Полная версия

RISINGTIDEFALLINGSTAR

We only play our roles; animals’ fates are our own. The fifteenth-century orator Pico della Mirandola, in his essay ‘On the Dignity of Man’, declared that to be human is to be caught between God and animal: ‘We have set thee at the world’s centre that thou mayest more easily observe what is in the world.’ Five hundred years later, the Caribbean writer Monique Roffey saw that ‘Animals fill the gap between man and God.’ That gap has widened. As John Berger observed, animals furnished our first myths; we saw them in the stars and in ourselves. ‘Animals came from over the horizon. They belonged there and here. Likewise they were mortal and immortal.’ But in the past two hundred years, they have gradually disappeared from our world, both physically and metaphysically: ‘Today we live without them. And in this new solitude, anthropomorphism makes us doubly uneasy.’

We expect animals to be human, like us, forgetting that we are animals, like them. They ‘are not brethren, they are not underlings’, the naturalist Henry Beston wrote from his Cape Cod shack in the nineteen-twenties; to him, animals were ‘gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear … other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth’. That fear we see in their eyes is fear in alien eyes, eyes created for other realms.

Dennis, Dory and I walk on, around the cove. The tide peels back time, revealing frozen expanses of sand and waves of wrack. Skeins of briar and line have twined together like an elongated net constructed to catch primeval fish. I half expect to see a Neolithic family foraging on the beach. The landscape is moonlike, bone-scattered. Sere, stripped back by the winter, pallid and raw. Yet despite the intense cold – so barbarous it becomes a kind of warmth – the shore is full of life.

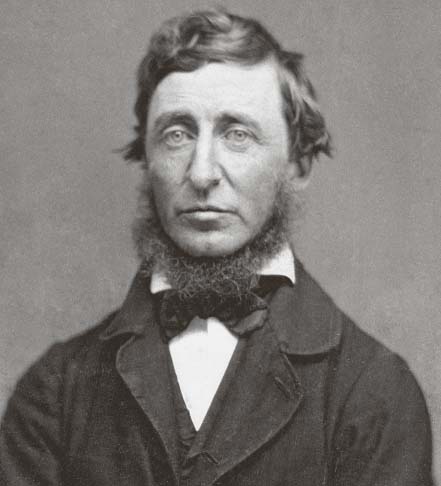

Everything is residual and tentative in the intertidal zone; a place belonging to no one, ‘a sort of chaos’, as Thoreau saw it, ‘which only anomalous creatures can inhabit’. Ribbed mussels, elegantly slipper-shaped in metallic blue and mauve, lie next to tiny flat stones, beige and green and purple and ringed with white. Through this tesserated pavement, samphire pushes up its stiff fingers; it’s called pickle grass here, a name that sums up its salty gherkin crunch. Stattice stands upright; even its everlasting purple flowers have been leached to a lifeless brown. Wind-burnt stalks of wild rose have long since lost their scent, but can still tear bare flesh. Pale-green lichens, barely alive at all, grow infinitesimally, stone flowers in this tundra-by-the-sea.

Dennis shows me his favourite tree: a stunted cedar like a large bonsai, spreading its skirt over a sandy hillock, as though claiming the site of an ancient tumulus. Impaled in a bayberry bush is the empty shell of a crab, probably dropped by a passing gull, still snapping its upraised claws at the sea across the dunes.

The estuary ahead widens with the falling tide. In the distance is Race Point Light. In between is Hatches Harbor, site of another lost settlement, like Long Point. Dennis thinks this was the place known as Helltown – an outpost for the outcasts of an already remote place, the human reverse of this heaven. Perhaps it resembled Billingsgate Island down at Wellfleet, which was reserved for young men, with its own whale-lookout, tavern and brothel.

Today there’s not a soul to be seen on this beach. But one winter morning I arrived here to see what looked like black sails a mile down the shore. As they dipped and swayed, I thought they belonged to particularly intrepid windsurfers. Only when I raised my binoculars did I see that the dark triangles were rising and falling, flexingly powered by something far bigger and stronger than a wetsuited human. I realised, with a sharp intake of cold breath, that they were the flukes of right whales, rolling in the waves.

Trying to remember the intricate geography of this outermost edge of the Cape, I cycled round to the fire road and as far as I could to the distant beach, abandoning my bike in the dunes. I would have run if the sand had allowed me. Cresting a low hill and stumbling through the marran grass, I suddenly regained the shore.

Below me lay a great crescent-shaped arena, occupied by hundreds of herring gulls. As I approached, they rose as one like a theatre curtain to reveal, barely twenty yards beyond the surf, half a dozen right whales engaged in what scientists call a surface active group, and what you and I might call foreplay.

I crouched there, doing my best not to disturb them. For an hour or more I watched their sleek blubbery bodies tumble and turn over one another in an intimate display, all the stranger and more physical for their nearness to the shore, as if they might be beached in the throes of their passion. But nothing could have curtailed those caresses. A harbour seal sat at the waterline watching too, hesitating to share the waves with these loved-up leviathans. It was a spectacle made more extreme by the cold, the sun, the wind and the silence as these gigantic animals, whose glossiness seemed to absorb all the light and the energy of the day, danced around one another in an amorous ballet whose choreography was determined only by their own sensuality.

There are no whales today, amorous or otherwise. Perhaps it is too cold even for their courtship. Dennis and I take shelter in the lee of a dune. For a few moments we’re out of the wind and can draw warm breath again. With the sun on our backs, our muscles relax. Hunched shoulders and curled hands loosen a little. As I look around, I realise that we are surrounded by bones – femurs and sternums, ribs and skulls – all tangled up in the salt hay.

We’re standing in a graveyard, an animal ossuary.

Poking about in the wrack we find a fox splayed in the tousled seaweed as if caught in the act of running, or of agony. Its flesh has been stripped away like an anatomical drawing. Clenched jaws display fine canines; ribs are picked clean. But its brush, the length of its body again, streams behind it, resplendent, rotting.

Nearby is a gannet. Or rather, its wings, six feet wide, great white-and-black contraptions discarded by some modern Icarus who’d fallen face-first into the grainy wet sand, leaving a pair of feet sticking out of the ground. A single gannet would fill my box bedroom back home; a bird on a giant scale. I hold the feathers up behind my back, as if the fledgling buds had burst through my skin, sprouting from my shoulderblades and unfolding to lift me into the air. I remember reading in my children’s encyclopaedia that my dreams of growing functional wings were impossible, because I’d have to grow a breastbone longer than my body. The accompanying illustration showed a man with his sternum hanging down between his legs, like some grotesque man-bird chimera drawn by Leonardo.

We turn back into the wind. The strand sweeps open and wide, connecting the inner bay with the outer sea. A beach that in summer is filled with sunbathers and anglers remains resolutely empty. I take off my clothes – no easy matter with frozen fingers and gloves, hat, scarf, jacket, fleece, two jumpers, boots and socks and jeans and long johns to contend with – and run into the navy-blue sea. It rolls on, and on. It looks like it did six months ago and five thousand years ago. It even feels the same. I treat it accordingly, borne up, singing, as though nothing has changed. As though everything will always be like this, and always was.

It is New Year’s Day.

Dennis and Dory walk on ahead. Glowing pink and shivering like a dog, my extremities as navy blue as the sea, I struggle back into my clothes, unable to do my jacket up with my numb fingers, and run after them. Dory looks back, apparently relieved. Did she think I’d been lost for good? In the car park Dennis has to rub my hands in his, making jokes about hoping that none of his friends will be driving by. My teeth chatter and my muscles shiver, shaking me back to life. Skin and bone burn like a hard cold flame. And they continue to burn and shake for an hour afterwards, till my body is convinced that the threat is over. Every swim is a little death. But it is also a reminder that you are alive.

Out at sea, hundreds of eiders and mergansers bob in the waves. They must be among the most hardy of all animals, these sea ducks, forever riding on the freezing water, resilient and resigned. At the north end of Herring Cove – in the lee of the rip of the Race where the sea turns dark as it becomes the ocean – is a sandbar which traps a temporary lagoon at high tide. In the heat of summer it’s a wonderfully warm place to swim, as languorous as a Mediterranean pool, although once I was horrified to see half a humpback beneath me, its great white knobbly flipper all but waving to me from the sandy bottom, as if its part-carcase were preserved by the salt water. Today the tide is running fast, and would quickly carry me out to sea.

This entire rounded tip of the Cape is a curling catchment, a beneficiary of long shore drift, perpetually shifting to reveal shipwrecks sticking out of the dunes. After winter storms have destroyed most of the car park – leaving its tarmac hanging in slabs like cooled lava over the sand – a chunk of ship, stirred out of retirement, emerges up the beach. Was it washed up or merely uncovered by the storms, lying there all along as I walked there, its knees and ribs beneath me, rubbed and eroded by the decades in which they have rolled around on the sea bed, waiting to be revealed like some vast wooden whale? It might be the remains of a twentieth-century vessel or a Viking longboat. The splintered timbers and curled ribs of oak lie cloaked in emerald-green weed, bolted pieces of something whose shape can only be guessed at.

‘The annals of this voracious beach! who could write them, unless it were a shipwrecked sailor?’ Thoreau wrote as he wandered from one end of the Cape to the other from 1849 to 1857, continually drawn back to this inbetween place. ‘How many who have seen it have seen it only in the midst of danger and distress, the last strip of earth which their mortal eyes beheld! Think of the amount of suffering which a single strand has witnessed! The ancients would have represented it as a sea-monster with open jaws, more terrible than Scylla and Charybdis.’

Walking towards Provincetown, Thoreau saw an arrangement of bleached bones on the beach ahead, a mile before he reached them; only then did he realise they were human, with scraps of dried flesh still on them. It was a sign Shelley had already foreseen, ‘On the beach of a northern sea’, as if in a premonition of his own demise, ‘a solitary heap, | One white skull and seven dry bones, | On the margin of the stones’.

On another walk Thoreau was told of two bodies found on the strand: a man, and a corpulent woman. ‘The man had thick boots on, though his head was off, but “it was along-side”. It took the finder some weeks to get over the sight. Perhaps they were man and wife, and whom God had joined the ocean-currents had not put asunder.’ Like the victims of Titanic, some bodies were ‘boxed up and sunk’ at sea; others were buried in the sand. ‘There are more consequences to a shipwreck than the underwriters notice,’ said Thoreau. ‘The Gulf Stream may return some to their native shores, or drop them in some out-of-the-way cave of ocean, where time and the elements will write new riddles with their bones.’ I see that same sea in his eyes, eyes that seem to see the sea forever; what it had found, and what it had lost.

Nearly four thousand ships have been wrecked along the Cape’s outer shore, from Sparrowhawk, which ran aground down at Orleans in 1626 and whose survivors were given refuge by the Pilgrims at Plymouth, to the British ship Somerset, which came to grief off Race Point in 1778 during the Revolutionary War, having fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill, foundering on the sandy bar off the Race. Twenty-one of its sailors and marines drowned, but more than four hundred were taken prisoner and sent to Boston. The Cape Codders escorting them gave up halfway, possibly worn down by their charges asking, ‘Are we there yet?’ Somerset has appeared every century since, in 1886, 1973 and 2010; a spirit ship, a beached Flying Dutchman. One writer in the nineteen-forties claimed that scores of people had seen ‘ghosts in the vicinity, ghosts of the British sailors’. The ship remains a sovereign vessel; perhaps I ought to reclaim it for my queen.

Meanwhile, many other wrecks lie out there like time machines. Thoreau saw the bottom of the sea as ‘strewn with anchors, some deeper and some shallower, and alternately covered and uncovered by the sand, perchance with a small length of iron cable still attached, – of which where is the other end?’

‘So many unconcluded tales to be continued another time,’ he wrote. ‘So, if we had diving-bells adapted to the spiritual deeps, we should see anchors with their cables attached, as thick as eels in vinegar, all wriggling vainly toward their holding-ground. But that is not treasure for us which another man has lost; rather it is for us to seek what no other man has found or can find.’

Wreckage and the wrecked: they merge into one, a mangling of man and land, of vessel and sea. I think of Crusoe cast up on the shore waiting for Friday’s footsteps, as the waves washed over a plaintive nineteen-sixties soundtrack; of Ishmael, another orphan, clinging to a coffin carved for Queequeg which provided his lifebuoy; of beached whales and beached humans. And I hear my father singing, ‘My bonny lies over the ocean, my bonny lies over the sea, my bonny lies over the ocean, O, bring back my bonny to me.’ I used to hear ‘body’ for ‘bonny’.

When Thoreau was visiting the Cape, an average of two ships every month would be lost in winter storms, especially on the deceptive bars off the Race at Peaked Hill, where shoulders of sand shadow the ocean’s edge. The roaring breakers catch white on the shifting shelf, luminous at night with the memory of the lives they’ve taken. And all this happened within sight of land.

‘Ship ashore! All hands perishing!’

These tempests were not conjured up by a magician, nor were there any sprites on hand to guide the survivors to safety. Commonly, sailors did not learn to swim – partly through superstition – ‘What the sea wants, the sea will have’ – and partly through practicality, knowing that adrift on the open ocean, their flailing would only prolong their fate. Any attempts to save the shipwrecked were often defeated by the elements. Would-be rescuers could only look on and wait until the storms subsided, by which time it was too late. All that was left to do was to salvage the wreck. In the eccentric museum at the Highland Light, housed in a 1906 hotel standing in the shadow of the lighthouse on the windblown headland, one of the most haunted places I have ever visited, a row of assorted chairs from many different disasters stands as a testimony to lost souls and salvaged domesticity: a sad line of mismatched seating, ranged along a wall at a students’ party. Upstairs, rooms with stable doors lined along a long, narrow and dimly-lit corridor; they still seemed filled with fitful guests, and something in the darkness down the end told me to get out.

Those who did make it ashore could die of exposure in this no-man’s-land, with no hope of reaching dwellings set deep inland, far from the raging sea. In 1797 the Massachusetts Humane Society set up ‘Humane-houses’, a series of huts equipped with straw and matches to provide survivors with warmth and shelter. Their echoes remain in the shacks still scattered through the dunes: rough constructions put together from grey beach-wood and timbers as though assembled by those lost sailors. Even in the town, salvaged ships’ knees propped up houses against the storms that brought the flotsam here, while Thoreau recorded fences woven with whale ribs.

Other dangers lurk in these countervailing waters, seen and unseen. Locals told Thoreau there was ‘no bathing on the Atlantic side, on account of the undertow and the rumour of sharks’, and he was warned by the lighthouse keepers at Truro and Eastham not to swim in the surf. They would not do so for any sum, ‘for they sometimes saw the sharks tossed up and quiver for a moment on the sand’. Thoreau doubted this, although he did see a six-foot fish prowling within thirty feet of the shore. ‘It was of a pale brown color, singularly film-like and indistinct in the water, as if all nature abetted this child of ocean.’ He watched it come into a cove ‘or bathing-tub’, in which he had been swimming, where the water was just four or five feet deep, ‘and after exploring it go slowly out again’. Undeterred, Thoreau continued to swim there, ‘only observing first from the bank if the cove was preoccupied’.

To the philosopher, this back shore seemed ‘fuller of life, more aërated perhaps than that of the Bay, like soda water’, its wildness lent an extra charge by that sense of life and death. Down at Ballston Beach, where Mary and I often swim out of season while seals and whales feed just off the sandbar, the powerful undertow seeks to pull us out. Not long ago a man swimming here with his son was bitten by a great white shark. Public notices instruct swimmers to avoid seals, the sharks’ true targets. Recently a fisherman showed me a photograph on his phone, taken at Race Point. A great white breaks the surfline, barely in the water, with its teeth around a fat grey seal. I place my quivering body in that tender bite, the ‘white gliding ghostliness of repose’ which Ishmael discerned, ‘the white stillness of death in this shark’. I still swim there, despite Todd Motta’s warning, ‘You don’t wanna go like that.’ The water is as hard and cold as ever. But one day, I think, I will not come out of it.

In his book The Perfect Storm, the story of a great gale which hit New England in 1991, Sebastian Junger details the way a human drowns. ‘The instinct not to breathe underwater is so strong that it overcomes the agony of running out of air.’ The brain, desperate to maintain itself to the last breath, will not give the order to inhale until it is nearly losing consciousness. This is the break point. In adults, it comes after about eighty seconds. It is a drastic decision, a final, fatal choice – like an ailing dolphin deciding to strand rather than drown because of something deep in its mammalian core; ‘a sort of neurological optimism’, as Junger puts it, ‘as if the body were saying, Holding our breath is killing us, and breathing in might not kill us, so we might as well breathe in.’

Drawing in water rather than air, human lungs quickly flood. But lack of oxygen will have already, in those last seconds, created a sensation of darkness closing in, like a camera aperture stopping down. I imagine that receding light, being drawn deep, caught between the life I am leaving and the eternity I am entering. We know, from those who have come back from death, that ‘the panic of a drowning person is mixed with an odd incredulity that this is actually happening’. Their last thoughts may be, ‘So this is drowning,’ says Junger, ‘So this is how my life finally ends.’

And at that final moment, what? Who will take care of my dog? What will happen to my work? Did I turn the gas off? ‘The drowning person may feel as if it’s the last, greatest act of stupidity in his life.’ One man who nearly drowned, a Scottish doctor sailing by steamship to Ceylon in 1892, reported the struggle of his body as it fought for the last gasps of oxygen, his bones contorting with the effort, only to give way to a strangely pleasant feeling as the pain disappeared and he began to lose consciousness. He remembered, in that instant, that his old teacher had told him that drowning was the least painful way to die, ‘like falling about in a green field in early summer’.

It is that euphoria which offers an aesthetic end, leaving the body whole and inviolate, a beautiful corpse, as if the sea might preserve you for eternity. There is an inviting compulsion about falling into the sea, because it seems such an unmessy, arbitrary way to go. You’re there one minute, in another world the next; a transition, rather than a destruction.

On his journey from New York to England in 1849 on the ship Southampton, Melville saw a man in the sea. ‘For an instant, I thought I was dreaming; for no one else seemed to see what I did. Next moment, I shouted “Man overboard!”’ He was amazed that none of the passengers or sailors seemed very anxious to save the man. He threw the tackle of the quarter boat into the water, but the victim could not, or would not, catch hold of it.

The whole incident played out in a strange, muted manner, as if no one really noticed or cared, not even the man himself.

‘His conduct was unaccountable; he could have saved himself, had he been so minded. I was struck by the expression of his face in the water. It was merry. At last he drifted off under the ship’s counter, & all hands cried, “He’s gone!”’

Running to the taffrail, Melville watched the man floating off, ‘saw a few bubbles, & never saw him again. No boat was lowered, no sail was shortened, hardly any noise was made. The man drowned like a bullock.’

Melville learned afterwards that the man had declared several times that he would jump overboard; just before his final act, he’d tried to take his child with him, in his arms. The captain said he’d witnessed at least five other such incidents. Even as efforts were made to save her husband, one woman had said it was no good, ‘& when he was drowned, she said “there were plenty more men to be had.”’

Half a century later, in 1909, Jack London – who was a deep admirer of Melville – published Martin Eden, his semi-autobiographical account of a rough young sailor who becomes a writer. London, the son of an astrologist and a spiritualist, was born in San Francisco in 1876. He had led an itinerant life as seaman, tramp and gold prospector. He was a self-described ‘blond-beast’, a man of action, the first person to introduce surfing from Hawaii to California; he also became the highest-paid author in the world with books such as The Call of the Wild, The Sea-Wolf and White Fang. But the proudest achievement of his life, he said, was an hour spent steering a sealing ship through a typhoon. ‘With my own hands I had done my trick at the wheel and guided a hundred tons of wood and iron through a few million tons of wind and waves.’

London wrote Martin Eden while sailing the South Pacific, trying to escape his own fame; the New York Times had reported FEAR JACK LONDON IS LOST IN PACIFIC when he didn’t arrive as expected at the Marquesas, the remote islands where Melville himself had jumped ship in 1840. In London’s book, Eden, the first man to himself, cynical about his new-found celebrity, contemplates suicide in the early hours of the morning. He thinks of Longfellow’s lines – ‘The sea is still and deep; | All things within its bosom sleep; | A single step and all is o’er, | A plunge, a bubble, and no more’ – and decides to take that step. Midway to the Marquesas, he opens the porthole in his cabin and lowers himself out.

Hanging by his fingertips, Eden can feel his feet dangling in the waves below. The surf surges up to pull him in. He lets go.

Everything in his strong constitution fights against this act of self-destruction. As he hits the water, he begins to swim; his arms and legs move independently of his will, ‘as though it were his intention to make for the nearest land a thousand miles or so away’. A tuna takes a bite out of his white body. He laughs out loud. He tries to breathe the water in, ‘deeply, deliberately, after the manner of a man taking an anaesthetic’. But even as he pushes his body down vertically, sinking like ‘a white statue into the sea’, he is pushed back to the surface, ‘into the clear sight of the stars’.