Полная версия

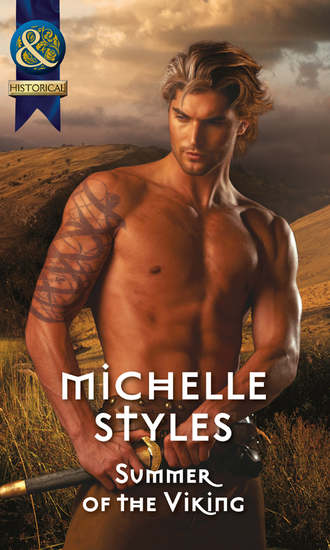

Summer Of The Viking

‘I would defend you to my dying breath,’ he said.

‘Our people are enemies, Valdar. Enemies,’ she replied.

‘Are we enemies, Alwynn?’

‘We are certainly not friends.’

‘We were lovers.’

‘That is in the past.’

He went over to her, magnificent in his nakedness.

‘It will never be over between us as long as I have breath in my body.’

AUTHOR NOTE

Having looked at the Lindisfarne raid from a Viking perspective, I became interested in looking at what it might have been like from a Northumbrian one. In particular I wanted to tell the story of how a woman might react if she accidentally fell in love with a Viking.

While I was mulling over the possibilities my fellow historical author and friend Annie Burrows asked, ‘So, when are you going to tell Valdar’s story?’ Valdar was the man left at the altar when Kara’s husband, Ash Hringson, appeared after a seven-year absence in Return of the Viking Warrior. And I knew I had found my hero.

As I did my research I was intrigued to learn about St Cuthbert’s storm, which happened in 794. When raiders appeared for a second time, apparently they were suddenly swamped by a terrific storm. The King of Northumbria managed to kill the leader and the rest either drowned or were killed. After that the raids in Northumbria decreased significantly for a time, but remained a concern.

I do hope you enjoy reading Valdar’s and Alwynn’s story as much I did writing it.

I love getting comments from readers and can be reached at michelle@michellestyles.co.uk, through my publisher, on Facebook or on Twitter @MichelleLStyles

Summer of the Viking

Michelle Styles

Born and raised near San Francisco, California, MICHELLE STYLES currently lives near Hadrian’s Wall with her husband, a menagerie of pets and occasionally one of her three university-aged children. An avid reader, she became hooked on historical romance after discovering Georgette Heyer, Anya Seton and Victoria Holt.

Her website is michellestyles.co.uk and she’s on Twitter and Facebook.

For Linda Fildew,

because she always likes a good Viking story

Contents

Cover

Excerpt

AUTHOR NOTE

Title Page

About the Author

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Extract

Copyright

Chapter One

June 795—off the coast of Northumbria

The possibility of returning alive to Raumerike and Sand hung by the slenderest of threads. After weighing the odds, Valdar Nerison figured he was never going to see his nephews again, never going to sit under the rafters of his hall and never going to breathe the sweet air of home again. He knew that in his heart. He’d known it ever since the mutineers had struck five nights ago, killing his friends, including the leader of the felag.

Girmir, the leader of the mutiny, would strike before the ship reached Raumerike’s shore, most likely when the familiar outlines of the houses came into view. But right now they needed Valdar alive to navigate with the sunstone. Girmir’s mistake was that he assumed Valdar believed his bland reassurance about how valuable he was.

The only question in Valdar’s mind was the timing of the escape. When should he make his move? They watched him like ravens and had taken all his weapons.

Valdar bent double over his oar as the rain and the waves lashed him, trying to reason out the best moment. Rejecting first one plan then another as unworkable. With each passing day, it became clear that the men believed Girmir when he proclaimed that they would acquire gold and slaves beyond their wildest imaginings if they followed him.

As the gale intensified, Girmir started muttering about making a sacrifice to the storm god, Ran. A human sacrifice. ‘Better one should die than the entire boat,’ he announced. It chilled Valdar’s blood.

Valdar glanced to his left as a flash of lightning lit up the sky. In the distance he spied the shadowy shape of land. For the first time since the mutiny, a glimmer of hope filled him. One long-ago summer, he and his brother had learnt to swim. Even after all this time, he reckoned that he just about remembered the strokes. One chance to get it right.

‘The storm increases. Ran and Thor are both in a terrible temper,’ he shouted as another blast from Thor’s anvil reverberated through the sky. ‘If you are serious about a sacrifice, do it before the entire boat is swamped.’

‘Do you wish to challenge for the leadership?’ Girmir came forward and put a knife against Valdar’s neck. ‘You know what happened to Horik the Younger when we fought. And to Sirgurd.’

‘Your boat now, Girmir, but I’m entitled to an opinion.’ Valdar ceased rowing and stared at the usurper, who had attacked at night, killing Horik before he could reach for his sword. Then forced Sirgurd to fight when he was clearly ravaged by fever. ‘The storm may be difficult to ride. We should put to shore.’

‘The only way which will quiet the gods in this weather is a life. I’ve seen it before.’ Girmir nodded towards where the youngest member cowered beside his oar. ‘A noble thing to give one’s life for one’s friends. Someone should volunteer.’

The boat became silent as all the men paused in their rowing.

‘Me?’ Valdar enquired as the wind howled about them.

Girmir adopted a pitying expression. ‘We have need of you and your navigational skill, Valdar Lack-Sword. I gave my word. You will see Raumerike again.’

‘If it is such a noble thing, then we should draw lots,’ Valdar said, ignoring the jibe and laying the trap. Girmir would murder him as soon as the cliffs of Raumerike were spotted. Earlier if it suited him. Once an oath-breaker, always one. ‘Let the gods decide...unless you fear their judgement.’

Even Girmir’s loyal followers muttered their agreement. Girmir’s beady eyes darted right and then left, seeking friends and finding none.

‘Which will it be?’ Valdar pressed, as another lightning bolt ripped through the sky, highlighting the men’s drenched and pinched faces. ‘Which is Ran most likely to be satisfied with—your choice or his?’

The other man blanched slightly, belatedly realising he had tumbled into a trap. ‘I will abide by the gods’ decision.’

‘You will not mind if I hold the counters,’ one of the men said.

Girmir bowed his head. ‘Go ahead and Valdar Lack-Sword can prepare them. I wouldn’t want to be accused of cheating the gods.’

Valdar retrieved a set of tafl counters from his trunk, placed them in a sealed pouch, carefully showing everyone the one black stone, and gave the pouch to the man who’d asked for it.

After days of inaction and humiliation, it felt good to be doing something. One way or another, he would regain his self-respect before he died. For too long he’d lived with this hungry animal gnawing at his belly, telling him that he should have heeded Horik’s request and sat up with him that night.

He should have woken before Horik the Younger was murdered, before his own sword was taken from him. He should have gone against his years of training, followed his instinct and become involved before things spiralled out of control.

If this boat went down, other than the boy, there was not a man he’d try to save. They had Horik’s blood on their hands. They had all stabbed Horik’s body under Girmir’s orders to prove their undying loyalty. When Valdar had made only a token stab at the lifeless body, he had seen Girmir’s face contort and had known that his fate was sealed.

‘Go first, Girmir, you are the leader!’

Sweat beaded on the man’s forehead. ‘Ha! A white counter!’

One by one each of the felag took their counter. The youngest blanched as he saw he’d drawn a counter darker than the others. Valdar put his hand over the boy’s. ‘Open your hand and turn the stone over. You only think it is black.’

The boy did as Valdar bade. ‘The stone gleams white on this side. But I thought...’

‘Funny how that works.’

Valdar regarded the cliffs on the horizon as he weighed the pouch in his hand. He could do it. He knew how to swim. His body tensed with nervous anticipation. Better to die fighting than to be slaughtered like a sheep. Cheating the gods to palm the black stone from the boy? Maybe, but they had deserted him five nights ago.

‘The gods want my hide today.’ He held the jet-black stone aloft.

He waited as the other warriors glanced between each other and muttered. But the relieved look on the boy’s face was worth it.

Girmir shrugged. ‘The gods have decided. Your arms will be bound, Nerison, but Ran prefers his victim alive so I shall not slit your throat. I’ll let him do it.’

Valdar closed his eyes. He should have expected Girmir’s sadistic twist of binding his arms. His legs would have to be strong enough if he couldn’t free his wrists. He would be able to make it to the shore. ‘As you wish. But know one day there will be a reckoning. The gods will punish those who break their oaths.’

Girmir clasped his forearm after he gave Valdar his share of the takings thus far. ‘Your sacrifice will appease the gods. You may have your sword returned. You behaved with honour. May you die with honour.’

After buckling his sword to his waist, Valdar tossed the sunstone to the young boy. ‘Have charge of the navigation now. Use it well. Like I showed you.’

Girmir’s eyes bulged. ‘He can navigate?’

‘You wouldn’t want to lose another navigator, Girmir. How else would you make it back home?’

The boy’s ears coloured pink. ‘I’ve always admired you, Valdar. I know what you did for me.’

‘Then tie my ropes.’ Valdar grasped the boy’s hand. ‘Will you do that for me?’

The boy’s eyes grew wide. ‘Aye, I will.’

‘Good lad.’

‘When you return home, the sunstone will be waiting for you. Just ask for Eirik, son of Thoren, and they will find my cottage. My mother moves about a great deal,’ the boy whispered. ‘The Norns are not finished with you. I know this in my heart.’

‘I’m to be sacrificed.’ Valdar moved his wrists, creating a gap. ‘How can they not be ready to snip my thread of life?’

‘My mother always says this.’ The boy tied the ropes with a bit of slack. ‘You have to believe that the Norns decide when your thread is snipped, not you.’

‘Get on with it!’ Girmir shouted above the rumble of thunder. ‘Thor’s anger increases.’

Valdar nodded and balanced on the snarling bear post on the prow of the ship. The wind whipped fiercely about him. He tried to think of all that he had done and had left undone, but all he could think about was the low white cliffs he spied on the horizon. There was a slim possibility that he could make it. That the gods wanted him to live. That with his sword arm and the gold in his pouch, he could get justice for the dead.

He listened to the ritual words, then jumped. The water hit him, stinging with its bone-chilling cold. He went down and down with blackness swirling about until his lungs wanted to burst. Then he began to kick his legs. Up and up until his head breached the waves. He wriggled his arms until the knot gave way and they were freed.

The ship had already disappeared from view and all about him was dark grey. Valdar spun around until he spied what appeared to be a white sandy beach and started towards it. With each kick of his legs, more about the technique of swimming came back to him.

Some day there would be a reckoning. And Girmir would pay dearly, he silently promised. It was as good a reason to live as any.

* * *

Alwynn shielded her eyes against the bright sun which now sparkled on the calm blue sea and surveyed the coastline. Last night’s storm had brought in more than its fair share of seaweed, wood and sea coal. But there was little sign of bodies or wrecked ships as there had been at this time last year after St Cuthbert’s storm had saved them all from invasion.

This time, there was plenty to be had for the scavenging instead of bodies being strewn everywhere.

She gave a small shake of her head. She hated to think what her mother would have said about her daughter, a woman with royal Idling blood in her veins, actually scavenging bits of flotsam and jetsam up from a beach. In her mother’s world, high-born women stitched fine tapestries for the home or church and ran well-ordered estates. They most definitely did not dirty their hands with sea coal.

Her mother had never had to survive after her husband died suddenly, leaving a mass of unpaid debts. But Alwynn had—selling off all that she could while still managing to retain the hall and some of the estate.

‘I do what I have to do! How can I ask others if I refuse to do it myself?’ Alwynn bent down, defiantly picked up a lump of sea coal and held it aloft before placing it in a basket.

If the harvest proved profitable and everyone paid their rents on time, her trouble would be behind her and she could leave the sea coal to others. In due course Merri might even be able to have a decent dowry and the chance of finding a worthy husband. For herself, she simply wanted to be left in peace to cultivate her garden. She wanted the freedom to choose whom she would marry or even whether she would marry. Or if she should enter a convent or not. But for now, she needed every lump.

‘You see, I was right!’ Merewynn ran up and plopped a double handful of sea coal into the basket. Her blonde curls escaped from the couvre-chef that Alwynn had insisted her stepdaughter wear. Merewynn would be ten in the autumn. It was time she started to act like a young woman, instead of a wild thing who roamed the moors. ‘Lots of pickings after a summer storm. We might even find treasure and then you wouldn’t have to worry so much about the render you owe the king. It is a wonder we never came down here before. Such fun!’

‘Mind you keep close, Merri. And no animals rescued. Our new hall is overcrowded as it is.’

Merewynn pulled a face. ‘If we look, I’m sure we can find a little space. A mouse wouldn’t take up much room. Or maybe a raven. I’ve always wanted a pet raven. And there is no Father Freodwald to complain about the mess now.’

Alwynn schooled her features. Their current priest had complained a great deal and it had been a relief when he departed for another longhouse. Someone else would have to provide the large amounts of ale, sweetmeats and blazing fires to warm his bones that the priest demanded as his due. It had been a shock because the old priest had been entirely different. ‘The bishop holds him in high esteem.’

‘But he dislikes ravens. St Oswald’s bird. Can you believe it? He said they nip fingers and make a mess everywhere.’

‘Just so we are clear.’ Alwynn put her hand on her hip and gave Merri a hard stare. ‘We are here to find things to put to practical use, not more animals for your menagerie. I’ll not have more land taken from us. You need to have a decent dowry when the time comes. On my wedding day, I promised to look after you as if you were my own.’

Merri gave a deep sigh. ‘I liked it better when you didn’t have to be practical, Stepmother. Sometimes it takes a little while before you realise you need something and then...’ She snapped her fingers. ‘A raven could be trained to send messages. If the Northmen attempt to attack, we could release it and it’d fly straight away to King Athelfred and he could pray to St Cuthbert to send another storm and...’

‘You are asking a lot of this unknown raven.’

‘Ravens are like that and I want to be prepared in case the Northmen come to murder us in our beds.’ Merri gave a mock shiver.

‘After last year’s storm, it will be a while before they try to attack again. They lost a number of ships and their leader. Remember what the king said.’

‘Or maybe we could find a falcon with a hurt wing,’ Merri continued on. ‘It could belong to an atheling who would fall instantly in love with you and we will all live happily ever after. You could even become queen.’

‘You listen to far too many tales, Merri. The king is my distant cousin. I wish him a long life.’

‘The atheling could come from another kingdom. One without a good king.’

‘Merri!’

‘Well...’ The girl gave an impudent smile. ‘It could happen.’

Alwynn glanced down at her woollen dress. With three patches and a stained lower skirt, it had definitely seen better days. And she wasn’t going to think about Edwin’s disreputable offer to become his mistress after the king confirmed him as the new overlord in this area. He was from the same sort of mould as her late husband—more interested in his advancement than the welfare of others. She shuddered to think that as a girl she’d begged her father to allow her to marry Theodbald. He’d seemed so kind and handsome with his little daughter cradled in his arms.

‘What do I have to offer anyone, let alone a king-in-waiting?’

‘You have dark hair and eyes like spring grass. And you are intelligent. You know lots about herbs and healing and your voice sounds like an angel when you sing. Why don’t you sing now, Stepmother?’

‘A prince needs more than a pretty face for a wife. Athelings need wives who can play politics and bring them the throne. I’d rather be in my garden than at court.’ Alwynn pointedly ignored the question about singing. Ever since she had discovered her late husband Theodbald’s treachery, she’d taken no pleasure in music. Her voice tightened every time she tried. Of all the things she’d lost, that one hurt the most.

Merri balled her fists. ‘Sometimes you have to believe in better days. You told me that. After my father died and all went wrong. And I do believe. One day, everything will come right for the both of us.’

Alwynn forced her lips to turn up. Perhaps Merri was right. Perhaps she had been far too serious for the past few months, but it was hard to be joyful when you had lost nearly everything. It had begun with Theodbald’s death from a hunting accident. He’d been drunk and had ended up being gored by a wild boar. There had been nothing she or any monk could do to save him. It was then that the true extent of the debts were revealed and she’d had to take charge. ‘Your father’s death...altered things.’

The girl gave a solemn nod, her golden curls bobbing in the sunshine. ‘I know. But there are times that I wish we still lived in the great hall with a stable full of horses.’

‘There is nothing wrong with our new hall. It is where my grandmother grew up and it does have things to recommend it. A large herb garden.’

Merri wrinkled her nose. ‘If you like plants...’

‘We have no need of princes. I will be able to hold this hall.’

‘I know my real mother watches over us from heaven, but my father?’ Merri asked in a low voice. ‘Where does he watch us from?’

Alwynn stared out at where the early-morning sun played on the sea-weathered rocks. Tiny waves licked at the shore, nothing like the gigantic ones which must have hit the beach last night. ‘He watches from somewhere else. We need to pick an entire basket of the sea coal before the sun rises much further. There is a list as long as my arm of things which need to be done today. Gode has gone to see her niece and the farmhands are out helping to shear the sheep. Plus, there is the new wheel at the gristmill that needs to be seen to.’

Alwynn didn’t add that she had no idea how to repair the gristmill properly or do a thousand other practical things. And there was no gold for a steward, even if she could find one she could trust. But they would survive. Somehow.

Merri nodded. ‘It is easier now that Gode has her own cottage. She always tries to stop me from doing the truly interesting things just because she used to be your nurse and you listen to her.’

‘And we will find something to add to your collection—maybe a shell or a feather. But no raven or falcon. We have too many mouths to feed.’

Merri tugged at her sleeve. ‘What is that over there, Stepmother? Is it a man?’

Alwynn stifled a scream. A man’s body lay on the high-tide mark. A length of rope dangled from one arm and his hair gleamed gold in the morning sunlight. But it was his physique—broad shoulders tapering down to a narrow waist—which held her attention.

For a heartbeat, she wondered what he’d been like in life. He was the sort of man to make a heart stand still.

She shook her head. Really, she was becoming worse than Merri. After Theodbald, she should know a handsome face was no guarantor of a good heart. She had to be practical and hard-hearted, instead of the dreamy soul she used to be. There could be gold or silver, something useful on his person. Anyone else would have no hesitation in searching for it. The poor soul would have no use for it if he was dead.

‘The body will have come in on the storm.’

Merri gulped. ‘Is he...?’

‘Could anyone have survived that storm? In the sea? You know about the rocks.’

‘What shall we do? Get Lord Edwin? You know what he said—no one should remain alive if they wash up on the shore.’

Alwynn tightened her grip on the basket. The last person she wanted to encounter was Edwin and his sneer. He’d claim any treasure on the body as his own.

She’d vowed to starve before she gave in to that man. And while they were not starving, raising the required gold had taken just about everything she possessed.

‘Not yet. There will be time enough for that later. He’d only ask questions...questions about...about the basket of sea coal.’

Merri nodded. ‘Good. I don’t like him.’

‘Few do.’

Alwynn swallowed hard. She hated that she’d come to this—robbing the dead. She took a deep breath and clenched her fists. She could do it. She repeated the promise she had made when she discovered the extent of Theodbald’s treachery—she would survive and Merri would marry well. One man’s debauchery would not ruin any more lives.

‘You remain here, Merri,’ she said, tucking an errant strand of black hair behind her ear. Silently she willed her stomach to stop heaving. She had tended the dead before. ‘Then you can truthfully say you had nothing to do with the body.’

‘Day by day you become more like Gode.’

‘Trust me. You want to keep away.’ Alwynn knelt down so her eyes were level with Merri’s. ‘If anyone says anything, you are blameless.’

‘I’m involved.’ Merri twisted away and kicked a stone, sending it clattering along the beach. ‘I know what my father did. If anything, I should be protecting you. He is the one who cheated you and left you with a mountain of debts. Everyone says it when your back is turned.’

Alwynn put a hand on the girl’s shoulder. Silently she prayed Merri remained in ignorance of most of it—the bullying, the whoring and the gambling which had racked up the debts. ‘The past, Merewynn. I’m concentrating on the present.’

‘If the warrior is alive, will you save him? Or will you hit him on the head like Lord Edwin commanded everyone to do?’

‘He will be dead,’ Alwynn stated flatly.

‘Lord Edwin is wrong. Surely you should know if a man is guilty before you kill him. Otherwise you become a murderer. You become like the Northmen.’