Полная версия

The Gentry: Stories of the English

The site chosen by Maria for this performance was the beautiful stone manor house at Corsley, three miles from Longleat. It and the lands around it formed the Thynnes’ dower manor, set aside for the use of the widow of the previous head of the family. Maria was imagining a future in which her vulgar, old, fat, widowed mother-in-law was ensconced at Corsley, squatting on the pastures for the good of the ground. It is as cruel an image as anything in these gentry stories, of a broken woman whose life was good for nothing but some droppings on her dead husband’s ancestral lands.

That takes some coming back from, but as time went by, Joan attempted to mend the breach. She arranged for a marriage of one of Thomas’s sisters to a Mr Whitney, who was remotely connected with the Audleys, ‘a gentleman of a very ancient and worshipful house, and an aliesman [a relative, allied by kinship] to your Lady’.83 If the marriage came off, she told Thomas, ‘it might renew a mutual love in every side to the comfort of many and besides his estate so great and his proffers so reasonable and well.’84 The old sense of class anxiety is never absent:

I credibly understand that all the lands whereof Mr Whitney is now seised was Whitney’s lands before the conquest of England; and that ever sithence it hath and doth continue in the name and blood of the Whitneys, but although himself be but an esquire, yet there were eighteen knights of his name before the Conquest which were lords and owners of the same lands which are now his.85

That can only have been received at Longleat with derision. Quite consistently Thomas Thynne refused to release lands or money for his sisters’ dowries, even though he had previously agreed to give them £1,000 each, engaging in endless correspondence with his mother on the subject and no doubt encouraged in his meanness towards them by his wife. Although Thomas was a Member of Parliament and had been knighted in 1603 in the great rush of honours that accompanied James I’s arrival on the throne, the romantic young man had by now turned into a slightly weak thirty-year-old. Maria’s family had him where they wanted him, telling him how to manage his timber in the park at Longleat86 and selling him their neighbouring manor of Warminster for a sum (£3,650) and on terms – the full amount payable within the year – which as Thynne said was ‘so unreasonably high a rate as no man would come near it’.87 The Mervyn–Audley gang were cashing in on the trick they had played so many years before at the Bell in Beaconsfield.

Maria’s mother, Lucy Audley, wrote her a letter about the deal in phrases which stink even 400 years later: ‘Well Mall’, she began, using the family nickname for her daughter,

I am exceeding glad that the iron is stricken being hot, for there is a time for all things, and sorry should I have been in both your behalfs, if it had now been omitted; and truth is I know it so great a grace to Longleat as if another had enjoyed it I should have rained tears upon Warminster whenever I had looked upon it. I was more confident that you would have dealt in it, as supposing that you know me a loving mother, and not a cunning shifter, to put a trick upon my son Thynne and yourself for serving any turn, and the truth is enough on that.88

The precise meaning of that last sentence may be a little clouded, but the intended import and the subtext are both radiantly clear: Would I ever cheat you, my darling girl, or your lovely husband? I only have your and Longleat’s best interests at heart. And underneath that, the inadvertently conveyed message: I am indeed a cunning shifter, which is why you are where you are, and I am now squeezing money out of you and Thomas in the way that I have always done to others.

And the fate of these families?

The Mervyns soon disappeared from history entirely. It was important to Sir James, the architect of much of the grief in this story, as to many gentry families, that his land and name should remain attached. He had no sons but he got round that by ensuring that his granddaughter Christine, Maria’s younger sister, was married to her cousin Sir Henry Mervyn. Connected to her by both genes and name, Sir James could leave her his beautiful Fonthill estate and other manors elsewhere in Wiltshire. But he was thwarted. As soon as Sir James died, Sir Henry starting selling off the inheritance, a large chunk of it including Fonthill to Christine’s brother Mervyn Touchet, Lord Audley and Earl of Castlehaven. In him the lunacy of the Touchets flowered expansively and he was beheaded in 1631 for sodomizing his servants and participating in the rape by those servants of both his wife and his twelve-year-old stepdaughter.89 After this hiccup, things were soon restored to something approaching normality and that family also persisted, if on a declining path, selling off Compton Bassett in the 1660s, until the last and 25th Lord Audley died in 1997. Fonthill ended up in the hands of the Beckfords and became the site of the eighteenth century’s most extravagant folly. In none of the Audleys did any attachment to Wiltshire land remain.

The Thynnes are one of the great success stories of the English gentry. Like the Cavendishes, the Spencers and the Cecils, the family escaped the vulnerabilities of a gentry existence and entered the realms of the higher – and richer – aristocracy. Longleat became the headquarters of an enormous and ever-growing estate, comprising thousands of acres in addition to the Shropshire lands brought to them by Joan Hayward and the Wiltshire manors they had bought from the Audleys. As Barons, Viscounts and finally Marquesses of Bath they persisted across the centuries in a way that few gentry families have ever managed.90

One of the ironies of this encounter between Mervyn greed and Thynne gullibility is that the Thynnes were the victors. But that is not the salient point: the key aspect of this story is the way in which its women – Lucy Audley, Joan Thynne and Maria Touchet – are its principal players. The entire dynamic of the three families is inexplicable without their sense of honour, ambition, propriety and threat. They are not merely – as women at this stage are so often portrayed – the default administrators of estates when their men are away. They are the setters, creators and maintainers of the family cultures which governed the internal relationships of the class. They are subtle and powerful, passionate and impassioned. No child could have been uninfluenced by these women, their mothers and their wives, and no history of the gentry can make sense without them.

PART III

The Great Century

1610–1710

The seventeenth century was the heartland of gentry culture. The sense of looming threat from grandees or the crown, or from people not admitted to the gentry’s own charmed circle, was – at least outside the great crisis of the 1640s and ’50s – surprisingly and wonderfully absent from their lives. England was constitutional and their own place in that constitution as Members of Parliament, Justices of the Peace and sheriffs of their counties, upholders of what seemed like an ancient tradition, was deeply self-confirming. Their letters and journals, the houses they built, the landscapes they created and the portraits they had painted all exude an atmosphere of arrival, of this being the great century in which to have been alive.

Many of the gentry were obsessively retrospective and this was one of the glory periods for false genealogies. The Cecils at Hatfield (Welsh sheep men in 1500) had a beautiful, illustrated pedigree drawn up that traced them back to Jesus and from there to Noah and Adam. But the time glittered with the kaleidoscope of modernity, a world we would all begin to recognize: fast food in London streets; shopping centres; newspapers; town squares; terraced houses; suburban villas; experimental science; botany; archaeology; the Stock Exchange; commercially available finance; mortgages; wood screws; microscopes and telescopes; the country house as a centre of culture and art; a professional navy; a private but coherent postal system; most of the hedged landscape; floated meadows; estate maps; landscape paintings; a national market in agricultural products and the end of self-sufficiency; a consciousness of England as the emporium of the world; the pervasive presence, at least in gentry houses, of global commodities, especially sugar; garden exotics (tulips, Persian fritillaries); the empire – Ireland as a trial run, the West Indies, Virginia, the Carolinas; eventually a constitutional monarchy; political parties; and liberty as the essence of Englishness.

‘Felicity’ was the word Edward Hyde, Lord Clarendon, the great Royalist politician-historian, used to describe this moment, when

this Kingdom, and all his Majesty’s Dominions enjoy’d the greatest Calm, and the fullest measure of Felicity, that any People in any Age, for so long time together, have been bless’d with; to the wonder and envy of all the other parts of Christendom.1

But this was no effortless glide into a pre-chewed future. It was not as if the usual constraints on existence were somehow suspended: the demands of family life, the inadequacy of pre-modern medicine, the unkindness of others. These, needless to say, impinged on all lives. Added to them was the larger context of ferocious political and religious argument, which coloured the entire century. England underwent two revolutions, two civil wars, and had two kings deposed. Right in the middle of the century it became a republic for the only time in its history, run by a politburo of military-religious men, with an all-pervasive informer network. Individuals lived in fear and private diaries from the time were slashed and razored by their authors to cut out any incriminating passages. That experience explains much of the following century, characterized by a hunger not for the fierce statement of metaphysical truths but for a kind of easy civility in which order and freedom could sit side by side.

The Civil War of the seventeenth century was fought by the gentry against the gentry. On one side were those who felt a conservative if at times reluctant loyalty to the king; on the other those who felt that the autocratic manner of the King’s government and its quasi-Catholic beliefs had betrayed them and the country which they owned and of which they were the bedrock. It was a war between the gentry’s belief in inherited order and its belief in its own significance as a governing class.

That war and its causes have loomed large in all modern discussions of the gentry. The brilliant and vituperative academic debate between a group of largely Oxford historians in the mid-twentieth century left the gentry itself a bruised battlefield, littered with the corpses of competing theories. Every one of those theories was hamstrung by the difficulty of identifying watertight socioeconomic groups which could be seen to be acting in singular and coherent ways. Any examined group tended to fragment into its individuals and to blur all possible definitions. In the aftermath of ‘The Storm over the Gentry’, historians have retreated from large-scale theorizing towards closer descriptions of individual families, the net of allegiances in the gentry world, the county communities, and the non-ideological and self-protective nature of much of gentry life. That is certainly the picture that emerges from the families which carry the seventeenth-century story here: one family, the Oxindens, spread across many social layers; another, the Oglanders, strongly constitutionalist but reluctantly needing to support the King; another, the le Neves, divided between its urban-mercantile connections and its rural-Tory inclinations; some, the Hobarts, Puritan-Parliamentary, in pursuit of power; others, the Gawdys, disengaged from the questions of politics, pursuing bluntly conservative lives.

It is certainly possible to be sidetracked by the glamour and tragedy of that war. Much of gentry life continued past and through it largely as if it had not happened. At the end of it, and at the Restoration of the crown in 1660, the gentry as a group were in pretty much the same economic and political position as they had been before, owning the same proportion of the country and as deeply engaged in parliamentary government as they had been a hundred years earlier. The revolution of 1688, when they expelled the last Stuart, a despised Roman Catholic, and brought in a satisfactorily Protestant Dutchman, William III, seemed like the apogee of their power. Government would be constitutional and the landowning class would control it.

But this triumph contained the seeds of its own decline. The end of the seventeenth century was difficult. The weather, which had also been atrocious in the 1640s, entered a bleak spell in the 1690s with a series of pitiably poor, starvation harvests. Revenues and rents from land began to be depressed. The growth in population slowed. On top of that, the new government that had come in with the Dutch William III was now militarizing fast. Between 1689 and 1714, the Royal Navy became the biggest in Europe. In 1692 a land tax was imposed at four shillings in the pound, a 20 per cent tax on gentry incomes. A government which had looked as if would be the embodiment of landholding England became instead the government of a combination of the Whig aristocrats, the commercial interests of the City of London and its growing Atlantic empire.

In the century to come, which would belong to the merchants and the great Whig oligarchs, the nature of the gentry began to divide into an old Tory world view and a new Whig one. If there is a hinge in gentry history, this is it. The Tory squires of the 1690s belonged to a world that was palpably continuous with the thought patterns of Sir William Plumpton and the old Throckmortons. After them, gentry culture conceived of itself, at least in part, as something that was out of kilter with modernity. That was one of the things the duel between Oliver le Neve and Sir Henry Hobart on Cawston Heath was about.

The squire was starting to become yesterday’s story. His belief in inherited virtue, in the whole idea of transmission from a semi-feudal past, was looking fragile in the face of the new ideas of educated virtue, of virtue to be acquired not by inheritance but by learning and good behaviour. ‘A man of polite imagination’, Joseph Addison wrote in the Spectator, enjoyed ‘a kind of property in everything he sees.’2 That is not what the landowners of Norfolk would have thought. They knew all about property but, for these voluble and scarcely polished squires, learning was something of a foreign country. It is true that Oliver le Neve owned a copy of John Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding, but it was a rare flower amidst a bookshelf filled with Peppa – A Novel, Muse’s Farewell to Popery, Britain’s Glory, Ladies’ Travels into Spain and The New Art of Brewing.

The squire was becoming a slightly laughable figure. The man of honour was slipping into the lovable, old-fashioned, uneducated Tory, who could not quite keep up with the badinage of the coffee house or the London club and who remained happily unaware that everyone around him was laughing at his accent, his clothes, his wig, his ideas, his whole marinaded, antiquated roast-beef self and his obsession with hunting and shooting.

Why so much about hunting? In part, it was inherited behaviour. The hunt was gentry communality, jointness, what they did, who they were, the sort of thing they had always been. As that, it was also an act of dominance, of lordliness, ownership, nostalgia, control and removal from the world of an earned living. It was a form of play-warfare in which the enemy was absent. It was also a stimulus to the blood, a source of adrenaline, the seventeenth-century substitute for a skiing holiday, an escape from the house, from the wifely ‘bridle’ – a term le Neve’s friends use – and the stir-craziness of being too long at home. ‘I am longing much for a little libberty,’ Sir Bassingbourne Gawdy confided to his brother-in-law le Neve in February 1698, when his father had been ill, ‘for I have bin A Prisoner this thre weeks or more.’3

I wonder if there wasn’t something else in play here too. These Tory squires, knowingly or not, were on a downward trend. The focus of value in England was moving away from land and land ownership towards an increasingly dynamic and urban market. The last decade in which any part of England remained self-sufficient and did not grow crops for sale, or derive its food from elsewhere, was the 1680s. The medieval vision of integrated, rural communities, each a ‘little commonwealth’ as the great Jacobean surveyor John Norden had called a manor, was now over.4 Throughout the seventeenth century rural rents had been dropping; London property was increasingly valuable.

But the world of hunting was the squire’s province. You could dragoon and whip a pack of beagles in a way that the electors of Norfolk would never allow. You could live a fantasy life when out with your friends all day on horseback in a kind of toy theatre and as a nostalgic dream of significance. When your credit (financial or otherwise) was looking thin or your tenants found it difficult to pay their rents, it may have been the only consolation there was.

1610s–1650s

Steadiness

The Oglanders

Nunwell, Isle of Wight

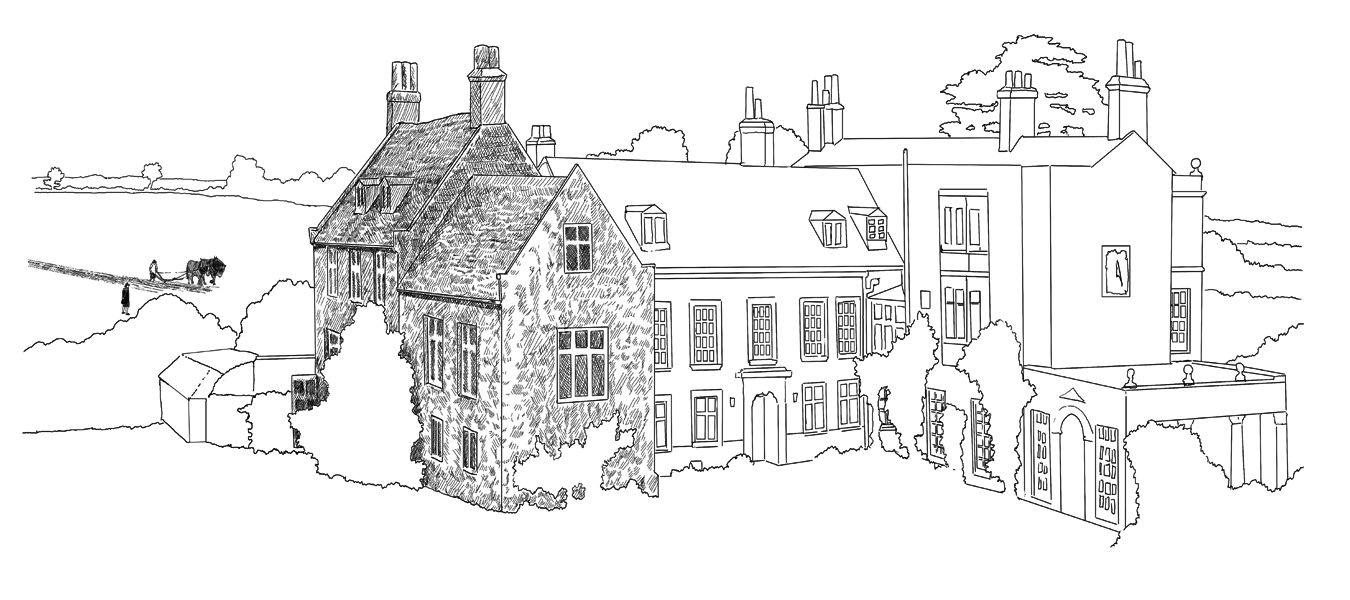

Sir John Oglander was in love with his own life: with his vision of the past and his long line of ancestors stretching back into it; with his own role as the guardian of his family’s wellbeing in the troubled seventeenth century and on into ‘futor Adges’; and with Nunwell, the Oglander house and lands at the eastern end of the Isle of Wight, the matrix of his being, to whose health and happiness he dedicated year after year.

His deep attachment to Nunwell and the Isle of Wight is intriguing because although he was born here in 1585, the family left in 1588, after his mother had been frightened by the sight of the Spanish Armada sailing up the Channel.1 They kept the property but went to live on the mainland, settling on land they owned in Sussex. Only in 1609, when his father died and John was twenty-four, did he return to the Isle of Wight. This late return to a place John Oglander thought of as home may be at the root of his passionate attachment to Nunwell.

He is more knowable than anyone in these stories, largely because of his extraordinary notebooks, his ‘Bookes of Accoumpts’, the surviving leather-bound volumes written between 1620 and 1648, which have been treasured by the Oglander family ever since.2

At heart they are no more than a steady calculation, quarter by quarter, of what he spent and what he owed, what he lent and what was owed to him, what income he could expect and what, in total, he was worth. But he was too active and too curious to stick merely to figures and over the years the notebooks gradually filled with all the multifarious contents of his mind. The result was a real-time depiction of a man’s life and priorities, a portrait of a member of the seventeenth-century gentry alive in that moment, jumping from one subject to another, from one pre-occupation to the next, from memories to plans, regrets to delights, enemies to friends, events to principles.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.