Полная версия

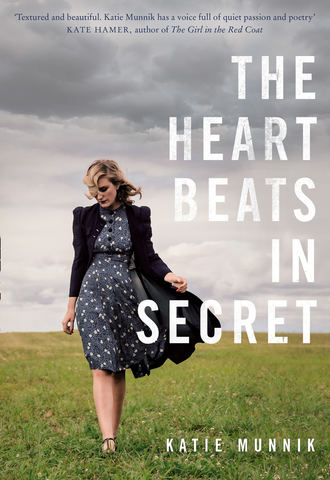

The Heart Beats in Secret

Lots of love,

Felicity

* * *

Montreal, March 1969

Dear Mum and Dad,

So much for nonchalance. Even if I didn’t have to, I’d want to leave my job now. Not because I’m tired out – though I am – and not at all because of the people, because they really are lovely. But the work is getting scary and so is this precarious city. You probably don’t hear much on the BBC, so here’s the scuttlebutt, as Dad would say.

Last night, there was hell of a march. The anglo press is reporting it as a peaceful protest, but at the hospital, we see another side to things. Of course, they are comparing it to last month’s attack at the stock exchange. No bombs last night, so no structural damage, but there were ten thousand people out on the streets, at least. From what we saw, the police got rough, or possibly the protestors did first. I was in the flat and there was so much noise outside. Someone lit a bonfire in the middle of the street like we were in a war zone or revolutionary Paris, and there were firecrackers or worse, too. Some were even shouting ‘A bas la Bastille!’ but it wasn’t the prisons they were protesting about or even the government. It was McGill. For heaven’s sake, a university. But a symbol, too. Everything is becoming a symbol, or a slogan. ‘McGill au Travailleurs!’ they chanted. ‘McGill Français!’ They’re demanding that the university become a unilingual French, pro-worker institution. So much for art history and politics if that happens, though I suspect nursing would still get funded. They’d need it.

At the hospital in the morning, we saw a lot of bruising, twisted ankles, and more than a few broken legs, too. One boy, who was carried in dangling between two cronies, came in with a fractured skull. They were all grinning, which was perhaps the most disturbing part. ‘Had a good night, boys?’ one of the doctors asked, but they only whispered to each other in French and kept on grinning.

One of the students who had been demonstrating came by the flat this evening, and got angry when I told him what I’d seen at work. He’s half French and mostly fervently separatist, but he likes hanging out with us British girls. I made a pot of tea and he told me about his grandmother – mémé. She had a digestive problem and it turned out to be cancer in the end and he spent a lot of time in the hospital with her, translating. Officially, everyone is guaranteed medical care in their own language, but he said it’s never really that way. His mémé needed a specialist, but the specialist didn’t speak a word of French and neither did half the nurses. Not like you, he said. You try at least. ‘Bonjour’ alone works wonders. He told me his mémé went downhill pretty quickly after she was admitted. He couldn’t be with her all the time and she spent her final weeks fumbling through the few English words she knew, trying to make herself understood by the busy anglo nurses. That’s no way to go, is it?

I see the injustice, but it’s all getting scary. There were four bombs on New Year’s Eve then three mailboxes exploded in the next few days. And those are the ones that get reported because they’ve exploded. I wonder how many other bombs have been found and stopped in time. Two exploded at the end of November at Eaton’s downtown. Even Jenny is getting apprehensive. She’s talking about heading out of town for a bit. I might try to convince her to come out to the camp with me. I called them the other day and the woman on the phone was lovely. No trouble at all, she said; come as soon as you like. There is a space where I can stay, and she wanted to know if the father was coming, too. A gracious way of asking. I told her that he wasn’t and she really gently suggested that I talk to him. Tell him where I was going. Give him the option, she said, so he could know and choose for himself. I don’t know. I’d rather do all this on my own. It isn’t like he’s going to turn around and ask me to marry him. He’s not that type. But he knows about the baby, so maybe I should talk to him before I go.

I’ve been having weird dreams, which isn’t surprising. I dreamed the baby was stuck in a postbox and I couldn’t get it out. When I looked down through the slat, I could see it all curled up on top of the letters like it was floating, way down at the bottom of a well. Then I dreamed that the baby was a package and I was wrapping it up with paper and string and worrying about the postage. What does it cost to post a baby? The woman at the post office was being difficult, and then, when I finally had it all wrapped and stamped, I realized I didn’t know how to address it. Isn’t that odd?

I hope this letter gets through – well, gets out of Montreal, I mean. I keep thinking about all those letterboxes. Sorry this is all so disjointed and rambling. That’s just how I’m feeling myself. I hope you are well. Thanks for the description of Aberlady Bay. It’s nice to think about things continuing on just as they always have – the wild flowers, the rabbits and the deer.

Lots of love,

Felicity

* * *

Montreal, April 1969

Dear Mum and Dad,

I will be moving soon. Yesterday, I went to the campus with Margaret to talk with some of her friends about the camp – they looked like a bunch of radicals with long hair and jeans, but they were kind. One of them had lived at the camp last summer and the other – Annie – was friends with the folk who started it up. She says she goes back and forth a lot to help them out. I asked if it was a cult or anything, but both girls said no. Annie said the folks who started it were Christians and there are some hippies now, too. Some folk are radical, but not everyone. It’s a real mix and it’s just a good place to be.

She showed me photos of the farmhouse where the midwife lives. Just a humble log house, really Canadian with a porch along the front, and a swing and gardens, too. They grow lots of food, and anyone who wants to can share in the meals. It’s about three hours away from Montreal, which sounds good to me.

Margaret’s going to be moving, too. Not far, but also to somewhere pretty different. She’ll be out along the St Lawrence Seaway in one of the new villages, living in her grandmother’s old house. When the province flooded the Long Sault Rapids ten years ago and the Seaway went through, whole villages were abandoned and people relocated, but some houses were moved instead. Margaret’s grandmother’s house was one of those – picked up and planted in a new village made from old homes. The Hydro Company promised the process would be gentle and everything would be safe. Even said they could leave the kitchen cupboards as they were, with all the plates and bowls still inside. It was that easy. The Hartshorne House Mover would arrive on the Thursday. All the family needed to do was pack a change of clothes and wait a day or two for their house to be delivered to New Town 2 where it would be built on a new foundation supplied by the Hydro Company. Safe and sound. Her grandmother worried – she hadn’t cradled the family china all the way from Ireland thirty years before to be smashed up by a machine now. But her grandfather took the company at their word. Even filled a teacup and left it on the kitchen table to see what would happen. That was Tuesday. But when the Hydro men came by on Wednesday and cut all the elms behind the house, he stood on the porch and cried. Margaret’s grandmother knew then that everything was changing.

Last winter, she passed away after eight years on her own. Margaret said that neither of them really felt settled after the move. They’d talked of moving to the city to be near their sons, but never got around to it. Margaret’s glad because it’s nice to have a family house to return to.

It would make me dizzy, I think. A house you know in a strange new place with different views out of the windows and a different piece of sky overhead. Margaret told me that when she was small, she used to help her grandmother dig potatoes in the garden behind the summer kitchen and they stored them for the winter in a dry root cellar with a red trapdoor. Now, the garden and the cellar are both under the river, but Margaret says she doesn’t mind. She told me she likes walking along the new shore. Everything still there, she says, but also washed away. You can see where the old highway runs right into the water. And Dad, it’s not far from your whales – only 10 miles or so. I suppose if there were more bones still buried, then the waters have covered them again. Margaret says where there used to be hills, now there are islands and if I go for a visit, she’ll take me out in a canoe to see. But that will have to wait until after the baby.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.