Полная версия

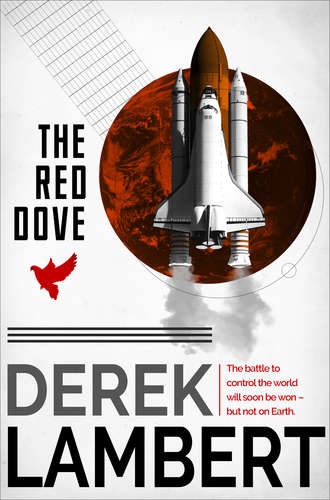

The Red Dove

An audio-visual surveillance operation had been mounted on a group of foreign businessmen visiting the fleshpots of Los Angeles, San Francisco and Las Vegas. Sex, drugs, gambling, alcoholic intake – every peccadillo had been photographed and recorded. All well and good except that (1) the operation had been blown and (2) the foreigners were Arabs.

With the result that the Arab government in question was now threatening to cut off oil supplies to the United States because of a ‘gross impertinence’ authorised personally by none other than George Reynolds, Director of the CIA.

Not that they would because the tide of oil was beginning to turn against Arab domination of the market. Nevertheless, America had been put in an embarrassing position, which was a windfall for the lemming-like critics of the CIA. Reynolds had no doubts about the wisdom of authorising the surveillance – the Washington-based Arabs had been engaged in espionage – and his only regret concerned the foul-up his agents had made of it.

But to survive he needed a coup that would dwarf the Arab misadventure into insignificance.

He needed a spectacular.

It was at times like this, he thought as he turned restlessly in the bed, that you needed someone beside you. Someone to bring warmth to icy calculation. Someone to share.

But at least I’ve been honest with myself, he thought as dawn began to creep into the bedroom.

The two computer print-outs were flown from Washington to Los Angeles within six hours of Reynolds’ call and brought by automobile along Coastal Highway 101 to the ranch.

The first was a routine assessment; the second and more interesting document was the result of an intensive and prolonged exchange between operator and computer.

The assessment was based on the investigation Reynolds had authorised on Nicolay Talin in August 1971, which had been revised annually.

Reynolds read the assessment first, sitting in the sunlit bedroom; from outside he could hear the lowing of cattle.

NICOLAY LEONID TALIN.

BORN 10 OCT. 1950, NEAR KHABAROVSK, EASTERN SIBERIA.

ATTENDED WORK—POLYTECHNICAL SCHOOL 14 AT AGE 7 (NORMAL SCHOOL STARTING AGE IN SU). BY GRADE 2 SINGLED OUT AS POSSESSING EXCEPTIONAL ACADEMIC POTENTIAL.

AT AGE SEVEN JOINED LITTLE OCTOBRISTS, AT AGE NINE YOUNG PIONEERS. GROUP LEADER REPORTED TO PARTY COMMITTEE THAT TALIN WAS BOTH HIGHLY INTELLIGENT AND QUOTE UNUSUALLY ADVENTUROUS UNQUOTE. LATTER POSSIBLE EUPHEMISM FOR EARLY SYMPTOMS OF REBELLION.

EMOTIONALLY AFFECTED AT AGE 12 BY DEATH OF FATHER THROUGH RADIATION SICKNESS CONTRACTED IN COBALT MINE NEAR YAKUTSK REPUTEDLY COLDEST PLACE ON EARTH. MOVED WITH MOTHER TO NOVOSIBIRSK AND ENTERED FOR ELITE PHYS-MAT SCHOOL NO. 5.

The climatic observation, Reynolds reflected, pin-pointed the fallibility of computers: the feed-in. The operator, probably working on a sweltering day in Washington, had been unable to resist this totally irrelevant morsel of information about Yakutsk.

AT SCHOOL SCHOLASTIC ABILITIES CONFIRMED AS OUTSTANDING. EARLY COMPUTER ASSESSMENT CHANNELLED POTENTIAL TOWARDS AVIATION. THIS SUBSEQUENTLY AMENDED TO AEROSPACE. PLACE RESERVED MOSCOW STATE UNIVERSITY.

Early computer! As if the sophisticated brain machine spewing out Talin’s life was sneering.

CAREER ENDANGERED BY OUTBREAKS OF DEFIANCE DURING YOUNG PIONEER INDOCTRINATION INTO PARTY DOGMA, LENINISM ETCETERA. SAVED BY SYSTEM SO RIGID THAT, HAVING FILED SUBJECT AS FUTURE HERO, IT COULD NOT QUESTION ITS OWN JUDGEMENT.

SYSTEM CONCENTRATED ON WIDOWED MOTHER, BRIBED THROUGH USUAL CHANNELS AVAILABLE TO SOVIET ELITE, TO REASON WITH SON. PLOY LARGELY BUT TEMPORARILY BRACKET SEE LATER UNBRACKET SUCCESSFUL.

Why the hell did this computer write commas but not brackets and quotes?

AT AGE 16 JOINED KOMSOMOL BRACKET YOUNG COMMUNIST LEAGUE UNBRACKET. LATER DEPARTED NOVOSIBIRSK FOR MOSCOW. AT UNIVERSITY AND DURING KOMSOMOL ACTIVITIES REBELLIOUS SPIRIT AGAIN NOTICED. IN CONVERSATION REPEATED DOUBTS EXPRESSED BY YOUNG PEOPLE IN ’50s FOLLOWING KRUSHCHEV’S DENUNCIATION OF STALIN AT TWENTIETH PARTY CONGRESS.

Put an S in front of Talin’s name, Reynolds thought, and there was Stalin.

APPROACH MADE AT THIS STAGE BY OLEG SEDOV COSMONAUT AND OPERATIVE OF SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL DIRECTORATE OF FIRST CHIEF DIRECTORATE OF KGB WORKING IN CONJUNCTION WITH DOSAAF RESPONSIBLE FOR INDOCTRINATION OF YOUTH BEFORE MILITARY SERVICE.

UNDER INFLUENCE OF SEDOV MARKED CHANGE NOTED IN OUTWARD ATTITUDE OF TALIN. RELATIONSHIP SEEMS TO HAVE PROGRESSED BEYOND MENTOR-PUPIL NORM. POSSIBILITY OF HOMOSEXUAL TENDENCIES INVESTIGATED BUT REJECTED IN RELATION TO TALIN ON GROUNDS OF HIS UNDOUBTED HETEROSEXUALITY.

FROM UNIVERSITY SUBJECT TRANSFERRED TO NEW YURI GAGARIN COSMONAUT TRAINING CENTRE AT STAR TOWN, ZVEDNY GORODOK, IN EASTERN SUBURBS OF MOSCOW. THERE TO TYURATAM, BETTER KNOWN IN WEST AS BAYKONUR COSMODROME, IN KAZAKHSTAN.

INTENSIVE TRAINING CONTINUED IN PREPARATION FOR SPACE SPECTACULAR….

Was Washington inhabited totally by movie buffs?

…INVOLVING SOYUZ AND SALYUT CRAFT. AT SAME TIME ROMANCE FIT FOR FUTURE HERO ARRANGED WITH DANCER AT BOLSHOI DESTINED TO BECOME PRIMA BALLERINA. LUCKILY FOR SOVIETS TALIN AND GIRL, SONYA BRAGINA, WHOLE-HEARTEDLY ENDORSED ARRANGEMENT PRESUMABLY ASSUMING IT HAD BEEN FORTUITOUS.

TALIN’S SPACE FLIGHT CONSUMMATELY SUCCESSFUL. SUBJECT ELEVATED INTO SOVIET ELITE COMPLETE WITH RED PASSBOOK. BECAME YOUNGEST HERO OF SOVIET UNION IN HISTORY. ACCOMPANIED BY OLEG SEDOV PILOTED FIRST SOVIET UNION SHUTTLE DOVE 1 IN MAY 1983.

CONCLUSION:

TALIN REPRESENTS POSSIBLE MATERIAL FOR MANIPULATION. BEHAVIOURAL PATTERN INDICATES CONTINUED EXISTENCE OF REPRESSED RECALCITRANCE. FACT THAT SUBJECT IS IDEALIST SUPPORTED BY EVIDENCE THAT SOVIETS HAVE NOT INVOLVED HIM IN AGGRESSIVE ASPECTS OF SPACE PROJECTS. PRINCIPAL OBSTACLE THAT WOULD HAVE TO BE OVERCOME – UNDOUBTED PATRIOTISM OF SUBJECT.

Reynolds called the kitchen and asked for coffee. Through the window he could see the President; he had abandoned his axe and was digging a posthole. Beside him stood his wife in jeans and shirt carrying a basket of flowers. Reynolds envied them their togetherness.

The cook brought the coffee. He drank it black and began to read the second print-out.

The document wasn’t as crisp as the Talin assessment. Questions and answers hadn’t yet been synthesised because Reynolds had emphasised that the priority was speed. But the direction of the conversation between man and machine was easy enough to follow.

Relentlessly, the operator had picked the computer’s brains to find an agent capable of subverting a young Hero of the Soviet Union. Into its electronic intelligence he had fed Talin’s age, background, environment, sexual inclinations, physical appearance, aerospace career details, ambitions, pastimes, IQ, character estimate …

The operator had then fed his machine with the specialised qualifications needed by the CIA agent. Knowledge of Russian, ability to mix – here the computer had been very much taken with the word simpatico – unswerving devotion to country, fatalistic attitude to death. …

The computer had then responded with the shattering conclusion – NO SUCH AGENT AVAILABLE.

Which was hardly surprising, Reynolds brooded. What sort of agent was it who would be able to travel undetected through the Soviet Union to Leninsk, known in Russia as Rocket City, where cosmonauts working at the Tyuratam space centre lived, and single-handedly persuade a Hero to defect?

But the operator hadn’t given up. The conversation between master and machine – or was it the other way round? – had continued.

Reynolds guessed where it was leading. He should have known all along. He stopped reading and opened an envelope marked PHOTOGRAPHS WITH CARE that had accompanied the print-outs.

There was Nicolay Talin descending the steps from Dove 1; thick blond hair brushed back in timeless style, keen features, slight cleft in the chin. Triumphant – and yet the eyes seemed to be searching for someone, something. A Viking, Reynolds thought. No, a Siberian.

He looked at the second photograph and came face to face with a man who had once briefly obsessed him. Had the mug shot been taken before or after that obsession? After. The experience had drawn lines from nose to mouth, pouched the eyes, changed the expression.

Nevertheless, there were still traces of youthful appeal in the face staring accusingly at him. The moustache that made him look like a cop, the aggressive features, the slant of the brown eyes that softened the aggression. Also discernible was the intellect that had earned him a summa cum laude BS in physics at Rice University, Houston. The casual observer might also suspect that the face in the photograph had been supported by an athlete’s body, and he would have been right – both the Dallas Cowboys and the Los Angeles Rams had tried to sign him as a quarterback only to discover that, for him, sport was only a diversion from his real purpose.

And that purpose had been to fly. First with the USAF, graduating to F–15 Eagles, but always viewing the Earth’s atmosphere as a step ladder to space. He had subsequently been selected for training with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and that selection had been a mistake.

Reynolds returned to the print-out, speed-reading because he knew the details and he didn’t enjoy them, returning finally to the abridged service biography.

MASSEY, ROBERT S. (B. 14 APRIL 1939). PILOT USAF. SELECTED NASA DEC. ’65. COMMAND MODULE PILOT FOR APOLLO MOON LANDING 1972. TRANSFERRED SHUTTLE EXPERIMENTS, DESTINED FOR FIRST TEST OF ORBITER 101 SHUTTLE IN 1977 BUT WITHDREW: DIVORCED. INACTIVE.

Inactive! A euphemism of the space age.

But it was all there in the extended print-out. Every requirement for the plan that had been evolving in Reynolds’ brain since the computer had told him to forget trying to find a trained agent. Right down to aerospace experience, right down to ‘fatalistic attitude to death’ …

Now all he had to do was persuade Massey. All? After what I did to him? Sometimes Reynolds wondered at his own icy optimism.

He locked the print-outs and photographs in his attaché case and left the room. Outside the President was leaning against a fence drinking root beer and talking to his wife.

Reynolds told him that he was leaving. ‘But I’ll be back for dinner Saturday,’ he said.

‘That’s fine, George,’ the President said. ‘Just fine.’ He picked up his axe.

In Moscow that day it was even hotter than in California.

But, unlike capital cities such as Washington and London, Moscow wasn’t adversely affected by the heat; here summer was a luxury and a sweltering day encouraged energy rather than torpor.

Sightseers thronged the Kremlin grounds; ice-cream and kvas sellers sold their wares as chirpily as Cockney barrowboys selling hot chestnuts in winter; on the packed beaches on the outskirts of the city bathers swam energetically to the rhythms of ping-pong balls traversing the nets on the promenade tables; in Gorky Park love blossomed feverishly while young men in black-market jeans strummed their guitars.

In a walled garden near the memorial erected to mark the line where the Russians halted the German advance on Moscow in World War II, the heat collected like soup. But despite their age, despite their infirmities – one had been fitted with a pacemaker, the other with a steel plate in his skull – the two men in open-neck white shirts playing chess in the shade of a birch tree displayed no discomfort because that would have been an admission of frailty.

The garden, clotted with blooms trying to beat the axe of the executioner winter, was attached to a dacha belonging to the Minister of Defence, Marshal Grigori Tarkovsky. Unlike the other members of the Politburo who chose weekend dachas in a sylvan setting twenty miles to the west of Moscow, Tarkovsky preferred to spend as much time as possible in the city that, as a younger man, he had helped to save from the Germans. Tarkovsky’s favourite record was the ‘1812 Overture’ but when the cannons fired it was Hitler, not Napoleon, who was on the run and the steel plate in his skull that had replaced the bone removed by a German bullet seemed to throb with triumph.

Tarkovsky, sturdy and bleak-faced, grey hair clipped as short as an Army recruit’s, leaned forward, moved a pawn one square and said: ‘So what do you think, Comrade President?’

The President of the Soviet Union – his real power lay in the leadership of the Communist Party, not the Presidency – didn’t reply immediately because he was stunned by Tarkovsky’s previous words.

After a while he moved a knight and reflected that, a few years ago, he would have reacted with tigerish speed to both Tarkovsky’s move on the chess board and his cataclysmic suggestions.

But I am an old man, brooded the President, who was seventy-six, three years older than Tarkovsky; the leader of a pack of old Kremlin wolves whose decisions are all affected by their years. Some, like myself, move ponderously with elaborate caution; others, like Tarkovsky, act with rash impetuosity seeking acclaim before death.

In fact, if you accepted that it was governed by Moscow and Washington, the world was in the hands of old men because the American President was seventy-two.

It was frightening. But, in the Soviet Union at least, it had to be: none of the younger males snapping at the heels of the old wolves had yet attained the political maturity needed to lead Country and Party.

Or do I delude myself? Is a man such as Tarkovsky, whose attitudes were frozen in a war when we lost more than twenty million men, women and children really preferable to a younger contender? Especially now that those attitudes had found such a terrifying outlet.

‘Well, Comrade President?’ Tarkovsky stared at the President across the chess board.

‘I’ll grant you this, Grigori, if you’d put such policies into practice in this game I would have resigned half an hour ago. Now if you’ll excuse me for a few moments …’

As he crossed the lawn a yellow butterfly danced in front of him. It made him more aware of the weight of his big body; he raised his head and straightened his back; sweat trickled down his chest and, like so many Russians, he masochistically longed for winter.

Inside the yellow-walled mansion where Tarkovsky, a widower, lived alone attended by a cook and housekeeper, the President paused in the lofty hall adorned with military memorabilia, and gazed critically at an oil painting hanging above the fireplace. It was a portrait of a man staring defiantly into the future; a middle-aged man, glossed with youth by the artist, with black hair and powerful, shaggy features that had the look of a buffalo about them.

We picked them younger in those days, thought the President as he turned away from the picture of himself painted nearly twenty years ago when he first came to power, and headed for the bathroom.

As he washed his hands he could see through the barred window the figure of Tarkovsky bowed over the chess board. What disturbed him so deeply about Tarkovsky’s plan was that, despite its horrendous potential, it might just work. As a last resort.

Because today, despite the furore they always created, conventional disarmament talks were really academic: the answers to the future of the Earth lay in the space surrounding it, not on its crust. And it was into space that Tarkovsky’s ideas were directed.

As he returned to the chess board on the white-painted table a thrush sang blithely on a branch of the birch tree. Little did it know. Tarkovsky had made his move, a singularly unenterprising one in the circumstances, and was sipping iced tea.

The President sat down and studied the board. An end game and a dull one at that. Chess, too, needed young and agile brains.

‘You have considered my proposition?’ Tarkovsky’s voice quivered with expectation.

‘I have considered it, Grigori.’

‘It’s a startling concept.’

‘Without a doubt. Anything that envisages bringing the United States of America to its knees must be startling.’

‘But it could work. Would work,’ he corrected himself.

‘Ah yes. But at what cost?’

‘There would be sacrifices, of course. But nothing compared with –’

The President held up one hand. ‘I know what sacrifices were made in the Great Patriotic War. I was thinking of the cost to humanity as a whole.’

The thrush stopped singing.

‘Not so great,’ Tarkovsky said, ‘in relation to the benefits Mankind would subsequently enjoy.’

‘You refer to the benefits of Communism that would expand across the world after your coup?’

‘Of course.’ A half lie because, as the President knew, Tarkovsky thought in strategies, not ideologies. Although he wasn’t the only member of the Kremlin élite – Politburo or Presidium – to prefer patriotism to socialism. ‘By the way, I have moved.’

‘I’m aware of that.’ Since the discussion had begun the game had assumed another dimension: the President felt he had to win. He considered the few pieces that each of them had left; positionally he had a marginal advantage over Tarkovsky who was playing black; when he was younger he would have pressed it home until, grudgingly, Tarkovsky would have been forced to resign; but that was before Kremlin scheming had sapped his chess skills; now, at this crucial stage in the game, he found it difficult to concentrate. He swept his bishop across the board with a show of confidence that he didn’t feel and said: ‘Can you really be so sure that it would work?’

‘Quite sure. Provided the aero-space industry can meet the challenge. As you know they have been suspect in the past.’

‘And if they do prove themselves equal to it when would you be ready to act?’

Tarkovsky moved one of his foot-soldiers, a pawn, and said: ‘Early next year.’

Six months. The President put his hand to his chest; sometimes he fancied he could hear the pacemaker. Two veterans, each reliant on a foreign body; what a combination.

Too hastily, Tarkovsky added: ‘Naturally I would only recommend such action in the event of hostile action by the United States.’

‘Naturally.’

It would be pleasant to believe that Tarkovsky thought in terms of deterrents but it would be misleading. Tarkovsky was the personification of Russia’s national complex: she had been attacked and betrayed so often that her reasoning was always belligerent. And who could blame men such as Tarkovsky who had witnessed the German treachery in 1941? No, Tarkovsky would interpret the flicker of a presidential eyelid as ‘hostile posturing’ and, from a position of indisputable superiority, would advise a pre-emptive strike.

And what a strike!

The President advanced a pawn with minimal hopes that he might be able to queen it. Perhaps Tarkovsky, too, was tiring. Pacemaker versus metal plate.

‘At least we agree,’ Tarkovsky said, eyeing his depleted black army, ‘that whoever commands space commands the world. That, with space stations and gunships armed with beam weapons, Man is entering an era more revolutionary than anything it has experienced before.’

A Malev jet taking off from Sheremetyevo airport climbed steeply into the blue sky.

‘It’s ironic.’ the President remarked. ‘that Man can’t even share infinity.’

Tarkovsky shrugged. ‘Whoever rules infinity rules the world. If we don’t take command then America will.’

‘But our first objective must be peaceful co-existence.’

‘Through strength,’ Tarkovsky countered.

The Minister of Defence moved his rook. A mistake. He should have been tightening his meagre defences in preparation for a counter attack. But a man’s true character, stripped of pretence, was always revealed on the chess board. Tarkovsky wanted to be Minister of War, not Defence.

But what of my true character? There it was on the black and white squares. Calculated calm. To the Soviet Union he had brought stability after the twenty-five blood-stained years of Stalin’s reign and the eleven erratic years of Krushchev’s rule.

True, a housewife still had to queue for a loaf of bread but she had a home and she had security and she had a future. That will be my epitaph, decided the President. He Brought Stability. But, of course, Tarkovsky was right: it had been achieved through strength. Military might and political guile.

But when he had taken office he had never contemplated extending his authority into the cosmos. Certainly not beyond the limits of the Space Race. But now, as Tarkovsky had said, Man was poised to colonise space, to inhabit the heavens. Mother Russia had to be as strong in the firmament as she was on Earth.

But am I too old to grasp what has to be done? And is Tarkovsky’s solution the only practical answer?

Tarkovsky cleared his throat.

The President moved another pawn, consolidating. The flamboyant move with the bishop had been a mistake; Tarkovsky’s swagger was infectious.

Tarkovsky reached across the board. They exchanged pawns.

The President said: ‘It’s also ironic that your proposition involves the fleet of Dove space shuttles that we’re building.’

Tarkovsky’s grey eyes appraised the President across the chequered board. ‘Not ironic, Comrade President, deliberate.’ He moved his rook again. ‘Check.’

The President blocked the threat with his bishop, at the same time putting the black rook in jeopardy. And, as Tarkovsky withdrew it, said: ‘I suggest,’ by which he meant order, ‘that you personally draw up a plan of campaign and present it to me. Have you discussed this with anyone else?’

Tarkovsky shook his head.

‘Then don’t.’

Tarkovsky’s hand strayed to the area of skin on his scalp covering the metal plate, a sure sign that he was tired.

The President leaned back in his chair. ‘A draw, Grigori?’ He was tired too.

‘I think I am in a stronger position.’

‘I beg to differ. There’s a long haul ahead but eventually we’ll fight each other to a standstill.’

Stubbornly, Tarkovsky brooded over the board. A gesture, the President guessed, from an old warrior who would never have settled for a draw with the Germans. But finally he accepted the President’s offer. ‘Well played, Comrade President.’

‘Perhaps we both learned from the game.’

‘Perhaps. I feel that I played too cautiously.’

The President sighed: the lesson surely was that Tarkovsky had played too rashly.

When he got back to his apartment on Kutuzovsky Prospect in the centre of Moscow the President summoned to his presence Nicolay Vlasov, the Chairman of the KGB, who lived in the same block.

Vlasov, astute and sophisticated, was a schemer. He was also unrivalled in the arts of survival. He was, therefore, the obvious choice – especially as his survival was currently at stake – to produce an alternative plan to Tarkovsky’s. A plan that would cripple the US in space without introducing the spectre of Armageddon.

But the President didn’t tell Vlasov about Tarkovsky’s proposition.

By consulting Vlasov, the President was, without realising it, establishing a neatly tiered battle order between the reigning colossi of the world, the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

The stakes: Final victory in a conflict that had lasted for nearly forty years.

Later, as dusk descended on the sweating city, Nicolay Vlasov – silver-haired, with greenish eyes and a skull that looked peculiarly fragile – stood at the window of his study, glass of Chivas Regal whisky in his hand, watching the traffic far below and digesting the President’s requirements.

They were formidable – perhaps insoluble would be a more apt description! – but in a way he welcomed them because they gave direction to his current campaign for survival. Ever since the débâcle in 1980 when his plan to debase the American dollar with a disinformation operation at the Bilderberg Conference, the annual get-together of Capitalist clout in the West, had failed ignominiously, his star had been in the descent.