Полная версия

The Complete Tamuli Trilogy: Domes of Fire, The Shining Ones, The Hidden City

‘Be nice, Sarathi,’ she murmured.

‘Then no one is really in charge here in Eosia? No one has the absolute authority to make final decisions?’

‘It’s a responsibility we share, your Excellency,’ Ehlana explained. ‘We enjoy sharing things, don’t we Sarathi?’

‘Of course.’ Dolmant said it without much enthusiasm.

‘The rough-and-tumble, give-and-take nature of Eosian politics have a certain utility, your Excellency,’ Stragen drawled. ‘Consensus politics gives us the advantage of bringing together a wide range of views.’

‘In Tamuli, we feel that having only one view is far less confusing.’

‘The Emperor’s view? What happens when the emperor happens to be an idiot? Or a madman?’

‘The government usually works around him,’ Oscagne admitted blandly. ‘Such imperial misfortunes seldom live very long for some reason, however.’

‘Ah,’ Stragen said.

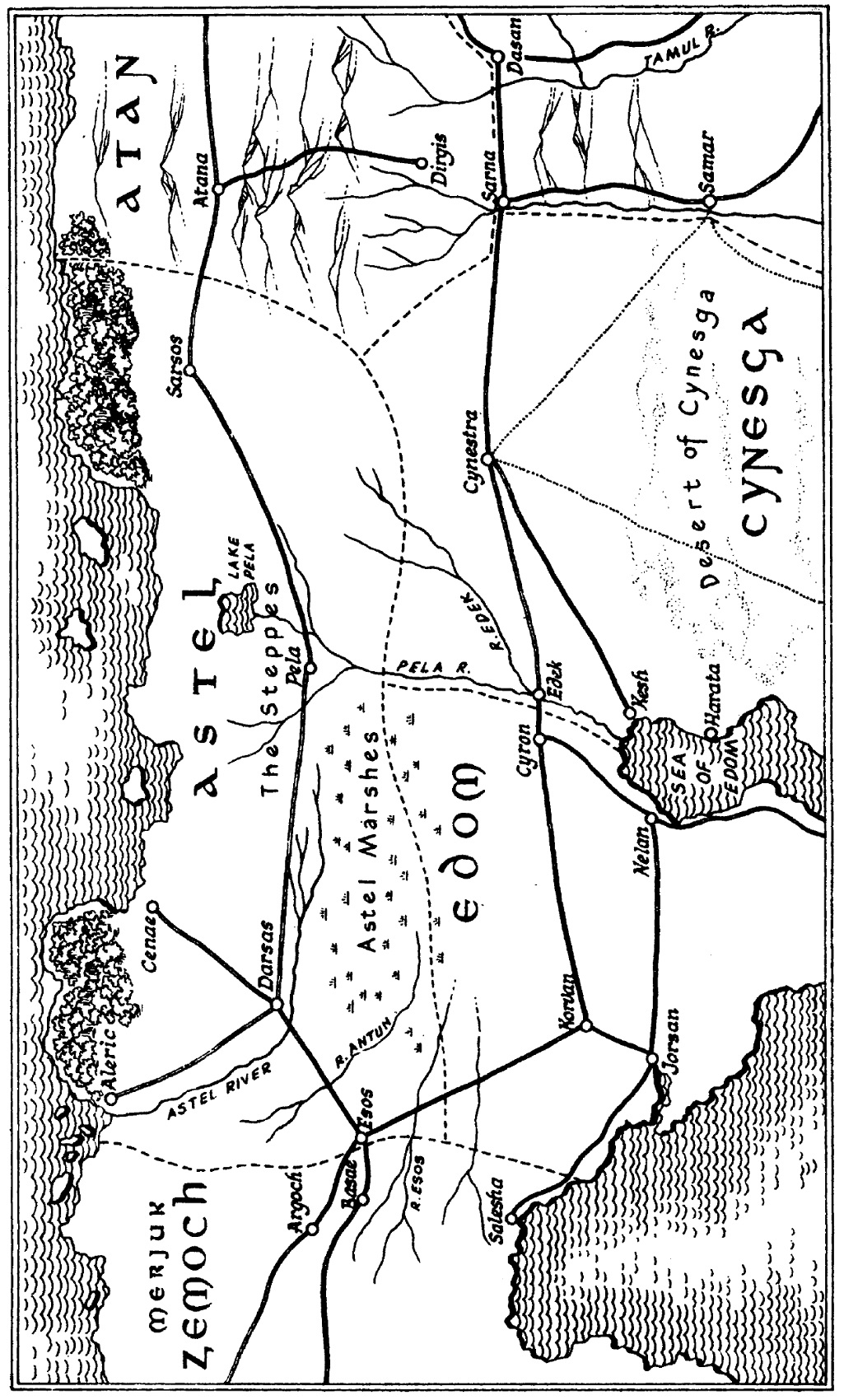

‘Perhaps we should get down to work,’ Emban said. He crossed the room to a large map of the known world hanging on the wall. ‘The fastest way to travel is by sea,’ he noted. ‘We could sail from Madel in Cammoria out through the Inner Sea and then around the southern tip of Daresia and then up the east coast to Matherion.’

‘We?’ Sir Tynian asked.

‘Oh, didn’t I tell you?’ Emban said. I’ll be going along. Ostensibly, I’ll be Queen Ehlana’s spiritual advisor. In actuality, I’ll be the Archprelate’s personal envoy.’

‘It’s probably wiser to keep the Elenian flavour of the expedition,’ Dolmant explained, ‘for public consumption, anyway. Let’s not complicate things by sending two separate missions to Matherion simultaneously.’

Sparhawk had to move quickly, and he didn’t have much to work with. ‘Travelling by ship has certain advantages,’ he conceded, ‘but I think there’s a major drawback.’

‘Oh?’ Emban said.

‘It satisfies the requirements of a state visit, right enough, but it doesn’t do very much to address our real reason for going to Tamuli. Your Excellency, what’s likely to happen when we reach Matherion?’

‘The usual,’ Oscagne shrugged. ‘Audiences, banquets, reviewing troops, concerts, that giddy round of meaningless activity we all adore.’

‘Precisely,’ Sparhawk agreed. ‘And we won’t really get anything done, will we?’

‘Probably not.’

‘But we aren’t going to Tamuli for a month-long carouse. What we’re really going there for is to find out what’s behind all the upheaval. We need information, not entertainment, and the information’s probably out in the hinterlands, not in the capital. I think we should find some reason to go across country.’ It was a practical suggestion, and it rather neatly concealed Sparhawk’s real reason for wanting to go overland.

Emban’s expression was pained. ‘We’d be on the road for months that way.’

‘We can get as much done as we’ll accomplish in Matherion by staying home, your Grace. We have to get outside the Capital.’

Emban groaned. ‘You’re absolutely bent on making me ride a horse all the way from here to Matherion, aren’t you, Sparhawk?’

‘You could stay home, your Grace,’ Sparhawk suggested. ‘We could always take Patriarch Bergsten instead. He’d be better in a fight anyway.’

‘That will do, Sparhawk,’ Dolmant said firmly.

‘Consensus politics are very interesting, Milord Stragen,’ Oscagne observed. ‘In Matherion, we’d have followed the course suggested by the Primate of Ucera without any further discussion. We try to avoid raising the possibility of alternatives whenever possible.’

‘Welcome to Eosia, your Excellency,’ Stragen smiled.

‘Permission to speak?’ Khalad said politely.

‘Of course,’ Dolmant replied.

Khalad rose, went to the map and began measuring distance. ‘A good horse can cover ten leagues a day, and a good ship can cover thirty – if the wind holds.’ He frowned and looked around. ‘Why is Talen never around when you need him?’ he muttered. ‘He can compute these numbers in his head. I have to count them up on my fingers.’

‘He said he had something to take care of,’ Berit told him.

Khalad grunted. ‘All we’re really interested in is what’s going on in Daresia, so there’s no need to ride across Eosia. We could sail from Madel the way Patriarch Emban suggested, go out through the Inner Sea and then up the east coast of Zemoch to –’ He looked at the map and then pointed. ‘To Salesha here. That’s nine hundred leagues – thirty days. If we were to follow the roads, it’d probably be the same distance overland, but that would take us ninety days. We’d save two months at least.’

‘Well,’ Emban conceded grudgingly, ‘that’s something, anyway.’

Sparhawk was fairly sure that they could save much more than sixty days. He looked across the room at his daughter, who was playing with her kitten under Mirtai’s watchful eye. Princess Danae was quite frequently present at conferences where she had no real business. People did not question her presence for some reason. Sparhawk knew that the Child Goddess Aphrael could tamper with the passage of time, but he was not entirely certain that she could manage it so undetectably in her present incarnation as she had when she had been Flute.

Princess Danae looked back at him and rolled her eyes upward with a resigned expression that spoke volumes about his limited understanding, and then she gravely nodded her head.

Sparhawk breathed somewhat easier after that. ‘Now we come to the question of the queen’s security,’ he continued. ‘Ambassador Oscagne, how large a retinue could my wife take with her without raising eyebrows?’

‘The conventions are a little vague on that score, Sir Sparhawk.’

Sparhawk looked around at his friends. ‘If I thought I could get away with it, I’d take the whole body of the militant orders with me,’ he said.

‘We’ve defined our trip as a visit, Sparhawk,’ Tynian said, ‘not an invasion. Would a hundred armoured knights alarm his Imperial Majesty, your Excellency?’

‘It’s a symbolic sort of number,’ Oscagne agreed after a moment’s consideration, ‘large enough for show, but not so large as to appear threatening. We’ll be going through Astel, and you can pick up an escort of Atans in the capitol at Darsas. A sizeable escort for a state visitor shouldn’t raise too many eyebrows.’

‘Twenty-five knights from each order, wouldn’t you think, Sparhawk?’ Bevier suggested. ‘The differences in our equipment and the colours of our surcoats would make the knights appear more ceremonial than utilitarian. A hundred Pandions by themselves might cause concern in some quarters.’

‘Good idea,’ Sparhawk agreed.

‘You can bring more if you want, Sparhawk,’ Mirtai told him. ‘There are Peloi on the steppes of Central Astel. They’re the descendants of Kring’s ancestors. He might just want to visit his cousins in Daresia.’

‘Ah yes,’ Oscagne said, ‘the Peloi. I’d forgotten that you had those wild-men here in Eosia too. They’re an excitable and sometimes unreliable people. Are you certain that this Kring person would be willing to accompany us?’

‘Kring would ride into fire if I asked him to,’ Mirtai replied confidently.

‘The Domi is much taken with our Mirtai, your Excellency,’ Ehlana smiled. ‘He comes to Cimmura three or four times a year to propose marriage to her.’

‘The Peloi are warriors, Atana,’ Oscagne noted. ‘You would not demean yourself in the eyes of your people were you to accept him.’

‘Husbands take their wives more or less for granted, Oscagne,’ Mirtai pointed out with a mysterious little smile. ‘A suitor, on the other hand, is much more attentive, and I rather enjoy Kring’s attentions. He writes very nice poetry. He compared me to a golden sunrise once. I thought that was rather nice.’

‘You never wrote any poetry for me, Sparhawk,’ Ehlana accused her husband.

‘The Elene language is limited, my Queen,’ he responded. ‘It has no words which could do you justice.’

‘Nice try,’ Kalten murmured.

‘I think we all might want to spend a bit of time on some correspondence at this point,’ Dolmant told them. ‘There are all sorts of arrangements to be made. I’ll put a fast ship at your disposal, Ambassador Oscagne. You’ll want to advise your emperor that the Queen of Elenia’s coming to call.’

‘With the Archprelate’s permission, I’ll communicate with my government by dispatch rather than in person. There are social and political peculiarities in various parts of the empire. I could be very helpful in smoothing her Majesty’s path if I went with her.’

‘I’ll be very pleased to have a civilised man along, your Excellency,’ Ehlana smiled. ‘You have no idea what it’s like being surrounded by men whose clothes have all been tailored by blacksmiths.’

Talen entered the chamber with an excited expression on his face.

‘Where have you been?’ The question came from several parts of the room.

‘It’s such a comfort to be so universally loved that my activities arouse this breathless curiosity,’ the boy said with an exaggerated and sardonic bow. ‘I’m quite overwhelmed by this demonstration of affection.’

Ambassador Oscagne looked quizzically at Dolmant.

‘It would take far too long to explain, your Excellency,’ Dolmant said wearily. ‘Just keep a close watch on your valuables when that boy’s in the room.’

‘Sarathi,’ Talen protested. ‘I haven’t stolen a single thing for almost a week now.’

‘That’s a start, I suppose,’ Emban noted.

‘Old habits die hard, your Grace,’ Talen smirked. ‘Anyway, since you’re all dying to know, I was out in the city sort of nosing around, and I ran across an old friend. Would you believe that Krager’s here in Chyrellos?’

Chapter 7

Komier,

My wife’s making a state visit to Matherion in Tamuli. We’ve discovered that the present turmoil in Lamorkand is probably originating in Daresia, so we’re using Ehlana’s trip to give us the chance to go there to see what we can find out. I’ll keep you advised. I’m borrowing twenty-five Genidian Knights from your local chapterhouse to serve as a part of the honour guard.

I’d suggest that you do what you can to keep Avin Wargunsson from cementing any permanent alliances with Count Gerrich in Lamorkand. Gerrich is rather deeply involved in some kind of grand plan that goes far beyond the borders of Lamorkand itself. Dolmant probably wouldn’t be too displeased if you, Darrellon and Abriel can contrive some excuse to go to Lamorkand and step on the fellow’s neck. Watch out for magic, though. Gerrich’s getting help from somebody who knows more than he’s supposed to. Ulath’s sending you more details.

– Sparhawk.

‘Isn’t that just a little blunt, dear?’ Ehlana said, reading over her husband’s shoulder. She smelled very good.

‘Komier’s a blunt sort of fellow, Ehlana,’ Sparhawk shrugged, laying down his quill, ‘and I’m not really very good at writing letters.’

‘I noticed.’ They were in their ornate apartments in one of the Church buildings adjoining the Basilica where they had spent the day composing messages to people scattered over most of the continent.

‘Don’t you have letters of your own to write?’ Sparhawk asked his wife.

‘I’m all finished. All I really had to do was send a short note to Lenda. He knows what to do.’ She glanced across the room at Mirtai, who sat patiently snipping the tips off Mmrr’s claws. Mmrr was not taking it very well. Ehlana smiled. ‘Mirtai’s communication with Kring was much more direct. She called in an itinerant Peloi and told him to ride to Kring with her command to ride to Basne on the Zemoch-Astel border with a hundred of his tribesmen. She said that if he isn’t waiting when she gets there, she’ll take it to mean that he doesn’t love her.’ Ehlana pushed her pale blonde hair back from her brow.

‘Poor Kring,’ Sparhawk smiled. ‘She could raise him from the dead with a message like that. Do you think she’ll ever really marry him?’

‘That’s very hard to say, Sparhawk. He does have her attention, though.’

There was a knock at the door, and Mirtai rose to let Kalten in. ‘It’s a beautiful day out there,’ the blond man told them. ‘We’ll have good weather for the trip.’

‘How are things coming along?’ Sparhawk asked him.

‘We’re just about all ready.’ Kalten was wearing a green brocade doublet, and he bowed extravagantly to the queen. ‘Actually, we are ready. About the only things happening now are the usual redundancies.’

‘Could you clarify that just a bit, Sir Kalten?’ Ehlana said.

He shrugged. ‘Everyone’s going over all the things everyone else has done to make sure that nothing’s been left out.’ He sprawled in a chair. ‘We’re surrounded by busybodies, Sparhawk. Nobody seems to be able to believe that anybody else can do something right. If Emban asks me if the knights are all ready to ride about one more time, I think I’ll strangle him. He has no idea at all about what’s involved in moving a large group of people from one place to another. Would you believe that he was going to try to put all of us on one ship? Horses and all?’

‘That might have been just a bit crowded,’ Ehlana smiled. ‘How many ships did he finally decide on?’

‘I’m not sure. I still don’t know for certain how many people are going. Your attendants are all absolutely convinced that you’ll simply die without their company, my Queen. There are about forty or so who are making preparations for the trip.’

‘You’d better weed them out, Ehlana,’ Sparhawk suggested. ‘I don’t want to be saddled with the entire court.’

‘I will need a few people, Sparhawk – if only for the sake of appearances.’

Talen came into the room. The gangly boy was wearing what he called his ‘street clothes’ – slightly mismatched, very ordinary and just this side of shabby. ‘He’s still out there,’ he said, his eyes bright.

‘Who?’ Kalten asked.

‘Krager. He’s creeping around Chyrellos like a lost puppy looking for a home. Stragen’s got people from the local thieves’ community watching him. We haven’t been able to figure out exactly what he’s up to just yet. If Martel were still alive, I’d almost say he’s doing the same sort of thing he used to do – letting himself be seen.’

‘How does he look?’

‘Worse.’ Talen’s voice cracked slightly. It was still hovering somewhere between soprano and baritone. ‘The years aren’t treating Krager very well. His eyes look like they’ve been poached in bacon grease. He looks absolutely miserable.’

‘I think I can bear Krager’s misery,’ Sparhawk noted. ‘He’s beginning to make me just a little tired, though. He’s been sort of hovering around the edge of my awareness for the last ten years or more – sort of like a hangnail or an ingrown toenail. He always seems to be working for the other side, but he’s too insignificant to really worry about.’

‘Stragen could ask one of the local thieves to cut his throat,’ Talen offered.

Sparhawk considered it. ‘Maybe not,’ he decided. ‘Krager’s always been a good source of information. Tell Stragen that if the opportunity happens to come up, we might want to have a little chat with our old friend, though. The offer to braid his legs together usually makes Krager very talkative.’

Ulath stopped by about a half hour later. ‘Did you finish that letter to Komier?’ he asked Sparhawk.

‘He has a draft copy, Sir Ulath,’ Ehlana replied for her husband. ‘It definitely needs some polish.’

‘You don’t have to polish things for Komier, your Majesty. He’s used to strange letters. One of my Genidian brothers sent him a report written on human skin once.’

She stared at him. ‘He did what?’

‘There wasn’t anything else handy to write on. A Genidian Knight just arrived with a message for me from Komier, though. The knight’s going back to Emsat, and he can carry Sparhawk’s letter if it’s ready to go.’

‘It’s close enough,’ Sparhawk said, folding the parchment and dribbling candle wax on it to seal it. ‘What did Komier have to say?’

‘It was good news for a change. All the Trolls have left Thalesia for some reason.’

‘Where did they go?’

‘Who knows? Who cares?’

‘The people who live in the country they’ve gone to might be slightly interested,’ Kalten suggested.

‘That’s their problem,’ Ulath shrugged. ‘It’s funny, though. The Trolls don’t really get along with each other. I couldn’t even begin to guess at a reason why they’d all decide to pack up and leave at the same time. The discussions must have been very interesting. They usually kill each other on sight.’

‘There’s not much help I can give you, Sparhawk,’ Dol-mant said gravely when the two of them met privately later that day. ‘The Church is fragmented in Daresia. They don’t accept the authority of Chyrellos, so I can’t order them to assist you.’ Dolmant’s face was careworn, and his white cassock made his complexion look sallow. In a very real sense, Dolmant ruled an empire that stretched from Thalesia to Cammoria, and the burdens of his office bore down on him heavily. The change they had all noticed in their friend in the past several years derived more likely from that than from any kind of inflated notion of his exalted station.

‘You’ll get more co-operation in Astel than either Edom or Daconia,’ he continued. ‘The doctrine of the Church of Astel is very close to ours – close enough that we even recognise Astellian ecclesiastical rank. Edom and Daconia broke away from the Astellian Church thousands of years ago and went their own way.’ ‘The Archprelate smiled ruefully. The sermons in those two kingdoms are generally little more than hysterical denunciations of the Church of Chyrellos – and of me personally. They’re anti-hierarchical, much like the Rendors. If you should happen to go into those two kingdoms, you can expect the Church there to oppose you. The fact that you’re a Church Knight will be held against you rather than the reverse. The children there are all taught that the Knights of the Church have horns and tails. They’ll expect you to burn churches, murder clergymen and enslave the people.’

‘I’ll do what I can to stay away from those places, Sarathi,’ Sparhawk assured him. ‘Who’s in charge in Astel?’

‘The Archimandrite of Darsas is nominally the head of the Astellian Church. It’s an obscure rank approximately the equivalent of our “patriarch”. The Church of Astel’s organised along monastic lines. They don’t have a secular clergy there.’

‘Are there any other significant differences I should know about?’

‘Some of the customs are different – liturgical variations primarily. I doubt that you’ll be asked to conduct any services, so that shouldn’t cause any problems. It’s probably just as well. I heard you deliver a sermon once.’

Sparhawk smiled. ‘We serve in different ways, Sarathi. Our Holy Mother didn’t hire me to preach to people. How do I address the Archimandrite of Darsas – in case I meet him?’

‘Call him “your Grace”, the same as you would a patriarch. He’s an imposing man with a huge beard, and there’s nothing in Astel that he doesn’t know about. His priests are everywhere. The people trust them implicitly, and they all submit weekly reports to the Archimandrite. The Church has enormous power there.’

‘What a novel idea.’

‘Don’t mistreat me, Sparhawk. Things haven’t been going very well for me lately.’

‘Would you be willing to listen to an assessment, Dolmant?’

‘Of me personally? Probably not.’

‘I wasn’t talking about that. You’re too old to change, I expect. I’m talking about your policies in Rendor. Your basic idea was good enough, but you went at it the wrong way.’

‘Be careful, Sparhawk. I’ve sent men to monasteries permanently for less than that.’

‘Your policy of reconciliation with the Rendors was very sound. I spent ten years down there, and I know how they think. The ordinary people in Rendor would really like to be reconciled with the Church – if for no other reason than to get rid of all the howling fanatics out in the desert. Your policy is good, but you sent the wrong people there to carry it out.’

‘The priests I sent are all experts in doctrine, Sparhawk.’

‘That’s the problem. You sent doctrinaire fanatics down there. All they want to do is punish the Rendors for their heresy.’

‘Heresy is a sort of problem, Sparhawk.’

‘The heresy of the Rendors isn’t theological, Dolmant. They worship the same God we do, and their body of religious belief is identical to ours. The disagreements between us are entirely in the field of Church government. The Church was corrupt when the Rendors broke away from us. The members of the Hierocracy were sending relatives to fill Church positions in Rendor, and those relatives were parasitic opportunists who were far more interested in lining their own purses than caring for the souls of the people. When you get right down to it, that’s why the Rendors started murdering primates and priests – and they’re doing it for exactly the same reason now. You’ll never reconcile the Rendors to the Church if you try to punish them. They don’t care who’s governing our Holy Mother. They’ll never see you personally, my friend, but they will see their local priest – probably every day. If he spends all his time calling them heretics and tearing the veils off their women, they’ll kill him. It’s as simple as that.’

Dolmant’s face was troubled. ‘Perhaps I have blundered,’ he admitted. ‘Of course if you tell anybody I said that, I’ll deny it.’

‘Naturally.’

‘All right, what should I do about it?’

Sparhawk remembered something then. ‘There’s a Vicar in a poor church in Borrata,’ he said. ‘He’s probably the closest thing to a saint I’ve ever seen, and I didn’t even get his name. Berit knows what it is though. Disguise some investigators as beggars and send them down to Cammoria to observe him. He’s exactly the kind of man you need.’

‘Why not just send for him?’

‘He’d be too tongue-tied to speak to you, Sarathi. He’s what they had in mind when they coined the word “humble”. Besides, he’d never leave his flock. If you order him to Chyrellos and then send him to Rendor, he’ll probably die within six months. He’s that kind of man.’

Dolmant’s eyes suddenly filled with tears. ‘You trouble me, Sparhawk,’ he said. ‘You trouble me. That’s the ideal we all had when we took holy orders.’ He sighed. ‘How did we all get so far away from it?’

‘You got too much involved in the world, Dolmant,’ Sparhawk told him gently. ‘The Church has to live in the world, but the world corrupts her much faster than she can redeem it.’

‘What’s the answer to that problem, Sparhawk?’

‘I honestly don’t know, Sarathi. Maybe there isn’t any.’

‘Sparhawk.’ It was his daughter’s voice, and it was somehow inside his head. He was passing through the nave of the Basilica, and he quickly knelt as if in prayer to cover what he was really doing.

‘What is it, Aphrael?’ he asked silently.

‘You don’t have to genuflect to me, Sparhawk.’ Her voice was amused.

‘I’m not. If they catch me walking through the corridors holding long conversations with somebody who isn’t there, they’ll lock me up in an asylum.’

‘You look very reverential in that position, though. I’m touched.’

‘Was there something significant, or are you just amusing yourself?’

‘Sephrenia wants to talk with you again.’

‘All right. I’m in the nave right now. Come down and meet me here. We’ll go up to the cupola again.’

‘I’ll meet you up there.’

‘There’s only one stairway leading up there, Aphrael. We have to climb it.’

‘You might have to, but I don’t. I don’t like going into the nave, Sparhawk. I always have to stop and talk with your God, and He’s so tedious most of the time.’

Sparhawk’s mind shuddered back from the implications of that.

The dried-out wooden stairs circling up to the top of the dome still shrieked their protest as Sparhawk mounted. It was a long climb, and he was winded when he reached the top.