Полная версия

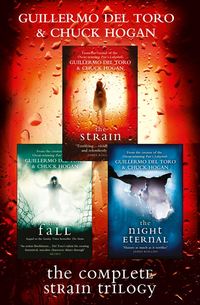

The Complete Strain Trilogy: The Strain, The Fall, The Night Eternal

He still didn’t feel right about that van. Gus turned over his hat underneath the table and checked the inside band again. The original five $10 bills he had gotten from that dude, plus the $500 he had earned for driving the van into the city, were still tucked in there. Tempting him. He and Felix could have a hell of a lot of fun on half that amount. Take home half for his madre, money she needed, money she could use.

Problem was, Gus knew himself. Problem was stopping at half. Problem was walking around with unspent money on his person.

He should get Felix to run him home right now. Unburden himself of half this haul. Slip it to his madre without his dirtbag brother Crispin knowing. Crackhead could sniff out dollars like a fiend.

Then again, this was dirty money. He had done something wrong to get it—clearly, though he didn’t know what he’d done—and handing the money over to his madre was like passing on a curse. Best thing to do with dirty money is spend it quick, get rid of it—easy come, easy go.

Gus was torn. He knew that, once he started drinking, he lost all impulse control. And Felix was the gasoline to his flame. The two of them would burn through $550 before sunup, and then, instead of bringing something beautiful home to his madre, instead of bringing home something good, he would come in dragging his own hungover ass, hat all dented to hell, empty pockets turned inside out.

“Penny for your thoughts, Gusto,” said Felix.

Gus shook his head. “I’m my own worst enemy, ’mano. I’m like a fucking mutt sniffing in the street who don’t know what tomorrow means. I got a dark side, amigo, and sometimes it takes me over.”

Felix sipped his giant-ass Coke. “So what are we doing in this greasy spoon? Let’s get out and meet some young ladies tonight.”

Gus ran his thumb along the leather rim inside his hat, over the folded cash Felix knew nothing about—so far. Maybe just a hundred. Two hundred, half for each. Pull out exactly that much, that was his limit, no more. “Gotta pay to play, right, ’mano?”

“Fuck yeah.”

Gus looked away and saw a family next to him, dressed for the theater, rising and leaving with their desserts unfinished. Because of Felix’s language, Gus guessed. By the looks of these Midwestern kids, they had never heard hard talk. Well, fuck them. You come into this town, you keep your kids out past nine o’clock, you risk them seeing the full show.

Felix finally finished his slop and Gus eased his cash-filled hat onto his head and they sauntered out into the night. They were walking on Forty-fourth Street, Felix sucking on a cigarette, when they heard screams. It didn’t quicken their pace any, hearing screams in Midtown Manhattan. Not until they saw the fat, naked guy shuffling across the street at Seventh and Broadway.

Felix nearly spit out his cigarette laughing. “Gusto, you see that shit?” He started to jog ahead, like a bystander called by a barker to a show.

Gus wasn’t into it. He followed slowly after him.

People in Times Square were making way for this guy and his pasty, floppy ass. Women screamed at the sight, half laughing, covering their eyes or their mouths or both. A young bachelorette party group snapped photos with their phones. Every time the guy turned, a new group got a look at his shriveled, flesh-buried junk, and howled.

Gus wondered where the cops were. This was America for you: a brown brother couldn’t even duck into a doorway for a discreet piss without getting hassled, yet a white guy can parade naked through the crossroads of the world and get a free pass.

“Wasted off his ass,” hooted Felix, following the fool, along with a loose bunch of others, many drunk themselves, savoring the street theater. The lights of the brightest intersection in the world—Times Square is a slashing X of avenues, walled with eye-popping advertisements and word crawls, a pinball game run through with never-ending traffic—dazzled the fat man, set him spinning. He lunged about, lurching like a circus bear on the loose.

Felix’s crowd of carousers laughed and reared back when the man turned and staggered toward them. He was getting bolder now, or a little panicked, like a frightened animal, and more confused and seemingly—sometimes he pressed a hand to his throat, as though choking—more pained. Everything was really lively until the pale, fat man lashed out at a laughing woman, grabbing her by the back of her head. The woman screamed and twisted and a part of her head came off in his hand—for a moment it looked as though he had ripped open her skull—but it was just her frizzy black extensions.

The attack crossed the line from fun into fright. The fat man stumbled out into traffic with the fistful of fake hair still in his hand, and the crowd followed, pursuing him now, growing angry, yelling. Felix took the lead, crossing to the traffic island after this guy. Gus went along, but away from the crowd, threading through the honking cars. He was calling to Felix to come away, to be done with this. This was not going to end well.

The fat man was advancing toward a family gathered in the island to take in Times Square at night. He had them backed up against the traffic shooting past, and when the father tried to intervene he got knocked back hard. Gus recognized them as the theatergoing family from the restaurant. The mother seemed more concerned about shielding her kids’ eyes from the sight of the naked man than protecting herself. She got grabbed by the back of the neck, pulled close up against his sagging belly and pendulous man breasts. The crazy man’s mouth opened as though he wanted a kiss. But then it kept opening, like a snake’s mouth—clearly dislocating the jaw with a soft pop.

Gus had no love for tourists, but he didn’t even think before coming up behind the guy and hook-arming him in a headlock. He choked back on him strong, the guy’s neck surprisingly muscular beneath the loose folds of flesh. Gus had the advantage, though, and the guy released the mother, falling against her husband in front of her screaming kids.

Now Gus was stuck. He had the naked man locked up, the big bear’s arms pinwheeling. Felix came up in front to help … but then stopped. He was staring at the naked guy’s face as if there was something really wrong there. A few people behind him reacted the same, others turned away in horror, but Gus couldn’t see why. He did feel the guy’s neck undulate under his forearm, very unnaturally—almost as though he were swallowing sideways. Felix’s look of disgust made him think the fat guy was maybe suffocating under his choke hold, so Gus relaxed his grip a bit—

—just enough for the guy, with the animal strength of the insane, to hurl Gus off with a hairy elbow.

Gus fell to the sidewalk hard and his hat popped off. He turned in time to see it roll off the curb and into traffic. Gus jumped up and started after his hat and his money—but Felix’s yell spun him back. The guy had Felix wrapped up in some kind of maniacal embrace, the big man’s mouth going at Felix’s neck. Gus saw Felix’s hand pull something from his back pocket, flicking it open with a wrist flip.

Gus ran toward Felix before Felix could use the knife, dropping a shoulder into the fat man’s side, feeling ribs crack, sending the tub of flesh sprawling. Felix fell too, Gus seeing blood spilling down the front of Felix’s neck, and—more shockingly—a look of outright terror on his compadre’s face. Felix sat up, dropping the knife in order to grip his neck, and Gus had never seen Felix look that way. Gus knew then that something bizarre had happened—was happening—he just didn’t know what. All he knew was that he had to act in order to make his friend right again.

Gus reached for the knife, taking its burled black grip in his hand as the naked man got to his feet. The guy stood with his hand covering his mouth, almost as though trying to contain something in there. Something squirming. Blood rimmed his fat cheeks and stained his chin—Felix’s blood—as he started toward Gus with his free hand outstretched.

He came fast—faster than a man of his size should have—shoving Gus down backward, before he could react. Gus’s bare head smacked against the sidewalk—and for a moment everything was silent. He saw the Times Square billboards flashing above him in a kind of liquid slow motion … a young model staring down at him, wearing only a bra and panties … then the big man. Looming over him. Something undulating inside his mouth as he stared at Gus with empty, dark eyes …

The man dropped to one knee, choking out this thing in his throat. Pinkish and hungry, it shot out at Gus with the greedy speed of a frog’s darting tongue. Gus slashed at the thing with his knife, cutting and stabbing like a dreamer fighting some creature in a nightmare. He didn’t know what it was—only that he wanted it away from him, wanted to kill it. The fat man reeled back, making a noise like squealing. Gus kept up his slashing, cutting the man’s neck, slicing his throat to ribbons.

Gus kicked away and the guy got to his feet, hands over his mouth and throat. He was bleeding white—not red—a creamy substance thicker and brighter than milk. He stumbled backward off the curb and fell into the moving traffic.

The truck tried to stop in time. That was the worst of it. After rolling over his face with the front tires, the rear set stopped right on the fat man’s crushed skull.

Gus staggered to his feet. Still dizzy from his fall, he looked down at the blade of Felix’s knife in his hand. It was stained white.

He was hit from behind then, his arms wrapped up, his shoulder driven into the pavement. He reacted as though it were the fat man still attacking him, writhing and kicking.

“Drop the knife! Drop it!”

He got his head around and saw three red-faced cops on him, two more behind him aiming guns.

Gus released the knife. He allowed his arms to be wrenched behind him, where they were cuffed. His adrenaline exploded. He said, “Fucking now you’re here?”

“Stop resisting!” said the cop, cracking Gus’s face into the pavement.

“He was attacking this family here—ask them!”

Gus turned.

The tourists were gone.

Most of the crowd was gone. Only Felix remained, seated on the edge of the island in a daze, gripping his throat—as a blue-gloved cop shoved him down, dropping a knee into his side.

Beyond Felix, Gus saw a small black thing rolling farther out into traffic. His hat, with all his dirty money still inside the brim—a slow-rolling taxi crushing it flat, Gus thinking, This was America for you.

Gary Gilbarton poured himself a whisky. The family—the extended family, both sides—and friends were all gone finally, leaving behind stacks of take-out food cartons in the refrigerator and wastebaskets full of tissues. Tomorrow they’d be back to their lives, and with a story to tell.

My twelve-year-old niece was on that plane …

My twelve-year-old cousin was on that plane …

My neighbor’s twelve-year-old daughter was on that plane …

Gary felt like a ghost walking through his nine-room home in the leafy suburb of Freeburg. He touched things—a chair, a wall—and felt nothing. Nothing mattered anymore. Memories could console him, but were more likely to drive him mad.

He had disconnected all the telephones after reporters started calling, wanting to know about the youngest casualty on board. To humanize the story. Who was she? they asked him. It would take Gary the rest of his life to work on a paragraph about his daughter, Emma. It would be the longest paragraph in history.

He was more focused on Emma than he was Berwyn, his wife, because children are our second selves. He loved Berwyn, and she was gone. But his mind kept circling around his lost little girl like water circling an ever-emptying drain.

That afternoon, a lawyer friend—a guy Gary hadn’t had over to the house in maybe a year—pulled him aside in the study. He sat Gary down and told him that he was going to be a very rich man. A young victim like Em, with a much longer timeline of life lost, guaranteed a huge settlement payout.

Gary did not respond. He did not see dollar signs. He did not throw the guy out. He truly did not care. He felt nothing.

He had spurned all the offers from family and friends to spend the night so that he would not be alone. Gary had convinced one and all that he was fine, though thoughts of suicide had already occurred to him. Not just thoughts: a silent determination; a certainty. But later. Not now. Its inevitability was like a balm. The only sort of “settlement” that would mean anything to him. The only way he was getting through all this now was knowing that there would be an end. After all the formalities. After the memorial playground was erected in Emma’s honor. After the scholarship was funded. But before he sold this now-haunted house.

He was standing in the middle of the living room when the doorbell rang. It was well after midnight. If it was a reporter, Gary would attack and kill him. It was as simple as that. To violate this time and place? He would tear the interloper apart.

He whipped open the door … and then all at once the pent-up mania went out of him.

A girl stood barefoot on the welcome mat. His Emma.

Gary Gilbarton’s face crumpled in disbelief, and he slipped to his knees in front of her. Her face showed no reaction, no emotion. Gary reached out to his daughter—then hesitated. Would she pop like a soap bubble and disappear again forever?

He touched her arm, gripping her thin biceps. The fabric of her dress. She was real. She was there. He grasped her and pulled her to him, hugging her, wrapping her up in his arms.

He pulled back and looked at her again, pushing the stringy hair off her freckled face. How could this be? He looked around outside, scanning his misty front yard to see who had brought her.

No car in the driveway, no sound of an automobile engine pulling away.

Was she alone? Where was her mother?

“Emma,” he said.

Gary got to his feet and led her inside, closing the front door, switching on the light. Em looked dazed. She wore the dress her mother had bought her for the trip, that made her look so grown up as she twirled around when she’d first tried it on for him. There was dirt on one sleeve—and perhaps blood. Gary spun her around, looking her over and finding more blood on her bare feet—no shoes?—and dirt all over, and scrapes on her palms and bruises on her neck.

“What happened, Em?” he asked her, holding her face in his palms. “How did you …?”

The wave of relief struck him again, nearly knocking him over, and he grasped her tight. He picked her up and carried her over to the sofa, sitting her there. She was traumatized, and oddly passive. So unlike his smiling, headstrong Emma.

He felt her face, the way her mother always did when Emma acted strangely, and it was hot. So hot that her skin felt sticky, and she was terribly pale, nearly translucent. He saw veins beneath the surface, prominent red veins he had never seen before.

The blue in her eyes seemed to have faded. A head wound, probably. She was in shock.

Thoughts of hospitals ran through his head, but he wasn’t letting her out of this house now, never again.

“You’re home now, Em,” he said. “You’re going to be fine.”

He took her hand and tugged on it to get her to stand, leading her into the kitchen. Food. He installed her in her chair at the table, watching her from the counter as he toasted two chocolate chip waffles, her favorite. She sat there with her hands at her sides, watching him, not staring exactly, but not alive to the room either. No silly stories, no school-day chatter.

The toaster jumped and he slathered the waffles with butter and syrup and set the plate down in front of her. He sat in his seat to watch. The third chair, Mommy’s place, was still empty. Maybe the doorbell would ring again …

“Eat,” he told her. She hadn’t picked up her fork yet. He cut off a corner of the stack and held it before her mouth. She did not open it.

“No?” he said. He showed her himself, putting the waffles in his mouth, chewing. He tried her again, but her response was the same. A tear slipped from Gary’s eye and rolled down his cheek. He knew by now that something was terribly wrong with his daughter. But he shoved all that aside.

She was here now, she was back.

“Come.”

He walked her upstairs to her bedroom. Gary entered first, Emma stopping inside the doorway. Her eyes looked on the room with something akin to recognition, but more like distant memory. Like the eyes of an old woman returned miraculously to the bedroom of her youth.

“You need sleep,” he said, rummaging through her chest of drawers for pajamas.

She remained by the door, her hands at her sides.

Gary turned with the pajamas in his hand. “Do you want me to change you?”

He got down on his knees and lifted off her dress, and his very modest preteen daughter offered no protest. Gary found more scratches, and a big bruise on her chest. Her feet were filthy, the crevices of her toes crusted with blood. Her flesh hot to the touch.

No hospital. He was never letting her out of his sight again.

He ran a cool bath and sat her in it. He knelt by the edge and gently worked a soapy facecloth over her abrasions, and she did not even squirm. He shampooed and conditioned her dirty, flat hair.

She looked at him with her dark eyes but there was no rapport. She was in some sort of trance. Shock. Trauma.

He could make her better.

He dressed her in her pajamas, taking the big comb from the straw basket in the corner and combing her blond hair down straight. The comb snagged in her hair and she did not flinch or utter a complaint.

I am hallucinating her, Gary thought. I have lost my bearings on reality.

And then, still combing her hair: I don’t goddamn care.

He flipped back her sheets and quilted comforter and laid his daughter down in her bed, just as he used to when she was still a toddler. He pulled the covers up around her neck, tucking her in, Emma lying still and sleeplike but with her black eyes wide open.

Gary hesitated before leaning over to kiss her still-hot forehead. She was little more than a ghost of his daughter. A ghost whose presence he welcomed. A ghost he could love.

He wet her brow with his grateful tears. “Good night,” he said, to no response. Emma lay still in the pinkish spray of her night-light, staring at the ceiling now. Not acknowledging him. Not closing her eyes. Not waiting for sleep. Waiting … for something else.

Gary walked down the hallway to his bedroom. He changed and climbed into bed alone. He did not sleep either. He was waiting also, though he didn’t know what for.

Not until he heard it.

A soft creak on the threshold of his bedroom. He rolled his head and saw Emma’s silhouette. His daughter standing there. She came to him, out of the shadows, a small figure in the night-darkened room. She paused near his bed, opening her mouth wide, as though for a gusty yawn.

His Emma had returned to him. That was all that mattered.

Zack had trouble sleeping. It was true what everyone said: he was very much like his father. Obviously too young to have an ulcer, but already with the weight of the world on his shoulders. He was an intense boy, an earnest boy, and he suffered for it.

He had always been that way, Eph had told him. He would stare back from the crib with a little grimace of worry, his intense dark eyes always making contact. And his little worried expression made Eph laugh—for he reminded him of himself so much—the worried baby in the crib.

For the last few years, Zack had felt the burden of the separation, divorce, and custody battle. It took some time to convince himself that all that was happening was not his fault. Still, his heart knew better: knew that somehow, if he dug deep enough, all the anger would connect with him. Years of angry whispers behind his back … the echoes of arguments late at night … being awakened by the muffled pounding on walls … It had all taken its toll. And Zack was now, at the ripe old age of eleven, an insomniac.

Some nights he would quiet the house noises with his iPod and stare out his bedroom window. Other nights he would crack open his window and listen to every little noise the night had to offer, listening so hard his ears buzzed as the blood rushed in.

He enacted that age-old hope of many a boy, that his street, at night, when it believed itself unwatched, would yield its mysteries. Ghosts, murder, lust. But all he ever saw, until the sun rose again on the horizon, was the hypnotic blue flicker of the distant TV in the house across the street.

The world was devoid of heroes or monsters, though in his imagination Zack sought both. A lack of sleep took its toll on the boy, and he kept dozing off during the daytime. He zoned out at school, and the other kids, never kind enough to let a difference go unnoticed, immediately found nicknames for him. They ranged from the common “Dickwad” to the more inscrutable “Necro-boy,” every social clique choosing its favorite.

And Zack faded through the days of humiliation until the time came for his dad to visit him again.

With Eph he felt comfortable. Even in silence—especially in silence. His mom was too perfect, too observant, too kind—her silent standards, all for his “own good,” were impossible to meet, and he knew, in a strange way, that from the moment he was born, he had disappointed her. By being a boy—by being too much like his dad.

With Eph he felt alive. He would tell his dad the things Mom always wanted to know about: out-of-boundaries things that she was eager to learn. Nothing critical—just private. Important enough not to reveal. Important enough to save for his father, and that was what Zack did.

Now, lying awake on the top of his bedcovers, Zack thought of the future. He was certain now that they would never again be together as a family. No chance. But he wondered how much worse it would get. That was Zack in a nutshell. Always wondering: how much worse can it get?

Much worse was always the answer.

At least, he hoped, now the army of concerned adults would finally screw out of his life. Therapists, judges, social workers, his mother’s boyfriend. All of them keeping him hostage to their own needs and stupid goals. All of them “caring” for him, for his well-being, and none of them really giving a shit.

My Bloody Valentine grew quiet in the iPod and Zack popped the earphones out. The sky was still not yet brightening outside, but he finally felt tired. He loved feeling tired now. He loved not thinking.

So he readied himself for sleep. But as soon as he got settled, he heard the footsteps.

Flap-flap-flap. Like bare feet out on the asphalt. Zack looked out his window and saw a guy. A naked guy.

Walking down the street, skin pale as moonlight, shining stretch marks glowing in the night, crisscrossing the deflated belly. Obvious that the man had been fat once—but had since lost so much weight that now his skin folded in all different ways and different directions, so much so that it was almost impossible to figure out his exact silhouette.

It was old but appeared ageless. The balding head with badly tinted hair and varicose veins on the legs pinned him at around seventy, but there was a vigor to his step and a tone to his walk that made you think of a young man. Zack thought all these things, noticed all these things, because he was so much like Eph. His mother would have told him to move away from the window and called 911, while Eph would have pointed out all the details that formed the picture of that strange man.

The pale creature circled the house across the street. Zack heard a soft moan, and then the rattle of a backyard fence. The man came back and moved toward the neighbor’s front door. Zack thought of calling the police, but that would raise all sorts of questions for him with Mom: he’d had to hide his insomnia from her, or else suffer days and weeks of doctor’s appointments and tests, never mind her worrying.

The man walked out into the middle of the street and then stopped. Flabby arms hanging at his side, his chest deflated—was he even breathing?—hair ruffling in the soft night wind. Exposing the roots to a bad “Just for Men” reddish brown.