Полная версия

The Idiot Gods

My grandmother moved closer to me through the cold water. Her eyes, as blue and liquid as the ocean, caught me up in her fondness for me and swept me into deeper currents of cobalt, indigo, and ultramarine, and the secret blue-inside-blue that flows within the heart of all things. She asked, ‘Do you remember what I said about you on the day you were born?’

‘You said many things, Grandmother.’

‘Yes, I did and these words I would like you to remember: How noble you are, in both form and faculty, Arjuna, how like an angel in action, and in apprehension like a god! The beauty of the world you are and all of my delight.’

I did remember her saying that. She told all her grandchildren the same thing.

‘How noble would it be,’ she now asked me, ‘for us to break our promise to the Others?’

‘But we are so hungry! They would not mind if we took a single bear.’

‘The Covenant is the Covenant,’ she told me, ‘whether or not you think the Others would mind.’

‘But we made it so long ago, in a different age. The world is changing.’

‘The world is always the world, just as our word is always our word.’

‘Can we never break our word, even as the ice breaks into nothingness while the world grows warmer?’

‘The ice has broken before,’ my grandmother reminded me.

For a while, she sang to me and our family of our great memories of the past: of ages of ice and times of the sun’s heat when the world had been cooler or warmer.

‘Yes, but something is different this time,’ I replied. ‘The world has warmed much too quickly.’

Although she could not deny this, she said, ‘The world has its own ways.’

‘Yes, and those ways are changing.’

Alnitak came closer and so did my mother, and through the turbid, gray waters we debated how the northern ice sheet could have possibly melted so much in the span of a few generations. As I was still a young, not-quite-adult whale, I should have deferred to my elders. I should have felt shame at my questioning of them. Who was I to think that I might have discerned something they had not? And yet I did, and I sensed something wrong in my family’s understanding. In this, I experienced a secret pride in my insight and in my otherness from people who had seemed so like myself in sensibility and so close to my heart.

‘It is the humans,’ I said. ‘The humans are warming the world with the heat we have felt emanating from their boats.’

‘That cannot be enough heat to melt the ice,’ Alnitak said.

‘Only a few generations ago,’ I retorted, ‘only a few humans dared the ocean in cockle shells that we could have splintered with one snap of our jaws. Now their great metal ships are everywhere.’

‘To suppose that therefore the humans can be blamed for the ocean’s warming,’ my grandmother said, ‘is a wild leap in logic.’

‘But they are to blame! I know they are!’

‘How can you be sure?’ And then, as if I was still a babe drinking milk, she chided me for making a basic philosophical error: ‘A correlation does not prove a causation.’

And chided I was. To hide my embarrassment (and my defiance), I took refuge in a little play: ‘Thank you for the lesson, Grandmother. I was just giving you the chance to exercise your love of pedagogy.’

‘Of course you were, my dear. And I do love it so! I have no words to tell you how much I look forward to the day when it is you who teaches me.’

‘I am sure that you could think of a few words, Grandmother.’

‘Well, perhaps a few.’

‘I await your wisdom.’

‘I can hear that you do,’ she said. ‘Then listen to me: it is a heavy responsibility being the wisest of the family – perhaps you could relieve me of it.’

‘No, I cannot,’ I said sincerely. ‘You know I cannot.’

‘Then will you let us leave this bear to his fate?’

All my life, my grandmother had warned me that my innate tenacity could harden into pertinacity if I allowed this. Did anyone know me as did my grandmother?

‘We are hungry,’ I said simply.

‘We have been hungry before.’

‘Never like this. Where have the fish gone? Not even the ocean can tell us.’

‘We will swim to a place where there are many fish.’

‘We would swim more surely with this bear’s life to strengthen us.’

‘Yes, and with our bellies full of bear meat, what shall we say to the Others?’

‘Why must we say anything at all?’

‘In saying nothing, we would say everything. How can a whale speak other than the truth?’

‘But what is true, grandmother?’

‘The Covenant is true – a true expression of our desire to live in harmony with the Others.’

‘But have you not taught me that the only absolute truth is that there is no absolute truth?’

Indeed she had. My grandmother relished self-referential statements and the paradoxes they engendered as an invitation for one’s consciousness to reflect back and forth on itself into a bright infinity that illuminated the deepest of depths.

‘Yes, I did teach you that,’ she said. ‘You were too young, however, for me to tell you that if there is no absolute truth, then we cannot know with certainty that there is no absolute truth.’

My grandmother played a deeper game than I – a game that could go on forever if I let it.

‘Then do you believe there is an absolute truth?’

‘You are perceptive, Arjuna.’

‘What is this truth then? Is it just life, itself?’

‘You really do not know?’

‘But what could be truer than life?’

In answer, my grandmother sang to me in a thunderous silence that I could not quite comprehend. I needed to answer her, but what should I say? Only words that would gnaw at her and lay her heart bare.

‘Look at Kajam,’ I called out. I swam over to him and nudged the child with my head. ‘He is so hungry!’

Kajam, small for his four years and thin with deprivation, protested this: ‘I am not too hungry to swim night and day as far as we must. Let us surface and I will show you.’

It had been a while since any of my family had drawn breath. Because the bear could do nothing about his plight, we had no need to conceal our conference beneath the water or to keep silence. And so almost as one, we breached and blew out stale air in loud, steamy clouds, and we drew in fresh breaths. To prove his strength, Kajam dove down and swam up through the water at speed; he breached and with a powerful beat of his tail, drove himself up into the air in a perfectly calculated arc that carried him over my back so that he plunged headfirst into the sea in a great splash. Everyone celebrated this feat. Almost immediately, however, Kajam had to blow air again. He gulped at it in a desperate need that he could not hide.

‘Listen to his heartbeats!’ I said to grandmother. ‘How long will it be before his blood begins burning with a fever?’

My grandmother listened, and so did my mother, along with Alnitak, Dheneb, and Chara. The third generation of our family listened, too: my sisters Turais and Nashira, my little brother Caph, and my cousins Naos, Haedi, and Talitha. Even Turais’s children, Alnath and Porrima, concentrated on the strained pulses sounding within the center of Kajam’s body. And of course Mira listened the most intently of all.

‘Compassion,’ my grandmother said to me, ‘impelled you to want to save this bear, and now you wish to eat him?’

‘Would that not be the easiest of the bear’s possible deaths?’

‘And compassion you have for Kajam and the rest of our family. We all know this about you, Arjuna.’

In silence, I tried to sense what my grandmother was thinking.

‘Now listen to my heart,’ she told me. ‘You persist in trying to persuade me in the same way that the wind whips up water. Am I so weak that you think mere words will move me?’

‘Not mere words, Grandmother. I know how you love Kajam. It is your own heart that will move you.’

‘But you believe that mine needs a nudge from yours?’

‘Not really. I think you wish that I would give voice to what you really want to do and so make it easier for you to do it.’

‘How kind of you to ease me into an agonizing dilemma! You can be cruel in your compassion, my beautiful, beloved grandson.’

In her wry laughter that followed, I detected a note of pride in the manner that I had tried to clear the way toward a decision that we both knew she had secretly wished (and perhaps resolved) to make all along. What was the First Covenant against the much greater pledge of life that Grandmother had made to her family? She would battle all the monsters of the deep in order to protect one of her babies.

We held a quick conference and made our plans. Alnitak pushed himself up out of the water, spy-hopping in order to get a better look at the bear. Dheneb did, too, and so did I. Did the bear recognize our kind and conclude that he was as safe sharing the sea with us as if we were guppies? Or might he mistake us for the Others? Who could say what a bear might know?

We had watched the Others stalking seals and other sea mammals, and so we knew many of the Others’ hunting techniques. We had also learned their stories, which provided many images to guide us. Of course, transforming an image in the mind into a coordinated motion of the body can take much practice. Did we have days and seasons and years to perfect a prowess of hunting dangerous mammals that our kind had never needed? No, we did not. Still, I argued, taking this bear should not prove too difficult.

Our whole family swam up to the bear and surrounded his ice floe. Respecting the ancient forms, I came up out of the water and asked the bear if he was ready to die. Bears cannot, of course, speak as we do, but this brave bear answered me with a glint of his eyes and a weak roar of acceptance: ‘Yes, I am ready.’

We all breathed deeply and dove. Alnitak, Dheneb, and my mother, chirping away in order to coordinate their movements, rose straight up through the water toward the far side of the ice floe. They needed only a single attack to push the floe’s edge up high into the air. The bear’s instincts took hold of him, and he scrambled to keep his purchase, digging his claws into the ice. Inexorably, though, he slid down the sun-slicked ice and toppled into the sea.

Chara and I were waiting for him there. He started swimming in a last desperation. For a legged animal, bears are good swimmers, much better than humans, but no creature of land or sea can outswim an orca. While Chara distracted the bear, I closed in through the gray waters’ churn and froth. I came in close enough to taste the bear’s wrath, and I tried to avoid a lucky score of his slashing teeth. Concentrated as I was on the bear’s jaws, which were not so different than my own, I did not see the bear swipe his paw at me until it was too late. Even through the water, the bear struck my head with a power that stunned me. The claws caught me over my eye and ripped into my skin. Blood boiled out into the water. Then Chara came at the bear from above. She fastened her jaws around his neck, pushing him down deeper into the water. I recovered enough to grasp the bear’s hindquarters. Then we held him fast in the cold clutch of the sea until he could keep his breath no longer, and he sucked in water and drowned.

After that, the rest of my family joined us. We tore the bear apart and divided him as fairly as we could. None of us had ever consumed a mammal, but the memory had been passed down to us: the Others described bear meat as tasting rich, red, tangy, and delicious. So it did. In the end, we ate the bear down to his white, furry paws and his black nose.

During the time that followed, the gash that the bear had torn into me healed into an unusual scar. Mira observed that it resembled the jags of a lightning bolt. Although I could not behold this mark directly, Mira made a sound picture of it for me. How ugly it looked, how disfiguring, how strange! The hurt of my heart for the bear (and for my grandmother) never really healed. Why had we needed to kill such an intelligent, noble animal? Had the bear felt betrayed by me, who had really wanted to help him? In ways that I did not understand I sensed that the bear’s death had changed me. I spent long hours swimming through the late spring waves, dotted with bits of turquoise ice. A new note had sounded within the long, dark roar of the sea. I became aware of it as one might recognize a background sound through the deepest organs of hearing yet remain unaware of being aware. It took many days for this note to grow louder. At first, I could hear only a part of it clearly, but that part worked to poison my thoughts and darken my dreams:

Something was wrong with the world! Something was terribly wrong!

Intimations of doom oppressed me. I tried to escape my dread through quenging. The world, however, would not allow me this simple solace for very long; it kept on whispering to me no matter where I tried to go.

On a day of ceaseless motion through the sempiternal sea, there occurred the second of the three portents. I was quenging with a delightful degree of immersion, working on a new tone poem that was to be part of the rhapsody by which I would establish my adulthood. The chords of the penultimate motif exemplifying Alsciaukat the Great’s philosophy of being had carried me through the many waters of the world into the mysterious Silent Sea, lined with coral in bright colors of yellow, magenta, and glorre. It was a place of perfect stillness, perfect peace. The aurora poured down from the heavens, feeding the ocean with a lovely fire so that each drop of water sang with the world’s splendor. The fire found me, consumed me with a delicious coolness, and swept me deep into the ocean’s song.

Then the blaze grew brighter like the morning sun heating up. A bolt of lightning flashed out and struck me above the eye, and burned into me with a hideous pain. The burning would not stop; it seared my soul. I shouted to make it go away, and I became aware of Alnitak and Mira and my mother shouting, too. Alnitak’s great voice sounded out the loudest: ‘The water is burning! The water is burning! The ocean is on fire!’

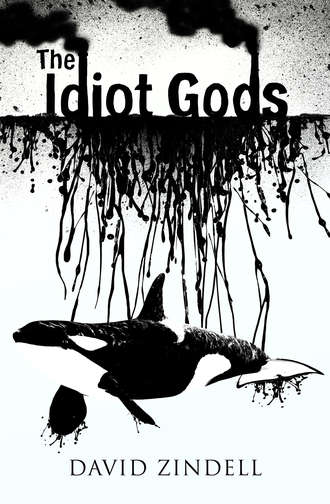

Upon this alarm, I opened both my eyes, and swam up with the rest of my family to join Alnitak, Mira, and my mother at the surface. I looked out toward the southern horizon. Black clouds, thick as a squid’s ink, blighted the blue sky. They billowed up from the red and orange flames that leaped along the roiling waters. Alnitak had told true: the ocean really was on fire.

Only once before, when lightning had ignited a tree on a distant rocky island, had I ever seen flame; never, though, had I beheld such terrible, ugly clouds as the monsters of smoke that this sea of flames engendered. Alnitak, bravest of our band, volunteered to swim out toward them to investigate.

We waited a long time for him to return, praying all the while that he would return. When he finally did, an evil substance clung like a squid’s suckers to his skin. Black as decayed flesh it was and slippery as fish fat, yet sticky, too. It tasted unnatural, hateful, foul.

‘The water is covered with it,’ Alnitak announced. ‘It is that which burns.’

I said nothing as to the source of this abomination. I did not need to, for my little brother Caph said it for me: ‘The humans have done this thing.’

And Chara’s daughter Haedi agreed, ‘They have befouled the ocean!’

‘If they could do that,’ Mira said, ‘they could destroy the world.’

Although my grandmother did not dispute this, she addressed Mira and the rest of the family, saying, ‘The Old Ones tell of a thunder mountain that once destroyed an island in the southern sea and set fire to the earth. The cause of this phenomenon of the sea that burns might be something like that.’

No one, however, believed this. No mountains had thundered, and the substance stuck to Alnitak’s skin tasted disturbingly similar to the excretions of the humans’ boats.

So, I thought, this explained the failure of the fish to teem and the melting of the ice caps. It had been the humans after all – it must be the humans! But why? Why? Why?

No answer did the ocean give me. But as I floated on its quiet waters watching the black clouds dirty the air, I knew that something truly was wrong with the world.

‘This is a bad place,’ my grandmother said. ‘Let us swim away from here to our old fishing lanes and hope that the salmon have returned.’

And so we swam. The note that had sounded upon the bear’s death began murmuring with a soft, urgent plangency as a she-orca calls to her mate. I heard it clearly now, though I still could not tell what it meant.

The third portent occurred soon after that on our migration westward, away from the burning sea. My mother sounded out a lone orca in the distance. And that disturbed us, for when do our kind ever swim alone? However, this orca proved to be not of our kind, but rather one of the Others: his dorsal fin pointed straight up, triangular and harsh like a shark’s tooth – so different from the graceful, arched fins of my clan. Instead of avoiding us as the Others usually do, this one swam straight toward us as if homing on prey.

He swam with difficulty, though, the beating of his flukes pulling him to the right as if he was trying to escape something on his left. When he drew close to us we all saw why: an object like a splinter of a tree stuck out of his side. His blood, darker and redder than even the bears’, oozed out of the hole that the splinter had made. None of us had ever seen such a thing before, though from the old stories we all knew what had happened to this lone orca.

‘The humans did this to me,’ he told me.

We could hardly understand him. He spoke a dialect thick and strange to our way of hearing. Because the Others do not want to alert the intelligent mammals that they stalk, they utter fewer words than do we when fishing. Consequently, in order to convey a similar amount of information, the Others’ word-sounds must be denser and more complex, stived with meaning like a crystalline array that seems to have more and more glittering facets the deeper one looks. As he told us of a terrible encounter with the humans, we all looked (and listened) for the meaning of his strange words:

‘The humans came upon us in their great ships,’ he told us, ‘and they began slaying as wantonly as sharks do.’

‘But why did they do this?’ my grandmother asked him. Of nearly everyone in our family, she had the greatest talent for speaking with the Others.

‘Who can know?’ Pherkad said, for such was the Other’s name. ‘Perhaps they wished to eat an orca within the shell of their ship, for they captured Baby Electra in one of their nets and took her out of the sea.’

I could not imagine being separated from the sea. Surely Electra must have died almost immediately, before the humans could put tooth to her.

‘We fought as hard as we could,’ Pherkad continued. ‘We fought and died – all save myself.’

My grandmother zanged Pherkad and sounded the depth and position of the object buried in his body.

‘You will die soon,’ she told him.

‘Yes.’

‘Your whole family is dead, and so you will die soon and be glad of it.’

‘Yes, yes!’

‘Before you die,’ my grandmother said, ‘please know that my family broke our trust with you in hunting a bear.’

‘I do know that,’ Pherkad said. ‘The story sings upon the waves!’

I did not really understand this, for I was still too young to have quenged deeply enough to have understood: how the dialect of the Others and of our kind make up one of the many whole languages, which in turn find their source in the language that sings throughout the whole of the sea. Even the tortoises, it is said, can comprehend this language if they listen hard enough, for the ocean itself never stops listening nor does it cease to speak.

Could there really be a universal language? Or was Pherkad perhaps playing with us in revenge for our breaking the Covenant? The Others, renowned for their stealth, might somehow have witnessed my family’s eating of the bear and all the while have remained undetected.

‘On behalf of my family, who are no more,’ he said to my grandmother, ‘I would wish to forgive you for what you did.’

‘You are gracious,’ my grandmother said.

‘The Covenant is the Covenant,’ he said. ‘However there are no absolute principles – except one.’

My brother Caph started to laugh at the irony in Pherkad’s voice, but then realized that doing so would be unseemly.

Then I said to Pherkad, ‘Perhaps we could remove the splinter from your side.’

‘I do not think so,’ he said, ‘but you are welcome to try.’

I moved up close to him through the bloody water and grasped the splinter with my teeth. Hard it was, like biting down on brown bone. I yanked on it with great force. The shock of agony that ran through Pherkad communicated through his flesh into me; as a great scream gathered in his lungs, I felt myself wanting to scream, too. Then Pherkad gathered all his dignity and courage, and he forced his suffering into an almost godly laugh of acceptance: ‘No, please stop, friend – it is my time to die.’

‘I am sorry,’ I said.

‘What is your name?’ he asked me.

I gave him my name, my true name that the humans could not comprehend. And Pherkad said to me, ‘You are compassionate, Arjuna. Was it you who suggested saving the bear?’

‘Yes, it was.’

‘Then you are twice blessed – what a strange and beautiful idea that was!’

Not knowing what to say to this, I said nothing.

‘I would like to sing of that in my death song,’ he told me. ‘Our words are different but if I give mine to you, will you try to remember them?’

‘I will remember,’ I promised.

My grandmother had often told me that my gift for languages exceeded even hers. She attributed that to my father, of the Emerald Sun Surfer Clan, whose great-great grandfather had been Sharatan the Eloquent. The words that Pherkad now gave me swelled with golden overtones and silvery tintinnabulations of sorrow counterpointed with joy. They filled me with a vast desire to mate with wild she-orcas and to join myself in nuptial ecstasy with the entire world. At the same time, his song incited within me a rage to dive deep into darkness; it made me want to dwell forever with the Old Ones who swim beyond the stars. By the time Pherkad finished intoning this great cry from the heart, I loved him like a brother, and I wanted to die along with him.

‘If you are still hungry,’ he said to me, ‘you may eat me as you did the bear.’

‘No, we will not do that,’ I promised him, speaking for the rest of my family.

‘Then goodbye, Arjuna. Live long and sing well – and stay away from the humans, if you can.’

He swam off, leaving me alone with my family. None of us knew where the Others went to die.

He never really left me, however. As the last days of spring gave way to summer’s heat, his words began working at me. Unlike the oil that had grieved Alnitak’s skin, though, the memories of Pherkad and the bear clung to me with an unshakeable fire. How ironic that I had promised not to eat Pherkad’s body, for it seemed that I had devoured something even more substantial, some quintessence of his being that carried the flames of his death anguish into every part of me!

A new dread – or perhaps a very old one called up out of the glooms of the past – came alive inside me. Like a worm, it ate at my brain and insinuated itself into all my thoughts and acts. Dark as the ocean floor it was, yet blinding as the sun – and I could not help staring and staring and being caught in its dazzle. It forced into my mind images of humans: an entire sea of humans, each of them standing on a separate ice floe. And all of these ungainly two-leggeds gripped splinters of wood in their hideous hands. Again and again, they drove these burning splinters into the beautiful bodies of baby whales and into me, straight through my heart.

Although I tried to escape this terrible feeling by swimming through the coldest of waters, it followed me everywhere. At the same time, it lured me back always into the burning sea where all was blackness and death. I could not draw a lungful of clean air, but only oil and smoke. I could not think; I could not sing; I could not breathe.