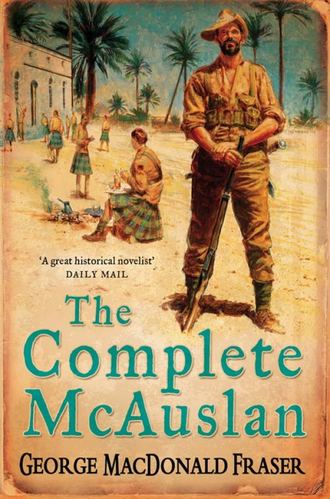

Полная версия

The Complete McAuslan

“Ye’d think you’d paid for it,” said Daft Bob, indignantly. “Honest, sir, d’ye hear him? Ah hate him. I do.”

They snarled at each other, happily, and the quiet Forbes shook his head at me as over wayward children. We refilled the glasses, and I handed round cigarettes, and a few minutes later we were refilling them again, and Leishman, tapping his foot on the floor, was starting to hum gently. McClusky, after an anxious glance at me, took it up, and they sang “The Muckin’ o’ Geordie’s Byre”—for Leishman was an Aberdonian, and skilled in that strange tongue.

“That’s a right teuchter song,” said Fletcher, and gave tongue:

As I gaed doon tae Wilson Toon

Ah met wee Geordie Scobie,

Says he tae me “Could ye gang a hauf?”

Says I, “Man, that’s my hobby.”

We came in quietly on the chorus, which is “We’re no awa’ to bide awa’, we’ll aye come back and see ye,” which Scottish soldiers invariably sing after the first two or three drinks, and which the remnants of the regiment had sung as they waited for the end at St Valery. Then we refilled them again, and while Fletcher and Daft Bob wrangled over the distribution, Forbes asked me with casual unconcern how I was liking the battalion. I said I liked it very well, and we talked of this and that, of platoon business and how the Rangers were doing, and the Glasgow police force and the North African weather. And after a few more drinks, in strict sobriety, Fletcher said:

“We’ll have tae be gettin’ along.”

“Not a bit of it,” I said. “It’s not late.”

“Aye, weel,” said Fletcher, “mebbe it’s no’.”

“Aw-haw-hey,” said Daft Bob.

So another half hour passed, and I wondered how I would find out the answers to the questions which could not be asked. Probably I wouldn’t, but it didn’t matter, anyway. Next day, on parade, Fletcher would be looking to his front as stonily as ever, Leishman would have given several extra minutes’ attention to his rifle, I would be addressing Daft Bob severely, and all would be as it had been—except that for some reason they had thought it worth while to come and see me on Hogmanay. Some things you don’t ponder over; you are just glad they happened.

“You gaunae sit boozin’ a’ night?” Fletcher snapped at Daft Bob. “Sup, sup, sup, takin’ it in like a sponge, I’m ashamed o’ ye.”

“Ah’ll no’ be rollin’ in your gutter, Fletcher,” said Daft Bob. “So ye neednae worry. It’s no’ me Mr MacNeill’ll be peggin’ in the mornin’ for no’ bein’ able tae staun up on parade.”

“Peg the baith o’ ye,” said Forbes. “Ye’re aye greetin’ at each other.”

“Sharrup,” said Fletcher. “C’mon, get the bottles packed up. Let the man get tae his bed.”

Daft Bob and McClusky collected the empties, while Fletcher bossed them, and they all straightened their bonnets, and looked at each other again.

“Aye, weel,” said Forbes.

“Well,” I said, and stopped. Some things are impossible to put into words. “Well,” I said again. “It was great to see you. Thank you for coming.”

“Ye’ll be seein’ us again,” said Fletcher.

“Aw-haw-hey,” said Daft Bob.

“Every mornin’, numbered aff by the right, eh, Heinie?” said McClusky.

“That’s the way,” said Forbes.

“Tallest on the right, shortest on the left.”

“Clean, bright, and slightly oiled.”

“We’re the wee boys.”

“Gi’ the ba’ tae the man wi’ glasses.”

“Here’s tae us, wha’s like us?”

“Aw-haw-hey.”

“Ye gaunae staun’ there a’ night, then?” demanded Fletcher.

“Ah’m gaun. Ah’m gaun,” said Daft Bob. “Night, sir. Guid New Year.” They jostled out, saying good-night and a good New Year, and exchanging their incredible slogans.

“Good night,” I said. “Thanks again. Good night, Fletcher. Good night, Forbes. Good night, D— er, Brown. Good night.”

They clattered off up the corridor, and I closed the door. The room was full of cigarette smoke and bar-room smell, the ash-trays were overflowing, and there was a quarter-full bottle of whisky still on the sidetable, forgotten in the packing. I sat on the edge of my bed feeling about twenty feet tall.

Their feet sounded on the gravel, and I heard Daft Bob muttering, and being rebuked, as usual, by Fletcher.

“Sharrup, ye animal.”

“Ah’ll no’ sharrup. Ah’ll better go back an’ get it; it was near half-full.”

“Ach, Chick’ll get it in the mornin’.”

There was a doubt-laden pause, and then Daft Bob: “D’ye think it’ll be there in the mornin’?”

“Ach, for the love o’ the wee wheel!” exclaimed Fletcher. “Are ye worried aboot yer wee bottle? Yer ain, wee totty bottle? Ye boozy bum, ye! D’ye think Darkie’s gaun tae lie there a’ night sookin’ at yer miserable bottle? C’mon, let’s get tae wir kips.”

The sound of their footsteps faded away, and I climbed back into bed. In addition to everything else, I had found out who Darkie was.

* ile = oil (castor oil).

Play Up, Play Up, and Get Tore In

The native Highlanders, the Englishmen, and the Lowlanders played football on Saturday afternoons and talked about it on Saturday evenings, but the Glaswegians, men apart in this as in most things, played, slept, ate, drank, and lived it seven days a week. Some soldiering they did because even a peace-time battalion in North Africa makes occasional calls on its personnel, but that was incidental; they were just waiting for the five minutes when they could fall out crying: “Haw, Wully, sees a ba’.”

From the moment when the drums beat “Johnnie Cope” at sunrise until it became too dark to see in the evening, the steady thump-thump of a boot on a ball could be heard somewhere in the barracks. It was tolerated because there was no alternative; even the parade ground was not sacred from the small shuffling figures of the Glasgow men, their bonnets pulled down over their eyes, kicking, trapping, swerving and passing, and occasionally intoning, like ugly little high priests, their ritual cries of “Way-ull” and “Aw-haw-hey”. The simile is apt, for it was almost a religious exercise, to be interrupted only if the Colonel happened to stroll by. Then they would wait, relaxed, one of them with the ball underfoot, until the majestic figure had gone past, flicking his brow in acknowledgment, and at the soft signal, “Right, Wully,” the ball would be off again.

I used to watch them wheeling like gulls, absorbed in their wonderful fitba’. They weren’t in Africa or the Army any longer; in imagination they were running on the green turf of Ibrox or Paradise, hearing instead of bugle calls the rumble and roar of a hundred thousand voices; this was their common daydream, to play (according to religion) either for Celtic or Rangers. All except Daft Bob Brown, the battalion idiot; in his fantasy he was playing for Partick Thistle.

They were frighteningly skilful. As sports officer I was expected actually to play the game, and I have shameful recollections still of a company practice match in which I was pitted against a tiny, wizened creature who in happier days had played wing half for Bridgeton Waverley. What a monkey he made out of me. He was quicksilver with a glottal stop, nipping past, round, and away from me, trailing the ball tantalisingly close and magnetising it away again. The only reason he didn’t run between my legs was that he didn’t think of it. It could have been bad for discipline, but it wasn’t. When he was making me look the biggest clown since Grock I wasn’t his platoon commander any more; I was just an opponent to beat.

With all this talent to choose from—the battalion was seventy-five per cent Glasgow men—it followed that the regimental team was something special. In later years more than half of them went on to play for professional teams, and one was capped for Scotland, but never in their careers did they have the opportunity for perfecting their skill that they had in that battalion. They were young and as fit as a recent war had made them; they practised together constantly in a Mediterranean climate; they had no worries; they loved their game. At their peak, when they were murdering the opposition from Tobruk to the Algerian border, they were a team that could have given most club sides in the world a little trouble, if nothing more.

The Colonel didn’t speak their language, but his attitude to them was more than one of paternal affection for his soldiers. He respected their peculiar talent, and would sit in the stand at games crying “Play up!” and “Oh, dear, McIlhatton!” When they won, as they invariably did, he would beam and patronise the other colonels, and when they brought home the Command Cup he was almost as proud as he was of the Battle Honours.

In his pride he became ambitious. “Look, young Dand,” he said. “Any reason why they shouldn’t go on tour? You know, round the Med., play the garrison teams, eh? I mean, they’d win, wouldn’t they?”

I said they ought to be far too strong for most regimental sides.

“Good, good,” he said, full of the spirit that made British sportsmanship what it is. “Wallop the lot of them, excellent. Right, I’ll organise it.”

When the Colonel organised something, it was organised; within a couple of weeks I was on my way to the docks armed with warrants and a suitcase full of cash, and in the back of the truck were the battalion team, plus reserves, all beautiful in their best tartans, sitting with their arms folded and their bonnets, as usual, over their faces.

When I lined them up on the quayside, preparatory to boarding one of H.M. coastal craft, I was struck again by their lack of size. They were extremely neat men, as Glaswegians usually are, quick, nervous, and deft as monkeys, but they were undoubtedly small. A century of life—of living, at any rate—in the hell’s kitchen of industrial Glasgow, has cut the stature and mighty physique of the Scotch-Irish people pitifully; Glasgow is full of little men today, but at least they are stouter and sleeker than my team was. They were the children of the hungry ’thirties, hard-eyed and wiry; only one of them was near my size, a fair, dreamy youth called McGlinchy, one of the reserves. He was a useless, beautiful player, a Stanley Matthews for five minutes of each game, and for the rest of the time an indolent passenger who strolled about the left wing, humming to himself. Thus he was normally in the second eleven (“He’s got fitba’,” the corporal who captained the first team would say, “but whit the hell, he’s no’ a’ there; he’s wandered.”)

The other odd man out in the party was Private McAuslan, the dirtiest soldier in the world, who acted as linesman and baggage-master, God help us. The Colonel had wanted to keep him behind, and send someone more fit for human inspection, but the team had protested violently. They were just men, and McAuslan was their linesman, foul as he was. In fairness I had backed them up, and now I was regretting it, for McAuslan is not the kind of ornament that you want to advertise your team in Mediterranean capitals. He stood there with the baggage, grimy and dishevelled, showing a tasteful strip of grey vest between kilt and tunic, and with his hosetops wrinkling towards his ankles.

“All right, children,” I said, “get aboard,” and as they chattered up the gangplank I went to look for the man in charge. I found him in a passageway below decks, leaning with his forehead against a pipe, singing “The Ash Grove” and fuming of gin. I addressed him, and he looked at me. Possibly the sight of a man in Highland dress was too much for him, what with the heat, for he put his hands over his eyes and said, “Oh dear, oh dear,” but I convinced him that I was real, and he came to quite briskly. We got off to a fine start with the following memorable exchange.

Me: Excuse me, can you tell me when this boat starts?

He: It’s not a boat, it’s a ship.

Me: Oh, sorry. Well, have you any idea when it starts?

He: If I hadn’t, I wouldn’t be the bloody captain, would I?

Now that we were chatting like old friends, I introduced myself. He was a Welshman, stocky and middle-aged, with the bland, open face of a cherub and a heart as black as Satan’s waistcoat. His name was Samuels, and he was not pleased to see me, but he offered me gin, muttering about the indignity of having his fine vessel used as a floating hotel for a lot of blasted pongos, and Scotch pongos at that. I excused myself, went to see that my Highlanders were comfortably installed—I found them ranged solemnly on a platform in the engine room, looking at the engines—and having shepherded them to their quarters and prevented McAuslan falling over the side, I went to my cabin. There I counted the money—it was a month’s pay for the party—and before I had finished the ship began to vibrate and we were away, like Hannibal, to invade the North.

I am no judge of naval behaviour, but looking back I should say that if the much-maligned William Bligh had been half as offensive as Lieutenant Samuels the Bounty would never have got the length of Land’s End, let alone Tahiti. At the first meal in the ward-room—which consisted for him of gin and chocolate biscuits—he snarled at his officers, bullied the stewards, and cross-examined me with a hackle-raising mixture of contempt and curiosity. We were going to the Grand Island, he knew; and what did we think we were going to do there? Play football, was it? Was that all pongos had to do? And who were we going to play, then?

Keeping my temper I told him we had several matches arranged against Service and civilian teams on the island, and he chose to make light of our chances. He had seen my team come aboard; they were midgets, and anyway who had they ever beaten?

At this one of his officers said he had seen us play, and we were good, very good. Samuels glared at him, but later he became thoughtful, applying himself to his gin, and when the meal ended he was still sitting there, brooding darkly. His officers looked nervous; they seemed to know the signs.

Next morning the African coast was still in view. I was surprised enough to ask Samuels about this, and he laughed and looked at me slantendicular.

“We’re not goin’ straight to the Island, Jocko,” he explained. “Got to look in at Derna first, to pick up supplies. Don’t worry, it won’t take long.” He seemed oddly excited, but distinctly pleased with himself.

I didn’t mind, and when Samuels suggested that we take the opportunity to go ashore at Derna so that my boys could have a practice kick-about, I was all for it. He went further; having vanished mysteriously into the town to conclude his official business, he returned to say that he was in a position to fix up a practice match against the local garrison side—“thought your boys might like a try-out against some easy opposition, like; some not bad footballers yere, give you a game, anyway.”

Since we had several hours before we sailed it seemed not a bad idea; I consulted with the corporal-captain, and we told Samuels to go ahead. And then things started happening.

First of all, Samuels suggested we change into football kit on the ship. There was nothing odd about that, but when we went to the baggage room the team’s fine yellow jerseys with the little tartan badge were missing; it transpired that through some inexplicable mix-up they were now in the ship’s laundry, being washed. Not to worry, said Samuels, we’ll lend you some blue shirts, which he did.

He took personal charge of our party when we went ashore—I was playing myself, as it was an unimportant game, and I wanted to rest our left-half, who had been slightly sea-sick. We played on a mud-baked pitch near the harbour, and coasted to a very gentle 7-0 win. Afterwards the garrison team invited us for drinks and supper, but Samuels interrupted my acceptance to say we hadn’t time; we had to catch the tide, or the wind, or something, and we were bundled into the truck and hurried back to the harbour. But one remark the garrison captain let fall in parting, and it puzzled me.

“It’s odd,” he said, “to find so many Scotsmen in one ship’s crew.”

I mentioned this to Samuels, back on board, and he sniggered wickedly.

“Well, now, natural enuff,” he said. “He thought you was all in the ship’s company.”

A horrid suspicion was forming in my mind as I asked him to explain.

“Well, see now,” he said, “I ’ad an idea. When I went ashore first, I looks in on the garrison an’ starts talkin’ football. ‘Got a pretty fair team yere, ’aven’t you?’ I says. ‘District champions,’ says they. ‘Couldn’t beat my ship’s company,’ I says—cuttin’ a long story short, you understand. ‘Couldn’t what?’ says they. ‘You want to bet?’ says I.” He sat back, beaming wickedly at me. “So I got on a little bet.”

I gaped at the man. “You mean you passed off my team, under false pretences … You little shark! You could get the jail for this.”

“Grow up, boyo,” said Samuels. “Lissen, it’s a gold mine. I was just tryin’ it out before lettin’ you in. Look, we can’t go wrong. We can clean up the whole coast, an’ then you can do your tour on the Island. Who knows your Jocks aren’t my matelots? And they’ll bite every time; what’s a mingy little coaster, they’ll say, it can’t have no football team.” He cackled and drank gin. “Oh, boy! They don’t know we’ve got the next best thing to the Arsenal on board!”

“Right,” I said. “Give me the money you won.” He stared at me. “It’s going back to the garrison,” I explained. “You gone nuts, boyo?”

“No, I haven’t. Certainly not nuts enough to let you get away with using my boys, my regiment, dammit, to feather your little nest. Come on, cough up.”

But he wouldn’t, and the longer we argued the less it seemed I could do anything about it. To expose the swindle would be as embarrassing for me and my team as for Samuels. So in the end I had to drop it, and got some satisfaction from telling him that it was his first and last killing as far as we were concerned. He cursed a bit, for he had planned the most plunderous operation seen in the Med. since the Barbary corsairs, but later he brightened up.

“I’ll still win a packet on you on the Island,” he said. “You’re good, Jocko. Them boys of yours are the sweetest thing this side of Ninian Park. Football is an art, is it? But you’re missin’ a great opportunity. I thought Scotsmen were sharp, too.”

That disposed of, it was a pleasant enough voyage, marred only by two fights between McAuslan on the one hand and members of the crew, who had criticised his unsanitary appearance, on the other. I straightened them out, upbraided McAuslan, and instructed him how to behave.

“You’re a guest, you horrible article,” I said. “Be nice to the sailors; they are your friends. Fraternise with them; they were on our side in the war, you know? And for that matter, when we get to the Island, I shall expect a higher standard than ever from all of you. Be a credit to the regiment, and keep moderately sober after the games. Above all, don’t fight. Cut out the Garscube Road stuff or I’ll blitz you.”

Just how my simple, manly words affected them you could see from the glazed look in their eyes, and I led them down the gangplank at Grand Island feeling just a mite apprehensive. They were good enough boys, but as wild as the next, and it was more than usually important that they keep out of trouble because the Military Governor, who had been instrumental in fixing the tour, was formerly of a Highland regiment, and would expect us not only to win our games but to win golden opinions for deportment.

He was there to meet us, with aides and minions, a stately man of much charm who shook hands with the lads and then departed in a Rolls, having assured me that he was going to be at every game. Then the Press descended on us, I was interviewed about our chances, and we were all lined up and photographed. The result, as seen in the evening paper, was mixed. The team were standing there in their kilts, frowning suspiciously, with me at one end grinning inanely. At the other end crouched an anthropoid figure, dressed apparently in old sacking; at first I thought an Arab mendicant had strayed into the picture, but closer inspection identified it as McAuslan showing, as one of the team remarked, his good side.

Incidentally, it seemed from the paper’s comments that we were not highly rated. The hint seemed to be that we were being given a big build-up simply because we were from the Governor’s old brigade, but that when the garrison teams—and I knew they were good teams—got at us, we would be pretty easy meat. This suited me, and it obviously didn’t worry the team. They were near enough professional to know that games aren’t won in newspaper columns.

We trained for two days and had our first game against the German prisoners-of-war. They were men still waiting to be repatriated, ex-Africa Korps, big and tough, and they had played together since they went into the bag in ’42. Some of our team wore the Africa Star, and you could feel the tension higher than usual in the dressing-room beforehand. The corporal, dapper and wiry, stamped his boots on the concrete, bounced the ball, and said, “Awright fellas, let’s get stuck intae these Huns,” and out they trotted.

(I should say at this point that this final exhortation varied only according to our opponents. Years later, when he led a famous league side out to play Celtic, this same corporal, having said his Hail-Mary and fingered his crucifix, instructed his team, “Awright fellas, let’s get stuck intae these Papes.” There is a lesson in team spirit there, if you think about it.)

The Germans were good, but not good enough. They were clever for their size, but our boys kept the ball down and the game close, and ran them into a sweat before half-time. We should have won by about four clear goals, but the breaks didn’t come, and we had to be content with 2-0. Personally I was exhausted: I had had to sit beside the Governor, who had played Rugby, but if I had tried to explain the finer points he wouldn’t have heard them anyway. He worked himself into a state of nervous frenzy, wrenching his handkerchief in his fingers, and giving antique yelps of “Off your side!” and “We claim foul” which contrasted oddly with the raucous support of our reserve players, whose repertoire was more varied and included “Dig a hole for ’im!” “Sink ’im!” and the inevitable “Get tore intae these people!” At the end the Germans cried “Hoch! Hoch!” and we gave three cheers, and both sides came off hating each other.

Present in body and also in raw spirit was Lieutenant Samuels, who accosted me after the game with many a wink and leer. It seemed he had cleaned up again.

“An’ I’ll tell you, boyo, I’ll do even better. The Artillery beat the Germans easy, so they figure to be favourites against you. But I seen your boys playin’ at half-steam today. We’ll murder ’em.” He nudged me. “Want me to get a little bet on for you, hey? Money for old rope, man.”

Knowing him, I seemed to understand Sir Henry Morgan and Lloyd George better than I had ever done.

So the tour progressed, and the Island sat up a little straighter with each game. We came away strongly against the Engineers, 6-0, beat the top civilian team 3-0, and on one of those dreadful off-days just scraped home against the Armoured Corps, 1-0. It was scored by McGlinchy, playing his first game and playing abysmally. Then late on he ambled on to a loose ball on the edge of the penalty circle, tossed the hair out of his eyes, flicked the ball from left foot to right to left without letting it touch the ground, and suddenly unleashed the most unholy piledriver you ever saw. It hit the underside of the bar from 25 yards out and glanced into the net with the goalkeeper standing still, and you could almost hear McGlinchy sigh as he trotted back absently to his wing, scratching his ear.

“Wandered!” said the corporal bitterly afterwards. “Away wi’ the fairies! He does that, and for the rest o’ the game he micht as well be in his bed. He’s a genius, sir, but no’ near often enough. Ye jist daurnae risk ’im again.”

I agreed with him. So far we hadn’t lost a goal, and although I had no illusions about preserving that record, I was beginning to hope that we would get through the tour unbeaten. The Governor, whose excitement was increasing with every game, was heard to express the opinion that we were the sharpest thing in the whole Middle East; either he was getting pot-valiant or hysterical, I wasn’t sure which, but he went about bragging at dinners until his commanders got sick of him, and us.