Полная версия

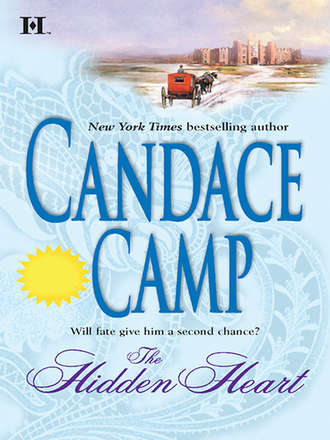

The Hidden Heart

The Duke of Cleybourne let out a low curse. “You don’t look like any governess I have ever seen.”

Jessica’s hands flew instinctively to her hair. Her thick, curly red hair had a mind of its own, and no matter how much she tried to subdue it into the sort of tight bun that was suitable for a governess, it often managed to work its way out. Now, she realized, after the long ride in the carriage a good bit of it had come loose and straggled around her face, flame-red and curling wildly. Embarrassed, she pulled off her bonnet and tried to smooth back her hair, searching for a hairpin to secure it, and the result was that even more of it tumbled down around her shoulders.

Cleybourne’s eyes went involuntarily to the bright fall of hair, glinting warmly in the light of the lamp, and something tightened in his abdomen. She had hair that made a man want to sink his hands into it, not the sort of thought he usually had about a governess—indeed, not the sort of thought that Richard allowed himself about any woman.

“Readers who enjoy historical regencies by Christina Dodd and Amanda Quick will find this book utterly irresistible.”

—Booklist on So Wild a Heart

The Hidden Heart

Candace Camp

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Prologue

The Duke of Cleybourne was going home to die.

He had decided it the night before, as he was standing in his study, gazing up at the portrait of Caroline that Devin had painted for him as a wedding present. Richard had looked at the picture, and at the smaller, less satisfactory one of their daughter, and he had thought about the fact that it was December, and the anniversary of their deaths would be coming up soon.

Their carriage had overturned and skidded over the slick, icy road and grass into the pond, breaking through the skin of ice on top of the water. It had been only a few days before Christmas when it happened.

He could still smell the heavy scent of fir boughs that decorated the house for the holiday. It had hung in his nostrils all through his illness and convalescence, like the cloying odor of death, long after the boughs had been taken down and burned.

It had been four years since it happened. Most people, he knew, thought he should have gotten over the tragedy by now. One mourned for a reasonable period of time, then gathered oneself together and went on. But he had not been able to. Frankly, he had not had the desire to.

He had left his country estate, taking up residence in the ducal town house in London, and he had not returned to Castle Cleybourne in all that time.

But last night, as he looked at the portrait, he thought of how tired he was of plowing through one day after another, and it had come to him, almost like a golden ray of hope, that he did not have to continue this way. There was no need to walk through the days allotted him until God in his mercy saw fit to take him. The Cleybournes were a long-lived group, often lingering until well into their eighties and even nineties. And Richard had little faith in God’s mercy.

He did have faith in his own pistols and steady hand. He would be the bringer of his own surcease, and the dark angel of retribution, as well.

So he rang for his butler and told him to pack for the trip. They would be returning to the castle, he said, and felt faintly guilty when the old man beamed at him. The servants, who worried about him, were pleased, thinking he’d thrown off his mantle of sorrow at last, and they packed both cheerfully and quickly.

And it was true, he told himself. He would end his sorrow. In the most fitting way and place: where his wife and child had died, and he had not saved them.

1

Lady Leona Vesey was beautiful when she cried. She was doing so now…copiously. Great tears pooled in her eyes and rolled down her cheeks as she took the gnarled hand of the old man lying in the bed. “Oh, Uncle, please don’t die,” she said in a piteous voice, her lips trembling slightly.

Jessica Maitland, who stood on the other side of General Streathern’s bed, next to the General’s great-niece Gabriela, regarded Lady Vesey with cool contempt. Her performance, she thought, was worthy of the best who trod the stage. Jessica had to admit that Leona looked lovely when she cried, a talent that Jessica suspected she had spent some years perfecting. Tears, she had heard, worked enormously well with men. Jessica herself hated tears, and when she could not keep them at bay, she gave in to them in the quiet and solitude of her own room.

Of course, Jessica, a supremely fair woman, had to admit that Lady Leona Vesey was beautiful when she was not crying, as well. She had been one of the reigning beauties of London for some years now—though she was considered far too scandalous to be admitted into the best houses—and if she was reaching the last few years of that reign, the golden glow of candlelight in the darkened room hid whatever ravages time and dissipation had worked upon her.

Lady Vesey was all rounded, succulent flesh, soft shoulders and bosom rising from the scooped neckline of her dress, more suitable for evening wear than for visiting the sickroom of an aging relative. Her skin was smooth and honey toned, complementing the gold of the ringlets piled atop her head and the tawny color of her large, rounded eyes. She reminded Jessica of a sleek, pampered cat—although she was apt to change into something more resembling a lioness when she was angered, as yesterday, when Leona had slapped a clumsy maid who had spilled a bit of tea upon Leona’s dress.

Jessica had itched to slap Leona herself at that moment, but, being only the governess of the General’s ward, she had kept her lips clamped firmly together. Though in normal times Jessica kept the General’s household running efficiently, Leona was not only above her in rank but, being the wife of General Streathern’s great-nephew, also had a claim of kinship. From the moment she and Lord Vesey had swept into the house, Leona had taken over, treating Jessica as if she were a servant.

“Oh, Uncle,” Leona said now, dabbing at her tears with a lacy handkerchief. “Please speak to me. It lays me low to see you this way.”

Jessica felt Gabriela stiffen beside her, and she knew what the girl was thinking—that the General was no real relation to Lady Vesey, being the great-uncle of her husband, and that Lady Vesey’s spirits were anything but lowered at seeing the General lying in his bed at death’s door.

In the six years that Jessica had been at the General’s house, the Veseys had visited but rarely, and usually those visits had been accompanied by a request for money. She had little doubt that it was money that had brought them flying to the old man’s bedside now. Less than a week earlier, General Streathern had received a letter telling him of the death of an old and dear friend. He had jumped to his feet with a loud cry. Then his hand had flown to his head, and he had crumpled onto the carpet. Servants had carried him to his bed, where he had lain ever since, inert and seemingly insensible to everything and everyone around him. Apoplexy, the doctor had termed it, with a sad shake of his head, and held out little hope of recovery, given the General’s advanced years. The Veseys, Jessica was sure, had dashed to his bedside because they hoped to be named in the General’s will.

Jessica had tried her best to put aside her antipathy to Lord and Lady Vesey. They were, after all, Gabriela’s only living relatives besides the General, and, as such, she knew with a cold queasiness, in all likelihood Lord Vesey would become Gabriela’s guardian if the General did indeed die, which seemed more likely with each passing day.

She told herself that some of her dislike of Lady Vesey stemmed from that woman’s voluptuous beauty. Jessica had grown up stick-thin, with a wild mop of carrot-colored hair, her eyes and mouth too big in her starkly thin face. As an adolescent, she had towered over all the other girls—and most of the boys, as well—gangly and awkward and feeling hopelessly unfeminine next to the soft, small, rounded females all about her. And even though her figure had eventually ripened into womanhood and her face had filled out and softened, and her hair had deepened into a rich, vibrant red, so that she had become a statuesque and striking-looking woman, Jessica still felt twinges of envy and awkwardness around women like Leona Vesey, who used their lush femininity as a form of weapon.

Also, she admitted that she had prejudged the woman because of letters from Viola Lamprey, the lone friend who had stuck by Jessica through all the scandal concerning Jessica’s father. Viola had married rather late but startlingly well, becoming Lady Eskew three years ago and living at the height of London society. She and Viola had continued to correspond all through the years after the scandal, and Viola loved to keep Jessica amused with her witty, entertaining tales of the scandals and excesses of the Ton.

Lord and Lady Vesey were often the topic of gossip. He, it was said, was much too fond of very young females, and she had been carrying on a very well-known “secret” affair with Devin Aincourt for over a decade. A few months ago Viola’s letters had been full of the stories circulating through London concerning Aincourt’s sudden marriage to an American heiress and the subsequent termination—by Aincourt, not Lady Vesey—of the long-standing affair. The ladies of London were gleeful. Leona Vesey had few friends among them, having often made it a point to demonstrate how easily she could take away any of their husbands or suitors.

Jessica knew she should not have judged Lady Vesey on the basis of gossip. After all, she had certainly been at the center of a great deal of unfair gossip herself ten years earlier. When the Veseys had arrived here, she had made an effort to look at Lady Vesey afresh, untainted by preconceptions and prejudices. But it was soon clear to her that gossip had, if anything, not painted the lady black enough. Leona Vesey was selfish, vain and mean-tempered. She was contemptuous of all those of lower station than she, and she was pleasant only to those whom she thought could help her, usually men. The Veseys had been here for only three days, and already Jessica could barely stand to be in the same room with either of them.

She felt Gabriela tense beside her, and she suspected that the girl was about to unleash her anger on Leona, so Jessica quickly linked her arm with Gabriela’s, casting her a warning look. She was worried for Gabriela’s future. If the General should die and she was given to Lord and Lady Vesey as their ward, her life would be hard enough without her already having earned the enmity of Lady Vesey.

“Oh, please, Uncle,” Leona said, her voice breaking as she bent over the still form of the old man, waxen in the dim light. “Please say some parting word to me.”

Suddenly the old man’s eyes flew open. Leona let out a small shriek and jumped back. The General stared at her with piercing hawk eyes.

“What the devil are you doing here?” he asked, his voice scratchy and fainter than his usual bark, but his annoyance clear.

“Why, Uncle,” Leona said, recovering some composure, though her voice was still a trifle breathless. “Vesey and I came because we heard you were ill. We wanted to be with you.”

The old man glared at her for a long moment. “Afraid you might lose your share of my estate is more like it. Ha! Well, I have news for you. I ain’t dying. And even if I was, I wouldn’t be leaving anything to you and that roué of a husband of yours.”

“Uncle…” Lord Vesey, standing behind and to the side of his wife, tried an indulgent laugh. “You will give everyone the wrong idea. Others are not aware of your little fondness for jokes….”

“I wasn’t talking to you,” the General pointed out sharply, sounding stronger with each passing moment. “Damme! Nobody invited you here. You’re a damned nuisance.”

“Oh, Gramps!” Gabriela burst out, unable to restrain herself any longer. “You’re all right! We thought you were dying.”

The General turned his head and saw Gabriela standing on the other side of the bed, Jessica behind her, and he smiled.

“Now, would I do a thing like that?” he asked, extending his hand to the girl.

Tears spilled out of Gabriela’s eyes, and she leaned forward to take her great-uncle’s hand. “I am so glad you are all right. We were horribly scared.”

“I’m sure you were, Gaby.” The old man squeezed her hand with only a remnant of his former strength. “But no need. I’m still breathing.”

He looked toward the foot of the bed, where his doctor and the village vicar stood, staring at him in astonishment. “No thanks to you, I’m sure,” General Streathern went on, talking to the doctor. “Go away. You look like a couple of damned crows standing there. I’m not dying.”

“General, you must not excite yourself,” the doctor said in a calming voice. “You have been unconscious for almost a week now.”

“No, I haven’t. Woke up last night. Just went back to sleep.”

“It must have been the sound of Lady Vesey’s voice that got through to you,” the vicar said, with an admiring smile in that woman’s direction.

“Humph!” the General responded. “Well, you were a fool when you were young, Babcock, so no use expecting you to be any better when you’re old. Hearing that baggage’s voice is more likely to send me over than bring me back.”

“What!” Leona exclaimed, setting her hands on her hips indignantly. “Well, I like that. We left London and drove all the way up to this godforsaken place just because we heard you were ill. And this is the thanks we get?”

“I didn’t ask you to come here,” the General said reasonably. “Nobody did. You came because you hoped there was money in it for you. It’s the only reason the two of you ever set foot in this house, and I told you last time not to return. You’re damned nervy, that’s all I can say, to come strutting back in here. You are a conniving bit o’ muslin, Leona, and I thank God you’re not my blood relative. I wish I could say the same about that piece of trash you’re married to.” He broke off his harangue long enough to shoot Lord Vesey a malevolent glare. “Now get out, both of you. I don’t want to see your faces again.”

“Perhaps we had best go back to our rooms,” Lord Vesey suggested to his wife, looking a shade paler than he had a few moments before.

“Your rooms? You’re staying here?” The General’s face reddened alarmingly.

“Why, yes, of course,” Leona replied. “Where else would we stay?”

“I told you you were not welcome in this house,” the General snapped, struggling weakly to sit up.

“Please, General, calm yourself,” the doctor said, hurrying around the bed to put his hands on the old man’s shoulders and push him back down flat on the bed. “You will bring on another apopolexy if you don’t watch out.”

“The devil take it!” General Streathern glared at the doctor, but he didn’t have the strength to defy him. “I want them out of my house, do you understand?”

“But, General,” the vicar protested. “Lord Vesey is your nephew. And Lady Vesey—”

He broke off abruptly as the General fixed him with a glare.

“This is my house,” General Streathern said coldly, “and I am in charge of who does and does not stay here. Don’t tell me who I can have in my house, Babcock.”

“No, of course not, General,” the vicar said, forcing a smile. “I did not mean to be presumptuous. It is just—they traveled so far, and where are they to stay?”

“Let ’em stay with you, if you like them so much.”

Reverend Babcock chuckled indulgently, a sound that seemed to irritate the irascible old man even more.

“There’s an inn in Lapham,” he said, naming the local village. “Let them stay there if they’re so bloody-minded they have to remain. But I refuse to let them torture me with their whinings and cryings and making my servants unhappy. Nothing worse than having the maids weeping all over the place because he’s backing them into corners and taking liberties or she’s screeching at them like a harpy and slapping them. If a man cannot have peace when he’s been at death’s door for a week, then I don’t know what the world’s coming to.”

“Of course you can have peace,” the doctor told him soothingly, sending an expressive look in the direction of Lord and Lady Vesey. “My lord…”

“Yes, yes, of course.” Lord Vesey gave a smile that looked more like the death rictus of a corpse. “Anything to make the General feel better. Lady Vesey and I will take our leave right away.”

He took his wife’s hand, and they started from the room. The General turned his head toward Jessica. “Jessica. Make sure they leave.”

“Of course, General,” Jessica told him with a smile. “I shall be happy to.” She faced the others remaining in the room. “Gabriela, Vicar, why don’t we let the General talk to the doctor now?”

The clergyman was obviously eager to leave the sickroom—whether because he feared the General or was hoping to find Lady Vesey, Jessica wasn’t sure. Gabriela fairly skipped down the hall, keeping up a constant stream of chatter directed at Jessica.

“Oh, Miss Jessie, isn’t it wonderful? I was so sure that Gramps was going to die! I should have known that he was tougher than some old apoplexy.”

Jessica smiled at the young girl. At fourteen, Gabriela was already promising to turn into a beauty. Though her figure was still as slender and flat as a boy’s, there was a litheness to her walk that promised a future grace, and her skin was fresh and creamy, her face lively and well put together, with large, dancing gray eyes and a tip-tilted nose.

Jessica was glad to see her charge so happy, but deep inside she could not keep from having a few doubts herself. The General might have awakened and seemed his old self. He might regain his full strength. But Jessica had noticed, even if Gabriela had not, that the left side of the old man’s face had not moved much when he talked, and his left hand had not curled around Gabriela’s in response to her taking it in hers. He had been unconscious for some time, and if nothing else, he was bound to be far weaker than normal. He was an old man, and the old were always susceptible to fevers and coughs, especially when they were weakened by illness.

She worried about the General, not only because she was fond of the him, but also because his sudden illness had brought home to her how vulnerable Gabriela was. Underage, orphaned, she might very well be left to the mercies of such people as the Veseys. Jessica had taken care of Gabriela, been her companion, teacher and confidante since the girl was eight, and she loved her as if she were her own sister. But in the eyes of the world, hers was only a paid position, and if the General died, whoever became Gabriela’s guardian could terminate Jessica’s employment, and she would have no recourse. She had worried over the matter ever since the General fell ill.

Gabriela went upstairs with the promise that she would work on the studies she had neglected during her great-uncle’s illness, and Jessica turned into the kitchen to find the butler, Pierson, and inform him of the General’s miraculous recovery and his subsequent banishment of the Veseys. Nothing, she knew, could make the servants happier than those two events.

As she expected, the butler beamed when she told him what had taken place in the General’s bedchamber upstairs and assured her that he would assign two maids, not one, to packing up the Veseys’ baggage and would personally escort them to their carriage.

Jessica returned to the nursery upstairs, where her and Gabriela’s bedrooms lay, separated by the schoolroom. As she passed the Veseys’ room, she heard the sound of something breaking, followed by Leona’s high-pitched, angry voice and Lord Vesey’s lower-pitched but no less furious one. Jessica smiled to herself and continued on her way.

The doctor left, and not long after that, Lord and Lady Vesey also quit the house. Humphrey, the General’s valet, stayed by the old man’s side throughout the rest of the day and that night, relieved—after great resistance—for a few hours at a stretch when Jessica or the butler or the housekeeper took over his role of nursemaid.

The General slept much of that time, waking up now and then to complain of feeling hungry and devouring first a bowl of consommé, then gruel and, finally, demanding soup with some substance to it. With each irascible command or gripe, the spirits of the household lightened. The General was becoming more and more normal.

Jessica visited the old man with her charge every morning and evening, and she could see visible improvement in him each time. She was very happy, not only for Gabriela’s sake, but because she was fond of the General. When the scandal broke and her father was cashiered out of the army, most of their acquaintances and friends, even the man she had thought loved her, had turned away from her, but General Streathern had not. He had come to pay his condolences after her father’s death, a courtesy few other of his military friends had seen fit to exercise.

Her father’s death had left Jessica penniless. She had refused to seek the help of her father’s family, who had scorned him after the scandal. For a time she had stayed with her dead mother’s brother, but it had been an untenable situation. He had five daughters of his own, all coming up to marriageable age and making their debuts. The last thing they needed was another young female about the place, and Jessica, whose father had raised her to be strong-minded and independent, was accustomed to running a household, not living meekly in one. She and her aunt did not get along, and she had soon seen that she could not live with them, either. There had followed a series of positions as governess or companion, but she was generally considered too young or too attractive or too tainted by scandal to be hired, and when she was, she often found herself leaving because of the unwelcome advances of a male of the house.

It had struck Jessica as grimly ironic that she, who had struggled through her younger years as a gawky, clumsy ugly duckling of a girl, had now somehow become the unwelcome object of male lust. She knew that the development of her late-blooming figure had had something to do with it, but she had difficulty recognizing that her despised riot of flame-colored hair was a lure to men, or that her features, once too large for her face, had matured into striking beauty. So, rather cynically, she laid the bulk of the blame for her attraction for men on the fact that they were drawn to her because she was no longer under her father’s protection. They wanted her, in short, she decided, because they thought she was an easy target now, a woman who was at their mercy because she had to work for a living.

Dismayed and embittered, she had stopped applying for positions as a governess and had managed to scrape out a living taking in fancy sewing. She had a good eye and hand for needlework, and when she swallowed her pride and went humbly asking for work, a number of women of wealth and position had paid for beautiful embroidery. Still it was a difficult and minimal living, and there were times when she despaired. Winters were the worst, for it cost more to live, as she had to heat her small room. She tried to save on coal, but she could not do the fine threadwork with fingers that were freezing. One winter, about six years earlier, the amount of sewing that she had been given had fallen off, and then she fell ill and had to turn away work for a week. She found herself suddenly on the brink of disaster, and she was forced to consider going back to live with her uncle or even asking her father’s stiff-necked family for help.