Полная версия

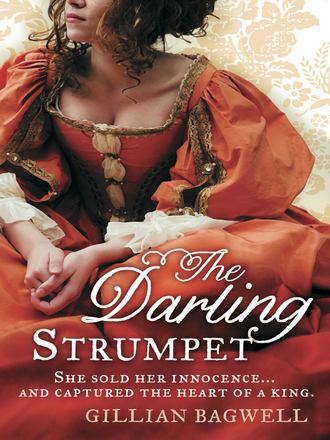

The Darling Strumpet

“Oh.” Nell hardly knew what to say. Of course Rose knew as well as she did that gentlemen like Harry would never marry girls like them, however much they enjoyed their sport and company. But knowing didn’t stop the hurting.

“Hard luck, that is,” she ventured. Rose nodded, turning her head aside and wiping away tears.

“I was a fool to let myself care for him as I did,” Rose said.

“No,” said Nell. “You can’t help how you feel, Rose, any more than you can stop the rain from falling. He don’t deserve you anyway. You’ll soon find someone that treats you far better, I warrant.”

Rose tried to smile, and hugged Nell to her.

“Oh, sweet girl, what would I do without you?”

ONE MORNING IN FEBRUARY, NELL AND ROBBIE WERE AWOKEN EARLY by a pounding at their door. Jane, breathless and red faced, rushed in past Robbie.

“Oh, Nell! Rose has been taken up for theft!” She choked out her story between sobs. “The shoulder clappers came at dawn. They had a gentry cove with them claimed she’d pinched his larum.”

“Oh, no,” Nell gasped. The punishment for the theft of something as valuable as a pocket watch was the gallows.

Nell was so terrified she could not think, but Robbie was cooler.

“Where stands the matter now? What’s been done?”

“Madam’s gone to Whitehall to see can Harry help.”

“And Rose?”

“Clapped up in Newgate.”

Newgate. The name alone evoked darkness and despair. Nell knew that debtors rotted there in misery for years, as her father had languished in prison in Oxford. And all London knew of the regular pageant of death, when condemned prisoners were led from the prison to be driven in carts through jeering crowds and pelted with offal on their way to Tyburn Tree, the enormous three-sided gallows that could accommodate twenty-four nooses, and the resultant twenty-four swinging corpses.

“I must go to her!” Nell cried.

“No,” Robbie said harshly. “You can do her no good.”

But Nell would not be deterred.

“’Tis no place for a girl,” Robbie said, grim faced, shoving his hat onto his head.

“No, and no more is it a place for Rose than it is for me,” Nell retorted, stamping with impatience to be gone. Robbie had no answer to that, and they set off, Nell racing along in front of him.

The winter morning sky was leaden grey, the wind blew bitter cold, and a light shower of snow fell icy wet.

When they arrived at the gates of the prison, Nell’s stomach tightened with fear. The ponderous stone walls towered before her, broken only by narrow slits. The enormous ironclad portals led into a cobbled courtyard, crowded with the morning’s desperate traffic—prisoners in irons shuffling through the doors that led into the depths of the prison; guards and soldiers, grim and armed; the usual London rabble of beggars and urchins; legions of wives, lovers, mothers, sisters, and friends. A foul stench permeated the air, a noxious mixture of human and animal waste, vomit, blood, rotting food, and the unmistakable odour of death. A grizzled guard stopped them.

“If she was shopped this morning, trial might be tomorrow,” the guard shrugged when Robbie explained their errand. “Or mayhap the day after. No way of knowing.”

Robbie turned away, but Nell stayed where she was.

“Can I not see her?” she asked.

“That thou cannot.” The guard ran a tongue over his chapped lips and wiped his nose with the back of a dirty hand. Nell stared at him with hatred, taking in the broken and rotten teeth, the rough stubble on the heavy cheeks, the purple nose running in the cold air. She darted past him through the door. She was young and fast, but his stride and his reach were much longer than hers. He grabbed her by the hair and flung her down. She scrambled to her feet and, in a rage of humiliation and helplessness, ran at the man before Robbie could stop her. Disbelief and growing annoyance on his face, the guard caught her and held her from him at arm’s length. He shook her hard, then lifted her so that her face was close to his. She smelled beer and onions and felt the moist warmth of his breath.

“Get yer arse out of here. And don’t come back, unless you want summat worse.” He dropped her, and she cried out as she landed on the cobblestones. All the fight gone out of her, Nell wanted only to flee before she shamed herself by crying. Robbie, grey faced and silent, helped her to her feet.

“Can you walk?” he asked.

Nell knew he was angry and nodded without meeting his eyes, hot tears falling onto her cheeks.

“We’ll go to Madam Ross’s,” Robbie said shortly. “You can wait until there’s news.”

At Lewkenor’s Lane, Nell was relieved beyond measure that Ned was presiding over the bar and Jack was gone. The girls were gathered in the taproom like a flock of unsettled chickens, some crying, some railing against the cully who had turned Rose in, some taking a morbid enjoyment in the dramatic prospect of the execution of one of their own. They squawked and fluttered at the sight of Nell and Robbie.

“Nell!” Jane cried. “Whatever’s happened to you?”

“Nothing,” said Nell. “We tried to see Rose, is all, and the bandog flung me out on my breech.”

“The brute!” cried Jane.

“Aye, for shame!” chimed black-haired Nan. “What call had he to treat you so?”

“I tried to get past him. Came near to doing it, too,” Nell said, brightening.

“What a plucky thing you are,” said Jane. “Come, let me bind your wounds, little warrior.” The other girls clucked with sympathy while Jane fetched a basin of water and a cloth and gently wiped the grit from the scrapes on Nell’s hands and knees, crying out all over again at the red and purple blotches that already bloomed on her soft skin.

It was after noon when Madam Ross returned.

“Harry’s gone to ask for the king’s help,” she told the girls. “He’ll come here as soon as there’s word.”

So there was nothing to do but wait. Robbie went on to the City. Exhausted by the strain of waiting, Nell went upstairs to Rose’s room and climbed into bed. She could smell Rose’s scent on the bedclothes and pulled them tightly around herself. Wrapped that way, she could close her eyes and believe that Rose lay next to her. Surely Rose was safe and would be back. But fear clutched at her, and she sobbed, finally falling asleep on the tear-dampened pillow.

THE BLEAK AFTERNOON HAD TURNED TO WINTRY DARKNESS WHEN Nell awoke. She raised her head to see Rose coming through the door into the little bedchamber with Harry Killigrew. He was uncharacteristically subdued and stood by awkwardly as Rose flung herself into Nell’s embrace and began to sob.

“Oh, Nelly,” Rose finally whispered, “I was so frightened. I was afeared they was going to turn me off.”

“I tried to get you out,” Nell cried. “But I couldn’t. I’m so sorry.”

“Sorry?” Rose was half laughing and half crying. “Oh, little one. You have the heart of a lion and nought to be sorry for. It took a pardon from the king himself to get me free.”

She nodded towards Harry and, reminded of how much she owed to his help, launched herself into his arms.

“I’ll leave you to your sister,” he said. “I’ll come tomorrow to see how you’re faring.”

When he had gone, Nell tucked Rose into bed and dashed out to the nearest cookhouse for a couple of hot pies. She and Rose sat together in the warm bed, the golden light of the candle in its wall bracket reflected in the black of the icy windowpane. Rose begged Nell to stay the night with her, and they nestled side by side in the darkness.

“When I went there today, it made me think of Da,” Nell whispered.

“Aye. I thought of him, too,” Rose answered. “I cannot bear the thought that he died alone in such a place.”

She drew a shuddering breath.

“When they took me in, I could hear such awful moans and sobbing and screaming. Like souls in hell. And Nell …” She paused.

“They took me down this horrible passage, all dank and grey. And past this little room. And in it I could see arms and legs that had been chopped off, and heads and other parts. Like a butcher shop for men.”

Nell had no words for the horror of the image the words forced into her mind. She thought again of the traitors’ deaths suffered by the men who had killed the first King Charles, and the black and featureless things she had seen on pikes on London Bridge and at the City gates, which she knew were the tarred heads and quarters of executed men. Like souls in hell, Rose had said. But Nell could not imagine a hell that could be any worse than a world in which such things were possible. She slept uneasily that night and dreamed again of the door slamming shut, of being left alone and terrified in a cold and hostile landscape.

It was not until morning that Nell asked Rose the question that had been gnawing at the back of her mind.

“Did you, Rose? Did you pinch the watch?”

“No,” Rose said. “But I think Jack did.”

CHAPTER SEVEN

ROSE CAME SMILING INTO NELL’S LODGING ONE MORNING A FEW weeks after her deliverance from Newgate.

“Harry’s got a way for me to get out of Madam Ross’s!” she said. “When the playhouse opens, there will be need of two wenches to sell oranges and sweetmeats. Harry says he can get me one of the situations, and you can have the other, if you want it.”

“When do we start?”

“Not ’til May,” Rose laughed. “And Orange Moll has to give us the nod.”

“Who’s she?”

“Mary Meggs is her proper name. She holds the licence to sell fruits and nuts and such. But Harry says he’ll make it all come right.”

NELL STOLE A QUICK LOOK AT ROBBIE THAT NIGHT AS HE ATE. “ROBBIE,” she said, “Rose has got me and her work at the playhouse. Selling oranges and so on.”

“You have no need of work.”

“But I could earn my keep. And perhaps I’d meet gentlemen who would want to do business with you.”

Robbie snorted. “Who would want to do business with you, more like.”

Nell held her tongue. First she had to meet Orange Moll. If all went well and the job was hers—well, she’d cross that bridge when she came to it.

A FEW DAYS LATER, SHE AND ROSE PRESENTED THEMSELVES AT WILL’S, the fashionable coffeehouse in Russell Street at Covent Garden, to be inspected by the formidable Orange Moll. Harry was there with her, lounging against the bar. Nell surmised he must have made some impudent remark, for he roared with laughter, while Moll struggled to assume a look of dignified disapproval rather than the chuckle of flattered amusement that threatened to erupt.

Harry hailed the girls, and Moll turned to look at them. She was very round, billowing over the stool on which she sat, her capacious bosom overflowing the low neckline of her dress. Nell noted the shrewd evaluation in the quick glance. She felt like a heifer at Smithfield Market, but could tell that Moll was pleased with what she saw.

“Aye,” Moll said. “They’re comely-looked wenches, both of them. I’ll warrant you’ve been peddling more than oysters, have you not?”

Before Nell could think how to respond, Rose, at an almost imperceptible nod from Harry, looked Orange Moll straight in the eye, and said, “Yes, ma’am. I’m at Madam Ross’s. And Nell was lately, too.”

“Well, that’s all to the good,” said Moll. “A pretty mab who know how to catch a gentleman’s eye, and how to jest and flirt, will sell far more than a prim stick who thinks herself above it. Very well, we’ll give you a try. The plays begin at three. You’ll work from noon until the show is over and the folk have gone. Oranges are sixpence, and a ha’penny of that’s yours to keep.” She gave the girls a knowing smile.

“And there’s more of the ready to be made, for a girl who has her eyes open and her wits about her. Now. Have you ever et an orange? No? Well, here’s your first, then.”

She gave Nell and Rose each an orange and showed them how to peel off the dappled skin to get at the pulp beneath. Nell inhaled the pungent scent and bit into a segment. The sweet tang of the juice was wonderful, different from anything she had tasted.

“Sweet Seville oranges,” said Moll. “All the way from Spain, where it’s warmer.”

The golden oranges, like little suns, conjured in Nell’s mind images of a sultry land of constant languorous summer.

ROBBIE LOOKED GRIM WHEN NELL MENTIONED THE PLAYHOUSE AGAIN that night as they lay in bed. She had been bursting all day with the anxiety of talking to him and the fear of what he would say.

“Let me try it,” she begged. “You’ll see, no ill will come.”

“You may try it for a week,” he said finally. “But I don’t like it a whit. And if you come to any mischance in that time, you’ll stop, and no argument.” He turned his back to her and pulled the covers over his head, and Nell reckoned she had best leave it at that.

THE NIGHT BEFORE SHE WAS TO BEGIN AT THE PLAYHOUSE, NELL’S head was too full of thoughts of the next day for sleep to come. Robbie snored softly next to her in the dark. She slipped out of bed and padded to the window. The moon hung low and bright in the warm night sky. She regarded the stars in wonder. So many of them. She recognised some patterns that she knew—the Great Bear, the Small Bear, the Hen and Chickens—and wondered how many people had looked up at that same moon and stars since time began.

A watchman passed below, crying out, “Two o’clock of a fair, clear night, and all is well.” All was well. Whatever the next day might bring, it must be good. The stars stood guard over her fortunes. And maybe somewhere, too, her father watched.

IN THE MORNING NELL DRESSED IN THE BEST CLOTHES SHE HAD, A skirt and body in russet. She had washed her shift and it peeped out clean and white at her elbows and neckline. She took out her precious ribbon knot of blue and gold from the small box under the bed where she kept her few treasures—the shard of mirror; her little doll; a silk handkerchief left behind in her room at Madam Ross’s by some man; a pink rose she had plucked and hung upside down by a thread to dry, its papery petals giving off a sweet scent, like memories of another day.

Rose arrived, flushed and smiling, her brown curls and blue eyes set off by a saffron-coloured gown. As soon as she knew she had work at the playhouse, she had left Madam Ross’s and moved into a room above the nearby Cat and Fiddle Tavern, and she looked happier than Nell remembered seeing her.

It wasn’t far to the playhouse, but as Rose and Nell stepped into Bridges Street, the familiar thoroughfare seemed altogether different. A parade of fine carriages choked the way, and Nell realised with a start that their destination must be the theatre. She had not thought about so many people going to hear the play. But it stood to reason that everyone would want to be present for the first performance at the fine new Theatre Royal. And she would be a part of it! She felt a thrill, and then a stab of doubt. What made her so sure of herself? Maybe Moll would decide that she had made a mistake, that she wanted someone older, taller, fairer. Someone better. After all, who was she but a ragamuffin from the squalid streets?

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.