Полная версия

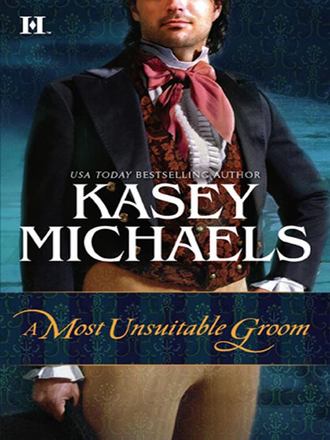

A Most Unsuitable Groom

KASEY

MICHAELS

A Most Unsuitable Groom

To Daniel Edward Seidick

Welcome to the world, Danny!

CONTENTS

BECKET HALL, ROMNEY MARSH

MORAVIANTOWN

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

EPILOGUE

BECKET HALL, ROMNEY MARSH

August 1813

AINSLEY BECKET sighed, then removed the spectacles he’d lately found necessary for reading and tossed both them and the letter on the desktop. “Well, I’ll say this for the boy. They didn’t execute him.”

“Execute him? Our Spencer? Our so mild, even-tempered Spencer committed a hanging offense? Imagine that. I know I can.” Courtland Becket reached for the letter that had taken several months to arrive at Becket Hall, most of them, judging from the condition of the single page, spent being walked to Romney Marsh stuck to the bottom of someone’s boot. “What did he do, get caught bedding the General’s wife?”

“If it were only that simple,” Ainsley said, getting to his feet to walk over to the large table where he kept a collection of maps he consulted almost daily, tracking the English wars with both Bonaparte and the Americans. “He’s in some benighted spot called Brownstown, or he was when that letter was written, nearly five months ago. From reports I’ve read in the London papers, if he’s still there he’s in the thick of considerable trouble.”

“Sweet Jesus,” Courtland swore quietly, scanning the single page, attempting to decipher Spencer’s crabbed handwriting and then read the words out loud, as their friend Jacko was also in the room. “‘Forgive my tardiness in replying to your letters, but I have been incarcerated for the past six weeks, courtesy of our fine General Proctor. Allow me to explain. Against all reason, Proctor left only our Indian allies to guard several dozen American wounded we’d been forced to leave behind at the River Raisin after what had been an easy victory for us. I was sent back a few days later to retrieve them, only to discover that the Indians had executed every one of them. Hacked the poor bastards to pieces, actually. You, I’m sure, know what this means. There will be no stopping the Americans once they learn what happened. And that’s the hell we face now. How do you fight an enemy that’s out to seek revenge for a massacre? They’ll fight to the last man, sure that to surrender means we’d turn them over to be summarily killed.’”

“The boy’s right,” Jacko said from his seat on the couch. “When it’s kill or be killed, a man can fight past the point of reason. Now tell me what our own brave soldier did that should have gotten him executed.”

“I’m getting to it now, I believe.” Courtland looked down at the letter once more, turning the page on its end in order to read the crossed lines. “‘I returned to our headquarters once I’d seen the bodies, walked straight into Proctor’s office and knocked him off his chair. I should have been hanged, I suppose, and it would have been worth it to see Proctor’s bloodied nose. But Chief Tecumseh, the head of all the Five Nations, agreed that this mistake could cost us heavily in the long run, and Proctor settled for stripping me of my rank and throwing me into a cell on starvation rations. Now I’m assistant liaison to Tecumseh—Proctor considers that a punishment—and I don’t like the way the Chief is being treated. Mostly, I don’t like that he’s smart enough to see through Proctor, which could end with a lot of English scalps hanging from lodge poles. In truth, I have more respect for these natives, who at least know why they’re fighting. And, yes, thinking fondly of my own scalp, I have been careful to be very friendly and helpful to Tecumseh. Rather him than Proctor.’”

“I don’t see a career in the Army for that boy, Cap’n,” Jacko said, winking at Ainsley, who had returned to sit behind his desk once more.

“Spencer hasn’t the temperament to suffer fools gladly, I agree. Truthfully, I’m surprised he only bloodied the man’s nose.”

“And, for all we know, Spence is still squarely in the thick of the fighting,” Courtland said, picking up his wineglass. “This Tecumseh might leave the English, leave Spencer, to their fate. Or, yes, turn on them, kill them. No matter what, I can’t believe nothing’s happened since Spencer wrote this letter. But what?”

“Exactly,” Ainsley said as he stood up and quickly quit the room.

“He’ll be walking the floors every night again until we hear from Spencer, searching the newspapers for casualties in the 51st Foot,” Courtland said, taking up Ainsley’s seat. “Damn my brother for wanting to be a hero.”

“A hero? Spencer? No, Court, not a hero. A man. Spencer wanted to be his own man, not just son to the Cap’n or brother to you and Chance and Rian. Time the rest of you figured that out. Ah, I feel so old, Court. How I long for the feel of a rolling deck beneath my feet, just one more time. Running with the wind, the Cap’n barking out orders and the promise of sweet booty at the end of a sweeter battle. I envy our young soldier that, at the least. I never planned to die in my bed. Yes, bucko, land or sea, I envy Spencer the battle.”

MORAVIANTOWN

October 1813

TO DIE, TO DIE very soon, seemed inevitable. To die for stupidity, for incompetence, was unforgivable. He should have done more than bloody the man’s nose.

Spencer Becket stood half-hidden behind a large tree, waiting for the Americans. He didn’t look much like a soldier in the King’s Army, having divested himself of his bright uniform jacket in favor of an inconspicuous buckskin jacket that had been a gift from Tecumseh himself—not because the man loved him, but so Spencer wouldn’t stand out like a sore thumb, making himself an easy target.

To his immediate left stood the skinny-shanked Clovis Meechum, who still liked to consider himself Spencer’s batman, even though Spencer had long since lost his rank and was now nothing more than another highly disposable infantryman like Clovis and his constant companion, the Irishman, Anguish Nulty. They still wore their uniform jackets, but the material was so filthy as to be nearly colorless.

Behind the three soldiers, melted into the trees, were Tecumseh and his warriors.

All of them were waiting for the Americans. Waiting to die.

“They’ll be coming up on us soon, Lieutenant?” Clovis asked quietly, fiddling with his powder horn. “We’ll turn ’em back?”

Spencer went down on his haunches to look straight into Clovis’s eyes, not bothering to remind him that he was a lieutenant no longer. Clovis made his own distinctions. “No, my friend, we won’t turn them back. But perhaps we’ll slow them down, give the civilians a chance to put some more distance between themselves and the main American force. Are you prepared to die today, Clovis?”

“No, sir, I don’t think so, at least not today. How about you, Anguish? You ready to cock up your toes for king and country?”

The Irishman scratched beneath his thatch of filthy, overlong hair. “And that I’m not, Clovis. It’s still longing to see this Becket Hall I am, what we’ve heard so much about. Sturdy stone walls, a warm fire at my feet, the Channel to m’back and nothing but nothing to do today and nothing more’n that to do again tomorrow.”

Spencer smiled, showing even white teeth in an otherwise deeply tanned and dirty face. He looked a rare hooligan, as Anguish had been so bold as to inform him, his thick black hair grown uncared for and much too long—releasing fat, waving curls, Clovis had added, that would be the envy of any female. “You forgot to mention the mug of ale at your right hand, Anguish.”

“That, too, sir,” Anguish agreed. “I’ll be sorry to miss it, that I will.”

“Then let’s be sure we don’t end our days here, all right?” Spencer stood up and looked across the river to the other bank once more. He was so tired. They’d abandoned Detroit, the soldiers and more than ten thousand men, women and children with all their belongings, all of them heading for the safety of the western part of Upper Canada before the worst of the winter arrived.

But they’d left their retreat too late, and the Americans were catching up to them. Spencer could already taste the bile of defeat at the back of his throat. Tecumseh’s idea was a good one—fighting with the swamp to their backs while the English forces pushed the Americans back to the river—but any hope of outflanking the Americans was just that, a hope.

“Here they come, Lieutenant. It’s been grand knowin’ you.”

Even as Clovis spoke, Spencer felt the earth begin to tremble beneath him, signaling the imminent arrival of the American cavalry. Above the rumble of hooves pounding against the earth, the battle cry “Remember the Raisin!” rolled through the air.

And then hell and all its fury came straight at them, and there was no more time to think.

Anguish went down, but Spencer couldn’t stop to examine the man’s wound. There wasn’t even time to curse Proctor, as he saw the man commandeer a wagon and drive off with his family, leaving the troops to raise the white flag.

With Clovis standing at his back, Spencer tried to load his rifle one last time, only to discover that he was out of powder. Spencer threw the weapon at the American running toward him, bayonet fixed to his own rifle, then ducked as Clovis’s knife found the man’s throat…but not before the bayonet had sunk deep in Spencer’s left shoulder.

“Sir!”

“I’m fine,” Spencer shouted, pushing Clovis away from him. “Our troops have surrendered, but there will be no surrender for the Indians. No surrender, no quarter. We have to get clear of here if we hope to save ourselves.”

“But the women, sir,” Clovis shouted back at him, pointing to the near-constant stream of English women and children, and Indian squaws and their children, all of them running blindly, terrified, racing deeper into the swamp.

“Hell’s bells, what a disaster!” Spencer pressed his hand to his shoulder, felt his blood hot and wet against his fingers. The pain hadn’t hit him yet, but he knew it would soon, unless he was dead before that could happen. “Where’s Tecumseh? Is he dead?”

“No, sir,” Clovis said, pointing. “There! Over there!”

Even now, the chief was ordering some of his warriors to their left, to fill a breach before the Americans could take advantage of it. And then he seemed to pause, take a deep breath and look to where Spencer stood. Slowly, he moved his arm away from his body, revealing a terrible wound in his chest.

“Christ, no!” Spencer shouted above the din, knowing that if Tecumseh fell, the Five Nations would all fall with him; the battle lost, the coalition broken. “We’ve got to get him out of here! Clovis! With me!”

But Clovis had slipped to his knees in the deepening mud and, when Spencer bent to pull him upright, he felt the sting of a bullet entering his thigh. Falling now, he never felt the fiercely swung rifle butt that connected heavily with the side of his skull….

“SIR? LIEUTENANT BECKET, sir? Sir?”

Spencer awoke all at once, his mind telling him to get up, get up, find Tecumseh and carry him away. But when he lifted his head the pain hit, the nausea, and he fell back down on the ground, defeated.

“Get him away…we can’t let them see…leave me…must get Tecumseh away…”

“He’s gone, sir,” Clovis said, pushing Spencer back as he once again tried to rise. “Dead and gone, sir, and has been for more’n week. They’re all gone, melting away into the trees like ghosts, even leaving some of their women behind to make their own way to wherever it is they’ve gone. It’s just us now. Us and poor Anguish and some others. Women and children who hid or were lost until the Americans took off again. They left us all for dead, but you’re not dying, thank God. You just lay still and I’ll fetch you some water. Water’s something we have plenty of. Cold and fresh.”

Spencer lay with his eyes closed, trying to assimilate all that Clovis had told him. Clovis was alive? Anguish was alive? Tecumseh…the great chief was dead? Damn, what a waste. He opened his eyes, wincing at the bright sunlight that filtered down through tall trees, their leaves already turning with the colder weather.

He moved his right hand along the ground, realized that he was lying on a blanket, realized when he tried to move his left arm that it was in a sling. He moved his legs, wincing as he tried to stretch out the right one. His head pounded, but he was alive and supposedly would recover.

But where was he? Still in the swamp? Yes, of course, still in the swamp. Where else would he be? A week? Clovis had a said week, hadn’t he?

“Here you go, sir,” Clovis said, holding out a silver flask as he raised Spencer’s head. “Don’t go smiling now, because it’s water I’m giving you. We used up the last of the good stuff on Anguish before we cut his arm off. Cried like a baby, he did, but that was the drink. He wouldn’t have made a sound, elsewise. Now hush, sir. It’s herself, come to look at you.”

“So he’s finally awake. Very good, Clovis.”

Spencer looked up toward the sun once more to see the outline of a woman standing over him, her long, wild hair the color of fire in the sunlight. A woman? But wasn’t that the scarlet coat of a soldier she was wearing? Nothing was making sense to him. Was she real? He didn’t think she was real. “An angel?”

“Not so you’d know it, sir,” Clovis whispered close to Spencer’s ear. “One of the women, sir. She’s been nursing your fever all the week long. Her and her Indian woman. They’re stuck here with us and she’s, well, sir, she’s the sort what takes charge, if you take my meaning. Other women are camped here with us, children, too, who hid out until the Americans left. We’ve been living off the dead, which is where I found the flask and blankets, but not much food. We’ve only three rifles betwixt us, and not much ammunition anyway. It’s a mess we’re in, Lieutenant, an unholy mess.”

Blinking, Spencer tried to make out the woman’s features, but now there seemed to be two of her, neither one of her standing still long enough for him to get a good look, damn her. “English?”

“You’re not a prisoner, if that’s the answer you’re hoping for,” the woman said, her accent pure, educated. “We’ll give him another day, Clovis, and then we have to be on the move north. Onatah says we’ll have snow within a fortnight, and we can’t just stay here and freeze as well as starve, not for one failed lieutenant. As it is, it will take us at least that fortnight to get to civilization. We’ll make a litter, and we’ll simply have to take turns dragging him.”

Then she was gone, and Spencer squeezed his eyes closed as the sun hit him full in the face. “You’re right, Clovis. Not an angel,” he said weakly, and then passed out once more.

CHAPTER ONE

Becket Hall

June 1814

“CAN YOU SMELL IT, Spencer? There’s a considerable storm churning somewhere out there. I imagine Courtland will have noticed, and won’t bring the Respite back from Hastings until it passes. That’s unfortunate. I was hoping to hear any war news he and Jack may have picked up while visiting my banker.” Ainsley Becket turned away from the open window overlooking the increasingly angry Channel to look at his son. “How’s the shoulder? Does it still pain you when a storm’s on its way?”

Spencer shook his head and returned to his glass of canary. Well, Ainsley had slipped that question in neatly, hadn’t he? “No, sir. If it did, I wouldn’t tell you. Because then you’d tell Odette and she’d be after me again with her damn feathers and potions. I’m fine, Papa. Truly.”

“And bored,” Ainsley said, seating himself behind his desk. “You won’t be leaving us again, will you, now that you’re recovered? Or should I refrain from mentioning that Jacko has compared you to a lion incessantly pacing in its cage? All that seems missing is the growl, but I doubt that will be the case for long.”

Spencer avoided Ainsley’s intense eyes, pretended to ignore the inquisitive tilt of the man’s head. He knew he was being weighed, judged. Even goaded. Quite the devious fellow, Ainsley Becket, for how smoothly he poked at a person. That was the trick with his papa—don’t trust the smile, don’t pay attention to the mild tone. Watch the eyes.

“No, I’m not leaving, Papa. I’ve had enough of Canada for one thing and now that Bonaparte has abdicated there’s nowhere else to go, no one else left to fight. I’ll just sit here and rust like everyone else, I suppose.”

“And the headaches?”

“Sweet Christ!” Spencer leaped to his feet and began to pace. So much for trying to keep himself in check. He remembered Jacko’s comparison and quickly stopped pacing, ordered his temper back under control. “I told you, I’m fine. Fully recovered, I promise.”

Ainsley kept pushing. “So you remember now? How you got to Montreal, how you were loaded on a boat and then onto the ship that brought you back to us? You remember more than being in the battle and then being at sea? You remember more than either Clovis or Anguish has told you?”

Spencer stabbed his fingers into his hair and squeezed at the top of his skull with his fingertips until he felt pain. “No, damn it, I haven’t. Odette says the good loas kindly took away my memory of those weeks, so that I don’t recall the pain. Loa protecting me or not, I got a whacking great bang on the head, that’s all. And I’m damned tired of being treated like an invalid.”

“And you’re bored,” Ainsley repeated, palming a brass paperweight as he continued to look at Spencer, the man who had once been a defiant orphaned boy of hot Spanish blood, wandering the streets of Port-au-Prince, barefoot and close to starving, yet ready to spit in the eye of anyone who looked at him crookedly. Ainsley had been forced to stuff him in a sack to keep the boy from biting him as he took him to the island and handed him over to Odette and Isabella’s tender mercies, the seventh of the orphans Ainsley had felt it necessary to take on to ease his increasingly uneasy conscience over the life he’d chosen. He’d named the boy Spencer, in memory of the sailor they’d lost overboard on their most recent run.

Within months of his joining them, they’d fled the island, Spencer still mostly wild, a wildness that had never really left him. What a long way they’d come. How little he still knew about his adopted son. The timing had been wrong. He’d brought Spencer into his world only months before he had wished himself out of it, and Spencer had been left mostly to his own devices for the past sixteen years.

“Spencer? You can say it. I do understand.”

“Then, yes, damn it, I’m bored! How do you bear it, living here, day after day after day, year after year after year? At least when the Black Ghost rode out, there was something to break the monotony. I’d almost welcome the Red Men Gang back to threaten us, just for the excuse to ride out, bang a few heads together.”

“There will be no more smuggling from these shores, Spencer, and therefore no need for the Black Ghost to ride out to protect our people. With Napoléon contained, the government is able to use its ships to set up a blockade all along the coast. Smuggling has become much too dangerous an enterprise. And I won’t commit the Respite again. It’s too risky for us.”

Spencer knew they were getting into dangerous territory now, and spoke carefully. “Not everyone in this part of the Marsh is willing to give up the life.”

“I’m aware of that. But we took more than a few chances these past few years, and I don’t believe in pushing our luck, so those who persist in making runs will have to do so without the protection of the Black Ghost.”

Spencer kept his gaze steady on his father. “A few of the younger men are restless, confined here the way they are. They want their turn outrunning the Waterguard. They want their own adventure.”

Ainsley steepled his long-fingered hands beneath his chin as he looked at his son. “You had yourself an adventure, Spencer. Killed your share of men, watched friends die. Do you really long for another such adventure?”

“You coming, Spence?”

Spencer turned his head to see that his brother Rian had poked his head inside the room. “Oh, right. I forgot the time,” he said gratefully, getting to his feet, careful to look Ainsley full in the eyes as he added, “If you’ll excuse me? A few of us are meeting at The Last Voyage. Would you care to join us?”

Ainsley smiled, shook his head in the negative, just as Spencer had known he would—or he wouldn’t have invited him. Not this evening. “No, thank you, I think not. And watch for the storm. You wouldn’t want to get stranded in the village for the night.”

“Because to walk home along the beach in the rain might serve to melt me.”

“Probably not, but neither of us really needs to have Odette ringing a peal over our heads about her poor injured bird, now do we?”

Spencer grinned. “It’s gratifying to know I’m not the only one afraid of Odette’s mighty wrath. I promise you again, I’m fine, completely healed,” Spencer said, sighing. “Good night, Papa. I’ll see you tomorrow. And the day after that, and the day after that…”

Spencer motioned for Rian to precede him into the hallway, and then the two brothers sought out woolen cloaks and made for the front door, hoping to avoid Jacko and anyone else who might ask where they were going. “You saved me there, you know. Papa was being his usual self, asking questions for which I have no answers.”

“You can thank me later. They’re probably all waiting for us now,” Rian told him, donning his cloak with a flourish that seemed to come naturally to the almost poetically handsome young Irishman, with his riot of black curls and clear green eyes, the almost feminine, soft curve of his cheek. Less than two years Spencer’s junior, he seemed so very much younger…possibly only because he was so damned inconveniently pretty. He needed a few scars; that’s what Rian needed, if he was ever going to convince anyone he was a man, even at the ripe old age of twenty-five.

“Good. If we can all agree tonight, the Black Ghost will soon be riding again,” Spencer said, stepping onto the wide stone landing, pausing only to look out over the endless flat land that was Romney Marsh. On a clear day a man could see for miles, see distant church spires taller than any tree, as the few trees that grew here could only rise so high before being bent over by the ever constant wind from the Channel.

This place was so different from the North American continent with all its tall trees, rolling hills, rushing cold, clean waters and bluer-than-blue skies. Romney Marsh was stark, not green.

Spencer had lied to Ainsley. He did miss America. It was an old land and yet also new; young and raw and vibrant. When Tecumseh had spoken of his land, he had made Spencer see it through his eyes. An all-glorious land of bounty and promise. And freedom. Maybe he would go back some day. Not to fight, but to explore, to find his place. Because much as he’d tried, as much as he’d attempted to conquer his discontent, his place wasn’t here at Becket Hall. That Ainsley knew this concerned Spencer, but he knew his father would not stop him when it came time to leave.

Rian hefted the lantern they’d need to guide them along the path to Becket Village. “Spence? They’re all waiting on us. You looking or moving?”