished, at the very least: but were the Hapsburgs our enemies? We had been fighting them for a long time, I had been taught, my father had taken over from the Austrians in the reign over Naples and we had lost a lot of territories, even the Italian ones had gone to the Imperial dynasty; anyway, I also knew that political reasoning did not follow any apparent logic, nor even less so, the reasoning of the heart; for the rest, if it was normal for every woman to accept the husband chosen by her family, it was so much more so for whoever, like me or my sisters or cousins, was not mistress of her own life, which belonged entirely to the State. An instrument for perpetuating a dynasty, useful to make and unmake alliances.

We talked about it between ourselves, in our secret rooms, sometimes with melancholy, other times with bitterness and impatience, according to the characters, consoling ourselves with the hope of, anyway, experiencing one great love to fill us with its exciting exhilaration. Keep up appearances, this was essential, carrying out our official function was indispensable, then - Perhaps one could find some small opening for a private life. We found them all.

It was not a great victory, but it served to maintain some shred of a dream, some residue of sweetness, to support a life beside unloved men, chosen by others, often unpleasant and domineering, occupied in intrigue and incessant wars, taken with themselves and their ambitions. In a court full of traps, conspiratorial whispers, friends/enemies, cheats and imposters.

I did not manage in time to get used to the idea of this Austrian husband, with whom I would have to live and reign in Tuscany (but where was Tuscany? I barely knew), when the tragic news came: he had died of smallpox. The plans had to be substantially changed: I would marry the younger brother, Pietro Leopoldo, who, in turn, would have given up the wife always promised to him, Beatrice d’Este. He was a year and a half younger than me, but everyone said that he was exceptionally mature for his age.

The game of chess started up again, for the umpteenth time: the chancellors started again discussing, sending despatches, evaluating the pros and cons, proposals and counter-proposals, in a mad, absurd and very natural merry-go-round.

Territories and peoples, marriages and nuptial agreements, financial clauses and ceremonial arrangements, etiquette and government, all in the same cauldron. It has always been like that and there was no reason to change it, if the mechanism worked perfectly, tested over centuries of dynastic history.

Together with our nannies’ milk, we had sucked in this simple concept: we are pawns in a game that is bigger than all of us, we have to subordinate our personal wishes to that which the family had decided in the supreme interest of power.

In reality, when I was sixteen or eighteen years old, I did not know anything about concepts like personal aspirations, free will or things of that kind. None of my teachers or tutors had taken the trouble to even mention it to us. To my brothers, one destined for the Naples throne and the other to that of Spain, perhaps (I say perhaps and not by chance) something had been said, but not to us women, no. Only many years later, did I hear talk of my husband and his friends and, even though I had to initially make a considerable effort to follow them in their discussions and reasoning, it was a source of pride for me to understand and I ended up becoming very impassioned by those discussions. In my adolescence, ignorant of big philosophical matters, the problems which hounded me were very different, in common with my noble female friends and cousins. Who will I marry? Will he be a pleasant or an absolutely odious life companion, kind or overpowering, intelligent or stupid, vacuous and ignorant?

Will he like me, notwithstanding that my looks are not among the most fascinating?

We spent hours taking care of our clothes and our manners. We knew how to dance and gracefully take part in conversation. I had been taught French and I had a very basic knowledge of German (notwithstanding it was my mother’s native tongue); Italian, which was the language of culture and art, I had known since I was little, even though my teachers did not manage to take away my Neapolitan accent, which according to them did not go down at all well. When I then learned that I would be going to Florence, they redoubled their efforts to refine my diction, but in vain, I fear: I never managed to adopt that sweet elocution that they used in Tuscany.

From the alchemy of my father’s advisers, there finally emerged the dates and names, which would define the course of my future life. I would therefore marry the third son of the Hapsburg Lorraine house, the Archduke Peter Leopold, first at Madrid by proxy, then at Innsbruck. The date fixed for the religious marriage was the 5th of August 1765.

I knew nothing about Peter Leopold, or almost nothing, at the moment I left for Genoa and from there for Austria.

Or better, about him as Archduke and future Grand Duke of Tuscany, I had been given all the information possible, from the detailed history of his imperial family, to his studies, his culture (always and only the official virtues, you understand, not his weaknesses or his personal inclinations). I had a portrait of him that had been sent from the Imperial Court and that I wore, set in a pearl bracelet, on my wrist. But I knew that then, in person, he would necessarily have looked different. For the rest, when I had been able to see the portrait done for me by the court painter, ready to be sent to Vienna, I had to admit that, even he would be surprised: I was really not so angelic and, if my blond hair was not bad and my physique could be considered to be well shaped and elegant (I was also rather vain about my clothes, I admit), my face was not particularly seductive.

I was not good at making myself look more attractive through make-up, perhaps because, in reality, I hated plastering myself too much and preferred more natural-looking faces.

My girlfriends sometimes looked like grotesque masks and I did not understand how they could believe they looked more attractive with all that white and that red and lipstick Among other things, my delicate skin itches for days and days, when I give in to their insistence and let myself be convinced to follow the fashion. In this way, if I could, I would willingly do without it, but the general effect, I must admit, was rather dull. The honest and cruel mirror gave me back the image of a face too long, with a significant nose and not very big eyes. Let’s be frank: I did not like myself and I was convinced that I also would not have made a good impression on my husband, I certainly would not have enchanted him and this made me nervous. I would have wanted a wedding dress rich in precious decorations and hoped that at least that would have enhanced a little, if not the aesthetic look, at least my morale.

I knew that he would have been accommodating and we would have seen each other for the first time only some days after the wedding, just for a few hours, that is to say that I would not even have had the possibility to fascinate him at least with my spirit, which everyone said was lively and sparkling.

For the sake of argument, let’s say that my education, just average for a noble-woman, according to the norms of the era and, in particular, those of Spain, could stand comparison with Leopold’s. Everyone talked about him as a boy in love with knowledge and science, a student of law, economics and philosophy They said that he was very serious and mature for his age, that, even before being installed on the Tuscan throne, he had already learned in detail about the situation of his realm.

I had recently given myself a lot of work, reading and studying, arousing ironical perplexity among my ladies-in-waiting and cousins, who suggested other more mischievous routes to conquer the heart of a husband, but I did not know if I could have been able to maintain a learned conversation with him.

And, moreover, since he was a baby, Leopold had been brought up and educated to be a sovereign, but not I; no-one expected me to be well-educated and informed like a man, rather some judged it to be useless, if not inconvenient, even my love of books.

There were only a few days left before our departure. Everything was ready by now and I did nothing but cry at the thought of leaving my palace: for the second time in my life, I had to abandon familiar places, friends, life-long habits and, this time, to go to marry a man that I did not know, from a country and a culture different from mine. Having grown up in a Nordic country where snow fell in winter and the sun showed itself only a little for many months of the year, where there was no sea (had he ever seen the sea?) and the bright and splendid colours of the Mediterranean natural environment. Who knows if he was like his country, which I imagined cold and melancholy, full of rainy darkness.

Someone said that Leopold was sensitive and good, even if a bit too withdrawn, but they were rumours, not official reports.

What did they say about me?

That I would be a perfect wife, docile, kind, loving, that I was strong and healthy and I certainly would give him many children. That I would not cause trouble for him and would obviously put up with his private life without making any scenes, whatever it was, remaining always and in every circumstance, faithful and beyond reproach. That I have never loved any men and therefore came to him, not only a virgin (this was implied and moreover the nuptial contract testified to it solemnly and clearly), but pure and innocent also in my soul.

This latter thing was not completely true, but only I and my close girlfriend, Amalia, knew it, as I had confided to her my first and only adolescent love for a gentleman in my brother’s entourage.

A platonic love perhaps, but overwhelming and passionate; that did not let me close my eyes for entire nights and even brought me to become delirious about impossible elopement, rebellions infeasible under the court etiquette; which made me get agitated and cry ever more bitter and resigned tears, when I realised that, even if he had loved me, there could never be any bond between us and that I could never belong to any other man than the husband predestined for me, without contemplating a suicide consequent to a prohibited act of love.

In the moments of greatest tension of the frenetic preparations, I compared that far-away and unknown archduke, not particularly handsome, to my dark-haired lover with his large bright eyes, smiling mouth and musical voice and I believed I would explode with resentment towards everyone who had always decided on my life. Then I regretted it and tried to reason objectively and be resigned to it. I did not manage it very well, but I tried.

It was then that I swore to myself that, however things went, I would never pretend again in my life.

Now I can say with absolute certainty that I have maintained that vow.

One morning, in the month of June, while I was in the garden enjoying the coolness of the trees and the gushing fountain, a letter arrived for me.

It was from my future husband.

I opened it a bit annoyed, expecting rhetorical and formal words, that would have irritated me with their empty and dull sweetness.

The butler who brought it to me said that the prince had sent the message strictly in private by means of a trusted ambassador, who had implored him to only deliver it to me by hand.

I smiled condescendingly: it figures! A scene good enough to convince only fools. I was in a bad mood that morning and I was bound to judge anyone in a manner more than severe, almost acid and perhaps a bit cruel.

Anyway, I continued with the game and, graciously, sent away also my personal-ladies-in-waiting. They were bursting with curiosity about what was written, I knew, and I was maliciously pleased to delude them. I had no intention of telling them anything, not even later. In fact, after having read the message, I would not want to have shared the contents with anyone, but not for spite this time, for a sense of modesty. For the joy of keeping it only for myself, as a precious memory and token. Peter Leopold’s letter was kind, full of concern for me, of feelings so delicate that one could have said they had been written by a woman and not by a haughty Imperial prince. It was clear that he was as curious and anxious as me to have the decisive meeting, but also in anguish, nervous and insecure. Behind the courteous, but not formal, words, there was a sense of a desperate need to understand, realise and imagine the future. To justify what in reality did not need to be justified, because even he had had to accept, without any say in the matter, decisions which came down from on high.

Two closely-written pages with small handwriting, slanting and not too flowery. Well-balanced enough except for some individual letters that, here and there, seemed to have got out of control.

At the end, a little before the closing, there were some phrases that froze my heart for a moment, which already seemed to be a little calmed and cheered up at the evident discovery of a character so unusually sensitive.

Short but significant phrases: - “Do not give credit, I beg you, to what they say about my amorous adventures and above all about my love affair with Miss Erdody. By now the past, and what it meant for me, both in joy and the deepest and bitterest pain, no longer counts and I swear to you that I believe I will be your sincere servant.” -

Who was that lady? I had never heard her name, but evidently Leopold took for granted that some bad-mouthed person had told me about her. And why ever would I have had to be told about her. I did not have time to reply to him, because any letter of mine would have arrived about the same time as me and therefore it was better to keep back my questions for a more intimate and personal meeting, even though I doubted that I would have been able to overcome my shyness to ask him certain questions. On the other hand, I did not want to ask anyone else for particulars of that episode which he had mentioned, I did not like malicious gossip and Leopold had put so much shame and pain in that statement that I did not feel like expressing any kind of criticism.

Should I have rather confessed to him also “my” adolescent love for Don Felipe?

I finished reading that long letter, refolded it carefully and put it away in a pocket of my dress. I would not have shown it to anyone, not even my usual affectionate confidants.

It was for me only, I considered it almost a token of love. Although I knew that there really was not even one word of love in it, I wanted to delude myself that he who had written it had wanted to implicitly declare to me at least the full willingness to open his heart to me.

I was nineteen and a half years old and not a naive little girl by that time, although life at court, so easy and alien to any awareness of the real world, had not prepared me at all for future married life. Some wound not yet completely healed in my heart, by nature borne to give too much space to fantasies and feelings, anyway put me on the defensive.

In the evening, while in the suffocating heat of the bedroom I tried in vain to go to sleep, I looked out of the open window, through the light screen of the curtains, at the piece of starry sky above the patio and asked myself if the same stars shone in Austria and, with a smile: - Who knows if Leopold, not being able to sleep through agitation, is looking at them like me? -

I felt like a fool, but I also thought that that would have been the first thing that I would have told him.

I got up and went to the window to breathe in the strong and heady aromas of the garden in full summer flowering. I thought that it was one of the last nights that I would spend there and started to cry without knowing why. I called one of my personal maids and begged her to light the lamp on the small table.

- “Couldn’t you get to sleep, your Highness?” - she asked - “Do you want me to bring you something?”

- “No, thank you, I don’t need anything.” I’m just a little nervous, that’s all.”

She carried out graciously the task that I had requested and, before going away, asked me again if I really did not need anything to drink.

She was a woman of a certain age who had always been with me since I was a little baby who played thoughtlessly in the palaces and the Neapolitan villas, looking at the sea through the windows and enjoying the music which at times seemed to come out of nothing through the streets of Portici. I would have liked to take her with me, but she was not in the list of people of my entourage, who, in truth, would then have abandoned me at Genoa after the entry into the port and would not have followed me to Florence.

I decided that the next day, for the first time in my life, I would have an amazing tantrum to get what I wanted: a ladies’ personal companion to take to Italy. I was certain that my father would have satisfied me, I do not know why, but I was sure to succeed.

- “Would you be happy to come with me to Italy?”

- “Oh, your highness, certainly, but they have said that no Spanish lady will follow you.”

- “Right - I noticed a certain bitterness - nevertheless - anyway not to Naples, to Tuscany.”

- “I don’t know where it is, but if your Highness will be there, I would want to be there also.”

I knew that she sincerely liked me and I also, notwithstanding she was only an old governess, liked her. She was the only one with whom I could speak Italian with that Neapolitan accent of mine, so terrible for my teachers and thus dear to my heart.

- “I’ll try to have you placed on the list of my entourage, but I don’t know if I will succeed.”

She smiled.

- “you’ll be a delightful wife and Archduke Leopold will be a happy man.”

I thought: - “Not necessarily”. On the contrary, he probably won’t think so at all. Who knows if, when he sees me, he will compare me with his lost lover? Perhaps he will dislike me for having occupied a position that he would have wanted for another woman.