Полная версия

The Christmas Chronicles: Notes, stories & 100 essential recipes for midwinter

A couple of Novembers ago I was asked to choose the Christmas tree for Trafalgar Square. Well, I helped. We filmed the occasion for television. We had taken the train to Flåm, in Norway, a small village and port at the end of Sognefjord, the world’s deepest fjord. It is easy to worship this landscape, with its crags, forests and crashing waterfalls. By turns lush with forest, or stark in tones of charcoal, grey and white, it is both somehow melancholy and invigorating. The latter especially when you poke your head (stupidly) out of the carriage window and feel the bite of icy air on your face.

By the time we got to Myrdal snow had started to fall. The first that year, each flake as soft and white as goose fat. As the little train arrived in Flåm, the snow turned to heavy, wretched sleet. The crew unpacked their kit with rapidly numbing fingers and filmed for what seemed like hours. They filmed me trudging endlessly through the driving sleet; soaked through to the skin; slipping clumsily on the icy track; barely able to see two feet in front of me; my lips almost unable to move with cold. But mostly they filmed me getting quietly more and more pissed off. Snow is one thing. But driving sleet, especially when you wear glasses, is another thing altogether. I should add that none of that footage ever saw the light of day. Such are the joys of television.

Next morning, we woke to find most of the snow gone, the sun peeping shyly over the mountains, the sky as clear as iced water. We set off for the forest, to find the rangers and, hopefully, our tree. There is nothing accidental about choosing The Tree. You don’t just stumble upon it and think, ‘Oh, that’ll do for Trafalgar Square.’ This is an important tree, an annual gift from the people of Norway each year since 1947, a token of gratitude for our support during the Second World War. Possible candidates are marked when little more than saplings, then monitored for decades. The tree, a Norway spruce, must not be crowded, so lesser examples that get too close are removed, allowing the chosen tree’s branches access to even light, the chance for all sides to grow symmetrically, its trunk to grow straight. As we walk through the forest we spot the trees that might grace Trafalgar Square in 2030 or 2035.

‘Which one do you think is best?’ I am asked. We pick one of the right age, height and girth. It’s a tree casting session. I am given a choice from three or four that have been shortlisted, having been spotted like child prodigies and nurtured towards stardom. The chosen fir has been growing for about seventy years – this we check by drilling a long, pencil-thin sample from its trunk, as a cheesemaker might check the blueing progress of a truckle of Stilton. We count the growth rings one by one.

Next, there follows a phone call to the mayor for permission – a courtesy – then the rangers set about felling. Next time I see it, on the first Thursday in December, the vast tree has been shipped and manoeuvred into position outside the National Gallery and carols are being sung around it by the choir from St-Martin-in-the-Fields, barely a cassock’s throw away. The Norwegian Ambassador is there, as are the mayors of Oslo and Westminster. The tree is lit in traditional Norwegian style, with five hundred simple white lights, its base now garlanded, delightfully, with poems specially commissioned by the Poetry Society.

A few weeks later, just before Twelfth Night, my beloved tree is removed, chipped and composted.

And two sauces for the gnudi

I rescue yesterday’s gnudi from the fridge. I pat them, tenderly, to check their firmness.

Watercress and avocado pesto

avocados, ripe – 2

a lemon

pine kernels – 50g

basil leaves – a handful (about 10g)

olive oil – about 8–10 tablespoons

watercress – 50g

Parmesan (if you wish. I don’t.)

gnudi – 20, small

Halve, stone and peel the avocados. Halve and juice the lemon. Put the pine nuts into a food processor and blend briefly, until they are coarsely crushed, then add the avocados and basil leaves and process, adding as much olive oil and lemon as you need to produce a loose, bright green paste.

Wash the watercress and remove any tough stalks. Grate the Parmesan finely if you are using it.

Bring a pan of water to the boil, deep and generously salted, as you would to cook pasta. Carefully lower the gnudi, a few at a time, into the boiling water. When the balls float to the surface they are ready. This is generally between three and five minutes.

Add the watercress to the sauce, folding it gently through the green paste, then spoon into a serving dish. Lift the gnudi from the water with a draining spoon, place them on the avocado sauce and serve, should you wish, with grated Parmesan on the side.

Spinach and pecorino

spinach – 150g

double cream – 350ml

pecorino romano – 100g, grated

pea shoots – a handful

Wash the spinach and soften it briefly in a large pan with a lid, letting the leaves cook for a minute or two in their own steam, turning them once or twice. When the spinach is bright green and wilted, remove from the pan, squeeze almost dry, then chop it quite finely.

Warm the cream in a saucepan, add the finely chopped spinach and the grated pecorino, then spoon over the gnudi and serve with a scattering of pea shoots.

8 NOVEMBER

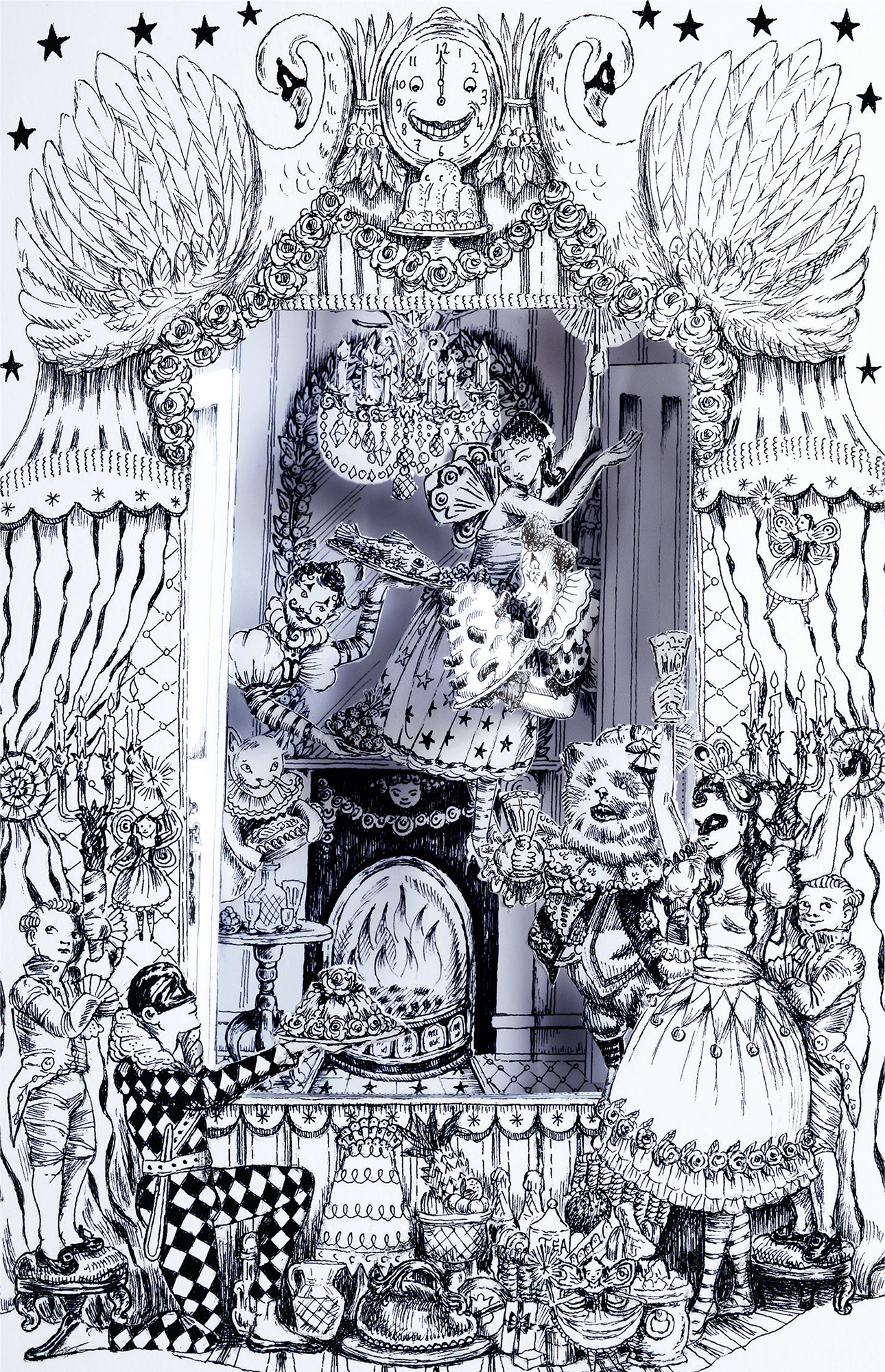

A seat at the pantomime

There are lads in tights, girls in breeches, elderly men with pancake make-up, and bare-chested boys in baggy pants. There are dwarfs and giants, fairies and wizards, a puss in boots and babes in a wood. There are death threats and dreams, genies in lamps, a witch, a princess, and pumpkins that turn into stagecoaches. Pantomime is a gorgeous cacophony of comedy, music, cross-gendering and high jinks.

As a child I was mesmerised by the slightly sinister, dream-like quality that runs through pantomime. I revelled in being slightly scared while all the time knowing I was in a safe place. The cross-dressing, the psychedelic costumes and the sexual innuendo appealed to a boy sitting in the company of the straightest of parents. The colours, comedy and costumes were more of a draw than the stories, which I always found slightly confusing. Take Aladdin. Is it South East Asian, Middle Eastern or East End? Answer, all three.

Most of the political and satirical references were there to amuse the accompanying adults, but not much went over my head. I often found the music terrifying. Especially in Aladdin. Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade has always sent shivers up my spine. I always went accompanied by adults, Mum and Dad, an aunt or uncle. I adored the way that pantomime, like fairy tales, made me comfortably uncomfortable. It has an effect on the imagination no television or film ever could. Although I have to say the slapstick didn’t appeal then, just as it doesn’t now. I have never found people falling over terribly funny.

Pantomime has been with us, in various forms, since the sixteenth century. The version familiar to us is influenced by the Italian Commedia dell’Arte, a style of travelling comedy that moved around Italy and France during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Much of the act was improvised, a comedic performance that involved characters, often masked, always in costume, which we would recognise today. The form took hold in Britain to become Harlequinade, with its main characters being a harlequin, a clown and a pair of lovers.

Panto in Britain was originally, as its name suggests, a mime. Silent comedy performed by mostly French actors escaping their own country’s clamp-down on unlicensed theatres, initially at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and the long-departed Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre. During the nineteenth century, as stage machinery became more sophisticated, the shows became increasingly spectacular. Trapdoors and trick scenery became an essential part of the story, and the slapstick element took hold. Pantomime developed into a cleverly synchronised tapestry of comedy, song, slapstick, mime and satire loosely based around a well-known fairy story.

The titles are firmly established, though new ones come up all the time. Aladdin, Cinderella, Dick Whittington, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Puss in Boots, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Mother Goose and Peter Pan are as popular now as they were a hundred years ago, though each performance will have its own signature. No two versions are alike.

The season for pantomime is short, and tickets sell out like chocolate cake at a village fête. It is now, well before a single mince pie is baked, that you might like to sit down, go online and search what pantos are coming up this year. This may seem all very early, but once word gets round that something is going to be special, seats suddenly disappear.

Tonight, I make a dish of lentils with cream and basil. Essentially a frugal autumn dish, a baked aubergine with a knubbly mound of creamed lentils heady with basil.

Aubergine with lentils and basil

Serves 4

aubergines – 2 large or 4 small

olive oil – 6 tablespoons

a lemon

onions, medium – 2

garlic – 4 cloves

thyme sprigs – 8

rosemary – 6 sprigs

chestnut mushrooms – 200g

Le Puy or other small lentils – 400g

double cream – 250ml

parsley, chopped – 3 tablespoons

basil – a good handful of leaves

Parmesan, grated – 75g

Halve the aubergines lengthways, then score the cut surfaces in a lattice fashion, slicing deeply into the heart of the flesh but without piercing the skin. Place them skin side down on a baking sheet, trickle generously with some of the olive oil, and season lightly. Halve the lemon and squeeze over the juice. Place under a hot grill, a good way from the heat source, and cook until deep golden-brown. The flesh should be soft and silky.

Peel and roughly chop the onions. Warm the remaining olive oil in a shallow pan, then add the onions, stir, and leave them to cook over a moderate heat. Peel and crush the garlic, then stir into the onions. Pull the leaves from the thyme sprigs. Remove the needles from the rosemary, chop finely, then stir, together with the thyme leaves, into the softening onions.

Quarter the mushrooms, combine with the onions and leave to soften and colour. Season with salt and a little black pepper, then leave to simmer, very gently, over a low heat, partially covered with a lid.

Cook the lentils in a saucepan of boiling water for about fifteen minutes, until tender but with a slight nuttiness to them, adding salt about five minutes from the end of cooking. Drain the lentils, then stir into the onion and mushrooms. Pour in the cream, bring to the boil, then fold in the parsley, torn basil leaves and grated Parmesan and check the seasoning. It might need a little more pepper.

Serve the lentils in shallow bowls or plates, with a halved aubergine on top, or two if they are small.

9 NOVEMBER

The Christmas list and a fig tart

The row of notebooks, black, brown, indigo, fat with bookmarks and held together with tape, gets ever longer. The handwritten books where I scribble not just notes and recipes, but my endless, obsessive lists. This morning, while it is still dark, I sit at the kitchen table, get out the current little black book and start this year’s Christmas list.

I have never felt Christmas should be run like a military operation, but I do need some sort of order at this time of year. Life isn’t all art and poetry. There is so much to do and so many details to consider if the season is to be a joy rather than a chore. Occasionally, just occasionally, I need to put my practical hat on. Anyway, I actually like making lists, I have done it all my life. No need to stop now.

There are cards to be bought, gifts to consider, food to prepare and events to be scheduled. No, I don’t know what sort of cheese is going to be on my kitchen table until I go shopping, but I do need to know I have remembered to buy sticky tape. Anyone who has wasted an hour of their life trying to find the bloody Sellotape will know what I mean.

A list, not only written but actually referred to, constantly, like a recipe, will make my Christmas easier. A present list (who will get what). A food and drink list (what will be on the table). The domestic list (is there enough Champagne and coffee beans?). A list of events, teas, and visits to the theatre. Do I need another row of Christmas lights or more candles? If you are the sort of person who makes lists but never looks at them again, fine, it is still worth doing. It will jog your memory. I envy those who feel they don’t need to make any sort of plan and still don’t find themselves short of matches to light the pudding. There is no delight in setting the family’s plum pudding aglow on Christmas Day with a cheap plastic lighter.

Nothing sucks the joy out of receiving a gift than to have been asked, ‘What do you want for Christmas?’ If you know them well enough to ask that question, then you should probably know what they would like anyway. Yes, it’s a practical idea, in as much as you don’t risk disappointing the recipient with the wrong present, but I would rather somebody take that risk than be asked what I want.

My lists will develop slowly over the next couple of weeks, with details added as I think of them. Right now, it’s the basics. I also decide to try out a couple of recipes that may be good to have around over Christmas, and certainly to enjoy over the winter. I start with a sweet tart.

Note to self: buy candles.

Dried fig and Marsala tart

There are two tricky moments in the preparation of any sort of upside-down tart and both involve the caramel. First the making of the sugar and butter sauce without burning or crystallising it, and second, restraining said hot sauce from pouring out over your fingers as you upend the tart on to its serving plate.

The caramel is something I have been playing with, on and off, for years. I have finally decided not to make it in the traditional manner. It is far easier, I find, to make one from sugar and a little sweet wine (in this case Marsala), then drop cubes of butter into it and let everything come together in the oven. The fruit helpfully soaks up most of the caramel, leaving just the right amount of buttery stickiness. Use a tarte Tatin mould or a metal-handled frying pan, or, as I do, a shallow-sided tart tin.

Serves 8

dried figs – 500g

golden sultanas – 50g

dry Marsala – 100ml

golden caster sugar – 100g

butter – 50g

For the pastry:

cold butter – 175g

plain flour – 225g

golden caster sugar – 2 tablespoons

large egg yolks – 2

To serve:

double cream

ice cream

crème fraîche

You will also need a 24cm round Tatin tin or shallow, non-stick cake tin with a fixed base.

Set the oven at 200°C/Gas 6. Put the figs and sultanas into a mixing bowl, pour over the Marsala and leave to stand for forty-five minutes, stirring occasionally.

Make the pastry: cut the cold butter into small cubes and rub into the flour, either with your fingertips or using a food processor. Work until you have what looks like coarse, fresh breadcrumbs. Stir in the sugar.

Add the egg yolks to the butter and flour. Mix together until you have a soft dough, then turn out on to a floured board and knead briefly, for just a minute. Shape the dough into a smooth, fat cylinder. Wrap it in greaseproof paper or clingfilm and leave to rest in the fridge for thirty minutes.

Make the caramel: place the Tatin mould or a frying pan over a moderate heat. (If you will be baking the tart in a cake tin, use a frying pan to make the caramel, otherwise you will damage your tin.) Add the Marsala from the dried fruit, leaving the fruit behind in the bowl, then add the sugar. Bring to the boil and leave to form a thin caramel. If you are using a Tatin mould, remove from the heat. If you are using a cake tin, pour the caramel from the frying pan into the tin.

Cut the butter into small cubes and scatter it over the caramel. Place the plumped-up figs on the base of the tin in a single layer (neatly or not, as you wish), then scatter over the sultanas, pushing them into any gaps.

Roll out the pastry a little larger than the Tatin mould or cake tin. With the help of the rolling pin – it is very fragile – lift the pastry into the mould or tin, pressing it gently into place over the figs. Tuck in any overhanging pastry.

Bake in the preheated oven for about thirty minutes, until the pastry is golden. Remove from the oven and leave to settle for ten to fifteen minutes. Place a large serving plate on top of the tart, then, using oven gloves, hold the tin and plate firmly and carefully turn them over, leaving the tart to slide out on to the plate. Serve warm with cream, ice cream or crème fraîche.

10 NOVEMBER

A sweet preserve with a savoury past

A glossy paste of currants and raisins, brown sugar and cinnamon, mixed spice and citrus zest. There is candied peel, and the comfort of Bramley apples and suet. A preserve, sweet, spicy, fruity, whose history goes back to the Middle Ages, and whose smell is redolent of the happiest moments of my childhood.

One of the more pleasing aspects of social media is learning just how many people still make their own mincemeat. I enjoy seeing (and, if I’m honest, am slightly envious of) their proud results after an afternoon spent stirring dried fruits, apples, cinnamon and cloves in the kitchen. Rows of glossy jars, plump as Friar Tuck, are displayed complete with handwritten labels. Presumably so that, come July, the contents won’t be mistaken for chutney.

Disclosure: I don’t always make my own mincemeat. The romanticism appeals, but in practice I often end up buying it, usually from a posh shop or a village fête. A jar whose contents lie somewhere between the syrupy offerings of commerce and something I could have made myself. The years I do have a go are memorable, not only for the day itself, the smell, the bubbling pot of stickiness, but for the lavishness with which I use the results. Mincemeat for cakes, for sandwiching between slices of hot toasted panettone, for steamed puddings and for baking in crumbly biscuits to be eaten mid-morning with a pot of coffee.

Mincemeat hasn’t always been sweet. The clue is in the name. Early recipes, some of which go back to the sixteenth century, contain minced beef and its fat, vinegar and spices. Our little mince pie seems, at one time, to have been almost entirely savoury. A pasty.

The earliest recipes also bring with them a warm breeze from the Middle East, with their familiar marriage of sweet fruits and meat. Thomas Tusser, chorister, poet, musician, author and farmer, lists a recipe (1557) for mince or ‘shred’ pies that was considered standard Christmas fare. Lady Elinor Fettiplace (1570–1647) describes them in more detail, showing them to be more akin to a pasty, listing mutton and beef suet as well as orange peel, raisins, ginger and mace (a spice I have only ever used in meat terrines: Heaven only knows how old my glass jar in the larder is) and rosewater.

The Good Housewife’s Jewel by Thomas Dawson (1598) tempts its readers with a recipe using deer offal (the ‘umbels’ that gave their name to the phrase ‘to eat umble pie’), salt, cloves, currants, almonds, dates and fat. The mince is baked, then boiled with sugar and spices. A long way from the syrupy jam in the present-day Robertson’s jar.

Mincemeat takes a turn away from its savoury route in the seventeenth century. The writer and poet Gervase Markham, whose most famous work is The English Huswife Containing the Inward and Outward Virtues which ought to be in a Complete Woman (a title for which he surely deserves a bat round the head with a frying pan), has a recipe that is almost entirely devoid of meat. As the preserve continues its journey, it ditches not only the mutton, beef and salt, but also the passing whiff of the Middle East.

By the beginning of the twentieth century the minced meat had departed from most recipes, but the practice of adding beads of grated suet lives on to this day, though most used in commercial preparations is made from hydrogenated fat. As sugar becomes less of a luxury, the filling gets steadily sweeter until we arrive at today’s sugar-laden, glistening goo. Most modern recipes have even ditched the tiny pearl-like nuggets of suet that twinkled in their dark, syrupy depths.

For those of us making our own mincemeat, the difficulty is getting our hands on a decent lump of fresh suet to grate. (Go for the whitest, creamiest beef fat your butcher can offer you.) My feeling is that if you use the packet stuff, creamy white specks in a nostalgic blue, red and yellow box, you might as well buy your mincemeat ready-made.

A classic brandy mincemeat

Today, November 10, I make this year’s batch. It’s a bit late, according to Mary Berry, who recommends a maturing time in the jar of six months. (Delia has kept hers for three years with no ill-effects, as I’m pretty sure my mum did.) Six glistening jam jars sit on the counter, each having had a ride in the dishwasher, then ten minutes in the oven at 180°C/Gas 4 to sterilise them. Their labels are already written, in fountain pen, waiting patiently for my Christmas jam.

Despite the long ingredients list, mincemeat is a doddle. I spend more time weighing the dried fruits, spices and sugar than I do cooking. Even then, the task takes barely an hour. I spin it out because I like the smell that is filling the kitchen. The scent of Christmases, past. Better than that, of Christmas to come.

Makes about 1.5kg, enough for 36 (ish) mince pies

shredded suet – 200g

dark muscovado sugar – 200g

sultanas – 200g

currants – 200g

prunes, stoned – 200g

dried apricots – 200g

cooking apples – 750g

skinned almonds – 50g

a lemon

ground cinnamon – 1 teaspoon

ground cloves – ½ teaspoon

nutmeg, grated – ½ teaspoon

brandy – 100ml

Put the suet, sugar, sultanas and currants into a large saucepan. Roughly chop the prunes and apricots and stir them in. Peel and core the apples, cut them into small dice, then add them to the other fruits. Place over a moderate heat and bring to the boil. Finely chop the almonds, finely grate the zest of the lemon, then stir both into the fruit with the cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg. Squeeze the lemon juice into the mixture and continue cooking for about fifteen minutes. Allow to cool, then stir in the brandy.

Spoon the mincemeat into the sterilised jars, seal with a tight lid and label.

Quince and cardamom mincemeat (without suet)

I feel a little sorry for those impervious to the charm of a mince pie. I want to offer them something. Calling the recipe that follows ‘mincemeat’ is stretching it a bit, but it still contains the fruits and spices of the original (many early recipes include quince in place of apple), and it smells like the classic as it cooks. But it has another appeal, that of no suet, or indeed fat of any kind. Think of it as Christmas jam. The colour is gold rather than black. It is rather good with cheese too, in the way a slice of Cheshire is good with fruit cake. Oh, and can I suggest grinding the cardamom seeds at the last minute – the ready-ground stuff loses all its magic.

Makes 3 × 400g jars

caster sugar – 100g