Полная версия

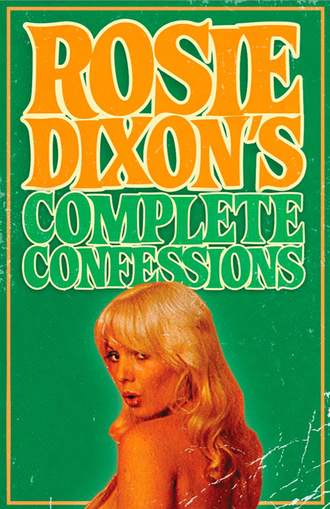

Rosie Dixon's Complete Confessions

“How do they know?” I ask. “I mean, if what you say about men is true a normal woman would get through about a hundred and twenty men in ten minutes.”

“I don’t know how they worked it out,” says Penny. “I think it was a controlled experiment in the States. They fastened electrodes to a couple and told them to make love. Everything was recorded on a seismograph or something like that.”

“I don’t like the idea of that.”

“No, it must take away a bit of the glamour, mustn’t it?”

“I never knew any of this,” I say. “I mean, about orgasms and all that.”

“It’s done more harm than good if you ask me,” sniffs Penny. “A lot of men are getting very worried. It’s bad enough when they get tiddly but when they start worrying about whether they’re going to come up to scratch, that’s even worse. Some of them get so nervous they have a drink to calm themselves down and then they’re twice as badly off. In the old days they used to get on with it without a care in the world and at least you could get something out of them. Now they’re all reading Cosmopolitan and having nervous breakdowns. The only men it’s worth going out with are illiterates—or horsemen like Mark. He never reads anything except Horse and Hound, and they haven’t got on to sex yet—at least, not for humans.”

Poor Jake, I think to myself. I never realised he had so many problems. I wish I could help him with some of them but when he dropped me at the nurses home he said that he did not think he would be able to face me again. I told him to try and keep his pecker up but he started sobbing again and drove off so fast he nearly hit an ambulance.

If the course of true love is not running smoothly for me, there are others who are more fortunate. Old Mr Chapman’s sexy daughter and Jim North the ward wit seem to have struck up an understanding which began when Sonia, that is the daughter’s name, filled up Jim’s stricken fruit bowl with some grapes her old man did not fancy. From this small beginning true love blossoms until Sonia spends more time turning round and talking to Jim than she does rabbiting to her Dad. Not that he notices a lot of difference, poor old devil. He talked to an oxygen cylinder for half an hour on Monday night.

Daily contact with this breathtaking romance is denied me because I find that my name has gone up on the board for night duty. I have been dreading this moment because I fancy staying up all night less than featuring in a marathon dance contest with General Amin. It is not only staying up all night but having to sleep during the day. I can only sleep during the day if I am supposed to be working. Five minutes from Sister Tutor on how to fix up a saline drip for a perforated ulcer and I am drifting off like it is a bedtime story. But, put me in a room with sunlight streaming through the transparent curtains and tell me to sleep and I find it impossible to shut my eyes.

It is not only the daylight. Although there are special rooms provided for Night Nurses to sleep in undisturbed these are always situated above the spot where navvies test their pneumatic drills, maids practise to be the first female town crier and the plumbing makes a noise like a depth charge attack on a submarine.

On the day I am supposed to be preparing to go on night duty, I wish I had gone to a piano smashing festival rather than try and get some sleep.

I am on night duty with a nurse called Cilla Bias and it is not until I see her name written down that I wake up to the fact that her parents could have chosen better. She is far more experienced than me—and has also done a lot more nursing. We are on Fanny Utting which as the name suggests is a women’s ward.

One good thing about nights is that most of the patients have the decency to sleep and you have the chance to write to your Mum and Dad or knit a pair of woolly bedsocks. For the first few nights Cilla chatters on about her life and loves and I try and keep my eyes open. There is a period at about three o’clock every morning when my body feels as if it is leaking away through the floor boards. I don’t think I will ever be closer to death until I am in a coffin. After that the system seems to pick up a bit and soon one is plunged into a whirlwind of activity as one prepares to hand over the patients to the day nurses.

Once one goes on night duty one has joined the enemy. Everything that goes wrong is blamed on the night nurses. All those warning labels I copied out for Sister Bradley were intended to be read by night nurses who would otherwise plunge the whole system into chaos. Every broken thermometer or cracked teacup is blamed on the night nurses. The day sister who takes over from us practically runs into the sluice as if she expects to find the place knee deep in vulture droppings.

Cilla and I are alone on the ward and expected to shout for help if something serious crops up. There is a night sister who is attached to a number of wards and our one reminds me of the ladies in that Wagner music you hear on Two Way Family Favourites—The Ride Of The Val Doonicans or whatever it is. She is a big lady and though she tries to be stealthy her size ten beetle crushers can be heard a couple of wards away. In full flight she looks like a How the West Was Won wagon carried away by the wind.

There are also a number of house surgeons who apportion their presence according to the needs of the patients under their control—e.g. they go to the wards where the nurses are prettiest and provide tea and biscuits. Cilla has a number of admirers and when they are not hurriedly taking their feet off the table in the middle of the ward as night sister crashes into view, she goes and visits them.

Nurse Cilla Bias—or Labby as I find she is called—is no prude when it comes to chucking out details of her love affairs and confides to me that she has indulged in what she calls ‘a stand up quickie’ in one of the private patients’ rooms—when it was unoccupied, I hasten to add. The fortunate recipient of her favours appears to be a houseman called Tom Richmond who plays for the hospital rugby team. He weighs about three tons and I can see why Labby does not want him on top of her—I wonder if she would have been the way she is if she had been called Enid Bias?

The hospital is mad keen on rugby and brain surgeons are second class citizens compared to the likes of Tom Richmond. Medical students are selected more for the size of their muscles than their grey matter and the senior surgeons are more interested in Queen Adelaide’s carrying off the inter-hospital knock-out cup than performing the first underwater heart transplant.

Cilla says that she used to think it was called the knock-out cup because it went to the hospital that knocked out most of the opposition. She says that there is blood everywhere and that before the game everybody parades mascots and pelts each other with bags of soot. It seems pretty daft to me but Cilla says that it is ‘absolutely soopah!’

When Cilla and Tom Richmond start staring into each other’s eyes across the patients’ records I feel about as welcome as honeymoon cystitis and slink away to check the diabetic specimens or perform some other totally unriveting chore. It is even worse when Cilla slips away on one of her little visits because I find it very spooky when I am alone. The only light comes from above the table in the middle of the ward and shines in from the corridor and it is easy to confuse the figures turning in their sleep with somebody moving amongst the beds. Often I have been nearly asleep and woken with a start convinced that there is someone coming towards me. A cold chill will make me turn round quickly to discover—nothing.

Once, when Cilla comes tip-toeing back from one of her trips and rests her hand on my shoulder I nearly jump out of my skin.

Two patients who do not sleep all through the night are Mrs Tiger and Mrs Black. Mrs Black is white and Mrs Tiger is black as Christmas Eve in the coal shed. Mrs Tiger has a bed at the end of the ward by the French windows and Mrs Black sleeps next to her—or rather she does not sleep next to her. Mrs Tiger is a very restless sleeper and mumbles and talks all through the night. To hear her going on sometimes you would think there was actually someone there with her.

“I can’t stand it,” complains Mrs Black, who must be about eighty and not exactly Bamber Gascoyne when it comes to getting it together. “It’s all Black Magic, you know.”

“Giving her an upset tummy, you mean?” I say. “I didn’t think she was allowed chocolates anyway. I’ll tell—”

“No, no, no, silly girl. I mean witchcraft. She’s talking to the spirits of her ancestors. Sometimes they answer her back.”

“Can’t you tell her to talk more quietly?”

“She can’t do anything about it. She’s not in control. She says she’s been taken over.”

“I’ll see if we can give her a tablet,” I say soothingly. “Now you must try and get some sleep.”

“I hope the man doesn’t come tonight.”

“She talks about a man, does she?” I say tucking in the sheets.

“She talks to a man. I saw him once, at the end of the bed.”

Poor old thing, I think to myself. Definitely going soft in the nut. “I’ll give you a tablet, too,” I say.

The next evening, when we come on duty, Sister Belter, the day sister, is bristling like a jelly pincushion. “I don’t know what you two were up to last night,” she says. “But I don’t expect my nurses to have to clear up your litter.”

I don’t know what she is talking about. Perhaps Cilla left a tea cup unwashed. I can see Cilla looking at me and thinking the same thing.

“Bones under the beds,” says Sister Belter. It sounds like the title of a detective story.

“Bones?”

“Chicken bones.” Sister looks us up and down disdainfully.

“I suppose those large frames need some filling.” Sister Belter is a small pinched woman and whoever pinched her could take her back again without any fear of prosecution from me.

“It must have been one of the patients having a midnight snack,” says Cilla. “It wasn’t us.”

“Surely, if you were doing your jobs properly you would be aware of a patient munching chicken. Anyway, the patients all denied that they had eaten anything.”

‘Where did you find the bones, sister?” I ask.

“Underneath Mrs Tiger’s bed. What’s so funny, Nurse?”

“I was just thinking about tigers and bones,” I say trying to keep a straight face.

“I don’t find it a laughing matter, and neither will you if I find any more litter tomorrow morning.”

“I hope she cuts herself shaving,” mutters Cilla as Sister flounces off. “You didn’t have any chicken, did you?” Labby returned flushed and glowing from an hour with Doctor Richmond the previous night and so was not in the best position to keep abreast of all my movements.

“Of course not! I’d hardly be likely to bung the remains under the bed, would I? Sister must be nuts.”

Labby settles down to tell me what happened in the maids’ room on the third floor and I soon forget about chicken bones.

“Aren’t you frightened of someone coming in?” I ask.

Labby giggles. “I was last night. The floor polisher was still plugged in and Tom stood on the control. He said I nearly ruptured him when I jumped in the air. For a moment I thought that great whirring noise was him.”

“How sexy,” I say. “What happened?”

“I had to turn the light on in the end. Tom’s trousers were round his ankles so he couldn’t move and the cleaner knocked him on the floor. The buffing pads ripped his Y-fronts to pieces, so you can see what a good job it was that he was somewhere else at the time. I kicked over half the brooms in the place before I found the light.”

What a boring life I lead, I think to myself. Sometimes I wish I could be footloose and fancy free like some of the other girls in the hospital. Staying up all night would be so much easier if I thought that someone cared for me. At the moment I feel like the female lead’s best friend in an American musical.

It comes as no surprise when Labby asks if I would be an “absolute sweetie” and hold the fort while she pops off to share a few stolen moments with Tom Richmond. Sometimes I wonder who suffers most from their relationship, the patients or the rugby team.

She gets a call at about two in the morning and pads off eagerly leaving me to the gloom and the stirring bodies. I try to read a book but I can’t take in the words and decide to make a tour of the ward.

Mrs Tiger’s mumbling can be heard three beds away. “Oh man, oh man, oh man. Take it away.” She pants as if in a fever. “Take it away!”

Her eyes are closed but her hands are moving down the bedclothes as if pushing something from her. It is all rather spooky and a bit kinky.

I can see Mrs Black’s eye glinting so I go over to her and ask if she is all right. Her back is turned towards Mrs Tiger’s bed and she nods very gently as if not wanting to draw attention to herself. “Always the same. Always talking, they are.”

I imagine that the “they” refers to all the Mrs Tigers in the world but Mrs Black’s next words make me change my mind. “He was here again last night. All the mumbo jumbo. I don’t like it. This is a women’s ward. Why should he come out of visiting hours?”

I should have done something about those pills, I think to myself. I wonder if I dare give her something without consulting anybody?

“It’s very trying,” I say. “But you must try and get some sleep.”

“I’m not going to sleep until the man’s been.”

“There’s no man, Mrs Black. You probably saw one of the house surgeons doing his rounds.”

“We don’t have any blackies. Black as your hat, this one. Scraping away with his sticks.”

Her voice dwindles away but the eye that I can see remains defiantly open. There is no point in talking further so I go back to the circle of light in the middle of the ward. How menacing it suddenly seems. An undefended camp surrounded by darkness. I wonder what the sticks were that Mrs Black was talking about. I can’t think of— and then it comes to me. Bones are like sticks.

I look down the ward and wish that Labby would come back. Even Night Sister would be a welcome visitor at the moment. I feel angry that I should be left alone to shoulder all the responsibility, but most of all I feel afraid.

From where I am sitting I can see Mrs Tiger thrashing in her bed and as I watch, the curtains over the French windows seem to have picked up the motion. I must be dreaming because—no, it can’t be. For an instant I think I can make out a figure standing at the bottom of Mrs Tiger’s bed. I close my eyes and when I open them the figure has gone. The curtains are still moving, though. Funny, because the windows can’t be open although that is what it looks like.

Without really wanting to I leave the imagined safety of the light and walk down the ward. A cold draught meets my face and I can see that the curtains are moving. It must be the wind—unless there is someone standing behind them. The latter thought does nothing to make me quicken my pace and it is in something approaching a panic that I stick out a hand and press the rippling fabric. The French windows are open.

Holding my breath, I go out onto the balcony. It is raining and I can see the drops picked out in the street lamp opposite. There is no sign of anyone. The windows must have been left open when the day nurses went off duty, although it is strange that I did not notice anything when I was talking to Mrs Black.

Feeling relieved and a little foolish, I shut the windows and draw the curtains tight. Mrs Tiger has stopped thrashing about and appears to be sleeping peacefully. She is lying on her back with her hands outside the sheets and resting on her lap.

I turn to go back to my table when my foot strikes something. I know what it is before I look down. A bone. One of a pair lying crossed at the foot of the bed. At the moment my foot touches it Mrs Tiger cries out and begins to stir. I pick up the bones and immediately her movements become more pronounced. The bones look exactly like the ones Sister waved under our noses. I don’t like touching them and drop them on the end of the bed. Immediately Mrs Tiger’s movements become less jerky and her mood calmer. It is as if her actions are governed by the position of the bones and that to interfere with them is to cause her discomfort. Her hands are still moving restlessly up and down her body so I take the bones and my courage in both hands and return the thin splinters to their original position on the floor.

Immediately Mrs Tiger sinks back like a deflated balloon and her hands stop moving. I breath a sigh of relief and see that Mrs Black is watching me.

“Did you see him?” she hisses. “He shouldn’t be here. I don’t want no blackie putting spells on me when I’m sleeping. It’s not nice.”

“I didn’t see anybody,” I lie. “Try and get some sleep. Mrs Tiger is quiet as a mouse.’

“It’s not right, he should come at the same time as the other visitors.”

I leave her muttering about the loopholes in the National Health Service and return to my table just as a ruffled Labby hurries into sight.

“Rosie, guess what happened?” she trills.

“Tom caught his prick in the driving band of a vacuum cleaner?”

I know it is not a very nice thing to say but I am feeling rather overwrought and eager to release tension.

“He asked me to marry him!”

“That’s fabulous but you ought to hear what happened while you were away.”

“I said yes, I thought about waiting until he got a registrar’s job but—”

“Mrs Tiger is being treated by black magic.”

“I didn’t think she was allowed chocolates. What is it? Some new kind of—”

“I’ve been through all that,” I shriek “I mean voodoo, obiah—that kind of black magic. There’s a witch doctor who slips into the hospital and leaves crossed chicken bones at the end of Mrs Tiger’s bed.”

Labby takes a step backwards and puts a hand on my forehead. “Have you been at the brandy again?” Her expression becomes menacing. “Or are you just trying to upstage my greatest moment?”

“Come and see for yourself,” I beg her. “I think it’s smashing about you and Tom and I hope you’ll be very happy,” I give her a kiss on the cheek. “Now come and see these bones. They’re just like the ones Sister found.”

Labby pads along behind me and I can tell that she thinks I am mad or playing a joke. “There you are.”

Labby stares at them sceptically. “I suppose I get an electric shock when I pick them up?”

“You won’t,” I say.

“Well, whatever they are, we can’t leave them there. Sister will go off her teeny rocker.”

Before I can stop her Labby bends down and picks up the bones. Immediately Mrs Tiger gives a yelp and rises up in bed as if hauled by a rope. Labby is so shocked that she drops the bones on the floor and I hurriedly rearrange them in a crossed position. Mrs Tiger sinks back onto her bed.

“Now do you believe me?” I say.

“It’s uncanny,” says Labby. “You’re sure you’re not joking?”

“Don’t be daft. How could I be?”

“I’ll fetch Tom. He’ll know what to do.”

Labby’s faith is touching but Doctor Richmond is reputed to be as thick as a lorryload of sanitary towels and I do not reckon that he is the man to deal with a problem of this delicacy.

“Don’t do that,” I say. “I know exactly what to do: leave the bones where they are.”

“What’s Sister going to say tomorrow morning?”

Labby has a point. I can see the cold light of dawn getting even colder when I start explaining to Sister about rustling curtains and the black man that nutty Mrs Black has seen. Sister will chuck the bones straight into the trash can—probably followed by us. And tomorrow night—Stop! I don’t want to think about it. The witch doctor, or whatever he is, will probably get fed up with people messing around with his chicken bones and turn Labby and me into frogs. Tom is not going to like that—I am not going to like it much, either.

Luckily I have a great idea. “We’ll put them under the floorboards,” I say.

Labby looks from me to the bones to Mrs Tiger and back to me again. “And I thought this was going to be the happiest night of my life,” she says. “You certainly know how to spoil things, don’t you?”

This is a very unkind thing to say but I control myself with difficulty and go and get a teaspoon to prise up the floorboards. Somebody has got to keep cool in this situation.

Ten minutes later I have learned something very useful about hospital cutlery: it is absolutely useless for prising up floorboards. If anyone doubts me I have a collection of mangled knives, forks and spoons to prove it.

“Sister is going to go mad when she sees this lot,” groans Libby. “Let me go and find Tom.”

“Hang on a minute. There must be something we can use.”

Luckily we find a screwdriver that must have been left behind by one of the electricians and, with a crack like my nerves snapping, the floorboard eventually springs into the air.

“Is there room down there?”

“Yes, quick, give me the bones.”

“I don’t want to touch them.”

At that point I say something very unpleasant to Nurse Bias and snatch up the bones. It is as if they are attached to the strings of a puppet because Mrs Tiger immediately starts twitching and groaning. I don’t waste any time but arrange them neatly on a pile of mouse droppings and prepare to replace the board. As I look up I see to my horror that a twenty foot shadow is approaching faSt The shadow is being thrown by Night Sister.

I have already worked out what she is going to say before she looms above me.

“And what do you think you’re doing, Nurse Dixon?”

“I dropped my ring down a crack in the floor, Sister.” I am not usually very good in emergencies and it just shows what a couple of months of hospital life has done for my reflexes.

“You’re not supposed to be wearing jewellery, Nurse.”

“I know, Sister, but I have a great sentimental attachment for this piece. I carry it everywhere with me.”

“Not very securely, obviously.”

“Yes, Sister,” I say meekly. It is always a good idea to give those in authority the opportunity for a sarcastic joke because they can never resist it and it makes them feel much better.

“They were burying the voodoo bones,” pipes up Mrs Black helpfully.

Labby is swift to tap her head and smile sympathetically. “Quite ga ga,” she says.

“Probably as a result of being kept up all night by you two,” sniffs Night Sister. “Hurry up and put that floorboard back and get on with your duties. I don’t know what Sister Belter is going to say when she sees that cutlery.”

Fortunately, Sister Belter never does see the cutlery. Labby and I spend the rest of our spell of duty taking it in turns to race round the hospital replacing individual items so that half the wards end up with a battered memento of the night’s activities.

As regards to Mrs Tiger, she never gives any more trouble and is discharged two weeks later. “Amazing, quite amazing,” I overhear one of the consultants saying. “I never thought she was going to pull through.”

Of course, I am not saying that the chicken bones had anything to do with it but it makes you think doesn’t it?

With Mrs Tiger gone, Mrs Black is entitled to the favoured corner position and I am interested to see what the bones will do for her. The trouble is that she positively refuses to budge.

“I’ll die before I move into that bed,” she says.

Unfortunately, that is exactly what happens.

CHAPTER 8

As I have already illustrated, being on night duty does give the opportunity for hanky panky—for those who like that kind of thing of course—and many of the medics make their rounds with a twinkle in their eye and a twitch in their finger tips. It is amazing how many hands slide round the backs of chairs while patients’ notes are being examined under that shrouded light in the middle of the ward and how close to you the average doctor has to get to be sure that you can both study the same line of print. They are so considerate too, once night falls. It is almost impossible to visit the linen closet without a white-coated attendant eager to suggest new ways of checking that the bedding is soft enough for the patients’ comfort.