Полная версия

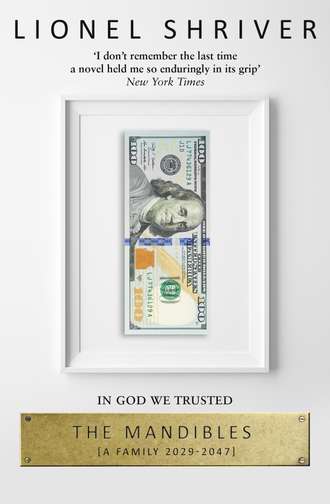

The Mandibles: A Family, 2029–2047

“No, they can’t. All former vulnerabilities have been secured.” Florence was uncomfortably aware of reciting this received wisdom with a slight singsong.

“That’s what people say. That doesn’t mean it’s true.”

“Willing, I’ve no idea how you got to be such a cynic by the age of thirteen.”

He glowered. “They could do worse than knock out the internet.”

“Stop it. You’re letting your imagination run away with you. The point is, none of what you told me the president announced on TV has anything to do with us, okay?”

“Everything has to do with everything else,” he announced grimly.

“Where did you get that?”

“From the universe.”

“Jesus, my son’s become a mystic. Lighten up. Let’s have some ice cream.”

Given that he was eternally free to watch the other two-thousand-some channels streamed en español, Florence knew better than to believe that Esteban was watching the second delivery of the address in Spanish to “maintain his fluency.” Still jubilant over Dante Alvarado’s narrow victory in 2028, he was basking. During this first honeymoon year, for hardcore supporters like Esteban, America’s first Lat president could do no wrong.

The other slightly-less-than-half of the country was if anything more sullen than in 2008, but also more prone to keep their mouths shut. This time around, no dyspeptic “birthers” could object that the Democrat was born outside the country. Its passage greatly assisted by Arnold Schwarzenegger’s failed bid for 2024, the Twenty-Eighth Amendment nullified the arcane constitutional requirement that presidents be born on American soil. (Florence wasn’t the only one who attributed the Terminator’s surprise defeat to the eleventh-hour incumbency gimmick of nominating Judith Sheindlin—a.k.a. “Judge Judy”—to the Supreme Court. The Court’s sessions had been livelier since, and shorter.) Dante Alvarado being unabashedly born in Oaxaca had helped to get him elected. The fact that many DC press conferences and congressional debates were now conducted in Spanish was an enduring source of pride for Esteban’s community. Although some Democrats regarded Alvarado’s decision to deliver his inaugural address in January exclusively in his native language as gratuitously provocative, Florence didn’t care. The broadcast of that soaring, historic speech on the Washington Mall had provided a welcome opportunity to brush up on her own Spanish.

Besides, back in 2024 she’d put herself on notice that Florence Darkly was a racist.

At 5:08 p.m. that fateful Saturday in March, she and Willing had been shopping in Manhattan, taking advantage of the blowout spring sale at the sprawling Chelsea branch of Bed Bath & Beyond. They’d just got through checkout when the store’s lights went off. Out on the street, the sidewalks were jammed with people shaking out fleXes in frustration; checking for connectivity on her own fleX was as compulsive as it was futile. A blackout was one thing—the whole area seemed to have no power—but that didn’t explain the absence of satellite coverage. People poured out of the subway stations; the trains had stopped. The stoplights out, an accident at West Nineteenth Street had brought traffic on Sixth Avenue to a standstill. The cacophony of horns was strangely comforting: signs of life.

Clutching her son’s hand, she hadn’t yet entered the world in which refusing to relinquish their new wicker laundry hamper was ridiculous—though its being weighed down with other bargains stuffed inside made the bulky object especially awkward. As they negotiated their way through crowds milling toward hysteria, her struggling with the white elephant must have been conspicuous. When a muscular Mexican attempted to take it away from her, she assumed he was undocumented and a thief, using the pandemonium to hustle. She yanked the hamper back.

The man promised her in soothingly correct English that he was only trying to help. He said no one he’d spoken to seemed to know why suddenly nothing worked, because the very devices with which you answered such questions had ceased to function. He warned her that, clutching the hamper with one arm and a child with the other, she risked being trampled. He asked where they lived; she was reluctant to tell him, but didn’t want to be rude. He said he also had to get home to Brooklyn. He suggested they take the Manhattan Bridge, whose pedestrian ramp would be less popular than the Brooklyn Bridge one, sure to be mobbed. He hoisted the loaded hamper on his shoulder. At first they didn’t talk. He terrified her. But as he prowed through crowds across Eighteenth Street, then down Second Avenue to Chrystie, she had to admit that she’d never have carried their chattel so far on her own, nor would she have as expertly navigated the most direct route to the pedestrian entrance at Canal Street without an app. He was right about the choice of bridge. They weren’t jostled so badly that they were ever in danger of being pushed over the rail into the East River.

On the ramp, they all agreed that the hardest part was not knowing what had happened. On every side, other pedestrians volunteered their sure-fire theories: Halley’s Comet had hit New Jersey. The government was conducting a security drill. There’d been another terrorist attack. Harold Camping’s notorious prediction that the Rapture would arrive on May 21, 2011, was only off by thirteen years, nine months, and fifteen days.

When they finally curved down the ramp to their borough, she begged to assume the burden and proceed with her eight-year-old’s help. Their Mexican escort claimed to live in Sunset Park, six miles west of East Flatbush, and his continuing in the wrong direction didn’t make any sense—unless he planned to accost her.

Yet by now it was dark, obliteratingly so. Only individual fleXpots penetrated the blackness. Behind them, Manhattan could have been a mountain range. Traffic perfectly gridlocked, since driverless functions and onboard computers relied on the internet, most cars had been abandoned, though families huddled inside a few sedans, doubtless with the doors locked. So the Lat insisted not only on seeing them home, but on depleting his fleX to light the way. By the time the trio was trudging up Flatbush near the park, his fleX went dead, and they had to switch to Florence’s. The avenue was lined with other pilgrims and the waning glow of their small devices, like penitents with luminarias. The whole trip on foot was nearly ten miles and took four and a half hours. So by the time they turned onto Snyder, Florence assumed the hamper and let their protector carry Willing, who fell asleep in his arms. Later the man would explain that of course he’d been scared, as everyone was scared, but that the surest way to keep his head was to concentrate on the safety of these two strangers. His name was Esteban Padilla, and by the time they reached East Fifty-Fifth Street, dog-tired, fully in the dark again because Florence’s fleX was shot now, too, in need of locating candles and matches in the kitchen on their hands and knees, Florence was a lot less of a racist and in love.

Last November’s election meant so much to her partner that she’d kept a slight queasiness about the new president to herself. Oh, she was thrilled by the symbolism; after all the acrimony over immigration, a Lat in the White House was the ultimate emblem of inclusion. Yet the man had a baby-faced softness only emphasized by the palatalized consonants of a Mexican accent, which in Alvarado’s case sometimes seemed a bit put on. (When he spoke to white audiences during the campaign, his pronunciation crisped right up.) It wasn’t only that he was fat—what the hell, three-quarters of the country was fat—it was the kind of fat. He had a momma’s boy puffiness that might make foreign heads of state regard him as a pushover.

Pulling down bowls, Florence debated asking Kurt to join them for ice cream. She was always of two minds about how much to enfold their basement tenant, a part-time florist, into the family’s social life. He was sweet about bringing back aging bouquets that would have been thrown away, cheering their home with freesias. And she liked him well enough, which she wished he would simply register and then relax. After all, he was polite, solicitous, intelligent, well spoken, and eager. (Overeager? And eager for what? To be liked, obviously, and even being liked well enough would have sufficed.) Yet his outsize gratitude for every common kindness was exhausting. The fact that he never complained made their lives easier, but he’d every right to complain. Tall for the low ceiling downstairs, he perpetually hit his head on the crossbeams, which she should have cushioned with foam appliqué. An amateur musician, he would only practice the sax with no one else home, while upstairs, even Willing’s light, stealthy tread translated into elephantine pounding from below. Did Kurt Inglewood even plead with the family to keep the TV low? No, no, no. So what tilted the balance this evening toward three bowls not four made Florence feel sheepish.

Roughly her age, trim and nicely proportioned, with a long, sharply planed face, Kurt should have qualified as handsome. A guy with a middle-class upbringing who’d struggled from one unsatisfying, low-paid job to another just as Florence had, Kurt would have come across as a charming and competent striver waiting for one decent break when he was younger. But one of the corners he’d cut for years was dental care. Decay had blackened an engaging smile into a vampiric leer. Absent fifty grand’s worth of implants, fillings, and bridges, he’d be single for life. Now in his forties with those teeth, he’d tipped tragically, unfairly, and perhaps permanently into the class of loser—an ugly, dehumanizing label that she had narrowly escaped herself. She encountered no end of poor dental hygiene at the shelter, and maybe that was the problem tonight. She wouldn’t have minded sharing ice cream with Kurt-as-Kurt. But it had been a long day at Adelphi, and she simply couldn’t face that smile.

Florence dished up three scoops. Feeling that edgy gaiety of something major having happened even if she couldn’t tell yet if it was good or bad, she impulsively put a chunk of peppermint chip in Milo’s dog dish. They convened in the living room with spoons, and Esteban turned off the TV.

“So what’s your take on the address?” she asked Esteban as they lounged with dessert on the sofa.

“Está maravilloso,” he declared. “Those decrepit Republicans—they’re always carping about how Alvarado is weak and spineless. This’ll show them. Talk about standing up for this country! That’s the nerviest set of policy decisions I’ve heard from any president in my life. They can’t call him a pussy now.”

Florence guffawed. “They might call him some other things. Like a grifter.”

“Only people get hurt deserve it,” Esteban said confidently. “Bunch of Asian assholes. Who gives a shit.”

Densely silent since their conversation in the laundry room, Willing emerged from his stewing with a prize-winning non sequitur: “We could always move to France.”

“Oka-ay …,” Florence said, stroking her son’s neck with a forefinger as he sat rigidly on the floor. His ice cream was melting. “And why would we do that?”

“Nollie lives in Paris,” Willing said. “It might be safer. The president said they won’t let dollars out of the country. He didn’t say they won’t let people out. Yet.”

Florence glanced at Esteban and shook her head like, Don’t ask. “I suppose you might visit your great-aunt someday. You two seemed to get on well during her last trip to New York.”

“Nollie does what she wants. Everyone else does what they’re supposed to,” Willing said. “Jayne and Carter say she’s selfish. That might be a good thing. It’s the selfish people, a certain kind of selfish, who you want on your side.”

Florence assured her son that there were no “sides,” observed that he was overtired, urged him to bed, and finished his ice cream, now turned to soup. After he’d brushed his teeth, she murmured in the boy’s doorway that no one was moving anywhere, and that lots of events that seem strange and scary up close end up looking like the plain ups and downs of regular life later on. The Stone Age seemed like the end of the world, didn’t it? And it wasn’t.

Yet later her own sleep was troubled. The disquiet was subterranean. Bedrock was shifting—what had to stay the same in order for other things safely to change. In 2024, Florence came to appreciate the vast difference between something bad happening and the very systems through which anything happens going bad. Even if the president’s somber decrees had no concrete impact on the day-to-day in East Flatbush, the edicts seemed to challenge her life at ground level—not so much the trifling to-and-fro of what she earned and what she spent, what she did and where she went, but who she was.

Walking to the bus stop the next morning, Florence crossed to drop the Con Ed bill in the mailbox—a payment method that felt as primitive as lighting a fire with flint. So history could reverse. Now that any transaction involving vital infrastructure or finance had to be conducted offline by law, trashy, space-eating paper bank statements and utility bills once again littered domestic tabletops. The checkbook, too, had been salvaged from the dustbin of the past, hairballs and used dental floss clinging between its leaves. But at least the necessity of scrawling on a rectangle “Two hundred forty-three and 29/100s” alone justified mastery of the formation of letters by hand. Close to losing the skill altogether, she’d been forced to void the first Con Ed check at breakfast because it was illegible. So she’d tutored Willing on printing the alphabet, since they didn’t teach handwriting in school anymore. Most of his classmates couldn’t write their own names. This was progress? But that was an old-fashioned concern that kids considered drear.

As the envelope fluttered into the blue maw, she frowned. If “internet vulnerabilities” had been fixed, why did we still have to pay electric bills by check?

The “gentry” encroaching ever farther east into Brooklyn took private transport. As usual the only white passenger on the standing-room-only bus, Florence strained to pick up any reference to Alvarado’s address. The Afri-mericans spoke their own dialect, only partially discernible to honks, infiltrated by scraps of mangled Spanish. Among the Lats, the only rapid urban Spanish she could confidently translate concerned the latest music rage, beastRap, comprising birdcalls, wolf howls, lion roars, cat purrs, and barking. (Not her thing, but when artfully mixed, some of the songs were stirring.) A screeching seagull tune with an overlaid rhythm track of pecking seemed to generate more excitement on the B41 than the wholesale voiding of American bonds. Yet once the news filtered down to the street, gold nationalization wouldn’t go down well with this crowd, many of whose toughs were looped with gleaming yellow chains. It was hard to picture these muscular brothers and muchachos lining up patriotically around the block to deliver their adornments to the Treasury. With the likes of that hulking weight-room habitué looming by the door—were the feds planning to wrestle him to the pavement and yank out the gold teeth with pliers?

A generation ago, this stretch of Flatbush Avenue north of Prospect Park was trashy with the loud rinky-dink of carpet warehouses, discount drug stores, nail salons, and delis with doughnuts slathered in pink icing. But after the stadium was built at the bottom of the hill, the neighborhood spiffed up. The “affordable housing” that developers promised as part of the stadium deal with the city was nearly as costly as the luxury apartments. Flatbush’s rambunctious street feel had muted to a sepulchral hush. Pedestrians were few. The bee-beep of the private vans that used to usher the working class up and down the hill for a dollar had been replaced by the soft rush of electric taxis. The avenue was oh, so civilized, and oh, so dead.

Florence rather relished the fact that the commercial transformation of the once vibrant, garish area must have put the well-heeled new residents to no end of inconvenience. Oh, you could get a facelift nearby, put your dog in therapy, or spend $500 at Ottawa on a bafflingly trendy dinner of Canadian cuisine (the city’s elite was running out of new ethnicities whose food could become fashionable). But you couldn’t buy a screwdriver, pick up a gallon of paint, take in your dry cleaning, get new tips on your high heels, copy a key, or buy a slice of pizza. Wealthy residents might own bicycles worth $5K, but no shop within miles would repair the brakes. Why, the nearest supermarket was a forty-five-minute hike to Third Avenue. High rents had priced out the very service sector whose presence at ready hand once helped to justify urban living. For all practical purposes, affluent New Yorkers resided in a crowded, cluttered version of the countryside, where you had to drive five miles for a quart of milk.

Florence hopped off at Fulton Street and headed east with her collar pulled close. Fall had been merciful so far, and this was the first day of the season the wind had that bite in it, foretelling yet another vicious New York winter. The jet stream seemingly having hove south across the whole country for good, the anachronism global warming had been conclusively jettisoned in the US. She hung a left on Adelphi Street, whose traffic had grown lighter now that the underpass was closed off a few blocks farther up; ever since the horrendous collapse of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway along Hamilton Avenue, not far from her parents’ house, no one was allowed to come near it.

She assessed the intake line as pro forma: about twenty families, the ubiquitous strollers looped with as many bags as they could carry without toppling over. Several adults were smoking. These were some of the last holdouts who puffed on real cigarettes, despite their being far pricier than steamers. Ridiculous, since she’d never been addicted herself, but the sharp, toxic scent of tobacco made Florence nostalgic.

On a leafy street in Fort Greene, the Adelphi Family Residence was formerly a private apartment building willed to the city by a childless landowner—one of a torrent of bequests that had poured into public coffers as well as into private charities from the boomer generation, a hefty proportion of which had neglected to reproduce and had no one else left to be nice to. The tall, tawny-bricked building with period details was a big step up from the much-discredited and now-defunct Auburn shelter in the projects a few blocks away. To accommodate more residents, the apartments had been carved into stingier units with no kitchens and communal bathrooms, but there was also a cafeteria and nominal rec room (whose Ping-Pong tables never had balls). Funny, she and Esteban could never afford this tony a neighborhood in a million years.

Florence waved at Mateo and Rasta, the guards at the entrance, then threw her backpack on the lobby’s security belt and did a stylish twirl in the all-body X-ray. (Mere metal detectors no longer cut it. Plastic gun replicas made from home 3-D printers had improved.) It was too bad that the lobby’s intricate nineteenth-century tiling was obscured by posters—home is where the heart is!; success is just failure tried one more time!—though the cheerful admonishments helped to compensate for the grimmer notice, verbal or physical abuse of staff will not be tolerated.

Adelphi wasn’t the vermin-infested hellhole teeming with sexual predators that her pitying neighbors like Brendon the Financial Clairvoyant no doubt imagined. What depressed Florence about her job, then, wasn’t squalor, or even the poverty and desperation that drove people here. It was the aimlessness. The collective atmosphere of so many people in one place having lost any purposeful sense of traveling from point A to point B—that milling-about-and-waiting-to-die fug that penetrated the institution—disquieted her not for its contrast with her own driving, forward-thrust story, but for its reflection of how she, too, felt much of the time. At Barnard, she’d never have imagined herself mopping up vomit with the best of them, save perhaps in a charitable capacity, in some brave, brief experimental phase before getting on with her career. She didn’t understand how she ended up at Adelphi any more than its residents did. She didn’t know what could possibly lie on the other side of this place for her any more than they did, either. While crude survival from one day to the next might be every human’s ultimate animal goal, for generations the Mandible family had managed to dress up the project as considerably more exalted. Motherhood might have provided a sense of direction, and Willing did give gathering indications of being bright—but the smarter he seemed, the more she felt impotent to do right by his talents. Unlike Avery, she’d no problem with Willing being taught in Spanish, so long as he was taught. Yet every fact he volunteered, every skill he exhibited, either she had taught her son or her son had taught himself. The school sucked.

An armed security guard behind her, Florence assumed the desk in the lobby and processed the morning’s arrivals. As ever, a handful of families imagined they could simply show up at the door and grab a bed. Ha! So she’d send them to the DHS intake in the South Bronx, along with a voucher for the van parked outside. Few would be back. Qualifying as homeless was an art, and God forbid you should mention a great-uncle with a spare room in Arkansas or you’d be on the red-eye bus to Little Rock that night. For the others who’d jumped the hoops, arriving with fattening sheaves of documents in sticky plastic binders, Adelphi had barely enough vacant units, and larger families would be crowded. The shelter operated at maximum capacity because two-thirds of the units were permanently bed-blocked. In theory, shelter accommodation was temporary. In practice, most residents lived here for years.

Florence ushered the new families to their quarters, parents clutching pamphlets of rules and privileges. In the rare instance that the family hadn’t lived in a shelter before, the environs came as a shock. Rooms were equipped with dressers missing drawers and mattresses on the floor, with the odd kitchen chair but seldom a table to go with it. Though Adelphi had a few OCD neatniks, most occupied units were piled thrift-shop high with clothes in every corner, the floors junky with plastic tricycles, broken bikes, and milk crates of outdated electronics.

So the intake always complained: What, you telling me there a shared baffroom? Where Dajonda gonna sleep, she sixteen—ain’t she get a room with a door? What do you mean we can’t have no microwave? Them sheets, they stained. Lady in the lobby say these TV don’t get Netflix! Melita here allergic to wheat—so don’t you be serving us any of that soggy pasta. Not much of a view. From our old room in Auburn, you could see the Empire State Building!

Florence always shimmered between two distinct reactions to this inexorable carping: I know, I would hate to share a bathroom with strangers myself. Being homeless doesn’t mean you don’t value privacy, and if I had a teenage girl in one of these places I’d keep her close. The policy on microwaves is unreasonable, since warming up a can of soup hardly means the room gets infested. Homeless people have every reason to value clean linen, to hope for quality entertainment, and to expect their dietary requirements to be catered to. Me, I hate overcooked pasta. Overall, it makes perfect psychological sense that, brought this low, you would want to firmly establish that you still have likes and dislikes, that you still have standards.

A millisecond later: You are in the most expensive city in the country if not the world. You have just been given a free place to live, three free meals a day, free electricity, and even free WATER, while people like me working long hours in jobs we don’t always like can barely stretch to a chicken. For reasons beyond me, you have seven children you expect other people to support, while I have only the one, for whom I provide clothing, food, and shelter. You may have to share a bathroom, but your old-style torrent of a shower beats my “walk in the fog” by a mile, so put a sock in it.