Полная версия

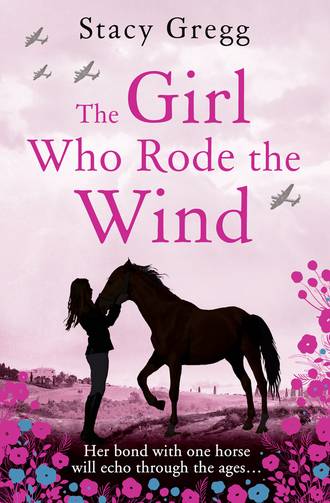

The Girl Who Rode the Wind

I would have done anything to find another seat. Jake was in all my classes, but we’d never spoken, not once. Due to my terminal uncoolness I guess.

I excused my lateness to Miss Gilmore, flung myself down into my seat and opened my textbook as she began writing up stuff on the white board.

Jake was looking at me funny.

“Hey!” he hissed.

I ignored him.

“Hey, Campione!”

I looked up. “Yeah?”

“Where’s your horse?”

There was laughter from Tori and Jessa who sat in the row behind us.

“Hey, Campione!” Jake leaned over towards me. “You know you smell of manure, right?”

I looked down at my boots. They were dirty from the stables I guess, but I hadn’t really noticed. I would have changed them if I had time. Anyway, there was nothing I could do about it now. I pretended I hadn’t heard him and began furiously copying down the lesson from the board.

Then suddenly, in front of everyone, Jake flung himself across his desk and began convulsing, coughing and spluttering like he was going to die or something. The whole class was watching him and Miss Gilmore stopped writing on the board.

“Are you all right, Jake?” she asked, looking concerned.

Jake stopped performing and sat up.

“Sorry, miss,” he smirked. “It’s like I can hardly breathe in here because of Campione! She stinks of horse poo!”

The whole class fell apart laughing at this and Jake gave me a look of satisfaction. His humiliation of me was complete.

I thought it would end there, but it didn’t. At lunch he gave a whinny as he walked by me in the cafeteria and made a big deal of holding his nose. I could see him at his table with the other populars, all of them looking over and laughing about it.

I walked home that day and for the first time ever I couldn’t wait to get out of my riding boots.

I didn’t want to talk about it, but Nonna has a way of winkling things out of you. She could tell something was wrong and that night after dinner she sat down on my bed and we had a big talk.

“He’ll have forgotten you by tomorrow, you’ll see,” my nonna said. “With a bully, you have to ignore them, like you don’t care. Then this boy will give up and start on someone else.”

“I am!” I insisted.

I kept on ignoring him, just like Nonna told me. But it didn’t stop. The next day Jake managed to get the seat next to me again and spent the whole class whinnying at me, doing it under his breath, just quiet enough so the teacher couldn’t catch him. He did the same thing in the playground every time he walked past me, and by the end of the week all the other kids were doing it too.

“Do you want me to talk to one of your teachers about it?” Nonna offered.

“No!” I was horrified. “No, honest, I’m fine. Just forget about it …”

I stopped talking about Jake at home. I was worried that Nonna would tell Dad and then the next thing I knew he’d be marching into school to “sort him out”. I was desperate to avoid this happening – almost as desperate as I was for Jake to stop picking on me.

Dad worried about me in a way he’d never done with Johnny and Vincent, or even Donna. She had been a popular when she was at school. Now she was studying to be a beauty therapist, which accounted for the fact that she spent all her time at home practising her make-up in the mirror and painting her nails. We shared a closet – half each. Her half was overflowing. My half was all T-shirts and jeans.

“Can I try on one of your skirts?” I asked Donna.

“Why?” she looked suspicious.

“Because.”

“As long as you don’t ruin it.”

I pulled out her blue skirt with the black spots.

“Can I wear this to school?” I asked.

“Since when do you wear skirts?” Donna arched her over-pencilled brow at me.

“Please, Donna?” I went red in the face.

“OK,” she sighed. “I don’t like that one anyway – you can have it.”

I tried it on.

“It feels strange to have bare legs,” I said.

“You have lovely legs,” Nonna said.

“She has legs like hairy toothpicks!” Donna shot back.

“Donna, be nice to your sister!” Nonna Loretta warned.

“You need some shoes to wear with it,” Donna pointed out.

I looked at myself in the mirror.

“All the populars wear white trainers,” I said.

“Trainers?” Nonna asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “Like white sports shoes.”

I looked at the shoes in my half of the closet.

“I can wear these I suppose.” I fished out my usual shoes – a pair of battered old red Converse and put them beside the skirt in my half of the closet.

The next morning, when I got home from helping Dad at the track, Nonna Loretta was waiting for me. She’d made me lunch and there was a box beside it on the kitchen table.

“What’s in the box?” I asked.

“Take a look,” she said.

They were white tennis shoes.

“I got them in a sports store on special,” Nonna told me. “That’s what they wear at school, yes?”

“They’re not the same,” I said. “These are tennis shoes.”

Nonna didn’t see the difference. “Try them on.”

They fitted me.

“There! They look very nice,” Nonna said.

On Monday I wore my new outfit to school. The skirt was a bit big so I put a belt on it. The shoes were so white they positively glared in the sunlight. I had English first period. I made sure I was early and got my usual seat at the front, but on the way out of class Jake caught up with me.

“Hey, Lola. Cool shoes.”

I felt sick. He was being totally sarcastic.

How could I have been so dumb? The shoes were totally wrong! I wished I could have just taken them off and walked around in bare feet, but that wasn’t allowed at school.

At lunchtime, I decided the best thing to do was go to the library so that no one would see my dumb white shoes. I was on my way across the playground when Jake spotted me. He was with Ty and Tori and Jessa. They began to walk towards me. There should have been a teacher on duty, but I couldn’t see one.

“Hey, Campione!” Jake cocked his head so that his hair flopped to one side then he pushed it back coolly with his right hand. It was his trademark gesture, like he thought he was in a boy band. He was so vain about that hair; you could tell he spent hours on it each morning before school. It was shaved short up the back and the fringe was long so that it grazed perfectly against his tanned cheekbones.

“Where’d you get your shoes?”

I kept my eyes down. I tried to keep walking past him, but he stepped in front of me and blocked my way.

I stepped to the left and Jake did too. Then to the right, and he matched me, like we were dancing. I could feel my face burning with embarrassment.

Jake stepped in real close to me and then he gave an exaggerated sniff, wrinkling up his nose.

“You might want to change those shoes again, Campione.” He grinned. “Because you still stink of horse poo!”

I heard the laughter buzzing in my ears and saw the smug look on Jake’s face. And that was when I threw the punch that broke his stupid nose.

Dad broke eleven bones in his racing career. You could see how his collarbone stuck out funny from the time when a horse went up on its hind legs in the starting gate and crushed him against the barrier. Another time he spent a week in intensive care after a three-year-old he was breezing spooked at a car horn. Dad fell and another horse running behind him struck him with a hoof on the head, shattering his helmet into pieces and knocking him out cold.

He fit right in with the other jockeys in the bodega, sitting around shirtless, comparing battle scars as they drank endless cups of black coffee. Most of them were on crazy diets to keep thin enough to make racing weight. Dad liked to “mess with their heads” by sitting right beside them at the communal dining table and ordering a big breakfast from Sherry who ran the kitchen – sausages, beans, eggs and fried bread. You should have seen the half-starved look on the jockeys’ faces as Dad sat there and ate his way through it all, groaning with pleasure and savouring every bite. He thought it was hilarious.

“I punished my body harder than any of them back in the day,” Dad would say. “Taking saunas for hours before a race to sweat out the water weight and drinking those disgusting diet shakes.” He would shake his head in disbelief. “Sometimes when I sat on a horse I was so weak from hunger I couldn’t even hold him back. No wonder I fell so many times.”

When I was little, instead of bedtime stories, I would get Dad to recount the tales behind all of his broken bones. He made a real drama out of it, acting out the whole race for me. He could recall every name of every single horse and its jockey, all the details of how he rode the race and where he was in the field at the moment he fell.

The best story by far was the one about the missing fourth finger on his left hand.

“The horse was called Forget-me-not,” Dad would begin. “And when I got given the ride on him, Lola, I was punching the air with the thrill of it! He was this big, black stallion, pure muscle and power, and he was the flat-out favourite in the Belmont Stakes. My cut of the purse would come to enough money to buy my own stables.”

He would be telling me this as he sat on the side of my bed and I would be propped up on my pillows beside him in my pyjamas, wide-eyed, waiting for the rest of it as if I had never heard it before, even though I’d been told the story a thousand times.

“Anyway,” Dad would continue, “the week before the race I’m breezing Forget-me-not, working him alongside a couple of other horses to get his blood up, when he gets crowded on the rail and panics, and I don’t know what gets into his head, but all of a sudden he tries to jump the barrier! He breaks the whole railing and I must have been knocked out cold, because the next thing I know they’re wheeling me into the hospital and I can feel this real sharp pain in my left hand. So they take me straight up to x-ray and the doctors take a look and it turns out my finger is broken in three places. Must have hit the rail as I went down.”

I look at the missing place where Dad’s finger used to be.

“So they cut it off?”

Dad shakes his head. “Not straight away. They tried strapping it up with tape, and said it just needed time to heal. But I had the Belmont the next week and that tape was no good. Even with a glove over the top I couldn’t close the finger and grip the reins without screaming in pain. So I went back, told the doctors I needed painkillers, but the drugs they gave me, all they did was make me woozy. So I went back to them again, and do you know what I said?”

I did know, because I had heard this story before. And not just from Dad. I’d heard it from the other jockeys in the bodega. In the version my dad told me, he walked into hospital and insisted they remove his finger so he could ride.

But the way the other jockeys told it was even more gruesome. They said the surgeons refused to amputate and so my dad went back to the stables and got a wood block and a splitter axe and cut the finger off himself. Then, with his hand wrapped in a gamgee horse bandage, he caught a cab back to Jamaica Hills, showed the doctors the bloodied stump and told them to go ahead and stitch it up.

Dad rode in the Belmont Stakes that weekend minus his finger. Forget-me-not came in dead last.

I’m telling you this because you need to know the sort of man my dad is. So now you’ll understand why I couldn’t bring myself to go home and admit to him I’d been suspended from school.

Fernando was sweeping out the aisle between the loose boxes when I reached the stables.

“Lola!” he gave me a friendly wave. “You lookin’ for Ray? He’s long gone.”

Dad finished working the last of the horses by midday. He’d have been up since four a.m. and he’d be home having his afternoon nap by now, just like I’d told Mr Azzaretti.

“I came to see the horses,” I said.

Fernando looked at his watch. “No school today?”

“I finished early.” This wasn’t exactly a lie. “Can I help muck out the stalls?”

Fernando leant against his broom. “Maybe you can take out Ginger? I was gonna put him in the walker. You can do it while I finish up here?”

“Sure,” I said.

In the tack room I threw down my backpack on a chair and gave it a sideways glance, thinking about that note, shoved down deep against my textbooks. Then I went over to the wall where all the halters were lined up and grabbed one.

Ginger had his head out over the door of the stall, waiting for me.

“Hey, Ginge.” I gave him an affectionate scratch on his muzzle, but he flinched away from me. He wasn’t very friendly. Most of the horses in Dad’s stables were grumpy, to tell the truth. Ginge was the worst of them all – he was a biter. Last week he had bitten Tony the groom’s finger when he went to slip on his halter, pretty much taking the skin clean off with his teeth. Dad said Tony had screamed like a girl – which I found insulting because I don’t scream.

Anyway, Tony should have known better because everyone knew you had to watch Ginge like a hawk when you were tacking him up. All I needed to do today to put him on the walker was put his halter on and lead him across the yard. The walker was this big circular machine – the horses went inside the cage and you turned the engine on and the walker kind of scooched them along from behind, so they had to keep going in circles, a bit like a playground roundabout, turning them round and round. It gave them exercise on days when there was no jockey to ride them.

I was about to slip the halter on when I had a much better idea.

“Fernando?”

I stuck my head around the corner of the loose box. “I’m gonna jog Ginge, OK?”

Fernando stopped digging at the straw. “You what? Since when are you riding track, Lola?”

“It’s OK,” I told him. “Dad said I could do workouts – not on Sonic and Snickers, but just with the horses that aren’t the big shots, like Ginge and Cally.”

I liked this lie. It sounded believable that Dad would let me ride the horses that were pretty much already failing as three-year-olds. The other day I’d heard him say that Tiger, our moggie cat, had more chance of winning the Preakness than Ginger did.

Fernando shrugged. “Easier to put him in the walker, but if you want to ride, kid, and your dad’s OK with it, you go right ahead.”

Ginge had his ears back the whole time as I tacked him up, looking real moody about it, as if he’d been having a nice quiet time before I interrupted his day. But once we were actually out from the stalls and on the track, he obviously felt differently. His ears pricked forward and with each stride he gave a quick, enthusiastic snort like he was humming a tune to himself.

I made him walk at first, until he got used to the sights and sounds. There was a ride-on mower trimming the infield, and he spooked a little as it went past so I had to reassure him. Ginge usually raced in blinkers because he was prone to spooking and being distracted. I let him have a good hard look at that ride-on and then I clucked him up to a trot.

Racehorses are like athletes. They have a workout programme devised just for them. One day they’ll be jogging, just trotting along to loosen up their muscles. The next day they’ll be breezing – going almost flat out at a gallop, but still not quite at racing speed. I’d told Fernando I was gonna jog, but by the time I reached the back straight, I decided it wouldn’t do any harm to try Ginge at a gallop.

I rocked up high in the saddle and put my legs on, asking him to go faster, and the trot became a canter. Ginge was snorting and huffing beneath me, and when I urged him on some more he reluctantly picked up the pace into a slow, loping gallop. That was Ginge all right. He’d never won a race and it drove Dad mad because he knew Ginge had speed in him. He was just stubborn about showing it.

“Come on, Ginge,” I coaxed him. “Let me see what you’ve got.”

Nothing. I was hustling him along, kicking and pumping my arms, but Ginge refused to go any faster.

We rode almost three furlongs like that and then, as we swept around the far side of the track, I heard this almighty crack. The ride-on mower had backfired. It sounded just like a gunshot and it put a shock through Ginge like a lightning bolt. He spooked violently and I felt him suddenly skitter out sideways from underneath me. For a sickening moment I thought I was gonna fall, but somehow I managed to stay with him and get my balance back. He was so strong against my hands, stretching out flat at a gallop. I don’t know what made me do it, but instead of trying to pull him back, I let him run. “Go on, then! Go!”

Ginge’s hooves pounded out like thunder against the soft loam, as I perched up there on his back, urging him to go faster and then a little more again until we were flying.

The wind was so strong in my face it stung my eyes. I had tears streaming down my cheeks, and even though they weren’t real ones, it felt so good to cry. I was racing the wind and everything that had happened that day got left behind in my wake and I was myself again and I was free.

Back around by the exit to the stables I pulled Ginge up at last and brought him back to a jog. He was blowing so hard that I had to do another whole lap of the track at a walk to cool him down, and then I leapt down and led him back to the stables.

“That didn’t look like no jog to me.” Fernando glared at me as I brought Ginge through to his stall. “This horse has to race on the weekend, you better not be messing with his training.”

I shook my head. “Sorry, Fernando, I tried to pull him up, but he took off on me and I couldn’t hold him.”

Fernando looked at me with an air of resignation. “You think I’m a fool, Lola? I know what you were doin’ out there.”

He took Ginger’s reins and I thought he was in a bad mood with me until he cast a look back over his shoulder and smiled. “You ride track real good. You look just like Ray out there.”

Just like my dad.

That was all I ever wanted to be.

My brother Johnny glared at the spaghetti on his plate. “C’mon. Are you kidding me?”

“What’s your problem now?” Dad asked.

Johnny poked at it with his fork. “Is that all I get? Where’s the rest of it?”

“It’s enough.” My dad ignored his complaint and carried on dishing up meatballs to the rest of us. “You know the deal. You want to ride track, you gotta watch your diet.”

“I do!” Johnny insisted.

“Sure,” my dad grunted. “So that must be why I saw you at Dunkin’ Donuts on the way home after workouts this morning.”

Vincent gave a hoot of delight. “Busted!”

“Yeah, laugh it up, brother!” Johnny jabbed his fork at him.

I kept cutting into my meatball.

“You’re very quiet this evening, Lola,” Dad said.

“I’m hungry, that’s all,” I said.

I was hoping he wouldn’t ask me about school because if he asked me straight up then I would have to confess that I had been suspended. That note from Mr Azzaretti was still there, glowing out at me like neon from my school bag in the corner of the room.

My dad cast a glance at Nonna, as if she might have an insight as to why I was so silent, but she gave a shrug as if to say she had no idea and so Dad let it drop.

“Loretta.” He cleared his throat. “You remember that Ace of Diamonds filly that Frankie was training last season?”

Nonna nodded. “You mean the bay with the white socks on the hind legs?”

“That’s her,” my dad said. “Well, you always said you thought she had star quality. Frankie thought so too. He sent her off to Lance Barton’s stables in Kentucky and the word is she’s been breaking three-year-old records on the training track there in every single workout.”

“Is she ready to race?” Nonna asked.

My dad nodded. “This Thursday at Churchill Downs is her maiden. Frankie’s told me on the down-low that she’s a sure bet to win it. And the odds, Loretta.” My dad’s voice dropped to a low whisper. “She’s paying out at seventy-three to one.”

Nonna Loretta’s face fell.

“Absolutely not, Raymond!”

“Listen –” my dad began, but he was cut dead by Nonna.

“No, Ray, you listen to me! How many rules do we have in this family?”

There was silence around the table. None of us dared to speak when Nonna was in full flight like this.

“Two rules, Ray!” Nonna sure had a powerful voice for a little old lady. “Two rules that the Campiones live by. We don’t bet on horses and we don’t tell lies.”

I felt myself curl up a little, trying to make myself smaller as she said this.

“But, Loretta!” My dad bounced back. “This horse, she’s a machine. She’s gonna win by ten lengths and nobody will ever see it coming! And seventy-three to one! Maybe even more. The bookies will –”

“The bookies will take your money because that’s what bookies do,” Nonna Loretta said stonily.

My dad took a deep breath. “I’m telling you …”

“No, Ray,” Nonna said. “I’m telling you. The racing business is how we make our money, but betting on races is different. That’s a sure-fire way of losing the lot. We’ve made it this far without betting on horses, haven’t we?”

My dad sighed. “All right, all right. I thought, just this once …”

Nonna’s scowl deepened.

“OK,” Dad said. “I get it. No betting, period. OK?”

“Aww, c’mon,” Donna groaned. “Can’t he place just a little bet, Nonna? There are these new high heels that are on sale right now at Macy’s that I would love …”

Donna saw the look on Nonna Loretta’s face and shut her mouth real quick.

I didn’t say a word. I was just glad that the whole argument had taken the attention away from me and while they’d all been talking, I’d been busy cleaning my plate.

“May I be excused, please?” I asked.

“You’ve finished already?” Nonna raised an eyebrow.

“Sure, Lola,” Dad said. “Have you got homework tonight?”

“No,” I said truthfully. “No, I don’t.”

As I left the table I heard Nonna Loretta ask my dad, “So that filly Frankie tipped you off on. What’s her racing name?”

“Aces High,” my dad replied.

It was a good name, I thought. I don’t know much about playing poker but I’m pretty sure that aces high usually wins.

The next morning I said goodbye to Nonna and started walking to school. I took the usual cut-through at Sutter Street, clambering through the fence into the park. And that was where I stopped. I sat there on the swing set, rocking back and forth and thinking about what to do.

I had never told a lie like this before. The problem was, I had left it too long now to come clean and had made it worse. I got down off the swings and sat inside the playground’s plastic crawly tunnel for a bit, worried that I would get seen by someone if I stayed out in the open for too long. Then I realised I was acting ridiculous. I couldn’t turn up here every day and hide in a plastic tube. I had to tell the truth. I had to go and talk to Dad.

It was almost ten o’clock by the time I reached the track. Dad would have finished working the last of the horses by now. He would be back in his office doing the paperwork.

Dad called it an office, but really it was just a loose box like the ones the horses used, except with a desk and a filing cabinet in it, instead of straw on the floor.

I was walking past the stalls when I heard the sound of hoof beats behind me.

“Hey, Lola!”

It was Johnny and Vincent. They had just finished a workout; both their horses were sweating and blowing.

“I’ve got to see Dad,” I said, ignoring them and walking towards the office.

“I wouldn’t go in if I were you,” Vincent said.

I kept walking.

“Mr Azzaretti is in there.”