Полная версия

To Hell in a Handcart

‘I mean, the law centre. You can’t turn your back on that.’

‘I can do whatever I please, or do you only pretend to believe in women’s lib?’

‘Of course not. That’s not fair. You know I’m committed to the Project. That’ s why I’m doing it.’

‘But, the police, for God’s sake. They’re the enemy. You’ve always agreed on that. You saw what they did to the gay rights marchers. You were on that picket line at the power station. They’re animals, pigs.’

‘Precisely,’ Roberta replied with a self-satisfied smirk. ‘And what do you do with animals?’

‘Liberate them?’

‘Don’t be daft, they’re not smoking beagles or laboratory rats.’

‘What then?’

‘You train them.’

‘Train them?’

‘Haven’t you ever heard the expression, if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em?’

‘Sure.’

‘Well, we’re never going to beat them. Not by marching and demonstrating. That’s for students and idealistic dreamers. It’s waning in public.’

‘But we’ve had some successes.’

‘Such as? A few occupations, petitions? Stopping the traffic outside the Old Bailey? Gestures. You can’t beat the system from without. You have to be within it to make any real difference. We have got to capture the institutions.’

‘But that could take years.’

‘About twenty, I reckon. Maybe twenty-five years at the outside.’

‘But that’s an entire lifetime.’

‘Only if you’re in your twenties. Look at the bigger picture, Justin. You’ve got a brain, use it. Ask yourself who, eventually, is going to have the biggest influence on the way society works – a 45-year-old overgrown student activist, pissing around on the fringes? A middle-aged trades union leader, locked outside the factory gates? A 45-year-old journalist churning out agitprop bollocks in a small circulation revolutionary newspaper on sale outside Woolworth’s? A 45-year-old lawyer up to his arse in housing benefit applications and claims for wrongful arrest? Or a 45-year-old judge, a 45-year-old Cabinet minister, a 45-year-old editor of a national newspaper, a 45-year-old Commissioner of Police?’

‘Hmm,’ mused Justin, downing his rough red wine and pouring another from the bottle on the mantelpiece, perched next to a six-inch bust of Karl Marx, under the watchful eye of a Che Guevara poster on the voguish mud-brown wall. He wiped a tumbler with his discarded T-shirt, filled the glass and handed it to Roberta, still lying naked on the futon.

Two middle-class kids with law degrees, fresh out of university, sharing a top-floor bedsit in shabby Tufnell Park, their lives stretching out before them. It was a nowhere district between the Holloway Road and Kentish Town, north London, a tube station between King’s Cross and Finchley Central, two and sixpence, Golders Green on the Northern Line. And it didn’t have a park.

Roberta was plain, but that’s the way she liked it. At 5ft 7ins, she was stocky, not fat, with full hips and firm tits like rugby balls, and had nipples you could hang a child’s swing on. She favoured kaftans and sensible shoes. Daddy was a vicar, the Rev Robert Peel, in an affluent part of Surrey. He had wanted a son, so Roberta was named for him. Mummy something in the WI, a parish councillor and magistrate. Roberta was an only child and she was pampered, at least to the fullest extent of a parson’s C of E stipend.

They were thrilled when she left her all-girls grammar school and went off to university to study law. Roberta was sad to leave St Margaret’s, not because she was loath to shed the shackles of school. She had a crush on the games mistress.

Justin was the son of Edward Fromby, sole proprietor of Fromby & Fromby, the biggest retail coal merchant in Nottinghamshire, and, as he always referred to her at the Round Table cheese and wine evenings, his lady wife Mary.

Justin was christened Edward Albert Fromby, like his father, his grandfather and his father before him. Mr Fromby Snr wanted his only son to follow him into the coal and smokeless fuel business. But Edward Jnr persuaded him that the discovery of North Sea oil and gas would spell the end of the retail coal business.

After the miners’ strikes of 1972 and 1974, no government was ever going to allow the nation to be almost wholly dependent on a dwindling resource subject to frequent interruption on the whim of a union run by Communists. He was very convincing. Secretly young Edward admired the Communists who ran the National Union of Mineworkers, but was too scared of his father to mention the fact.

Edward Fromby Snr was nothing if not a pragmatic man. ‘I’m nothing if not a pragmatic man,’ he said frequently. ‘You don’t succeed in the retail coal business without a healthy helping of pragmatism.’ He acknowledged the merit in his son’s argument and, after unsuccessfully trying to persuade him to go into the North Sea oil business, agreed that he should go to university to study law, hoping that he would return and get himself articled to the town’s leading firm of solicitors, perhaps one day becoming senior partner.

Young Edward had a different compass. Wills and conveyancing held no attraction for him. He wanted to be a street lawyer, fighting for the rights of the downtrodden, the workers, the oppressed minorities. He wasn’t going back to Nottinghamshire. He was going to London.

As soon as he got to the LSE, he dropped the Edward Albert and adopted Justin as his given name. Very Seventies, he thought. And if anyone asked about his family, he simply said his dad worked in the Nottinghamshire coalfields. He was careful not to lie but not to tell the whole truth, either. He must have been cut out to be a lawyer.

‘Justin. That’s a funny name for a coal-miner’s son,’ Roberta remarked when they were introduced.

‘Hmm, yes, I suppose so. I wasn’t christened Justin actually, but whenever I came home from school, my mother would call out “You just in, are you?” and it sort of stuck. A bit of a family joke,’ he claimed. He almost believed it himself.

‘So what were you christened?’

‘Oh, it doesn’t matter.’

‘You’re right. It doesn’t matter. What’s in a name? This is the 1970s. We can be who we want to be. If you want to be Justin, that’s fine by me.’

Their friendship was forged at university. They weren’t so much lovers as good friends who had sex sometimes, usually unsatisfactorily for both of them. But neither was experienced and neither was sure what to expect. Perhaps that was all there was to it. Roberta had been cloistered in an all-girls school and opportunities for adventures with the opposite sex were limited. Justin, or Eddie as he then was, had been an awkward, lanky youth. His overbearing mother had discouraged him from forming relationships with girls.

At university, Roberta experimented with other men, but they were usually pissed and it didn’t seem much of an improvement on what she had with Justin. For his part, Justin didn’t seem to mind who she slept with. Their friendship transcended the sexual. He contented himself with his studies and increasing involvement in student politics.

Their relationship was more brother and sister, even if it was occasionally incestuous.

They were at ease with each other. They squabbled but had few hang-ups. They were not embarrassed to be naked together, or to bare their emotions.

Justin and Roberta lay on the futon and drained the last of the Bulgarian Beaujolais. Justin rolled a joint, which he liked to smoke with cupped hands, Rastaman style.

‘Hey, stop hogging that,’ Roberta complained. ‘Pass it here.’ She sucked hard and inhaled the weed, holding her breath for several seconds before releasing the smoke.

‘This will have to stop, you know.’

‘What?’

‘Dope, booze. If you join the police.’

‘There’s no if about it. I have joined. I start two weeks on Monday.’

‘Better make the most of it, then.’

He passed her the joint again. She took it, greedily.

‘You sure it’s worth it?’

‘One hundred and fifty per cent certain. You are sharing a joint with the future commissioner of the Metropolitan Police,’ she wheezed.

‘Get real.’

‘This is real. You watch me. And if you take my advice, you’ll get out of that law centre and find yourself a proper job with a real law firm. Make a difference, Justin. Make a difference. You can do your pro bono social work in your spare time. We’ve grown out of “the revolution starts when this pub closes” stage of our lives. The revolution starts now.’

‘If you’re serious about this police thing, you’re going to need me. You’re going to have to make compromises, bite your lip, never let go in public. But there will always be somewhere for you to come. I will always be here for you. I will keep your secrets and never betray you. I do love you.’

‘Then make love to me,’ she demanded.

This was the bit Justin was dreading. He adored Roberta, loved to lie naked with her, but somehow the sex thing didn’t really work for him. Still, he tried.

He rolled on top of her and kissed her dirigible breasts, almost choking on her rigid nipples.

‘Fuck me. Fuck me hard,’ she pleaded. ‘Inside me, now.’

They’d already made love once that evening and it had been over in an instant. He’d taken her from behind. He found that doggy-fashion, in the dark, was the only way he could muster any enthusiasm. Twice in a night was asking a bit much and this time she wanted it on her back, with the light on.

Roberta reached down, ripped off his pants and squeezed his balls, but the best he could manage was a lazy lob.

By now she was frenzied, as the alcohol and narcotics kicked in, maybe for the last time in her life.

She grabbed his cock and pulled it towards her, willing him to harden. But it was no good. It was like trying to push a marshmallow through a letter box.

‘Sorry, sorry, sorry,’ Justin kept repeating. ‘It must be the dope, or the booze or both. Just give me a minute.’ He so wanted to please her.

But Roberta didn’t have a minute to spare.

She reached up and lifted the six-inch bust of Karl Marx off the mantelpiece.

She lay back on the futon, raised her sturdy arse, parted her knees and thrust the father of international socialism head-first between the thighs of the future Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police.

Five

Now

‘You’re listening to the Ricky Sparke show on Rocktalk 99FM. Let’s go to George on line one. Morning, George. Good to have your company today. What can we do for you?’

‘Hello?’

‘Hello.’

‘Can you hear me?’

‘Loud and clear, George.’

‘Er.’

‘Fire away, George. We’re waiting.’

‘You can hear me?’

‘Yes George. You’re live on air.’

‘Is that you, Ricky?’

‘No, it’s the Samaritans, George.’

‘What?’

‘George, you’re live on Rocktalk 99FM. You rang us. A nation awaits your pearls of wisdom.’

‘Well, like, what I wanted to say was, er …’

‘Get on with it, George. I can’t wait much longer. I’m losing the will to live.’

‘Well, you know, it’s about these beggars, like.’

‘What about them?’

‘Well, er, something should be done.’

‘And what precisely do you have in mind?’

‘Dogs.’

‘Dogs, George. I see.’

‘They should set the dogs on them.’

‘What dogs?’

‘Police dogs, I dunno. Any kind of dog.’

‘Alsatians?’

‘Yeah. And Dobermans and Rottweilers.’

‘Yorkshire terriers, miniature poodles?’

‘Are you taking the piss?’

‘Perish the thought, George. It’s just that, well, don’t you think dogs are a bit drastic? How about firehoses?’

‘Firehoses. Yeah, why not? That’s a great idea.’

‘Flamethrowers?’

‘I don’t care, I just want them off the streets and back where they came from. It’s not safe for a little old lady to go out of the house without being mugged or raped by these beggars …’

‘Ah, yes … I was wondering when the little old lady would turn up. She normally makes an appearance whenever anyone runs out of rational argument. Tell me, George, when exactly was the little old lady in question last mugged or raped by a beggar?’

‘I’m not taking anyone pacific, like.’

‘Specific.’

‘What?’

‘Specific. The Pacific is an ocean.’

‘Anyway, it could happen if something isn’t done. These Romanians are a bloody menace. They should be rounded up at gunpoint and sent back to Rome where they belong.’

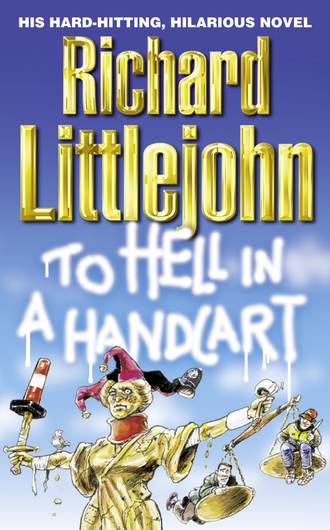

‘Goodbye, George. Don’t bother ringing us again. It’s coming up to midday. That’s all we’ve got time for today and this week, thank God. Join me again at the same time on Monday for another unbelievable assortment of losers and lunatics live on Rocktalk 99FM. Until then, this is Ricky Sparke, wishing you good morning and good riddance. We are all going to hell in a handcart.’

Ricky removed his headphones and threw them onto the console next to the cough-cut button and a rack containing eight-track cartridges. The red on-air light was extinguished, indicating his microphone was switched off. He put his feet up on the desk, lit a cigarette and leaned backwards.

Where on earth do we find these people? It was the same every day, a telephonic procession of inarticulate imbeciles, radio’s answer to the fish John West reject.

Ricky had one underpaid, overworked producer in charge of everything from the running order to making the tea and working the fax machine. His only back-up was a girl on a work experience scheme who couldn’t operate the phones properly and appeared to be clinically dyslexic.

Rocktalk 99FM was the latest incarnation of a station which had started life eight years earlier as Voice FM. Its founders had won the franchise by persuading the Radio Authority they planned to broadcast a cerebral schedule of original drama, discussion, debate and documentaries dedicated to politics, humanitarian issues and the arts. It was going to sponsor live concerts and forums and gave a solemn and binding guarantee to recruit at least forty per cent of its staff from the ranks of the ethnic minorities.

That was the theory, anyway. The ‘promise of performance’ document managed to impress the assorted worthies who make up the Radio Authority, which regulates the commercial sector, and Voice FM was awarded a ten-year licence.

Six weeks before the station went on air, the founding fathers received an offer they couldn’t refuse from an Australian consortium desperate to break into the British market. They trousered the thick end of £15 million between them and withdrew to spend more time with their mistresses.

When Voice FM was launched, it bore little resemblance to the original pitch. Having spent most of their money actually buying the licence, the Australians had virtually nothing left over to spend on content. Out went original drama, documentaries and live concerts.

There was certainly discussion and debate, if that’s what you call cabbies from Chigwell complaining about cable-laying and bored housewives ringing agony aunts with their mundane grievances and PMT remedies.

As for recruiting from the ethnic minorities, that promise was kept, up to a point. The security officer was Bosnian and the cleaners were all illegal immigrants from Somalia.

Two years on, Voice FM was relaunched as Bulletin FM, a cheap-and-cheerful rolling news station, hampered by the fact that it didn’t actually employ any correspondents, just a roster of failed actors hired to read out agency reports and stories copied out of the newspapers and off the television by kids on work experience.

The traffic reports were delivered by one Ronnie Dugdale, an alcoholic ex-bus driver who had once enjoyed fifteen minutes’ fame as a contestant on Countdown. He was the first player to score nil points, failing to muster any word over four letters and missing the target on the numbers board by more than two hundred. After the show he was escorted from the green room by security for attempting to grope Carol Vorderman, the show’s attractive co-presenter. On the way home he was breathalysed, disqualified from driving for two years and sacked from the bus company. Still, it made him a minor celebrity and minor was all the celebrity Bulletin FM could afford.

When the motoring organizations withdrew co-operation because they hadn’t been paid, Ronnie took to making up his traffic reports, which became increasingly bizarre as the day wore on and he shuttled backwards and forwards between the Bulletin FM studios and the Red Unicorn over the road. One afternoon, he arbitrarily announced the closure of half a dozen main arteries and advised drivers to avoid Westminster and Waterloo Bridges because of a fictitious demonstration and march by 20,000 dwarves, demanding equal rights for the vertically challenged.

Unfortunately, thousands of drivers took him at his word. It caused gridlock in central London on an unprecedented scale. The Strand was still jammed at two o’clock the following morning. He was fortunate charges were not preferred.

That was the end of Ronnie’s radio career. Last heard of he was awaiting trial for driving a minicab through the front of a halal butcher’s shop while several times over the limit and while still serving a suspended sentence for driving while disqualified, without insurance, road tax or a valid MOT certificate.

It was also the end of what passed for Bulletin FM’s credibility. The station’s owners decided that rolling news was not the way ahead and convinced themselves that sport was the next big thing. Having seen the success of Sky, they decided to launch a dedicated football station, Shoot FM. Not actually having the commentary rights to any live football, they were reduced to inviting listeners to call in match reports on their mobiles from the back of the stands. This lasted about six weeks, until the lawsuit landed from the Premier League. Shoot FM struggled on, covering non-league football and commentating on the Spanish Primera Liga, until Sky realized it was being ripped off and the commentator was in fact sitting in Shoot FM’s studio watching the game on Sky Sports Three.

With three years left on the licence, the Aussies played their last card. Scouring the franchise document they discovered it allowed them to play forty per cent music by content. They decided they could always fill the other sixty per cent with phone-ins and thus Rocktalk 99FM, a mixture of classic rock and pig-ignorance, was born.

It coincided with Ricky Sparke, controversial columnist, being shown the door by the ailing Exposer, a downmarket tabloid aimed primarily at the illiterate and famous for being the first Fleet Street publication to feature full-frontal nudity.

The Exposer was Ricky Sparke’s last-chance saloon as far as newspapers were concerned. He’d blown more jobs than Linda Lovelace, largely through drink and an inability to tolerate fools. He was a gifted polemicist but had a history of throwing typewriters through windows if some lowly sub-editor changed so much as a single syllable of his prose.

For once, drink and madness played no part in Ricky’s downfall. His contract had run its course and the editor decided there was no longer any point in paying £100,000 a year to a wordsmith for a once-a-week column, given the fact that few of his readers could actually read.

Ricky was replaced by a former lap-dancer who dispensed sex advice in the form of a comic strip with voice bubbles, True Romance-style. When her first column appeared, readers were invited to take part in a competition to describe in no more than twenty words why they’d like to give her a bikini wax. The winner got to give her a bikini wax. Ricky entered under a false name and came second.

Ricky had frequently appeared on Voice FM, Bulletin FM and Shoot FM as a guest pundit, filling the voids between callers with sarcastic banter and mock outrage. It didn’t pay much but there was always a steady supply of drink in the studio, which Ricky reckoned at least saved him a few bob. He was quite good at it, too.

When Rocktalk 99FM was launched, Ricky received a call from Charlie Lawrence, the programme director, who offered him a job as the mid-morning presenter.

Lawrence was a former salesman who started off selling solar-powered boomerangs to tourists at Circular Quay in Sydney, wound up in newspaper telesales and graduated to promotions manager at an ailing talk-radio station.

He transformed the station, turning it into Down Under AM, Australia’s first all-gay on-air chatline.

Lawrence shipped up in London, headhunted by Rocktalk FM’s Australian management in an act of desperation.

‘We need controversy, we need to provoke people. We need someone who’s not afraid to speak his mind. You’re the man, mate,’ Lawrence had insisted over a bottle of Polluted Bay Chardonnay.

Ricky didn’t take much persuading. He was also available. What Lawrence didn’t know was that Ricky had already been told his contract at the Exposer wasn’t being renewed and that he had nowhere else to go.

Ricky was almost potless. Although he had always been handsomely paid, his prodigious thirst and the mortgage on his flat in a mansion block at the back of Westminster Cathedral swallowed his earnings. He could just about manage to service his credit cards and his extended bar bill at Spider’s.

He could have lived somewhere cheaper, but he needed to be at the centre of town. He also liked being driven, especially since the London Taxi Drivers’ Association had blacklisted him following a column in praise of minicabs. Ricky only discovered this when he clambered into the back of a black cab in Soho one night and asked to be taken home.

The driver looked at Ricky in the mirror and checked. He took a newspaper cutting off his dashboard, held it up to the vanity light, inspected it and turned to get a better look at his dishevelled passenger.

‘You’re him, aren’t you?’

‘Eh?’

‘Sparke. You look older in real life. And fatter. But I can tell it’s you.’ The driver was clutching Ricky’s picture by-line, torn from the pages of the Exposer. It had been taken some years earlier in a professional studio and enhanced by Fleet Street’s finest photographic technology. Although Ricky had worn badly over the years, it was still recognizably him.

‘OK, so it’s me. Give the man a coconut. Now take me to Westminster.’

‘You must be kidding, mate, after what you said about us. You’re barred.’

‘Then take me to the public carriage office. You can’t do this.’

‘I can do what I like. Now get out. Go on. Out!’

Ricky stumbled out of the cab and retraced his steps downstairs into Spider’s. Dillon laughed when Ricky told him the story, gave him another one for the strasse on the house and called a local chauffeur firm to take him home.

When the car turned up, it was being driven by former police sergeant Mickey French, an old mate Ricky had known since the Seventies, when he was a local newspaper reporter and Mickey was PC at Tyburn Row, although he hadn’t seen him for a couple of years. Mickey took him back to his flat, declined an offer of a drink and said he’d call Ricky in the morning. Since that night, Mickey had been Ricky’s regular ride around town.