Полная версия

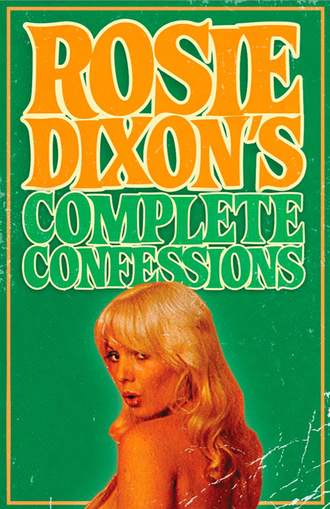

Rosie Dixon's Complete Confessions

“It’s at a place called Little Rogering, not far from Southmouth.”

“Hampshire. That’s nice. That’s where your uncle lives, isn’t it, Harry?”

“He lives near Newcastle,” says Dad shortly. “What’s this school called?”

“St Rodence.”

“Sounds like a rat poison.”

“You’d better not come down, then,” I say. The moment the words have passed my lips I wish I could suck them in again but it is too late.

“How dare you speak to me like that!” bellows Dad. “You go to your room immediately. And stay there until you’re prepared to come down and apologise.”

“I’m sorry, Dad.”

“It’s no good saying you’re sorry now. You go to your room, miss.”

“But you said—”

“Don’t argue with me!”

Considering that I am nineteen it is shocking the way Dad treats me. My younger sister, Natalie, does not have to put up with half of the things that I do. If it was not for the fact that I knew he would take it out on Mum, I would tell the mean old basket what he could do with himself. The only thing I can do is get a job away from home as quickly as possible. St Rodence would be ideal but I wonder if I am good enough to get in. I expect their standards are pretty exacting. Penny’s morals may have been a bit on the easygoing side but I have no doubt that she was quite brainy. She said she was going to send me a prospectus so I will have to wait and see what it says. I will also have to find out what a prospectus is.

I have just gone out into the hall when Natalie comes in wearing her après-school uniform—half a tin of eye shadow and a quart of Californian poppy behind the ears. There are red patches on her throat and it is obvious that she has been snogging. I don’t know why Dad worries about me, really I don’t.

“Oh you’re back,” she says. “I hear there was some trouble.” Hardly through the door and she is on at me. She is her father’s daughter all right.

“Your lipstick is smudged, sister dear,” I say. “Been chasing the grammar school boys on the way home, have you?”

“I’d have brought one home for you if I’d have known you were that interested.” Raquel Welchlet chucks her vanity case on the floor and goes into the front room. “I’m home, Dadsy.”

“Dadsy”! It makes you cringe, doesn’t it? She can wind him round her little finger.

I am halfway up the stairs when the phone rings. I pick it up and put on my most inviting voice. “Hello, Chingford two, three, two, eight.”

“Oh, Mrs Dixon. Is that you?”

I recognise the voice immediately. It is my long time and semi-faithful boyfriend, Geoffrey Wilkes.

“It’s Miss Dixon, actually,” I say coldly. “Is that you, Geoffrey?”

“Natalie? Oh, I’m glad it’s you. I was wondering if you were doing anything tonight? I’ve got a couple of tickets for the professional tennis at the indoor pool.”

I am tempted to suggest that he should dive into the centre of the court from the top board but I control myself. After all, he may be a two-timing creep but he is my boyfriend—when I need him.

“I hate to be a cause of disappointment to you, Geoffrey,” I say, the acid dripping from my fangs. “But this is Rose. Do you remember me? You used to say that I was everything to you.”

I could count to ten while Geoffrey splutters on the other end of the line.

“Rosie? That’s marvellous. Oh—of course—well—I hope you can come—I mean, you can come. I was only asking for Natalie because I thought she’d be able to tell me how you were getting on. I’m always doing it.”

“Always taking Natalie out?”

“No, no, well, there was that once—or it might have been twice, I can’t really remember. We just talked about you and the old times.”

“Like when you made love to her at that party?”

There is more spluttering from the mouthpiece. “Don’t bring that up again. I didn’t know what I was doing.” I can believe that!

“I’ve only just got home,” I say coldly. “I don’t know if I really feel like going out so soon. It seems a bit unkind to the family.”

Dad appears at the door of the front room and waves an arm at me. “I won’t tell you again, my girl. Get up those stairs!”

“Hello? Hello? Are you still there?” Geoffrey is sounding quite worried. Good!

“Sorry, Geoffrey,” I say, calmly. “That was the telly: ‘Family At War’.” Dad looks as if he is going to say something but settles for slamming the door.

“Please come out with me, Rosie. We could have something to eat, as well.”

“I don’t fancy a Wimpy, tonight,” I say. Talk about last of the big spenders. Geoffrey’s idea of giving a girl a good time is to let her have first nibble at his choc ice—he wipes it on his handkerchief afterwards, can you imagine? I don’t want to sound like a gold digger but Geoffrey is tighter than a new roll-on and after asking for Natalie he deserves to suffer a bit.

“I wasn’t meaning a Wimpy,” he says. “I thought we might have a bite up West.”

“The West End?” I say. You have to be careful with Geoffrey. He could be talking about West Chingford.

“Of course. Oh Rosie. Do say you’ll come. You don’t know how much I’ve missed you.”

“You’re sure you wouldn’t rather take out Natalie—or my mother?” Sometimes I am so nasty I amaze myself.

“Rosie! Don’t be like that. We’ll have a great evening. I know we will.”

I don’t mean to be unkind to poor Geoffrey but he is so easy to push around that I can’t stop myself. I am much better with the mean, moody and magnificent types—at least, I would be if I could ever find one. I have not got any nearer than the mean type, so far, which brings me neatly back to Geoffrey.

“Oh, all right, Geoffrey,” I say graciously. “You’ll be round about seven, will you?”

“If that’s all right. Then I can show you my new car.”

“A new, new car?” I ask.

“Oh yes. It’s one of these new Japanese jobs. Goes like a bomb.”

I can remember the last car of Geoffrey’s that went like a bomb—it disintegrated on impact with the road.

“Sounds great, Geoffrey,” I say. “See you later. ’Bye!” I ring off as Natalie comes out of the front room.

“Who was that?” she says.

“Just Geoffrey,” I say, stifling a yawn. “He wants to take me out to dinner and the Wembley tennis.”

“Should be very nice if you don’t mind eating off your knees,” says my revolting little sister. “I had to pack him in. He’s so mean and he only thinks about one thing.”

I ignore her bitchy remarks but at the same time I can’t help thinking about the sex angle. Natalie has suggested before that Geoffrey is a bit of a handful passion-wise. With me he has always acted as if weaned on Horlicks tablets. Could it be that he finds me less desirable than Natalie? Of course, she does behave like a little trollop and wear the most obvious clothes—I will never understand why Mum lets her get away with it—but I would have expected Geoffrey to see through that. Still, he is a man—I think—and they can be very stupid sometimes.

I stick my head round the front room door. “Sorry, Dad,” I say.

Geoffrey arrives just when I knew he would. At ten to seven while I am still in the bath. This is not a great hardship because he goes into the kitchen and helps Mum with the potatoes—I can tell by the peel down the front of his Eastwood Tennis Club blazer. Mum thinks that Geoffrey is the greatest thing to happen to a girl’s marriage prospects since Artie Shaw. She is always telling me what a gentleman he is and what good prospects he has. I think she fancies him a bit, herself.

“Sorry I was a bit early,” he says when I come down at twenty past seven. “Gosh, you do look nice.”

“She’s not a bad looking girl, is she?” says Mum, almost swinging up and down on the bell rope.

“Mum, please!” I say. “Geoffrey, will you look after these, for me?”

Geoffrey pockets my lipstick and compact and leads me out to the car. I must say, it does look snappy. Pillar box red with white wall tyres.

“I can let the seat back a bit if you find it cramped,” says Geoffrey.

“That’s all right,” I say. “Just give me a shoe horn to get in.”

I am not kidding. With both Geoffrey and me inside we have to open one of the windows before the door will shut properly.

“Precision engineering,” explains Geoffrey. “No draughts.”

“You mean, if we have all the windows closed, we suffocate?”

“Not if you remember to switch on the air conditioning.”

“That’s reassuring,” I say. “This wasn’t made by the same firm as the kamikaze planes, was it?”

“I don’t know,” says Geoffrey seriously. “I’ll have to look at the handbook.” Poor Geoffrey. He doesn’t cause Jimmy Tarbuck any sleepless nights.

“I heard a rumour you were giving up nursing,” he says.

“Natalie told you?”

“Well, she sort of mentioned it.”

Typical, I think to myself. I’ll have to wait until Friday to see if she has put an advertisement in the local paper.

“I decided I couldn’t make it my life work,” I say.

“What are you going to do now?”

“I haven’t really made up my mind. I might go into teaching.”

“I hear there’s a big shortage.” Geoffrey makes it sound as if that is my only hope. I think he said the same thing when I told him I was going to become a nurse.

“I think it could be stimulating,” I say.

“I think you’re stimulating.” Geoffreys hand drops onto my knee like a lead spider.

“Keep your hands on the wheel,” I scold, secretly glad that there is asign of red blood coursing through the Wilkes veins.

“It’s not easy,” pants Geoffrey. “It’s been so long.”

I am not quite certain what he is talking about so I don’t pursue the matter.

“We’re going to the tennis first, are we?” I ask.

“I’ve booked a table for ten.”

“But there’s only two of us.”

“I meant ten o’clock,” says Geoffrey.

“I knew you did!” I nearly scream at him. “I was making a little joke.”

“Oh, I see. Yes, very good.”

“Where are we eating, Geoffrey?” I say patiently.

“This new place I was telling you about.”

“I remember that, Geoffrey,” I say grimly. “What is it called?”

“Oh, um, Star of—no. The White—no. It’s somewhere near Goodge Street.”

“You’ve been there?”

“No. A bloke I know told me about it.”

“Can you remember what his name was?” I say sarcastically.

“I think it was Reg Gadney. No, wait a minute, it was—”

“It doesn’t matter.” Honestly, Geoffrey is impossible. I can think of people I have seen on the party political broadcasts who inspire more confidence.

“Don’t worry,” he says. “I’ll recognise it when I see it.”

Unfortunately, Geoffrey reckons without the fiery Latin temperament of one of Stanley Kramer’s tennis stars. He hits a ball at a line judge and it catches Geoffrey smack in the eye. I am furious—Geoffrey’s choc ice goes all over my new skirt—and poor Geoffrey can hardly see anything. His eye swells up and he sits there for the rest of the match with his handkerchief over his face. The officials offer him a free ticket but I can’t see what good it is going to be if he can’t see anything.

Some of these lithe, superbly muscled tennis stars with their film star good looks and brown hairy legs ought to make more effort to control themselves. They may think that they can get away with murder but as far as I am concerned, they are absolutely right. When I look at them and I look at the star of Eastwood Tennis Club I think that Geoffrey would be better off strapping both his tennis rackets to his feet and emigrating to Alaska.

I keep hoping that the player who zapped Geoffrey will come over and apologise so that I can ask for his autograph, but at the end of the game he vaults over the net, punches his opponent senseless and disappears—goodness knows what would have happened if he had lost.

“It’s over now, Geoffrey,” I say. “Are you sure you’re going to be able to see to drive to the restaurant?”

“I think so,” he says. “You may have to help me get the food in my mouth, though.” Geoffrey is very English because he only makes jokes when he is suffering.

The journey to the West End is a nightmare because I can’t drive and Geoffrey has to control the car with one hand over his injured eye and the other changing gear and holding the wheel. I start off by trying to help but when we have driven over the flowerbeds outside the town hall I leave it to Geoffrey. I feel such a fool because he has to cock his head to one side to see properly and I notice the other drivers nudging each other at the lights. They must think I have just socked him one for getting fresh. Fat chance of that!

When we get near Goodge Street it is absolutely hopeless. Geoffrey can’t see anything and can’t remember anything and we drive up endless streets full of parked cars and dustbins.

“You call out the names and I’ll see if any of them rings a bell,” says Geoffrey. “What’s that place over there? ‘Felice’? That rings a bell.”

“Is it a vegetarian restaurant?” I ask.

“No. I don’t think so.”

“Well it can’t be that one. That’s a florist.”

We go on for another ten minutes and I decide I can’t stand it any longer. “Let’s stop anywhere,” I plead. “If I don’t get something to eat in a minute I’m going to start chewing your plastic banana.”

“What?” says Geoffrey, hopefully.

“The thing you’ve got hanging from the rear view mirror.” I tell him. “Come on, this place will do: ‘Borrman’s German Restaurant.’ I’ve never had any German food.”

Well, I can tell you right away. This is not one of my best ideas. The minute the waiter overhears Geoffrey saying that he reminds him of Hitler I know we are going to have problems.

“Ze var is over,” he screams. “Whole generations ov nazis have grown up who av never eard ov concentration camps.”

“Exactly,” I say. “You’re absolutely right. Now, what would you recommend?” You can’t fault me on the humble meter, can you?

Unfortunately, the waiter clearly feels he has an axe to grind. I have noticed before how Geoffrey manages to rub people up the wrong way.

“Recommend?” he shouts. “Vott, you zink zere is something wrong with some ov it? Gott in Himmel, that the Führer should be alive today.” He throws down the menu and we don’t see him again for twenty-five minutes.

“The decor is nice,” says Geoffrey.

“How much longer are you prepared to sit there?” I hiss. “Are you a man or a mouse?”

“Which do you prefer?” says Geoffrey. You know, I really think he means it.

“Tell him we want some food or we’re getting out,” I say. “There’s no excuse for the delay. We’re the only people in the place.”

At first I think that Geoffrey has developed a cold in the throat. Then I realise that his nervous cough is attempting to attract the waiter’s attention. Honestly, talk about an evening with Steve McQueen. I am not surprised that Geoffrey once missed the mixed doubles final because he shut his fingers in his racket press. I am just on the point of taking matters into my own hands when two enormous plates of sausage and red cabbage arrive on the table.

“We didn’t order this,” says Geoffrey.

“‘Order’!? You don’t know ze meaning ov ze vord order,” screams our waiter, fingering his duelling scar. “Ze Panzers, ze knew vot an order vos!” Before we can say anything he sweeps the plates onto the floor and dives behind one of the tables.

“This definitely isn’t the place my friend told me about,” says Geoffrey.

“Don’t be so defensive!” I tell him. “We all make mistakes.”

“Ze died vere ze lay!” screams the waiter. He starts pulling the side plates off the tables and hurling them towards the kitchen.

“Boumf! Boumph!”

“Do you want to stay?” says Geoffrey.

“Are you mad?” I say.

“No, but I’m a bit worried about him.” Geoffrey stands up and clears his throat. “We are leaving now,” he says. He might be repeating “How now brown cow”.

The waiter picks up a knife.

“Come on, Geoffrey!”

“Egon Ronay will hear of this.”

“Geoffrey!” I will remember that terrible man standing at the door and shouting “Schweinhunds!” after us till my dying day—in fact, I thought it was going to be my dying day.

“That was a bit thick,” says Geoffrey as we drive away. “Did you hear what that chap said?”

“Yes. He said ‘Schweinhunds!’”

“No. I mean about reporting us to the Race Relations Board.”

Marvellous, isn’t it? Unless you watched television all the time you could be excused for wondering who won the war.

“I need a drink after that,” I say.

As it turns out, this is my second foolish suggestion of the evening. Spirits play havoc with me on an empty stomach and Geoffrey makes me bolt back a second enormous scotch in order to “get it in before closing time” as he puts it.

“Do you fancy a packet of nuts with it?” he says. “They have eighteen times the protein value of steak, you know?” Something tells me that I can say goodbye to my supper.

“You need a bit of steak for that eye, don’t you?” I say.

“It’s much better now,” says my lark-tongued cavalier. “It’s no hardship looking at you through one eye.”

“You mean, it would be even better if you couldn’t see anything?”

“No! Rosie, why do you have to take everything I say the wrong way?”

“Because that’s the way it comes out,” I say. “Ooooh! I felt quite funny then. I think I’d better sit down.” It must be the scotch.

“I felt funny when you touched my arm like that,” breathes Geoffrey, sinking onto the moquette beside me. “Oh Rosie. I fancy you, rotten.”

“Well, that’s the way I feel at the moment,” I tell him. “I think I’d better go outside.”

“If you want to use the toilet, there’s one in the passage. I saw it as we came in.”

“Thank you, Hawkeye,” I say. “But I don’t think that will be necessary. You’d better take me home.”

We get outside to the car and, thank goodness, Geoffrey’s eye does seem to be a lot better. Just as well because the cool air hits me like a slap in the face and I hardly know what I’m doing.

“Comfy?” says Geoffrey as he shuts the door. “You wait till I turn the heater on. Then you’ll be really snug.”

He is not kidding! After about five minutes I feel as if I am sitting in a microwave oven. Geoffrey is talking to me about teaching but I just can’t keep my eyes open—I believe that lots of people have this trouble with Geoffrey. When I wake up it is because the engine has been turned off.

“Are we home?” I ask drowsily.

“Not quite,” says Geoffrey. “I brought you up to the common because it’s such a beautiful night.”

A glance out of the window shows that Geoffrey is not the only nature lover in North West London. Cars are parked all round us and inside them I can see the shadowy outlines of struggling figures—no doubt fighting to get a better view of the pitch darkness.

“It’s raining,” I say.

“I like rain,” says Geoffrey. “I think it’s very romantic. Water turns me on.” He proves it by trying to slide his hands up my skirt.

“Stop, cock!” I say wittily. “What are you trying to do? I thought you were taking me home?”

Geoffrey transfers his attentions to my breasts and one of my blouse buttons hits the windscreen.

“If you start teaching down in the country I won’t see you,” he pants. “I want you to know how I feel about you.”

“I’ve no problem knowing that,” I say, wishing he could be a bit gentler with his hands.

“Do you remember that time up the tennis club? Let’s do that again.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” I say. Of course, I do remember but I don’t like to think about it. I mean, there was something funny in the fruit cup and Geoffrey took advantage of me—at least, he tried to. I’m still not certain what happened before he was sick behind the roller. As anybody who has read Confessions of a Night Nurse must know I am not a girl of easy virtue who bandies her charms about. I have a romantic nature but I try not to let it go to my head—or anywhere else.

“Just kissing you isn’t going to do any harm.”

Geoffrey is right, of course. There is no sense in being ridiculously prudish. We have known each other for some time and after Natalie’s remarks I am glad to find that I can arouse some feelings in the man. Also, the whisky is making it difficult for me to say no—that and the fact that Geoffrey’s mouth is firmly clamped over mine.

Oh! I wonder where he learned to do that? I always remember Geoffrey as a rather useless kisser. Perhaps Raquel Welchlet has been giving him lessons? The thought makes me determined to demonstrate that big sister knows best.

“Oh, Rosie!” The inside of the windows is beginning to steam up.

“Geoffrey! Please!” Without me realising what was happening he has raided my reception area. How awful that I am so befuddled with drink and hunger that I am practically powerless to resist him.

“That’s nice, isn’t it?”

“Geoffrey!” Now the condensation is running down the windows in rivulets.

“Feel how much I want you.” Geoffrey takes my hand and guides it to—OH! This is too much! Can this be the boy who shyly pressed a cucumber sandwich into my fingers at the Eastwood Tennis Club Novices’ Competition?

“Geoffrey!!”

“I must have you!” Geoffrey presses something between my legs—I mean, presses something situated between my legs—I mean, presses a lever situated on the floor between my legs—and the back of my seat drops down to the horizontal position. Hardly have I realised what is happening than Geoffrey is trying to scramble on top of me. I have never known such a change come over a man. It must have been that German giving him ideas.

“Are you mad, Geoffrey!?” I screech.

“Mad with love!” Somehow—don’t ask me how he manages to do it—the great idiot gets his foot hooked in the driving wheel. The horn lets out a high-pitched shriek—and then refuses to stop.

“Get your foot away!” I shout.

“I have!”

One of the good things about a nurse’s training is that it teaches you how to handle yourself in an emergency: take a long, critical look at the situation and then—panic.

“You’ve turned the ignition on!”

Geoffrey turns off the ignition and immediately the horn stops and smoke starts billowing out of the front of the car. He turns on the ignition and the smoke dies down while the horn starts again.

“Do something!” I scream. All around us I can see people reacting to the noise and one or two cars switch on their lights and start to pull away.

“You’d better get out!” shouts Geoffrey. He is pressing every switch and knob on the dashboard and I hear something making a spluttering noise like a fuse burning down. “The wiring must have shorted,” he yells.

I don’t wait to hear any more but start scrambling out of the car. Unfortunately, for some reason that escapes me, my tights are round my ankles and I am blinded by the headlights of a car that is pulling away. How embarrassing! I try to pull my skirt over my knees and fall down as I hobble towards the protection of some bushes. This is the last time I will ever let Geoffrey Wilkes take me out to dinner.

I have just found myself face to face with a middle-aged man wearing a plastic mac—and, as far as I can make out, nothing else—when I hear a familiar wailing noise. A police car, with light flashing, is bowling over the pot holes. I had only intended to pull up my tights and then return to help Geoffrey but, maybe, I had better wait and see what happens. The police car screeches to a halt beside Geoffrey’s car and two men jump out. The noise of the horn is still deafening and the smoke like that on a Red Indian party line.

Oh dear! One of the policemen has a breathalyser in his hand. I recognise it because I thought it was something else for a minute.

“Don’t do that!” I whisper to the man in the plastic mac. What a disappointing evening this has been. It just shows what happens when you look forward to something too much.