Полная версия

The Stonehenge Letters

The distasteful nature of Sofie’s demands left Sohlman puzzled as to how a man as sophisticated as Nobel could have fallen in love with such an ill-suited woman. One explanation for Nobel’s puzzling infatuation with Sofie relates to his fragile psychological state at the time of their initial meeting. A few months prior to encountering Sofie, Nobel had taken out the Victorian equivalent of a classified advertisement in a Viennese newspaper: ‘A wealthy and highly educated old gentleman living in Paris seeks to engage a mature lady with language proficiency as secretary and housekeeper’. The successful applicant was a thirty-three-year-old Austrian woman, Countess Bertha Kinsky von Chinic und Tettau. The aristocratic title was misleading. Bertha was a poor cousin within an otherwise prominent family and was then working as a governess in the home of the wealthy Baron Karl von Suttner. After travelling by train to Paris, Bertha was met by Nobel, who then escorted his new employee to comfortable quarters in a nearby hotel. Nobel appears to have fallen instantly in love. By all accounts, Bertha was beautiful and sophisticated. She was fluent in four languages. She shared Nobel’s love of literature and opera.fn17 She, in turn, appears to have been pleasantly surprised by her new circumstances: ‘Alfred Nobel made a very good impression on me. He was certainly anything but the “old gentleman” described in the advertisement.’

Unknown to Nobel, Bertha arrived in Paris still deeply attached to Arthur Gundaccar von Suttner, the son of her recent employer and seven years younger than herself. After only one week of employment, Bertha returned to Vienna so that she and Arthur could elope. Nobel was heartbroken. Despite their limited acquaintance, he had already indulged in fantasies about their life together, including the renovations that would be required to accommodate a married couple within his elegant Parisian mansion on Avenue Malakoff. Reeling from the pain of unrequited love,fn18 Nobel retreated to a spa in Austria. It was there that he met Sofie and her easily won affection.

Figure 10. Bertha von Suttner.

Sohlman, not completely naive, eventually concluded that Sofie represented more than a timely remedy for Nobel’s injured self-esteem. There was also the matter of Nobel’s more ‘basic’

needs. In Sohlman’s words, Sofie was adeptly prepared to do ‘everything possible to amuse and entertain him’.

Years later, Nobel would again find himself in the lingering lonely aftermath of a failed relationship, this time with Sofie as the rejecting figure. Once again, Nobel would turn to a younger woman for affection.

CHAPTER 5

STONEHENGE FOR SALE

Among Nobel’s personal papers was a series of letters involving a correspondent by the name of Florence Antrobus. It was a forename and surname that Sohlman immediately recognised. In late January 1894, Sohlman had accompanied Nobel on a brief trip to London. Nobel had been scheduled to appear before the House of Lords, then England’s highest court, as a plaintiff in the so-called Cordite Case. The proceedings were the legal culmination of a bitter dispute that arose from Nobel’s invention of a smokeless explosive powder that he had patented in 1877 as ballistite. In 1899, two British scientists (who had been former associates of Nobel) proceeded with their own patent for a compound, which they named cordite. As cordite was virtually identical to ballistite, Nobel was suing for patent infringement.fn19

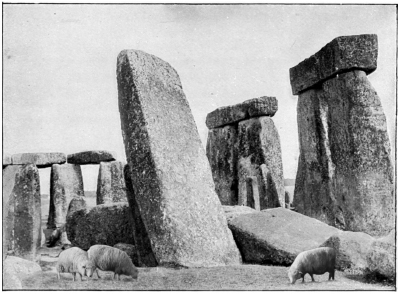

After completing two days of testimony in London, Nobel asked Sohlman to join him on a short excursion. Until then, Sohlman had been unaware that Nobel was actively looking to procure a substantial tract of land in England in order to test cannons, missiles, and other large-scale armaments. With some excitement, Nobel had read of an interesting opportunity on the Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, about eighty-five miles from London. It was the headline in London’s Evening News that had captured Nobel’s attention: ‘Stonehenge for sale!’ Although the majestic stone ruins were highlighted in the accompanying advertisement, Nobel had also noticed that 1,300 acres of adjoining land would be associated with the purchase. As Nobel had yet to establish a foothold in the English explosives industry, he was intent on inspecting the acreage for sale as soon as possible.

Nobel and Sohlman visited the property in early February 1894. Acting as principal host and guide was Sir Edmund Antrobus, Third Baronet of Antrobus and proprietor of the estate.fn20 The baronet was a ‘motivated’ seller. Although proud to preside over what those in the Antrobus family referred to as the ‘great relic’, the associated responsibilities had become tedious. Of primary concern was the onslaught of visitors, many of whom were intent on removing stones as souvenirs or desecrating those still remaining. There were other frustrations. Unstable stones had to be propped up with scaffolding; horse manure was everywhere; the burrows of rabbits and rodents were literally undermining the monument’s safety; and the baronet increasingly resented the incessant and often patronising requests from those who wished to explore and excavate the site, all of which he refused.

The additional sad reality was that the baronet needed money. Despite the illusion of wealth, he was badly in debt due to a combination of poor investments and the need to maintain ‘appearances’, which for the baronet meant a large servant staff and a far-too-lavish home. The latter was Amesbury Abbey, located some two miles from Stonehenge in the village of Amesbury. The baronet had spent his inheritance building the three-storey mansion with its imposing loggia on the site of the original abbey that had been destroyed by fire. At the time of Nobel’s visit, the sizeable residence was then home to nine servants in addition to the baronet, his wife, and an assortment of near and distant relations.

Once pleasantries had been exchanged with the baronet, the inspection proceeded. Despite the frailty of his sixty years and the chilly February weather, Nobel successfully utilised various vantage points and a commandeered horse-driven carriage to survey a great deal of the property. Nobel’s opinion was favourable: though he shielded his impressions from the baronet, he immediately recognised that the countryside surrounding Stonehenge would serve as an ideal artillery range. The appraisal ended at the ‘great relic’ itself. There, the baronet had prearranged the presence and assistance of his daughter-in-law Florence, who was among those family members who lived at Amesbury Abbey.

Florence was an unusually gifted and intelligent woman. Her wealthy father had died by suicide when she was seven, leaving her mother, Georgina, to raise her and two younger sisters. Thanks to Georgina’s progressive attitude and an extensive trust fund that afforded the best tutors, Florence’s education included not only the ‘domestic’ pursuits and English poetry and prose, a typical curriculum for a woman of her time, but also subjects such as mathematics and science, which were then largely reserved for males of her generation. Much to Georgina’s pleasure, Florence excelled at her studies and was to be one of the first female graduates of Bedford College at the University of London. It was there that Florence met the baronet’s eldest son (also named Edmund) and, after a courtship unusually extended due to Edmund’s military service in the Sudan, the couple married in 1886. Florence had then set aside her aspirations to teach English literature and settled, a little uncomfortably, into a traditional Victorian marriage.

At the time of Nobel’s visit, Florence’s husband was still active in the Grenadier Guards, and was stationed in London as Brevet Colonel of the Third Battalion. The couple’s only child, then seven, was also in London as a boarding student at a boys’ preparatory school.fn21 Despite such separations from her husband and son, Florence was content living in Amesbury. She had developed a profound connection to the countryside, and often walked to Stonehenge to admire the old stones. There, she would spend hours sketching, in her words, their ‘dark, mysterious forms’ at different hours of the day or, in a series of notebooks, writing the poems that the ‘magic of Stonehenge’ had inspired.

At the baronet’s request, Florence carefully escorted Nobel and Sohlman between the upright and fallen stones, sharing her knowledge of Stonehenge as they proceeded. She particularly wanted Nobel and Sohlman to appreciate the beauty of their surroundings, and described in great detail how the stones changed their colours with the shifting weather. Florence also provided a charming overview of the various theories addressing how Stonehenge had arisen. The earliest of these was a medieval legend that implicated the conjurations of Merlin the Magician. Subsequent ‘experts’ ascribed Stonehenge to the work of invading armies, most often the Romans or the Danes. According to Florence, the most popular current belief was that the Druids, the most prominent priests of ancient Britain, had erected Stonehenge as a temple. Pointing dramatically to a large flat stone lying on the ground, Florence ended the walkabout by announcing in a hushed voice, ‘it was upon this very Slaughter Stone that the Druids practised their ritual of human sacrifice’. Taking Nobel by the hand to steady his stride, Florence then cheerily provided her own caveat emptor: she herself was uncertain if any of the explanations were true and preferred simply to delight in the splendour and mystery of Stonehenge.

Nobel was captivated by Florence’s performance (or, as Sohlman would later assert, by Florence herself). After posing a number of questions related to whether the missing stones might have been deliberately demolished and, if so, how, Nobel then insisted on briskly climbing the wooden scaffolding supporting the tallest of the upright stones. The elevation afforded Nobel a splendid view of the adjoining acreage as well as the nearby River Avon.fn22

As Nobel thanked Florence, he surprised her by quoting from Lord Byron’s epic poem Don Juan, ‘The Druids’ groves are gone – so much the better’. Just as unexpectedly, Florence quickly finished the couplet, ‘Stone-Henge is not – but what the devil is it?’ To their delight, the two quickly discovered that each loved the English Romantic poets, Byron best of all. Sohlman was astonished. He had no idea that Nobel had read and memorised a great deal of poetry during his adolescence in St Petersburg. Moreover, when Florence shyly confided that she was also attempting to convey ‘feebly in words’ her poetic impressions of Stonehenge, Nobel shared that he, too,

had once written poetry as a young man. Unlike his own failed literary aspirations, however, Nobel assured Florence that he was certain it would one day be his pleasure to read her verse in print.

On returning to the continent, Nobel offered to purchase Stonehenge and the advertised acreage. Serious negotiations continued by both letter and telegram over the next few weeks. In dispute was the issue of grazing rights, which the baronet had hoped to maintain. Nobel was amused. Unless the baronet secretly intended to establish an outdoor abattoir, the presence of browsing sheep was dangerously incompatible with Nobel’s own intention of using the property as an oversized firing range. Though the baronet would concede this point, there was still the matter of establishing an agreed upon purchase price. The baronet was demanding £125,000. Given that downland was then worth only £10 per acre, it meant the ancient monument itself was being valued at over £100,000, a price Nobel viewed as highly inflated. Nevertheless, as Nobel had found himself strangely attracted to the presence of the old stones,fn23 his counter-offer was a still generous £90,000. The difference, however, would soon become a moot point.

Within days of his visit, rumours had reached Westminster that Nobel was about to acquire Stonehenge. Unfortunately for Nobel, there was now mounting concern throughout the United Kingdom that wealthy foreigners were seeking to buy structures of national importance just to dismantle them, either for the worth of their components or in order to transport and re-erect them upon foreign soil. The precipitant for such apprehension was the recent sale of Tattershall Castle in Lincolnshire. A consortium of American entrepreneurs had purchased the castle, only to remove its twenty-eight medieval stone fireplaces for immediate sale across the Atlantic. Members of Parliament and peers of the House of Lords, previously more concerned with the property rights of private citizens, were finally recognising the importance of preserving England’s historic monuments and properties. With the sale of Stonehenge to Nobel apparently on the horizon, and with no certainty of Nobel’s intentions, the British politicians acted quickly.

Figure 11. Stonehenge.

In early March 1894, the Parliament of the United Kingdom introduced the Ancient Monuments Protection Act. Although the Act was designed principally to preclude the injury or defacement of historic buildings and monuments, there was an additional caveat: the owner of any ‘ancient monument’ scheduled in the Act was no longer permitted to sell or gift the monument of interest to anyone other than a citizen or agency of the United Kingdom. Prominent on the list of sixty-eight prehistoric monuments mentioned specifically in the Act was ‘the group of stones known as Stonehenge, Amesbury, Wiltshire’.

Nobel was indignant. Though he had assured the baronet he had no intention of razing Stonehenge, he was well aware of the Act’s ramifications. Despite both men’s disappointment, there was little choice but to amicably end the negotiations.

Florence’s first letter to Nobel was dated two months later.

CHAPTER 6

FLORENCE ANTROBUS

Amesbury Abbey

3 May 1894

Dear Mr Nobel,

I do hope you remember our meeting. I had the recent pleasure of introducing you to the grandeur of Stonehenge, those magnificent stones just beyond our Amesbury home. I confess I was pleased to hear that you are no longer their suitor, but not because you would be their unworthy guardian. No – it is only because I would miss the old stones so desperately, though they no longer stand as proud as they once did in ancient days.

I trust you do not think it overfamiliar of me to mention that I still recall with delight our spirited discussion – not only of Stonehenge but of Shelley, and Wordsworth and, of course, our dear Lord Byron.

Mr Nobel: when you departed, you encouraged my literary pursuits, fanciful as they may be, and I turn to you now for advice. Would you see fit to share your thoughts on the enclosed verse and prose? If so, you will find I have attempted to express my profound sentiments for the poetical aspects of Stonehenge. I hope I am not overstepping propriety by making this request, but I sensed in you a shared love of the written word – and I hope of Stonehenge itself.

Regardless of your interest in my minor ambitions, I do trust I can write to you from time to time. I am concerned about your health and encourage you to dress more warmly when outside.

Sincerely,

Florence C. M. Antrobus

P.S. Since your visit, the baronet has received no other offers for Stonehenge. Indeed, the Inspector of Ancient Monuments fn24 has recently arrived – unannounced! – and has now presented the baronet with a ‘Preservation Order’. A number of stones must immediately be made safe, at the baronet’s expense, and the roadway for wheeled traffic that runs through the monument must be diverted. It is apparently now our legal ‘duty’ to preserve Stonehenge. The baronet is furious; he is convinced the ongoing costs of upkeep will now jeopardise any chance of selling Stonehenge. I am, on the other hand, enormously happy!

Nobel was relieved. The vast majority of the correspondence he received was what he would refer to as ‘begging letters’ – individuals in difficult personal circumstances, funding campaigns to raise statues, and so on. It was therefore with genuine pleasure and interest that Nobel read Florence’s letter and the enclosures it contained: a small packet of poems, six in all, and a short piece of pastoral prose detailing the sun’s passage through the stones.

Nobel’s letter of response, written in English, arrived in mid-July, just over two months later.

San Remo

15 July 1894

Dear Miss fn25 Antrobus,

I most certainly remember our meeting at Stonehenge. Your charming tour made a great impression upon me and my thoughts have returned on more than one occasion to the delightful time we spent together. I was fortunate indeed to have such a well-informed guide.

And now to receive your wonderful poetry and prose. Thank you for entrusting me with it. I am far from a worthy critic, but I read all you enclosed with interest and admiration. I must again encourage you to publish your work one day. Your talents must not be wasted only on me!

And now a request of you. Though I first regretted my failure to acquire Stonehenge, I am now relieved I have not deprived you of your muse. However I believe the Inspector is correct; it was also my impression that the taller stones are in imminent danger of falling. Would you and your family do me the honour of accepting a contribution towards the costs incurred by the ‘Preservation Order’? As I wish to see the stones again one day – and their gracious docent – it is in MY selfish interest that this offer be accepted.

My warmest greetings to your husband and the Baronet. I remain,

A. Nobel

Florence replied immediately, thanking Nobel for his generous words. She hoped, of course, that Nobel would indeed visit again, perhaps in the fall, when he might experience ‘the wild, tempestuous autumnal gales that usually sweep across the Plain in October’. She was firm, however, on declining any financial support for Stonehenge. As she conveyed to Nobel, the baronet, a proud man, would simply hear of no such assistance.

Although they would not, in fact, meet again, Florence continued to write to Nobel at regular intervals. In between descriptions of life at Amesbury Abbey, there began to appear more personal asides, including a diffident sharing of her husband’s prolonged absences and the growing burden of her loneliness. Most often, however, Florence wrote about Stonehenge. Emboldened by Nobel’s praise, she soon divulged that she had decided to write a ‘sentimental’ guide to Stonehenge, one that she hoped a traveller to Stonehenge might find ‘pleasure in reading’. It would contain her ‘poetical and picturesque’ impressions of Stonehenge, such as found in the following letter:

Amesbury Abbey

3 April 1895

Dear Mr Alfred Nobel,

Late this morning I walked to Stonehenge. Though I have visited the exquisitely-coloured stones a thousand times before, I have never failed to be moved by their startling, sudden presence. For even from the banks of the nearby River Avon, the old stones are at first nowhere to be seen. Yet as one moves determinedly through the crackling grass and up the winding valley with the turquoise spring flowers signalling the traveller’s way, the tallest of the stones suddenly appear! Those nearest join together in a large outer circle – as if each was holding another’s hands – and together the ancient stones stand in defiant solidarity against the onslaught of time.

I stayed until evening. The sense of peace and tranquillity are with me still.

Ever sincerely,

Florence Antrobus

Though not as prolific a correspondent as Florence, Nobel’s responses were always courteous and gracious. He was genuinely admiring of Florence’s ‘poetical’ powers of observation. But Nobel’s intrinsic inquisitiveness and pragmatism also led to more prosaic questions.

Björkborn Manor

13 July 1895

Dear Florence, (I trust I may name you so?)

Thank you for your recent letters. It is particularly exciting to hear news of your intention to publish a ‘sentimental’ guide to Stonehenge. I can think of no better wordsmith to capture the varying moods and colours of the ‘great relic’. But might your ‘sentimental’ guide also be a ‘practical’ one – a compilation of the facts and considerations of learned authorities on the subject of Stonehenge? From where did the stones arise? What purpose lay behind this ancient structure? Who were the people who built these circles? I still recall with pleasure your entertaining account of such matters during my visit to Stonehenge. Might you now explore these questions in a more methodical and scholarly way? It is my view that true knowledge emerges only by careful and detached study, preferably by examining the words and works of those who are cleverer than one self.

But no more preaching! I have news that may interest you. I am now settled at Björkborn Manor and have shared your interest in Stonehenge with the local antiquarians. It appears there is a place in southern Sweden where many larger boulders also stand – but in the shape of an ancient ship. It is known as the Ales Stenar.

Perhaps one day I will have the pleasure of providing you with a tour of our country’s Stonehenge?

Sincerely,

A. N.

P.S. Please accept my gift of a Remington typewriter. It is a selfish gesture on my part as I take such delight in reading your tidings of Stonehenge.

Florence was pleased to learn of Ales Stenar. She was even more delighted to receive the typewriter. Taking Nobel’s suggestions seriously, she began to gather and read all existing accounts that touched upon Stonehenge, forwarding to Nobel facts of particular interest. In response, Nobel’s next gift was a camera.fn26 He was now encouraging Florence to document the general appearance of Stonehenge, not only by providing descriptions of the individual stones, but by including relevant illustrations and photographs. In thanking Nobel, Florence included not only photographs of Stonehenge but also a keepsake of her own likeness.

Nobel was, of course, deeply touched by Florence’s personal photo and her appreciation. However, it would be some time before he would write again. After the summer at Björkborn Manor, Nobel had travelled south to Paris. That fall, he began to experience bouts of severe chest pain. Nobel was hospitalised against his protestations and then spent two months confined to his Paris mansion. It was a contemplative Nobel who wrote Florence from Paris in November 1895.

Figure 12. Florence Antrobus.