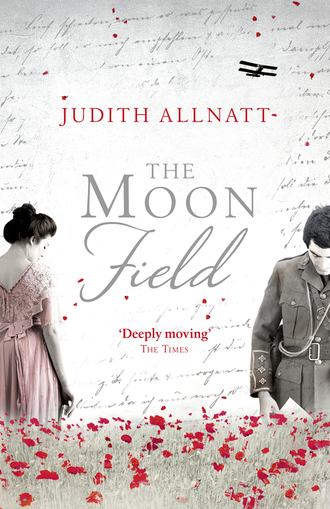

The Moon Field

Полная версия

The Moon Field

Жанр: книги по психологиикниги о войнеисторическая литературасовременная зарубежная литературазарубежная психологиясерьезное чтениеоб истории серьезно

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2018

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу