Полная версия

The Thirty List

No.

The ‘lovely room in modern flat with friendly city gent’ in Docklands turned out to be a nice place, if a bit ‘chrome and leather are the only decorative materials that exist, aren’t they’ for my taste, but I was followed round at a distance of three centimetres by Mike, the owner, who told me at least five times he didn’t need the money, like, he earned a packet in the City, but he wanted a bit of ‘feminine companionship’ round the place. No.

The ‘delightful double in house with fun girl’ turned out to be the living room, turned into a bedroom, in the flat of Mary from Camden, who handed me a list of her ‘house rules’ when I stepped in. First was, always take off your shoes when entering and put on special slippers, which were embroidered with cat faces.

No, no, no, hell no.

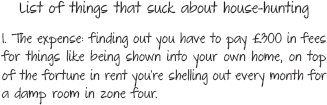

The only thing that made house-hunting vaguely bearable was to imagine I was researching locations for a new gritty TV show where people got murdered in the dingiest possible flats. CSI: Croydon. I put in my headphones as I trudged about and asked myself what Beyoncé would do, as I often pondered in moments of stress. Well, probably she’d charter her private helicopter and get airlifted to one of her mansions, so that was no use. I repaired to a café in Kentish Town, trying to cheer myself up with tea and a Florentine. Then the bill came to £4.50 and I realised I might not be able to afford cafés at all after this. I’d have to be one of those people who knitted jumpers and always took their own sandwiches wrapped in tinfoil, just like at school. This wasn’t what I’d grown up for. It was depressing indeed to realise you were no further up the pecking order than you were at seven.

I was on my phone, scanning the property websites for anything under £700 that didn’t look likely to have fleas/mould/sleazy landlords. Could I live in Catford? Was that even in London? Would I be able to stomach a large flat share, given I currently worked from home? Alternatively, could I live and work in a studio flat where you couldn’t open the fridge without moving the bed? Could I possibly get my freelance work going again to the point where I’d actually make some money?

I began scrawling figures on a napkin, but it was too scary, so I ordered another Florentine instead and then worried about money and calories and being single again at thirty. Not even single. Divorced.

I was getting back into some very bad thoughts—you should ring Dan, beg him to take you back, you can’t afford this, you can’t manage alone—when my phone rang. Emma. ‘Are you busy?’

‘No. Just contemplating the ruins of my life.’

‘Oh dear, is it not going well?’

‘Put it this way, the only person with less luck than me at choosing where to live is Snow White. I’ve seen most of the seven dwarves today—Grumpy, Horny, Druggy …’

‘Remind me again why you had to move out. It was your house too, and he was the one who wanted—’

‘I couldn’t afford the mortgage on my own. And you know it’s better to be in London for work.’ Work that I didn’t have yet. I wasn’t going to think about that.

‘Well, check your emails. I just sent you something.’

‘OK, let me find my phone.’

A pause. ‘You’re on your phone now, Rach.’

‘Oh, right. What did you send?’

‘An amazing flat share. It’s in Hampstead, lovely garden and house, but, best of all, it’s free!’

‘What? How is that possible?’ I was thinking of Mike, the ‘city gent’.

‘There’s some house-sitting and pet-sitting involved.’

‘Pets?’ I said warily, thinking of the cat house—ironically, not in Catford.

‘A dog.’

‘Oh my God!’

‘I know. So call them now! When I get off the phone, I mean.’

Sometimes I wondered if my friends thought I was a complete idiot. ‘Thanks. You’re sure it’s not a sex trafficking thing though?’

‘You can never be totally sure.’

‘Oh.’

‘I’ve got the address just in case.’

‘Thanks.’

‘I can craft the orders of service for your funeral. I just got a new glue gun.’

‘I’m going now! Bye!’

I hung up and waited for the email to download.

A flip of excitement in my stomach—when you reached thirty, property websites gave you the same feeling that dating websites did in your twenties. Not that I’d ever dated. The house was beautiful—three storeys of red brick, set among trees, and there was even a turret! Oh my God. I read on. Underfloor heating, en suite room, massive kitchen with dishwasher—some of the places I’d looked at didn’t even have washing machines. What was the catch? As I’d learned from my property search, there was always a catch. Under price, it said ‘N/A’. Could there really be no charge? I looked at the number listed and on impulse dialled it. I was only ten minutes from Hampstead, after all.

It went to voicemail. A man’s voice, deep and clipped. Slightly posh. ‘This is Patrick Gillan. Please leave a message.’

Voicemails are my nemesis. Cynthia still talks about the time I rang her at work to tell her I’d seen cheap flights to America, and ended up singing ‘Hotel California’ down the line while her entire office listened on speakerphone.

‘Erm … hi. I saw your ad. I’d like somewhere to live. I don’t have much money at the moment—’ Oh no, I shouldn’t have said that. Like with jobs and dating, the only way to get a room you really needed was to pretend you didn’t need it at all. ‘Erm … I mean, I’m looking to relocate and I am most interested in your room. I should like to view it at the earliest convenience. Erm … I’m down the road right now. Call me. Oh … it’s Rachel.’

I hung up. Classic rubbish voicemail, I’d managed to sound mad, posh and needy all at once. I paid for my biscuit and went out into the drizzle. Approaching me was a shiny red bus, slick with rain and the word ‘Hampstead’ on the front.

I’ve heard people say that they sometimes have moments when they feel as if Fate is tapping them on the shoulder and saying, ‘This way, please,’ like one of those tour guides with the little flags being followed around by Chinese tourists in matching raincoats.

I’ve never had this happen. Even if I did, I’d get stuck on the Northern Line and Fate would have left for another appointment. But that day I thought, sod it, I’m getting divorced, I have nothing to do and the bus is right there. So I got on. And, ten minutes later, I found myself ringing the bell at the house of Patrick Gillan.

Chapter Three

As I stood on the doorstep of a house on a tree-lined street in Hampstead, a dog started barking inside. I smiled. There really was one. I caught sight of myself in the shiny door knocker and sighed. My hair was frizzy with rain and I wore a fraying mac, jeans and holey Converse. When I worked in an office, tights were the bane of my life, like having cling film applied to your most delicate areas, always wrinkling round your ankles or laddering if anyone breathed in a ten-mile radius. So since going freelance—this was how I was choosing to describe my current circumstances to myself—I mostly worked in jeans … OK, pyjamas. The door had panels of stained glass, and I saw someone approach, turned different colours by the light. I stuck on my best ‘not a crazy person’ smile. The man who opened the door was holding a phone in one hand, and with the other had a barking Westie by the collar. ‘Shut up, Max!’ He, the man, not the dog, wore jeans and a soft blue-grey jumper. He had greying curly hair and a cross expression. ‘What is it? I don’t plan to vote in the council elections. Not until you do something about the disgraceful state of your recycling policy.’

‘No— It’s— I saw your ad. The room. I was in the area and …’

He stared at me for a few moments while the dog tried to climb up me.

‘I’m not mad,’ I said quickly.

‘That’s good to know.’

‘I suppose a mad person might say that.’ I laughed nervously.

He looked me up and down. Sighed. ‘You better come in.’

Sometimes, when you walk into a place, you know you were meant to be there. It just smells right or something. Dan hated this method I had of choosing houses. What do you mean it didn’t feel right? It’s got outdoor decking and a dedicated parking space!

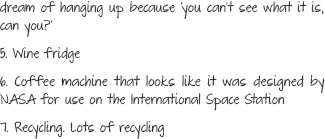

‘It’s amazing,’ I said. The inner doors all had stained-glass panels, filling the hallway with a kaleidoscope of colour. The floor was old-fashioned parquet, a little scuffed, and the place smelled of coffee and daffodils, of which there was a large handful crammed into a jam jar. I could tell instantly it was a middle-class home because:

The man still looked cross. ‘Come into the kitchen. I’m in the middle of something, so I wish you’d waited, but never mind.’

‘You’re sure?’

‘I said so, didn’t I? Do you want coffee?’

‘Oh, thank you, I don’t drink it.’ I may as well have said I didn’t believe in changing my socks.

‘You don’t?’

‘I don’t like the taste. I like the smell and I love coffee cake and those sweets you get in Roses. Isn’t that weird? I mean, hardly anyone likes those.’

He studied me. The phone in his hand chirped and he looked at it, frowned. ‘Tea, then?’

‘Yes, please.’

‘How do you take it?’

‘Milk, quite strong, but sort of milky if that makes sense.’

Once I sat down, the dog scampered across the kitchen and hurled himself onto my knee, where he crouched with his chin on my shoulder, panting. ‘Oof! Hello.’

‘He goes mad for new people. Sorry.’

‘It’s OK. I wish I had that effect on men.’ Oh, shut up, shut up, Rachel. Another side effect of working alone—you forget that there are supposed to be ‘inside head’ thoughts as well as ‘outside head’ sayings.

Patrick peered at the kettle. ‘So, Rachel—that’s you, I assume? What made you want the room?’

‘Honestly? I need somewhere to live at short notice. I also work from home at the moment, so I can’t really be in a big flat share.’ Or the sex slave of a rich city banker, come to think of it. All the sex-slaving would probably cut right into my freelancing time.

He was still frowning. ‘And where have you been living?’

‘Out in Surrey. I owned a place.’

‘Don’t you want to buy again, then?’

Things that suck about divorce, number fifteen: having to explain it to strangers. ‘My husband and I are splitting up. He’s keeping the house for now, so I have to move out.’ I cuddled the dog. ‘I’m in bit of a bind. But—’

‘You’re not mad.’

‘No.’

‘You’re getting divorced.’

‘Yes.’

He leaned against the counter and I saw he had no wedding ring on. ‘Join the club.’

‘Oh.’

‘Not much fun, is it?’

‘It sucks. In fact, I’m keeping a list. Things that suck about divorce.’

‘How many things are on it?’

‘Several hundred and counting.’

‘How about this one?’ The kettle had boiled, but he kept staring out the window. The phone beeped again, but he ignored it. ‘Having to find a lodger so they can dog-sit and look after the house, because you spend too much time at your job, and that’s why your wife left you in the first place, because with all the time she was on her own she had to find new hobbies, like, for example, having an affair with the next-door neighbour?’

I followed his gaze to the house just visible over the fence and nodded slowly. ‘I’ll put that one in after having to move out of the house you bought in the suburbs because your husband doesn’t want you there any more, but not being able to rent anywhere in London because you’re broke, so your only option is to move into massive house shares, or live with mad cat ladies or sex pests, or … answer weird ads that don’t list any rent.’ I paused. There were posh Waitrose biscuits on the table, so I crammed one into my mouth to shut myself up.

Patrick Gillan was watching me curiously. ‘Look, I have a demanding job, so I need someone here during the day, to be with the dog and take deliveries and maybe do some light au pairing, but I can’t afford a full-time housekeeper. I was just … thinking outside the box. I thought someone might do it in exchange for free rent. It was sort of a mad late-night idea, to be honest. I’m kind of at my wit’s end here.’

Free rent. FREE RENT. Suddenly, I was ripping up the calculations I’d done on the napkin and feeling a large weight lift from my chest. I wouldn’t be totally broke. I wouldn’t have to bring my own sandwiches when we went to Pizza Express and divide up the cost of each dough ball. He was still looking at me. ‘Why are you here, Rachel? I mean really?’

I was a little high on all this unexpected honesty, among the lies you get told when looking for a place to live, about south-facing lawns and nearness to transport and exactly how many cats there are in a given household. ‘Really? When I got married, we moved to Surrey and my husband, I mean, my ex—’ it was hard to say the word ‘—got me a job at the local council where he worked. Graphic design. But then he asked me to move out, and coincidentally, the next day, I was made redundant.’

He was still looking at me. ‘Kettle’s boiled,’ I pointed out. The biscuit was lodged in my dry mouth.

He shook himself and got a cup. ‘So you’re at home all day?’

‘Most days.’ I held my breath. This had been a problem with many of the rooms I’d looked at, landlords muttering about extra bills and so on. ‘I’m going to look for a job, obviously, but also try to build up my freelance work. I used to do a bit on the side.’

‘And you like dogs?’

‘Love them.’ I stroked Max’s head. ‘I was about to get one, but then—well. Everything happened.’

‘And would you mind sort of housekeeping a little, answering the phone, getting parcels, maybe sticking dinner on?’

‘Of course. I love cooking. And I don’t smoke and I’m … fairly tidy. You mean you literally wouldn’t charge me any rent?’ I looked at him suspiciously. ‘What’s the catch?’

He laughed, and instantly he looked ten years younger, happy, even a little wicked. ‘I was wondering the same about you. I suppose I should ask for references.’

‘Well. My previous landlord is my ex-husband, and my current boss is myself. Can you prove you’re not a mad killer?’

‘It’s hard to prove a negative.’

‘Hmm.’

‘Phone a friend, tell them where you are.’

‘But I would be dead by the time they found me.’

‘True, but at least you’d have a nice funeral.’

I was still thinking when there was a noise and the back door opened, and in trudged a small child in red wellies, clutching a big muddy bunch of daffodils. He was gorgeous—dark glossy curls, brown eyes. Maybe four or five. ‘I got some more, Dad.’

‘That’s good, mate. Give them here.’ Patrick looked at me over the child’s head. ‘I may as well explain—this is the catch.’

‘Cynth!’ I hissed.

‘Hello? Who is this? I’m not interested in PPI claims, thanks. Unlike some, I wasn’t stupid enough to buy it in the first place.’

‘It’s me. Rachel.’

‘Ohh! You’re still alive, then.’ I had emailed her to tell her about the possible flat share, figuring the more people who knew the better for retrieving my murdered corpse.

‘I took the room. God, the place is gorgeous.’ The room I was sitting in had more stained glass in the window, which looked out over Hampstead Heath. It was on the third floor, filled with light. I could put a drawing table in the window. There was an old wooden bed, a thick cream carpet and an en suite with a deep claw-foot bath. On the bedside table was a jar with more daffodils.

‘Alex,’ Patrick had said when he’d shown me up. ‘He won’t stop picking them.’

Ah yes. Alex.

‘So is it really OK? How on earth can he be offering it free?’

‘Well, there’s a kid.’

‘Ugh,’ she said. Cynthia felt about children the way most people felt about mould spores—some unfortunates had to live with them, but careful vigilance could prevent them from ever taking hold in the first place.

‘The dad, he’s getting divorced, so he has the kid.’

‘Where’s the mother?’

‘I’m not sure. Gone overseas to work for a while, I think.’

‘I see. He wants a free nanny.’

‘Well, Alex will be at school during the day. I think Patrick just wants someone to be here. Answer the phone, put the washing machine on.’ He’d described it as ‘Maybe I can help you, and you can help me’. I understood, I thought.

Cynthia was talking. ‘Make sure it’s not a de facto employee post, sweetie. You know how people are. Since you’re there could you just make the dinner, and do the shopping, and re-grout that bathroom … Working from home still means working.’

‘I know. But where else can I go? This is a million times nicer than anything I could afford.’

‘Well, OK. If you’re happy.’

I realised I’d talked myself into staying here, and before I knew it I was arranging to collect my things and move in that very night. Me, my ten thousand sketchbooks, my fifteen pairs of trainers and Bob the dog-substitute bear were going to make our home here.

Alex, apparently the world’s most biddable child, had presumably gone to bed when I came back with the van, and Patrick was in the kitchen with an iPad and glass of wine. There was a smell of stew in the air and a Le Creuset dish soaking in the sink. It felt weird. Like coming home, but to a home that wasn’t mine. He jumped when I let myself in, and I wondered if he’d forgotten he’d given me a key or, worse, forgotten me entirely. ‘Hello,’ I said.

‘Hi. You’ve got … things?’

‘Yes.’

‘I better help you.’

We hauled my meagre goods up the stairs. ‘What’s in here, rocks?’ Patrick asked, and I’d had to admit that yes, there were rocks in some of the boxes; I collected them for drawing practice. Dan had kept all the Ikea/Argos chipboard that furnished our marital home, so there wasn’t much. ‘Do you want a glass of wine?’ Patrick said, when the room was a mess of boxes and cheap Ikea blue bags.

I did, but I felt odd about sitting with him, and I was worried I’d been drinking too much as my marriage fell apart. ‘I’m OK, thanks. I’m very tired.’

‘I’ll leave you to it, then.’

I liked to think I was fairly spontaneous and fun. The kind of girl who’d jump on a train to Madrid with only the clothes on her back and not even book a return flight in advance. The kind of girl who bought train tickets at the station instead of getting them online for up to a third less. Who didn’t know what they were doing three weekends hence but was fairly sure it would involve a music festival and a twenty-four-hour drugathon with dubious men in goatees, and not a trip to Ikea for a new magazine rack.

I wasn’t spontaneous. Plus, I hated goatees. Things that suck about divorce, number twenty-two: nothing is where it should be. If you wanted to make your famous lemon risotto, the recipe books were still in the house, and you didn’t manage to get custody of the food processor. If you wanted to go hiking, your boots were in the car your husband/ex-husband was still driving to work every day. You wanted to wear a blue dress and realised it was at the dry cleaner’s, the ticket God knows where, and you weren’t making the thirty-mile trip for a frock from New Look anyway.

Nothing is where it should be. Not you. Not your heart. Not your life.

Finally, I’d unpacked nothing but my toothbrush and pyjamas, but I was in bed and was listening to the unfamiliar house around me. The trickle of old plumbing. The creak of the attic. I took out my phone—my screen saver was still a picture from two years ago, Dan and I doing a selfie at our wedding. He was planting a kiss on my cheek and I was smiling widely, as if I couldn’t even imagine a time when we wouldn’t be that happy. I thought about texting him to tell him I’d found somewhere, but I knew he wouldn’t care. That was another thing that sucked about divorce. You were hurting and lost and alone, and the only person you could think to tell about any of it was the one who no longer wanted to talk to you at all.

Chapter Four

When I woke up, it was the day after the first day of the rest of my life. No one ever talked about that. That’s the day when you have to live with your momentous decision, start redirecting post, unpacking boxes. My overwhelming wish was to lie in bed, sorrowfully dwelling on the terrible mess I’d made of my life. When you’re freelance, you see, you have those luxuries. But I didn’t get the chance, because I was woken at six by a tapping on the door. Mice? Ghosts? I cleared my throat. ‘Hello?’ Indistinct mumbling. A shy ghost? ‘You can come in!’

There was a fumbling and the door creaked open. In flew twenty pounds of overexcited dog. Max leapt up on the bed, where he rolled over with his feet in the air, indicating I could do as I wished with him. Sadly, it was only dogs who reacted this way to me in bed.

In the doorway stood Alex, holding yet more dripping daffodils. He wore one red welly, the other foot clad in a stripy sock, and a pretty on-trend onesie with Thomas the Tank Engine’s face on front. ‘Hello,’ I said.

‘’Lo.’ He stared at me out of his dark eyes.

‘Those are nice flowers.’

‘Flarrs for you,’ he muttered, darting in and crushing them onto my bedside table, where they left green smears.

‘For me? Thank you, Alex.’

‘Mummy likes flowers.’

Awk-ward. ‘I’m sure she does. And how is Max today?’

‘He’s not allowed on the bed.’

‘Is he not? He’s naughty, then, isn’t he?’

‘Yes. Can I come in the bed?’

‘OK. The more the merrier.’ Alex needed my help to get up, and I suggested he leave the remaining welly behind. He sat cross-legged, looking at me.

‘What’s your name?’

‘Rachel.’

I pitched around for four-year-old conversational topics. I liked kids but was still having conflicted feelings over whether I wanted them or not. Dan and I hadn’t even been able to manage a dog. I could feel the panic reach up in me from the pit—the one of ‘I’m broke and thirty and I’ll be alone forever’—so I focused on Alex. It’s hard to have existential horror when you’re with a four-year-old. They barely understand the concept of ‘tomorrow’ let alone ‘the rest of my miserable life’.

‘So who’s that on your onesie?’

‘’S Thomas.’

‘Oh yeah? Who’s your favourite person in Thomas?’

Alex and I were having a little chat about animated trains—I bluffed my way through, my sister has kids—when I heard footsteps coming up the stairs and Patrick burst in. He too wore a onesie in a fashionable nautical stripe, a thick grey jumper on top. ‘Alex! I told you to leave Rachel alone. She was sleeping.’

‘No, she wasn’t,’ said Alex, with impeccable logic. ‘Brought her flarrs.’

‘Yes, we’ve talked about this, mate. We have to leave some of the flowers in the garden or there won’t be any more. Come on, get down. You too, Max.’ Child and dog slid off the bed. Max waddled out, wagging his little tail and wheezing. Alex clung to his dad’s hand. Patrick took a look at me, in my alluring sleepwear—Bruce Springsteen T-shirt, fleece pyjamas with sheep on. ‘I’m sorry about them.’

‘It’s OK. It’s a nice way to wake up.’ Then I worried he’d think I meant him in his onesie, so I quickly said, ‘Max and Alex, I mean—I’ve always wanted a dog.’

‘That’s fortunate, because Max is very hard to shake off. I found him inside my coat the other day. I’ll try to keep them both out of here.’ He looked round at the mess of boxes and bags, paintbrushes rolling on the desk, reams of paper stacked about the place. ‘You’re an artist, are you? I didn’t quite catch what it was you did.’