Полная версия

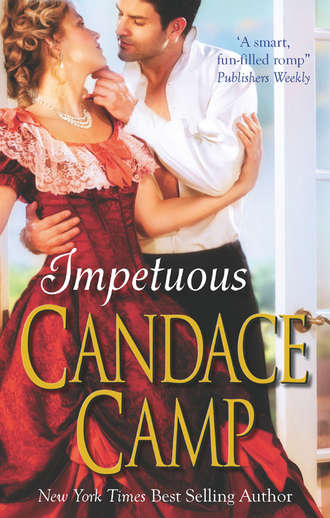

Impetuous

So Cassandra said flatly, “I am sure that they found it quite as peculiar as I that you were shouting outside Joanna’s room last night. It didn’t help that Joanna opened the door and told you that ‘he’ was not there.”

“You see?” Aunt Ardis exclaimed, rounding on her daughter. “I told you that you should not have said that. Anyone could have heard you. Why didn’t you think?”

“I suspect that Sir Philip must have heard her, too,” Cassandra added, hardening her heart to her aunt’s piteous look. “He was probably coming down the hall when you enacted your tragedy in Joanna’s doorway. No doubt he heard it all, and since he alone would have known for certain that it was he whom Joanna had invited to her room, he would have realized instantly what was going on.”

“I didn’t invite him,” Joanna protested, not very convincingly.

Cassandra did not reply. She merely cast her a look of patent disbelief that made Joanna screw up her face unattractively.

“Well, you needn’t think he is interested in you,” she huffed at Cassandra, “just because you managed to get him to walk with you in the maze. He would never have any interest in such a bookworm.”

“No doubt you are right,” Cassandra replied calmly. “As it happens, we met by accident in the maze. He seemed unable to find his way out, and I had to tell him.”

Joanna sent her a smug gaze. “You know nothing about men, Cassandra. No man likes to be told what to do.”

“How unfortunate, since so many of them seem in dire need of it.”

“Girls, please!” Aunt Ardis snapped, drawing attention back to the truly important issue—her own discomfiture. “This is not helping at all. We need to think what to do. I cannot bear to remain here with everyone staring at us and thinking that we—that you—”

“Engineered an incriminating rendezvous with Sir Philip Neville?” Cassandra suggested crisply.

“Really, Cassandra, you have a most unlady-like bluntness. It is very unappealing.”

“I’m sorry, Aunt Ardis,” Cassandra said with a noticeable lack of regret. “I am sure it must be a very trying situation for you. Perhaps we should leave.”

Aunt Ardis looked a little surprised, but a moment’s consideration had her nodding. “Yes, that’s the thing. We shall go back to Dunsleigh, and soon everyone will have forgotten this.” She frowned. “But what shall I say to Lady Arrabeck? I must not offend her.”

“Blame it on me,” Cassandra said cheerfully, knowing that was the plan most likely to please her aunt. “Say that I have been taken ill. I will go straight back to my room now, saying I feel poorly. This afternoon you can tell Lady Arrabeck how wretched I am and that I insist on returning home. Tell her you worry about me. Tell her I’m frail or something.”

“You are as healthy as a horse,” Joanna objected contemptuously.

“Lady Arrabeck doesn’t know that.”

“You don’t look sick. You look positively robust.”

“I shall do my best to look wan. Unless, of course, you would rather act the invalid.”

Joanna considered the matter, thinking of the appealing picture she would make, pale and fragile, leaning on her cousin for support as she made her weak way out to the carriage. Or she might even have to be carried out by one of the footmen—that handsome one she had seen in the hall yesterday, perhaps. Her lips curved up in a smile. “Yes, I think that would be best. It would be much more natural for Mama to be concerned about her daughter, anyway. Here, Cassandra, give me your arm.”

She put her hand through Cassandra’s arm and drooped against her. Cassandra stifled a sigh of irritation at her cousin’s dramatics, reminding herself that she would do almost anything to get out of this place and away from the odious Neville. She started slowly back toward the house with Joanna. She refused to think about the way that Sir Philip had ruined all her plans. All was not lost. She would go home and continue her search for those letters, and then...and then somehow she would figure out a way to find the Spanish dowry on her own.

Chapter Four

JOANNA ENTERED INTO her deception with such enthusiasm, applying white powder to her face for an interesting wanness and lying in her darkened room emitting effective groans and sighs, that it was all Cassandra could do not to slap her. Naturally, with Joanna “weak” in her bed, it fell to Cassandra to pack for both of them. She wondered darkly if her lazy cousin had taken that fact into consideration before she offered to play sick. It was the middle of the afternoon before Cassandra managed to get everything together and stowed away in their carriage, interrupted as she was by her aunt’s often contradictory orders.

However, finally Joanna, wrapped in a blanket, was carried down the stairs and out to the carriage by a burly, graying footman and carefully bestowed within, and Cassandra and her aunt climbed in after her. Lady Arrabeck’s daughter came out to graciously bid them farewell, and a few moments later they were wheeling at a smart pace down the drive and through the open iron gates of the estate.

“Whew!” Joanna pushed the carriage rug from her lap. “Get this thing off me. I’m sweating like a pig.”

Cassandra noted that perspiration was, indeed, making little rivulets through her cousin’s white powder. However, she said pacifically, “You put on a wonderful performance, Cousin.”

Joanna scowled. “Why did that awful old footman have to carry me down?” She was thoroughly disenchanted with the whole charade. “And no one was there to see us leave.”

“Lady Patricia,” her mother reminded her. “It was a very nice gesture, I thought.”

Joanna snorted. “She’s only the spinster daughter.”

“And so will you turn out to be, if you make many more mistakes like yesterday’s!” Aunt Ardis snapped.

“I! I made the mistake?” Joanna turned on her mother wrathfully. “It was you who came pounding on my door too early! You couldn’t wait, and it chased him away!”

“I came when we had agreed I would! He didn’t arrive on time, that’s what happened.”

“And that is my fault?”

“Yes. He wasn’t eager. You didn’t enchant him. He should have hurried to your room, and instead he dawdled.”

“I did everything I could think of! I smiled and flirted and pretended I was interested in those silly old writers he kept talking about, when I had never heard of them. I even left the lace fichu out of my afternoon dress.”

“Yes, and leaned over to pick up your fan several times,” Cassandra put in drily. “I noticed that.”

“You see. Even Cassandra saw what an effort I made,” Joanna said, oblivious to her cousin’s sarcastic tone. “The man was stone. I finally had to kiss him in the conservatory before he became at all amorous.”

“You were too fast and loose,” Aunt Ardis decided. “You made him suspicious. That is why he was lurking around, listening.”

Cassandra sighed and turned her face to look out the window, trying to ignore the bickering between her aunt and cousin and think about what she was going to do now. Despite her brave thoughts earlier, she was close to despair over Sir Philip’s rejection of her proposal. She had had such high hopes for him, had built all her schemes around his agreeing. She had been prepared for him to be difficult to deal with—he was, after all, a Neville—but she had counted on the Neville taste for accruing money to make him see the sense of their cooperating to find the dowry. It had never entered her mind that he would reject the story altogether, that he would term it a fabrication and dismiss her as a naive fool. And never in her wildest dreams would she have foreseen that he would be more interested in kissing her than in finding a treasure!

Her cheeks warmed a little even now at the thought of his mouth on hers. She had never dreamed that such kisses existed, let alone that she could turn to hot wax inside because a man did such unthinkable, immodest things to her.

Sternly she pulled her mind away from such thoughts. She ought to be working on a way to get the Spanish dowry without his help, not mooning around about him. Cassandra felt uncharacteristically like crying. Normally she was a very equable person; she liked to think of herself as calm, decisive and strong. But the thought of not being able to recapture the treasure that the Verreres had lost so long ago was almost too much for her. From the moment she had started reading Margaret Verrere’s diaries, she had realized that the dowry was the way out of her family’s problems. She had been counting on it to take her brothers and sister and herself out of her aunt’s house.

She had seen in Sir Philip’s eyes that he knew of the decline of the Verrere fortunes, but she doubted that he knew the full extent of it. Their father had died virtually penniless. She had had to sell off much of the furniture in the house to pay off his debts. She had even, heart breaking inside her chest, had to sell many of his precious books. Worst of all, she and her siblings had had to move out of Chesilworth, their ancestral home. It was a noble hall, but very old, and the years had not been kind to it. Repairs had been neglected, not only by her father, but also by his father and his grandfather before that. The west wing had been closed off ever since she could remember, because they had no money for the extensive repairs needed there. Even in the central and east wings, there were several areas where the roof badly needed to be replaced. Air leaked in around windows; floorboards were loose or bowed; almost all of the draperies were moth-eaten. Only people who loved it as much as her family did would have remained there.

But after her father’s death there was not enough money to pay even the skeleton crew of servants necessary to keep the great house running. Her family had had to leave Chesilworth and go to live with their aunt and uncle, only a few miles away in the village of Dunsleigh. The pain of leaving their home had been bad enough, but the humiliation of living on their aunt’s charity was a constant thorn in Cassandra’s side. Uncle Barlow, their mother’s brother, was a pleasant man whom they all liked, but he was rarely at home, spending as much of his time as he could in the village or in London or off hunting with his cronies. Cassandra was sure it was his wife’s shallow, venal nature that kept him away.

Aunt Ardis was a grasping woman who resented the presence of her husband’s impecunious nieces and nephews almost as much as she enjoyed lording it over them. She had never liked her husband’s sister, Delia, a vivacious butterfly of a woman who had outshone Ardis herself at every turn. Her aunt never ceased to complain about the extra expense and trouble Cassandra and her siblings entailed, just as she never hesitated to meddle in their affairs. She characterized Cassandra as a plain, mousy bluestocking of a girl, her sister Olivia as far too bold, and her brothers as young hellions badly in need of manners. She made sure that everyone, both inside and outside the home, was aware of the great sacrifice she had made in taking them in.

Joanna considered Cassandra’s quiet plainness an excellent foil for her own beauty, and she did not mind her being there as long as her own comfort was not disturbed. Crispin and Hart, Cassandra’s twelve-year-old brothers, however, were another matter. They were noisy, messy nuisances who teased her and disturbed her rest. But most of all she disliked Olivia, who at fourteen was already turning into a real beauty and a future threat to Joanna’s dominance of the small social scene in which they moved.

More than anything else in the world, Cassandra wanted to get her family out of that household and return to Chesilworth. Her uncle was the boys’ and Olivia’s guardian, and she was sure that she could talk him into letting her raise them on her own if only she had a proper house in which to live and enough money to feed and clothe them. The Spanish dowry, she knew, would provide that money. The dowry represented freedom for all four of them—and now Sir Philip had carelessly trampled all over her hopes of attaining that freedom.

“—not that great a catch, anyway.” Cassandra’s mind came back from her gloomy thoughts at the sound of her aunt’s voice mentioning Sir Philip Neville again. She looked at her aunt in some surprise.

“What do you mean? I thought you said he was one of the best catches in England,” she reminded her aunt innocently.

Aunt Ardis frowned, thinking that the girl had too good a memory. “Oh, he would be a feather in any girl’s cap,” she admitted. “But he doesn’t have a title, you know. In that respect, even Lord Benbroke surpasses him.”

“Lord Benbroke is almost sixty years old and suffers from gout.”

“Yes, Mama,” Joanna put in quickly. “Not Lord Benbroke. I just could not marry him.”

“I didn’t mean that you should marry him, only that he had a title and Neville doesn’t. And I am sure that there are those more wealthy than he.”

“I have heard that Richard Crettigan is quite the richest man in the country,” Cassandra offered.

Aunt Ardis looked shocked. “Richard Crettigan is a...a merchant!”

“Yes, and from Yorkshire, too. Can you imagine listening to that accent all your life?” Joanna shook her head in dismay.

“But it must be comforting to know that at least there are other options for Joanna.” Cassandra returned her aunt’s and cousin’s suspicious gazes blandly.

“I have heard,” Aunt Ardis said loftily, ignoring Cassandra’s comment, “that Sir Philip is a libertine.”

Cassandra’s stomach tightened. “A libertine? Who said so?”

“I heard it from Daphne Wentworth, who told me it was common knowledge all over London. Of course, that whey-faced Teresa of hers had made no bones about setting her cap for him, and Daphne no doubt wanted no competition. Still, Mrs. Carruthers was sitting right there when she said so, and she agreed that he had a certain reputation.”

“A reputation for what?” Cassandra pressed. She wasn’t sure why her aunt’s words irritated her so, but she found herself wanting to deny them hotly.

Aunt Ardis lowered her voice conspiratorially and said, “For seduction.”

“Oh, really, Aunt Ardis, how would they know?” But despite her words, Cassandra could not help thinking of Sir Philip’s kisses and the way they had made her melt inside. She had to admit that he had seemed incredibly expert at what he was doing. Besides, there was the fact that he had made advances toward her. Cassandra did not fool herself that she was any great beauty. It followed then that Sir Philip must be interested in kissing any woman who happened to come across his path. She squirmed a little inside at the thought. “It is all rumors.”

“It’s more than rumors. I’ve heard things...” her aunt hinted darkly.

“What things?”

“The sort of things that young ladies like you and Joanna should not hear.”

“Oh, Mama...” Joanna slumped back against her seat disgustedly. “You always say that.”

Cassandra thought privately that as Joanna had set out to seduce Sir Philip into a compromising position in her bedroom, she was hardly an innocent creature whose ears should not be sullied, but she managed to keep from saying so. There was no point in getting into a wrangle with her aunt over something as unimportant as Sir Philip Neville and his reputation.

The truth was, she told herself sourly, that he was probably exactly the sort of creature that gossip had painted him. It was absurd that she should be standing up for the man who had dashed her hopes.

She turned her head to look out the window, and they continued the ride in silence.

* * *

CASSANDRA’S HEAD JERKED up, and she blinked, looking around. She realized that she had been asleep, as were her aunt and cousin in the seat across from her. She pushed aside the window curtain and peered out. It had grown dark while she slept. Her stomach growled, giving her another reminder of how long they had been traveling.

She realized that what had awakened her must have been the carriage turning, for even in the pale moonlight she could recognize the narrow lane they traveled as the one branching off toward her aunt’s house. They were almost home. Her spirits lifted in anticipation. Everything would seem better, she knew, when she was with her family.

The carriage pulled up in front of a Georgian mansion a moment later, and the front door opened. A footman hurried down to open the carriage door.

“Mrs. Moulton.” He sketched a bow in the direction of Aunt Ardis and reached up to give her a hand down.

Aunt Ardis gave him a slight nod and swept on to the front door, Joanna trailing her. Cassandra came out of the carriage last, taking the footman’s proffered hand and smiling. “Hello, John.”

A smile broke the man’s usually impassive countenance, and he said warmly, “Hello, miss. It’s good to have you home.”

“Thank you. How is your sister? Has she had the little one yet?”

“No, miss. We’re all on pins and needles.” Like most of the servants of Moulton Hall, John Sommers felt that the place had been much improved by the arrival of the Verrere family. Unlike his mistress and her daughter, the Verrere children knew everyone’s names and were always ready with a smile or a word of thanks. There had been many times when a vase broken by one of the running boys had been swept up and thrown away with never a mention made of it, and a secret supper had often been sent up to the nursery when Olivia or the twins were in disgrace about some misdeed or other.

“Cassie!” A pair of towheaded boys tore out the front door and bounded down the front steps two at a time, followed not much more sedately by a girl in blond braids.

Cassandra threw her arms wide and swept all of her siblings in. “Crispin! Hart—what happened to your hand? Olivia—oh, I think you’ve grown even prettier while I was away.”

Olivia, whose braids and childishly shorter skirts could not hide the rapidly maturing body and face of a young woman, giggled at her sister’s words. “Pooh—you haven’t been gone but three days. What happened? Why are you home early?”

“Yeah!” Crispin added. “You should have seen Uncle Barlow’s face when he heard John announce that the carriage was home. He looked like a hare that had heard the hounds.”

Hart giggled. “He was looking all over like he thought there might be a hole he could bolt into.”

“He’s been home every night since Aunt Ardis left, and it’s been ever so nice. He lets us eat dinner with him, and we talk about all sorts of things. It wasn’t as good as being with Papa, but it reminded me of home, a little....” Olivia’s voice trailed off wistfully.

Cassandra felt tears spring into her eyes. “I know, Olivia. I miss him, too.”

“It was bang-up!” Hart, who had enjoyed his uncle’s discussion of his hunting dogs far more than his father’s scholarly ramblings, added, “He said he would take us hunting with him next time he went to Buckinghamshire, if Aunt Ardis will let him.”

“Hah! Let us have fun? Not likely.”

“Now, hush, Crispin. Aunt Ardis might be well pleased to have the two of you out of the house. I shall endeavor to point out the advantages in terms of dirt and noise of having two twelve-year-olds gone from here.”

“Would you?” The twins’ expressions brightened. In their experience, Cassandra was able to do anything she put her mind to. It had been she who had always made the household budget stretch to include entertaining outings or a pony to ride or a cricket bat to replace the broken one.

“Of course I will. I’m not promising, mind you....”

“I know.” Crispin nodded gravely. A more serious boy than his twin, he realized better than Hart that Cassandra’s ingenuity and intelligence were not always sufficient weapons against their aunt’s power.

“Forget the silly hunting!” Olivia said impatiently. “Tell us what happened at the house party, Cassandra.”

“Did you meet Sir Philip?” Hart stuck in eagerly. “Is he going to help us?”

“Just a minute. I shall tell you all about it later. Let’s go in now and let me say hello to Uncle Barlow.”

She did as she said, noticing with amusement that her poor uncle did indeed look like a trapped hare as he stood in the entryway listening to his wife’s strictures on the excessive number of candles that had been lit throughout the house.

“Why, I could see from the carriage that the nursery was lit up like Christmas,” Aunt Ardis was saying as the Verreres walked in. “There is no reason for that. The children ought to be in bed anyway.”

“It didn’t seem much light to me.” Uncle Barlow tried to defend himself. “There was Olivia trying to read by the light of one candle, and she mustn’t strain those pretty eyes, you know.” He smiled benignly at his niece, not realizing, even after years of living with Ardis, that he was saying exactly the wrong thing. “Those eyes will be her fortune.”

“What nonsense! Olivia shouldn’t be reading all those heathen books, anyway,” Aunt Ardis sniffed, frowning toward her younger niece. “Olivia, straighten your skirts, you look like a hoyden. And your hair is all everywhere.”

“Yes, Aunt Ardis,” Olivia answered in a carefully colorless voice. Her high spirits had gotten her into trouble with her aunt more than once, but once she had realized how much her battles with Aunt Ardis caused Cassandra to suffer, she had learned to curb her ready tongue.

Cassandra gave her uncle a quick hug and a peck on the cheek, and whisked her brothers and sister upstairs to the bedroom shared by the two girls. The boys flopped down on the rug, and Olivia hopped onto the bed, curling her legs beneath her.

“All right,” she told her older sister eagerly. “Now tell us all. Why did Aunt Ardis come home so early?”

“Who cares about that?” Crispin retorted scornfully. “I want to hear about Sir Philip and the treasure.”

“Aunt Ardis and Joanna met with a little setback,” Cassandra told her sister, eyes twinkling, and cast a significant look at her brothers. “I shall tell you about it later.” She did not add that her younger sister would receive a carefully edited version of Joanna’s escapade.

Olivia’s eyes widened, but she made no demur as Cassandra started on the story that the brothers wanted to hear. “I am afraid the news is not good. Sir Philip refused to help us.”

Crispin groaned, and Hart sneered. “I knew we couldn’t count on a Neville. Papa always said so. You shouldn’t have asked him.”

“I don’t know how else we’re supposed to find it,” Crispin reminded him. “The Nevilles have the rest of the clues or the map or whatever it is.”

“We don’t need it,” Hart said stoutly. “Do we, Cassie? We can find it by ourselves.”

“Of course we will.” Cassandra plastered a heartening smile on her lips. “It will merely take us longer. I don’t intend to give up.”

“But how are you going to do it?” Olivia questioned. Though she had as much faith in her older sister as the twins did, she had a more practical bent of mind.

“The first thing is to find the old letters. I shall keep going over to Chesilworth every chance I get to search the attics. Once I actually have the letter in my hands, I can prove to Sir Philip that the treasure really was hidden and can be found. Then he will surely agree to help us look for it.” It was the best plan that Cassandra had been able to come up with, and though it sounded rather flimsy to her ears, she hoped it would satisfy her siblings.

“You mean he didn’t believe in the treasure?” Hart looked shocked at such heresy.

“No. He thought the diaries were something someone made up just to get Papa to buy them. He’s a very stubborn, narrow-minded man. But once he sees the evidence with his own eyes, he will have to believe me.”

“We shall help you look,” Crispin told her gravely. Though he was as high-spirited as any lad his age, he was also aware that he was now Lord Chesilworth, and he took his responsibilities seriously. While Hart might look on the hunt for the dowry as a wonderful adventure, Crispin knew that it also meant the very future of Chesilworth.

“Of course,” Olivia agreed. “Whenever that old battle-ax isn’t looking, we’ll sneak over.”