Полная версия

The Pilot Who Wore a Dress: And Other Dastardly Lateral Thinking Mysteries

It continued bitterly cold for the rest of Advent and over the Christmas holiday. Persistently heavy snow fell on Boxing Day and into the following day, as delighted children threw snowballs at their guffawing uncles.

By the end of the month a savage blizzard was sweeping across the country. Freezing gales sculpted the snow into twenty-foot drifts, blocking roads and burying steam trains up to their shoulders.

Wythenshawe in Cheshire was particularly badly hit, and it was here, on 20 January, that the papers reported a disturbing occurrence that had diverted the authorities from their road-clearing, burst-pipe-repairing and train-excavating duties.

Imagine the scene: the body of a man, dressed in a heavy coat over layers of clothing, has been spotted in the middle of a snow-covered field by some children coming home from school for their lunch. One of them, Charlie Shaver, braver perhaps than the rest, crosses the field to look at the body. The man’s face has been blasted away by something like a sawn-off shotgun, a weapon typical in country post office robberies around these parts. He is on his back in the snow, which is stained pink with his blood. There is no sign of a weapon.

Charlie races to the other side of the field and knocks on the door of his auntie, Ada Ferribridge. Ada, who had heard a single gunshot ring out about twenty minutes earlier, at once calls the police, who, keen to get away from shovelling their station forecourt, arrive at the scene with a good deal of important fuss.

They immediately recognise the body as that of local charmer and ladies’ man Raymond Trethewey. His manicured nails and fancy tattoo are known to all the regulars in the pub. Photographs are taken and the body is removed.

The autopsy report describes a short, very slight young fellow, in good nick but minus his appendix. He has died from a shotgun blast fired from below his chin, which has removed his previously handsome face.

Trethewey, it seems, had been on his way to the Cross In Hand pub in the high street, where he always goes for a lunchtime glass of beer with his next-door-neighbour and friend, the blacksmith Jack Ferrario. But today he hadn’t turned up.

Apart from young Charlie’s footprints going towards and away from the body, there is only one other set of marks, quickly identified as footprints made by the wellington boots habitually worn by Trethewey. These are expensive, specially commissioned boots. Though they look like normal wellingtons they have on their sole a handmade tread incorporating the victim’s initials, RWT.

Trethewy’s distinctive boot prints start at his front door and continue unbroken to the middle of the field, where his body lay. They are easy to track because of the monogram, which, up to the position of the dead body, has been very heavily trodden into the deep snow.

But none of this makes sense, because Trethewy is not wearing his famous boots. He has on instead a pair of totally unsuitable moccasins. Furthermore, the boot prints continue from the body in an unbroken line into a copse of trees between the field and the village high street, where they disappear, the snow having not penetrated the overgrown wood. Even odder, the prints beyond the body appear somewhat lighter and less deep, though still heavy enough.

The local police are quick to spot the problems. How can a man in light shoes walk into the middle of a field, leaving boot tracks, shoot himself in the face, and then continue on his merry way, taking his weapon with him?

Stirring a mug of Ada Ferribridge’s steaming tea, Sergeant Swainston remarks that the prints might actually be those of the murderer, who stealthily approached Trethewey, his feet muffled by the snow, shot him, and then continued into the wood, there disposing of the firearm. ‘So where are the victim’s footprints, then?’ asks a young constable, passing round some of Ada’s biscuits. To this Swainston has no answer so he strolls over to the pub to relieve himself of the several teas he has had that afternoon.

As he is emerging from the gents an old man in a cap motions him across. He tells Swainston that the previous day, as today, Trethewey was wearing nothing more than very wet moccasins on his feet, despite the deep snow. He says he had claimed that his boots had been stolen from outside his front door. But he has more …

Two days previously Jack Ferrario had blown his top in the pub, apparently furious that his next-door-neighbour Trethewey had been hopping over their party wall and romancing Ferrario’s wife while he was shoeing horses at the smithy. Ferrario promised that he was going to damage Trethewey’s good looks in a way he wouldn’t be able to fix.

The old chap says that though Ferrario has small feet he is a huge ox of a man and that if he decided to pick up the slight Trethewey, carry him round the pub, and then fling him through the etched-glass window, he’d be able to do it without any trouble.

A light springs up in Swainston’s eye.

The problem

Who has killed Trethewey and where is the weapon? Is blacksmith Ferrario the murderer? If so how did he shoot the victim in the middle of a snow-covered field without leaving any footprints? Where are Trethewey’s boots, why was he wearing moccasins, and why are there no moccasin prints in the field? Finally, why has such a slight man made such heavy impressions with his monogrammed wellies?

Tap here for the solution.

The Yorkshire factory

The mystery

It is a September day in 1925, on the outskirts of a small Yorkshire town tucked into a quiet nook in the Dales. It is lunchtime and the bells from the moorland church are chiming the quarter. Coming over the bridge is a solitary walker dressed in hiking tweeds, his cap pulled down over his eyes against the rain, which is now coming on hard. Across the high street he spies a cosy pub where he decides to shelter and have a bite to eat.

Inside the pub, our walker, whose name is Gerald, shakes the rain from his cap and hangs it on a peg beside the fire. He orders a pint of beer and a piece of cheese from the rosy-faced landlady and looking around the low ceilinged room he spots in the corner an old man in a straw hat, nursing a drink in a china mug.

Gerald leans his stick against the chimney corner and goes over to sit beside the old man. ‘Good afternoon,’ he says.

‘Aye’, replies the man, taking a pull at his ale and drawing a rough sleeve across his muttonchop whiskers.

Through the window Gerald can see, on the other side of a dry-stone wall, a huge Victorian factory building and its handsome reflection in the millstream. A plume of smoke rises from the chimney, and the factory name, S. GARTONS, is reflected in gigantic back-to-front capitals in the water. The old man removes the long clay pipe from his lips and says, ‘You’re not from round here, are you?’

‘No,’ replies Gerald.

The man pauses. ‘I’ll tell you what, lad,’ he says. ‘If you can tell me in one guess what it is they make in that factory I’ll buy you as much beer as you can drink. If you fail, you’ll do the same for me. One guess only.’ Gerald muses for a minute, staring into the shimmering water of the millstream opposite.

‘Well, I’ve no idea,’ he says. Then he takes a longer look at the name reflected in the water. ‘All right,’ he says suddenly, ‘I’ll tell you.’

The old man grins. ‘What is it then?’

‘Handkerchiefs!’ exclaims Gerald.

‘You cheated! You knew already,’ gasps the man.

‘No I didn’t,’ says Gerald. ‘It was easy.’

The problem

How did Gerald know what was made in the factory?

Tap here for the solution.

The riddle of the Burns supper

The mystery

John and Joan Jones live in a charming 18th-century cottage near Matlock in Derbyshire, on the south-eastern cusp of the Peak District. From their bedroom windows their two children Julie and Jeremy often look out across the craggy sheep-sprinkled vista, which stretches from the low screen of evergreen trees at the bottom of their back garden out as far as the eye can see.

They watch the ravens circling and cawing overhead, tearing worms from the damp earth, or dropping snails from a height onto the limestone outcrops as if cracking nuts. At night a low wind is often to be heard moaning under the eaves and rattling the handle of the Joneses’ garden shed.

The Joneses are a happy family. John Jones is a Scotsman who teaches business studies at Buxton’s Espurio University. Joan Jones is a full-time mother. Their cheerful children catch the bus to school every day and are both doing well. Jeremy is good at drawing and Julie likes maths. They help their mother around the house but from time to time Jeremy is mischievous, blowing raspberries at the dustmen through a hole in the hedge or letting his beagle Tinker off the lead when he goes into town.

One Sunday morning Mr and Mrs Jones return home in the early hours after a roisterous Burns Night supper in town. Letting themselves into the house in the pitch black, they relieve the babysitter and push straight off to bed.

Mrs Jones wakes later than usual the next morning. She had rather more sparkling wine than she’d meant to the previous night and John polished off a bottle of malt whisky with a couple of friends. Today her head is throbbing and he is snoring for Scotland.

Mrs Jones gingerly opens the bedroom curtains to take a look at the morning. The sun is streaming onto the front lawn and it is a good deal warmer than it has been over the past week, which is nice.

But Joan notices something unusual. Lying on the wet lawn are some objects that she cannot identify. Pulling on her dressing gown, she goes downstairs and turns on the kettle in the kitchen before padding over to the front door. She opens it a crack to have a better look at the things on the grass.

In the middle of the lawn are eleven pieces of coal, each very roughly the size of a walnut. They are not far apart and appear to have been placed together deliberately. Lying nearby all on its own is a large carrot, which a raven is eyeing from the wall. Somebody, presumably the person who placed the other objects on the lawn, has left his or her scarf on the grass, and it is now soaking wet. The scarf is of a very common design and looks rather moth-eaten. It certainly isn’t one Mrs Jones would allow John or Jeremy to wear in a similar state.

Behind her, Joan Jones hears the tread of Jeremy on the stairs. His hair is up on end and he is holding a jam jar with a snail in it. ‘Malcolm wants some lettuce,’ says Jeremy.

‘Good morning to you too,’ says his mother, shutting the door. ‘I hope you were good last night.’

‘Suzanne let us watch The Exorcist,’ says Jeremy. Joan makes a mental note to think twice about the suitability of Suzanne as a babysitter next time.

‘What do you know about those things on the lawn?’ says Mrs Jones suspiciously, swallowing a couple of aspirin and pouring boiling water into two mugs. ‘Did you put them on the lawn?’ Jeremy smiles and shakes his head. He pours some sugar-coated breakfast cereal into a bowl and adds nearly a pint of milk and a good deal more sugar. ‘What about Julie?’ asks his mum.

‘No,’ replies Jeremy with his mouth full, ‘she didn’t put them on the lawn either. Nobody did.’

Mrs Jones is bemused but doesn’t fancy an argument. She also decides against breakfast. ‘Not too much noise this morning, darling,’ she tells her son. ‘Your father had a busy day yesterday.’ She carries the coffee cups upstairs, trying, between hiccups, to solve the mystery of the strange objects arranged on her lawn.

The problem

Jeremy was telling the truth. Nobody put the strange assortment of objects on the Joneses’ lawn. But there is a very straightforward reason why they are there. What is it?

Tap here for the solution.

The annoying computer password

The mystery

Children these days seem to have little trouble remembering twenty computer passwords, yet they still cannot remember the kings and queens of England. Why should they, when they can look them up on their iPhone?

Older people often have trouble remembering where they live and their own names, let alone recalling their PIN number, mobile number, telephone banking security questions and all that stuff.

I don’t know who is responsible for the following joke about computers – I wish I did – but it kind of sums up the situation.

COMPUTER: Please enter your new password.

USER: cabbage

COMPUTER: Sorry, the password must be more than 8 characters.

USER: boiled cabbage

COMPUTER: Sorry, the password must contain 1 numerical character.

USER: 1 boiled cabbage

COMPUTER: Sorry, the password cannot have blank spaces.

USER: 50fuckingboiledcabbages

COMPUTER: Sorry, the password must contain at least one upper-case character.

USER: 50FUCKINGboiledcabbages

COMPUTER: Sorry, the password cannot use more than one upper-case character consecutively.

USER: 50FuckingBoiledCabbagesShovedUpYourArseIfYouDon’tGiveMeAccessNow!

COMPUTER: Sorry, the password cannot contain punctuation.

USER: ReallyPissedOff50FuckingBoiledCabbagesShovedUpYourArseIfYouDontGiveMeAccessNow

COMPUTER: Sorry, that password is already in use.

Anyway, the point is to tell you about a man named Bill, who could never remember how to spell his password. He was alert, sane, and happy with computers, but spelling had always been a bit tricky for him. It wasn’t just unusual words like ‘acquit’ and ‘minuscule’ that gave him trouble, it was ordinary words with double letters, like ‘misspell’ – somewhat ironically.

The most annoying of the lot was his password, which he never could spell correctly, so that he spent many wasted hours trying to log on to his computer.

The problem

How did Bill spell his password?

Tap here for the solution.

Terry’s girlfriends

The mystery

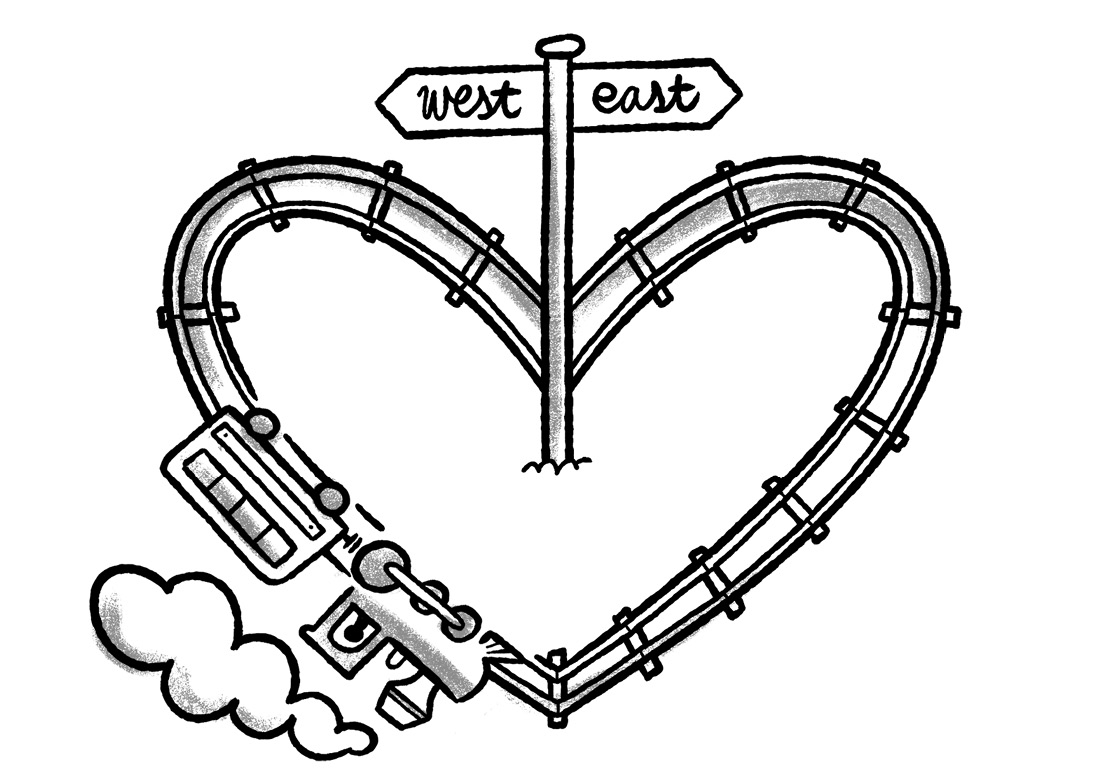

Terry is a young man with two girlfriends: Emma, who lives to his east, and Wendy, who lives to his west. Emma East is a petite and sultry redhead; Wendy West is a blonde volcano – cool on the outside but bubbling hot below the surface ice. Terry likes both girls equally and enjoys the company of one just as much as the other.

Terry’s local railway station has only one platform. It is one of those ‘island’ platforms of the sort where trains on one side always go one way and trains on the other side always go the opposite way. There is an unfailingly reliable hourly service in each direction, east and west, the trains always run on time, there are the same number both ways, and no train is ever cancelled. (You’ll have noticed that this is very unlike the real world.)

Unfortunately, Terry is completely disorganised, with no idea of the actual times of either service. In one respect this doesn’t matter, because Terry’s girlfriends never go out. They are so devoted to him that they’re always at home in their respective houses, looking out of their front window, waiting for him to visit.

Every time Terry fancies some female company he leaves home without consulting a watch or clock, goes straight to the station, buys a ticket valid to either station, runs up the steps to the middle of the island platform, and boards the first train that comes in, whether eastbound or westbound. There’s one of each every hour and they are perfectly normal trains in every way. He catches his trains at random times and on random days. Sometimes he gets there late in the evening. Sometimes it’s early morning. Sometimes it’s lunchtime, sometimes teatime. He arrives on any and every day of the week in no particular order and he goes either east or west according to which train arrives first.

The westbound train, going to Wendy, leaves at exactly the same time past each hour. The eastbound ‘Emma’ train does the same but leaves at a different time from the westbound ‘Wendy’ train, so Terry is never torn between the two.

The problem

Last year Terry saw Emma East a lot, and many more times than he saw Wendy West. In fact, he hardly saw Wendy West at all. Why?

Tap here for the solution.

The lorry driver slaying

The mystery

The Sting is a 1973 film starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford. It covers the ups and downs of two confidence tricksters as they try their hand at everything from racing scams to cheating at cards. There are several other successful films on the same subject, which makes you wonder what it is about conmen and card-sharps that provides this mysterious allure.

The most polished card cheats are very skilled and slick. You’ve got the ‘mechanics’, who use sleight of hand such as second dealing, whereby the top card is retained on the pack by the thumb while the second card is invisibly slipped out under it in the process of the deal. Then there are the ‘stackers’, who can arrange the cards in a useful order while shuffling. There are the ‘paper players’, who use marked cards, and there are ‘hand muckers’, who cleverly conceal cards in their palms and switch them for other less useful cards during play.

Most amateur cheats keep things simple, using less complicated methods such as ‘shorting the pot’ (quietly putting in less money for their bet than they say) or peeking at other players’ cards. The benefit of the simple approach is deniability.

A fine example of suspected cheating of the sophisticated sort came one chilly December day in 2011 at a roadside café near Newcastle, where a group of lorry drivers had finished their egg and chips and were playing a game of poker.

The game had been going some time and the pot was huge. The card players were all experienced, and very good at what they were doing. There was no chat and the focus was on the game. Cards were held close to chests and mugs of tea were going cold. Glances passed back and forth, but the stony poker faces gave nothing away.

Several players clearly thought they had good hands, and betting was serious. A great wad of money had built up in the centre of the table. Then came the moment. The dealer laid down, in dramatic fashion, one card at a time, a perfect royal flush in Spades: Ten, Jack, Queen, King and Ace, the strongest possible poker hand, and an unlikely one.

For a moment a hush fell upon the group. The dealer’s face showed no emotion. Outside, the engines of arriving vehicles appeared to fall silent. Then one of the men, large and broad-shouldered, stood up, knocking his metal chair onto the tile floor. ‘You’re a cheat!’ he announced determinedly, aiming a stout forefinger at the dealer. ‘And I can prove it.’ The dealer didn’t speak but instead, in front of a whole table of witnesses, silently drew a long knife and stabbed the man through the chest, killing him on the spot.

The café owner locked himself into his room and immediately called the police, who arrived quickly. As a trickle of blood continued to run from the table into the spreading red pool on the floor they interviewed all the lorry drivers and also the café owner. All the men agreed on the dealer’s guilt and even the dealer admitted the stabbing, though not the cheating.

But, after hours of questioning, a confession, and clear evidence that the dealer was guilty of the murder of an innocent card player, not a single man was arrested – not even for illegal gambling – and every one of them was allowed to walk free and drive his lorry home.

The problem

Why, when the police had the dealer’s confession and the agreement of everyone around the table on the dealer’s guilt, did the police let every single man off scot-free?

Tap here for the solution.

The magic bucket

The mystery

Stuart O’Brien is a successful businessman, with silvering hair, a flash car and an imposingly ugly mansion in the Surrey countryside.

Stuart left school without taking any exams but used his persuasive skills to land himself a job in the sales team of Polyplastika, a plastics manufacturer. The company turns out drainpipes, washing-up bowls, industrial pallets and buckets by the thousand.

Stuart was always a fantastic salesman and rose through the company ranks very fast. His friends call him ‘Irish Stu’, and say that he hasn’t so much kissed the Blarney Stone as stuck his tongue down its throat. By the time he was twenty Stu was heading the firm’s sales team and was beginning to earn serious money.

Stu is now strengthening the firm’s toehold in China, he’s on the company board and is being tipped as the firm’s next CEO. He plays golf to a handicap of four, buys the most expensive foreign colognes and has just treated himself to a pair of enormous Tudor garage doors. Life is good.

Stu is married to Laverne, a tall blonde with an expensive taste in handbags and holidays. She has a mouth full of uncannily white teeth, which flash like urinals in a cave.

Apart from looking good on Stu’s arm at company dos and trips to the Far East, Laverne is a great party-giver. At their annual summer barbecue, held at the O’Briens’ vast Surrey home, Laverne circulates in the garden in unlikely heels, topping people up by the pool, putting little umbrellas in their glasses, and doling out to each of them at least eleven seconds of her white-urinal smile. And it’s at the barbie that Stu always does his party piece.

Someone hands him one of the company’s famous plastic buckets – he prefers to use a red one. He then hands back the lid, which he doesn’t need, and fills the bucket to the very brim with warmish water. He now asks for silence while he slowly turns the bucket upside down. It remains full. Not a drop spills out. He doesn’t swing it round his head, add anything to it, or put anything on the top – it’s an open bucket full of nothing but water. To prove the point, he puts his hand into the upside-down bucket and brings it out wet, shaking and flicking a few drops at his friends.

After a couple of seconds, or longer if people ask, he turns the bucket right-way up again. It contains just as much water as it did at the start. He hands it to Laverne, who can barely hold it because it’s still full to the brim.