Полная версия

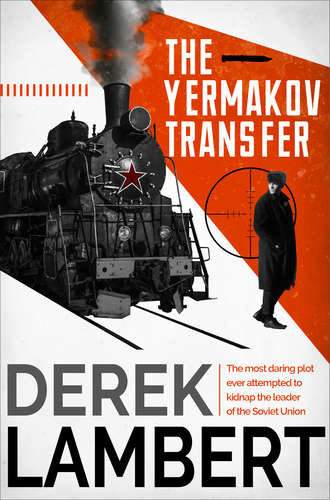

The Yermakov Transfer

The officers walked respectively past Yermakov who stared at them closely, communicating apprehension which made them feel a little sick. He had just remembered that, in the old days, it was considered unlucky to travel on the Trans-Siberian on a Monday.

FIRST LEG

CHAPTER 1

The kidnap plot was first conceived by Viktor Pavlov in Room 48 of the Leningrad City Court at Fontanka on December 24, 1970.

On that day two Jews were sentenced to death and nine to long terms of imprisonment for attempting to hi-jack a twelve-seater AN-2 aircraft at Priozersk airport and fly it to Sweden en route to Israel.

At the back of the courtroom, which seated 200, Pavlov listened contemptuously to the details of the botched-up scheme. When he heard the evidence of one of the accused, Mendel Bodnya, revulsion burned inside him like acid.

Bodnya told the court that he had yielded to hostile influence and deeply regretted his mistake. He thanked the authorities for opening his eyes: he had only wanted to go to Israel to see his mother.

Bodnya got the lightest sentence: four years of camps with intensified regime, with confiscation of property.

Pavlov’s contempt for the other amateurs was tempered by admiration for their brave, hopeless idealism.

The woman Silva Zalmanson in her final statement: “Even now I do not doubt for a minute that some time I shall go after all and that I will live in Israel.… This dream, illuminated by two-thousand years of hope, will never leave me.”

Anatoly Altman: “Today, on the day when my fate is being decided, I feel wonderful and very sad: it is my hope that peace will come to Israel. I send my greetings today, my land. Shalom Aleikhem! Peace unto you, Land of Israel.”

When the sentences were announced Pavlov joined the disciplined applause because he had cultivated the best cover there was – anti-Semitism. A woman relative of one of the defendants rounded on him: “Why applaud death?” He ignored her, controlling his emotion as he had controlled it so often before. He was a professional.

He watched impersonally as the relatives climbed on to the benches weeping and shouting. “Children, we shall be waiting for you in Israel. All the Jews are with you. The world is with you. Together we build our Jewish home. Am Yisroel khay.”

With tears trickling down his cheeks an old man began to sing “Shma Yisroel”. The other relatives joined in, then some of the prisoners.

Viktor Pavlov sang it too, silently, with distilled feeling, while he continued to applaud the sentences. Then the local Party secretary who had collected the obedient spectators realised that the hand-clapping had become part of the Zionist emotion. Guiltily, he snapped, “Cease applause.” Another amateur, Pavlov thought as he stopped clapping: each side had its share of them: the knowledge was encouraging.

At 11 a.m. on December 30, at the Moscow Supreme Court, after a sustained campaign of protest all over the world, the two death sentences were commuted to long sentences in strict regime camps and the sentences on three other defendants reduced.

While the Collegium of the Supreme Court was deliberating the appeals Pavlov waited outside noting the identity of a couple of demonstrators. With their permission he would later identify them to the K.G.B. at their Lubyanka headquarters opposite the toy store. They would be locked up for a couple of weeks for hooliganism and his cover would be strengthened.

The Jewish poet, Iosif Kerler, was giving interviews to foreign correspondents. The Leningrad verdict, he told them, was a sentence on every Jew trying to get an exit visa for Israel. But Pavlov knew there was no point in laying information against Kerler: the police had a dossier on him and there was nothing poetic about it. Nor was there any point in informing on the Jewess from Kiev who was telling correspondents about her son dying in Jerusalem: the K.G.B. had her number, too.

No, the information had to be new and comparatively harmless. Pavlov had an arrangement with a Jewish schoolteacher who didn’t mind a two-week stretch during the school holidays. He wore a piece of white cloth pinned to his lapel bearing in Hebrew the slogan NO TO DEATH with a yellow, six-pointed Star of David beneath it. He meant well but he was over-playing his hand; it was like laying information against a man walking across Red Square with a smoking bomb in his hand. A pretty Jewess had also agreed to serve a statutory two-week sentence. Pavlov would report that she had been chanting provocative Zionist slogans; although she had been doing nothing of the sort because, like Pavlov, she had little time for pleas and protests; Israel was strength and you didn’t seek entry with a whine. Pavlov stared at her across the crowd; she stared back without recognition; she, too, was a professional.

Among the correspondents Pavlov noticed the American Harry Bridges. Tall, languid, watchful. He had the air of a man who had the story sewn-up. He didn’t bother interviewing the demonstrators and managed to patronise the other journalists. Pavlov admired him for that; at the same time he hoped he would rot in hell.

When the success of the appeals was announced the demonstrators sang and shouted their relief. Viktor Pavlov felt no relief; now the amateurs had even lost their martyrdom. They had perpetrated an abortion: he was conceiving a birth.

* * *

Viktor Pavlov belonged to that most virulent strain of revolutionaries: those who don’t wholly belong to the cause they are fighting for. He was fighting for Soviet Jewry and he was only part Jewish.

Sometimes his motives scared him. Why, when so many full-blooded Jews advised “Caution, caution” did he, a mongrel, call for “Action, action”? What worried him most was the sincerity of his conviction. Was the scheming and inevitable brutality merely a heritage? – a family tree planted in violence? And the right of the Jews to emigrate to Israel: Was that merely a facile cause?

Passionately, Viktor Pavlov sought justification. He found it mostly in the richness of his Jewish strain of blood. So deeply did he feel it that it sometimes seemed to him that it had a different course to his gentile blood.

His great, great grandparents had been Jews born in the vast Pale of Settlement in European Russia where the Tsars confined the Jews. After the murder of Alexander II the Jews became scapegoats and Pavlov’s ancestors were exiled to Siberia to one of the mines which produced 3,600 pounds of gold loot a year for Alexander III.

The persecution of the Jews continued and Viktor Pavlov found deep, bitter satisfaction in its history. Scapegoats; they were always the scapegoats. In 1905 gangs like the Black Hundreds carried out hundreds of pogroms to distract attention from Russia’s defeat – its debacle – at the hands of the Japanese. Followed in 1911 by the Beilis Case when a Jew in Kiev was accused, and subsequently acquitted, of the ritualistic murder of a child.

By this time the Jewish blood that was to flow in Viktor Pavlov’s veins had been thinned. His grandmother, Katia, married a gentile, an ex-convict who helped to build the Great Siberian Railway and became a gold baron in the wild-east town of Irkutsk.

Here Pavlov’s soul-searching got waylaid. His great grandfather lived in a palace, brawling, whoring and gambling and using gold nuggets for ashtrays. He was a millionaire, a capitalist, and thus an enemy of the revolutionaries – a White Russian. Most of the Jews were Reds.

Pavlov allowed his great grandfather to retreat from his deliberations; across Eastern Siberia during the Civil War where he was finally shot by the American interventionists who were not always sure which Russians they were supporting – Reds or Whites.

Pavlov concentrated on World War I. Scapegoats again. The Tsarist government, trying to explain its shattering defeats by the Germans, blamed traitors in their midst. Jews, naturally.

Then, after the Revolution, the Jews came into their own. The Star of David in ascendancy; but too brilliantly, too hopefully, a shooting star doomed to expire. The Jews were among the leaders of the October Revolution and, with an optimism which had no historical foundation – bolstered by the Balfour Declaration in November, 1917 – they anticipated the end of persecution. They were Russians, they were Bolsheviks, they were Jews.

Even V. I. Lenin lent his support in a speech in March, 1919:

“Shame on accursed Tsarism which tortured and persecuted the Jews. Shame on those who foment hatred towards the Jews, who foment hatred towards other nations.

“Long live the fraternal trust and fighting alliance of the workers of all nations in the struggle to overthrow capital.”

Today, Viktor Pavlov thought, it was Leninism that he was fighting.

During the Civil War his grandfather, half-Jewish, a rabid Bolshevik, fell in love with a wild Jewish Muscovite who wore a red scarf and gold earrings. Illegitimately, they sired Pavlov’s father.

According to Pavlov’s father, Leonid, they had always intended to marry. But when the shooting star faded and Stalin, frightened of the Jewish power around him, began to turn on the Jews again with a ferocity unequalled by his aristocratic enemies, there came the 1 a.m. knock on the door. Pavlov’s grandfather, who looked a little like Trotsky, was away addressing a meeting of railway workers; but his wife was at home and they took her away to one of the camps which history has always provided for Jews and she died giving birth to Leonid Pavlov.

There is my motive, Viktor Pavlov thought. The origins of my hatred. More often than not, he believed it.

* * *

He was born in violence during the siege of Leningrad in World War II, the son of a teenager, Leonid Pavlov, and a peasant woman, possibly wholly Jewish, possibly not, who had found time in between dodging shells and eating stews made of potato peelings and dog meat, to make love and get married. She was killed by a German shell shortly after giving birth to Viktor.

So many records were destroyed during the siege that it was easy to register Viktor as a Russian. This grovelling hypocrisy angered him in his teens, but later it was to become his strength.

When he was ten Viktor Pavlov stopped some bullies beating up a small boy with springy black hair, rimless glasses and a dark complexion, in the school playground in Moscow.

“Why,” he demanded, grabbing the arm of the biggest bully, “are you picking on him?”

The bully, whose name was Ivanov, was astonished. “Why? Because he’s a Yid, of course.”

“So what?” Pavlov was an athletic boy with flints in his fists which commanded respect.

“So what? Where have you been? Everyone knows about the Jews – it’s in the papers. They’ve just closed the synagogue down the road. It was the centre of the black market in gold roubles and Israeli spies.”

“I didn’t know you read the papers,” Pavlov remarked. “I didn’t know you could read.”

A crowd had gathered round the two protagonists on the sunlit, asphalt playground. The original victim had vanished.

Ivanov, who had a pudding face and pale hair cut in a fringe, ignored the question. “My father’s told me about the Yids. He was in the war.…”

“So was mine.”

“He said the Jews wouldn’t fight. He says we should finish off the job Hitler started.”

“Then your father’s an idiot. I was born in Leningrad. The Jews fought well. And what about the Jewish generals?”

Dodging logic, Ivanov searched for a diversion. He stared closely at Pavlov’s intense dark features, his cap of black hair, his hawkish nose; he saw intelligence and good looks and it made him mad. “Are you a Yid?” he asked. “Are you Abrashka?”

The crowd of boys was silent. The question was a provocation, an insult; although they weren’t sure why. Why was an evrei, so different from a Kazakh, a Kirghiz, a Uzbek?

Ivanov grinned. “Prove it.”

A cold, dark anger froze inside Pavlov, like no anger he had experienced before. He wanted to batter Ivanov into insensibility; to kill him. “I’ll prove it” – he put up his fists – “with these.”

Ivanov was still trying to grin. “That’s not proof.”

“What proof do you want?”

“Show us your cock.”

Recently, there had been a scandal in the suburb about Levin the circumciser. He had performed the small operation on the penis of a baby and then gone to Leningrad for a couple of days. But there had been sepsis, so the baby’s parents took the baby to a clinic where a Jewish doctor dressed the cut and told the parents they needn’t worry. But a porter reported the case to the police.

Three weeks later, after intensive interrogation, Levin made a public address renouncing his profession. It was, he announced in a beaten voice, a barbaric ritual. He appealed to Jews all over the Soviet Union to abandon it.

Pavlov advanced on Ivanov. Ivanov backed away appealing to the others: “I bet he’s been cut.” A few sniggered, the rest remained silent because there was ugliness here they couldn’t comprehend.

Pavlov hit him first with his left, then with his right, dislodging a tooth. Ivanov fought back strongly but he couldn’t match the inexorable determination of his opponent, his controlled ferocity. He got home blows in the face and stomach but they had no visible effect on Pavlov who kept coming at him. Pavlov bloodied Ivanov’s nose, closed one eye, buckled him with a punch in the solar plexus. Ivanov went down and stayed down whimpering.

Pavlov stood over him. “So you want to see my cock? Then you shall see it and lie there while I piss all over you.”

Pavlov unbuttoned his fly and took out his penis, foreskin intact. But he was saved from degrading himself by the appearance of a teacher. He buttoned himself up, standing defiantly beside his fallen opponent.

They were both punished for fighting but no reference was made to the reason for the fight. The teacher seemed to understand Ivanov’s attitude; likewise he understood Pavlov’s reaction to the suggestion that he might be a Jew.

This was Pavlov’s private shame: that he had taken the suggestion as an insult. He resolved to find out more about his mongrel heritage and asked his father: “Am I a Russian or a Jew?”

They were sitting in the small wooden house in the eastern suburbs of Moscow drinking borsch soup, mauve and curdled with dollops of cream, and black bread, which Viktor rolled into pellets. His father, although still a young man, was almost a recluse, hiding his Jewishness, earning a meagre living doing odd jobs and keeping his nose clean. Although in his death throes, Stalin was still on the ram-page.

His father stopped drinking his soup. “Why do you ask?”

Viktor told him what had happened in the playground.

His father looked worried. “Why fight about a thing like that?”

“I don’t know. Why should I be so angry because he suggested I was a Jew?”

His father leaned across the table, prodding the air with his spoon. “Listen, boy, you are a Soviet citizen. You are registered as one. I am a Soviet citizen, too. Forget anything you may know about your ancestors.” He paused. “About your mother even. This is a great country, perhaps the most powerful country in the world. Be proud to belong to it. Don’t sacrifice your life for the sake of the martyrs.”

Looking at his father’s wasted features, Viktor knew that, although he spoke truths, he lied. Subsequently he wondered if the decision to fight for Zionism was made then. Out of perversity, out of contempt – not fully realised at the time – for paternal weakness; out of his own shame.

From the boy he had protected in the playground he learned about Israel. It was once called Palestine and it was populated by people who had come from Egypt thousands of years ago. They read the Bible, worshipped their own God, their land was destroyed by the Romans and they spread all over the world. With them they took their traditions, their Bible, their customs, their diets, their suffering. Throughout history, the boy told his saviour, the Jews had been persecuted and in the holocaust they had been slaughtered by the million by the Nazis.

Viktor envied the boy his birthright; but he couldn’t understand his acceptance of his plight.

Pavlov’s Jewishness continued to bother him in his early teens; but it was still only a needle, not the knife it was to become. There were summer camps and sports and girls to distract him; he was emerging as a scholar with a keen mathematical brain and the school had high hopes for him at university.

It wasn’t till he reached the age when young men seek a cause – when, that is, he became a student – that Viktor Pavlov took the first steps that were to lead him on the path to high treason in the year 1973.

* * *

He was nineteen and sleeping with a passionate Jewish girl, a little older than himself, in the Black Sea resort of Sochi. He was at a Komsomol summer camp, she was staying in one of the town’s 650 sanatoriums. Her passion and expertise gave him much pleasure; but her fervour had a long-term quality to it and he expected trouble if he broke up the affair, from her brother, a wiry young man with a lot of muscle adhering to his prominent bones, the face of a fanatic and a premature bald patch which looked like a skull-cap.

One sleepy afternoon, with the sun throwing shoals of light on to the blue sea, Viktor and the girl, Olga Soliman, walked up the mountain road to Dagomys, the capital of Russian tea, 20 kilometres from Sochi. They drank tea on the porch of a log cabin, ate Kuban pies, then headed for the woods. Their love-making had a heightened lust to it on a bed of pine-needles with the sun casting leopard-spots of warmth on their bodies. Such was the aphrodisiac quality of the open air, the sun, the pinewoods, that Viktor was quicker than usual. But, anticipating him, so was Olga.

She pointed at his sex shrinking inside its little fleshy hood. “I shouldn’t let you touch me with that,” she said. “Why don’t you have it cut off?”

It was a joke and Viktor laughed. But it was also the truth and a part of him hated the joke.

“Too late now,” he said. “Perhaps I should have the whole thing cut off.”

She nuzzled him, biting his ear. Her skirt was around her waist and her big, brown-nippled breasts were still free. She said: “Don’t ever do that. I’ve got a lot of use for that.” In the long years to come, she implied. And yet, Pavlov thought, with the sun dappling his skin, and the smell of her in his nostrils, I love her. Knowing at the same time that he didn’t, not in the absolute, permanent sense. Love was an emotion he could control. He wasn’t so sure about hate.

Arm in arm, they walked down the mountain road to Sochi where, it was claimed, the mineral waters of Matsesta could help patients suffering from heart diseases, neuroses, hypertension, skin diseases and gynaecological disorders. There wasn’t much that Sochi couldn’t alleviate and the brochures asserted that 95 per cent of all those seeking treatment left the resort considerably improved or cured. But Viktor Pavlov wasn’t among them. His disease went back centuries and no one had ever touched upon a cure.

When they arrived at the Kavkazskaya Riviera sanatorium which took Intourist guests and was therefore prestigious, Olga’s brother, Lev, was waiting for them.

He looked at Viktor with fraternal menace. “Had a good time?” Olga’s parents were also staying at the sanatorium and the view was that Viktor Pavlov was already one of the family and should make it legal.

“Pleasant,” Olga said. “But exhausting.” Allowing the implication to sink home before adding: “It was a long walk.” She smiled contentedly – possessively, Viktor Pavlov thought.

They were standing in the lobby of the sanatorium, breathing cool, remedial air.

Lev said: “I have bad news for you.” He held a long mantilla envelope with the words Moscow University on it.

Olga took the envelope. “Why bad news?”

Lev Soliman grimaced. “Is it ever any other?”

They were all three at the University studying different subjects.

“You’re a pessimist,” Olga told her brother.

“I am a realist.”

“To hell with your realism.”

But her fingers shook as she ripped open the envelope with one decadent, pink-varnished fingernail.

She read the letter slowly. Then she began to shiver.

“What is it?” Viktor asked.

“What’s the good news?” her brother asked.

She re-folded the letter, replacing it in the envelope. “I’ve been expelled from the university,” she said.

They were silent for a moment. Then Viktor demanded: “Why?” He paused because he knew the answer. “You were doing well … your examination marks were good.”

Lev Soliman turned on him. “Don’t pretend you don’t know. Don’t be too much of a hypocrite, a half-caste. She has been expelled because she is a Jew.”

* * *

When they returned to Moscow, Viktor Pavlov told Lev Soliman that he thought he should quit university.

They were walking through Gorky Park, filled this late-summer day, with guitar-strumming youths, picknicking families, lovers, union soldiers and sailors. Bands played, rowing boats patrolled the mossy waters of the lake, the ferris wheel took shrieking girls to heaven and back again.

“Why?” Lev asked. “Your guilt again?”

“Perhaps.” They stopped at a stall near a small theatre and bought glasses of fizzy cherry cordial. They were close now, these two, close enough to exchange insults without malice. “I feel like a traitor.”

“Don’t,” Lev Soliman said. “Feel like a hero.”

“What the hell are you talking about?”

“I’ll tell you.” Lev pointed at the ferris wheel. “Let’s take a ride. No one can overhear us up there. Not even the K.G.B.”

The wheel stopped when they were at its zenith and they looked down on Moscow glazed with heat; the gold cupolas of discarded religions, the drowsy river, the fingers of new apartment blocks. Lev Soliman pointed down at the pygmy people in the park. “Good people,” he said. “A great country. Make no mistake about that.”

“I don’t,” Viktor told him. “I was born in Leningrad. Any country that can come back after losing twenty million is a great country. But not so great if you’re a Jew, eh?”

“But you’re not.”

A breeze sighed in the wheel’s struts; the car perched in space, swayed slightly.

Pavlov said: “I am a Jew.”

“That’s not what it says on your papers.”

“You can’t blame me for that. There are thousands of Jews registered as Soviet citizens through mixed marriages.”

Lev shrugged. “Maybe. But you’re a more convincing case. All your family records destroyed in Leningrad. Perhaps your mother was pure Russian.”

“She was a Jewess.”

“That’s not what your father told the authorities. And he’s registered as a Soviet citizen, too. So you see, your case is pretty clear-cut.”

Viktor twisted round angrily, making the car lurch. “What are you getting at?”

“Simply this.” Instinctively Lev looked around for eavesdroppers; but there were only the birds. “You can be far more useful to the movement than anyone with Jew stamped on his passport.” He gripped Viktor’s arm. “There is a movement within the movement. That’s where you belong.”

* * *

One month later Lev Soliman was expelled from the University. His one-room apartment was searched under Article 64 – “betrayal of the Motherland”. He was taken to the Big House and interrogated. A fortnight later he was transferred to a mental institution. Viktor saw him once more two years later; by that time he was insane.

* * *

Lev Soliman left Viktor Pavlov with the embryo of an underground movement that had its origins in April, 1942, when the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee of the Soviet Union (JAC) was founded. In those days the Russians needed the Jews to help fight the Nazis and to spread propaganda to the four corners of the world to which the Diaspora had taken them.