Полная версия

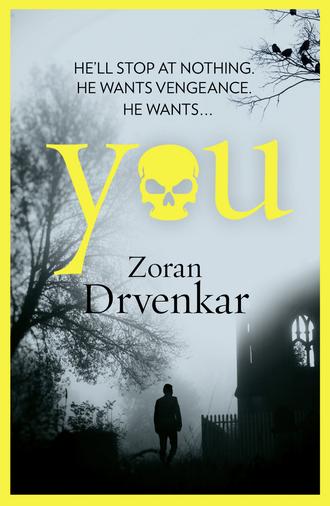

You

“M-M-Mirko.”

“Hi, Mirko, you’ve got half an hour to save your life.”

MIRKO

A wood louse hides under a stone. That’s exactly how it is. You’re the wood louse, the stone’s a car that you’ve squashed yourself under as if the sky was about to cave in on you. If someone tells you right now that Darian’s father will be standing beside you in three days’ time, giving you half an hour to save your life, you’d probably never come out from under that car. You’ve not met Ragnar Desche until then. He’s a legend, he’s a ghost and the father of your best friend. Nobody talks about Ragnar Desche. Never. Even thinking about him is taboo. Or as Darian once said: If my father wants, I’m dead within a second.

There’s a nasty taste in your mouth, sweet and metallic, as if you’d bitten off some chocolate without taking off the silver paper. You spit, see the red stain on the tarmac and swallow down your own blood.

You ran away. That’s it. The end.

I know.

How could you run away? Only an idiot would run away. You’re the idiot. And what are you going to do now? You can’t just stay under the car hiding. You just can’t do that. Somebody will find out. These things always come out.

The wood louse rolls aside and pulls itself up by the door handle, it crouches beside the car, back to the driver’s door, head thrown back so the blood doesn’t drip from its nose. You know if the car alarm goes off the wood louse will have a heart attack and piss its jeans.

It’s staying quiet.

You breathe out and look at the other side of the street.

It’s staying quiet.

The derelict house makes you think of a rabid dog that’s just waiting for you to make a false move. Lurking and rigid. Five lamps from the building site are flashing orange lights and illuminating the façade with a flickering light. It’s one of those ruins that you loved as a child. Graffiti on the walls, not a soul to be seen and hidden treasures everywhere. You’re not a child anymore, you don’t find ruins exciting anymore. It’s eleven at night and the city is a greedy hand hovering over you, wanting to stuff you into the darkest hole of the building site.

You rub the blood from your nose and wonder why no one’s followed you. Things don’t get sadder than this. No one’s interested in you. They wanted Darian. They’ve got Darian.

Shit.

“What am I …”

Your voice is a croak. You’re not great at talking to yourself. In horror movies the victims eventually start talking to themselves so that the viewer knows things are turning serious. Nothing serious is happening here, you’re miles away from serious.

How could I have run away?

Your tongue checks if you’ve got a loose tooth. You’re relieved, all your teeth are in place. And your nose isn’t even broken. You banged it when you crawled under that car. A wood louse through and through. You shake your head to get your brain back in gear. You have to do something, doesn’t matter what, you have to do something, otherwise you won’t be able to look at yourself in the mirror again for the rest of the year.

Think.

A few bicycles are parked beside the church, you start tugging away at one of them, kicking the pedals. The chain snaps with a crack, your hands are bruised but hey, you’ve got the fucking chain.

“Okay, okay, okay …”

You wrap one end firmly around your fist and let the chain dangle against your thigh, then you pull yourself together and cross the street.

Whatever happens, one thing is certain, no one’s going to be expecting you.

Darian sits in the ruins on an upside-down plastic barrel, staring into the distance. Elbows on his knees, hands slack. He reminds you a bit of a drawing in a book. Hercules sitting on a rock after a great battle, taking a break. Darian doesn’t look up when you approach, and for a moment you’re sure he’s crying.

“Everything all right?”

Darian raises his head. There’s a bloody scratch above his left eye, and his lower lip looks as if he’s had a collagen injection. There’s a second scratch on his upper arm, the muscles stand out angry, his T-shirt is a tight fit. It’s a mystery to you how anyone would dare to mess with Darian.

“What’s with the bike chain?” he asks, and his words sound as if he’s got a pillow in his mouth.

“Sorry,” you say and drop the chain.

And then there you stand, and there lies the chain at your feet, and there sits Darian who looks at you and says, “You ran away, right?”

You lower your head, you turn red.

“These jerks,” says Darian, and lets you off the hook. “Look at my face, you see that?”

You lean forward and look at his face. Yes, you see it.

“I’m gonna kill them for that,” he says. “And now …”

Darian holds his hand out to you. He doesn’t have to say anything, you open your belt and take off your jeans. It’s the least you can do for him. You’re lucky he doesn’t hit you. It would have been okay, he could even have whipped you with the bike chain, no problem, wood lice can cope with that kind of stuff.

Your jeans are too short, they stick to Darian’s legs like a second skin, he can’t fasten the top button, abs of titanium, thighs of steel. Since he filled the basement with dumbbells and an exercise machine, you’d been down there with the guys two times, but you’d had enough very quickly. Your body is your body, and that’s how it’s going to stay. Even if you wouldn’t have objected to an extra pound of muscle. Training is everything is Darian’s motto. No wonder he fucks the girls left and right.

“First they kick the shit out of me, then they steal my pants. You think that scares me?”

No, you don’t think anything scares Darian. Apart from his training, he goes to the gym on Adenauer Platz twice a week, takes protein supplements, and looks as if he’s in his mid-twenties when in fact he’s only seventeen.

“That doesn’t worry me, because I know exactly who did it.”

Darian thinks it was the Turks, you mumble something about how yeah, it definitely was the Turks. You both know the Turks had nothing to do with it. Not the Turks, not the Yugos, not the gang from Spandau, not even those idiots who have taken over the Westend and nobody knows if they come from Poland or Romania.

Darian goes on.

“You should have heard them. They laughed. I swear, they’re never going to laugh like that again. Just wait. I’m going to turn them inside out. I’ll get them, just you wait.”

“Perhaps you should—”

“Don’t say it,” he cuts in.

“I’m just thinking.”

“Mirko, shut your trap!”

You shut your trap. Darian’s very sensitive about his old man. He’s the only boy in the whole of Berlin who’s regularly made a target because of his old man. Like last night. Not for the Turks, not for the Yugos, but for six guys from the neighborhood. Darian’s a challenge. How far can you go before the gods get furious?

“What are you going to tell him if he asks?”

“My father won’t even notice.”

“But what’ll you say if he does?”

“That I had trouble with a few idiots, that’s all.”

You nod; one word to Darian’s dad and those guys would vanish from the city never to be seen again. That’s what they say.

Darian spits.

“I have my pride, you understand? I have my own pride. I don’t need my father to wipe my ass. So they can work me over, they can drop by every day. It’s called learning the hard way, get me? They want a mean dog, I will be a mean dog. I memorized their faces. One day I’ll be ready for them and then they’ll pay. Mirko, I tell you, they’ll pay.”

Today was your first official appearance. Darian went with you to the Columbiadamm to meet Bebe and his people. Bebe has twenty-four gambling places scattered around Berlin, which he inherited from his family. Darian’s incredibly envious of Bebe. You spent two hours listening to them trying to outdo each other’s successes. In the end Bebe said he was going to send a few girls onto the street while there was still a bit of summer left. Darian couldn’t match that one, and mumbled that he’d better be going. It was just after ten, and during that time you hadn’t learned anything new. Except if you have a dick you have to swing it around. You like learning new stuff.

When Darian and you left the subway, they were waiting. They came up to you, two in the middle, two on the left and two on the right. Darian didn’t hesitate for a second, he shouldered the two guys in the middle aside and made a run. You were right behind him. Through the streets, through the backyards to the ruin, because Darian knows his way around the ruin. How was he supposed to know that the ruin wasn’t exactly undiscovered territory for these six guys?

You wait at the traffic lights for a moment and jump a red. You’re glad it’s late. It wouldn’t be funny if anyone saw you in your stupid underpants. Trainers, white socks and blue underpants with white clocks on them. A Christmas present from your mother.

Darian asks for the fourth time why you always have to wear jeans. Tracksuit bottoms would be a lot more comfortable. You don’t know what to say. In a tracksuit you look like a guy who wants to play football.

“Jeans give you cancer,” says Darian.

It’s a typical Tuesday evening, there’s nothing going on on your street, the usual two drunks are standing outside the falafel shop and whistle after you. The falafel shop is open until two, and until two they won’t budge from the spot. Whatever the weather, those two drunks are always there.

Outside your front door Darian whacks you on the back of the head.

“Hey, pal, still there?”

“Yeah yeah.”

“You’ll get your pants back tomorrow. And keep your mouth shut.”

“Okay.”

“I mean it.”

“I know.”

He doesn’t want to go, he still wants something from you. You feel the tension in your shoulders, as if you are going to have to dodge another blow.

“Is everything okay between us?”

“Of course.”

“We stand up for each other, Mirko.”

“I know.”

He makes a fist, you make a fist, when your fists meet you look at each other and Darian says, “Glad we’ve sorted that out.”

“We did.”

“And think about tracksuit bottoms.”

“If I wear tracksuit bottoms I look like I’m on my way to play football.”

“You have a point there.”

“Thanks.”

“Say hi to your mom.”

“I will.”

“See you tomorrow, then.”

“See you tomorrow.”

After you’ve crept into the apartment, you creep on into the bathroom and wash your face. You turn on the shower and sit motionlessly on the edge of the tub, as if someone had removed your batteries. Every now and again you pass your hand through the running water. Your head is absolutely empty, the pain in your nose a dull thumping. The hiss of the shower calms you down. It’s like a movie that you can watch as often as you want. And if you stretch your hand out, it gets wet and you’re part of the movie.

You get into the shower. You scrub the panic off yourself and enjoy the water on your back. The hammering on the bathroom wall tears you from your thoughts. You turn the water off, rub yourself dry, and wrap the towel around your hips.

“Why do you have to shower so late?”

Your mother is lying on the sofa in the living room, romantic novel in her lap, cigarette in her left hand, right hand where her heart should be. Her question is one of those questions that don’t need an answer. You say hi from Darian and go into your room. You shut the door behind you, let the towel fall to the floor, and get dressed as if the day had only just begun. You are still disappointed in yourself. It was wrong to run away. Darian will never forget that. Lucky nobody else was there. Imagine one of the guys witnessing your cowardice. Whichever way you look at it, you know you have to make it good again.

Somehow.

The smell of falafel and cigarette smoke drifts in through the window, the voices of the two drunks are clearly distinguishable from each other and sound hoarse. Some nights your mother goes down and complains. You live on the second floor, you’re the only ones who complain. The drunks laugh at you.

You button your shirt; your hands are still dirty from the oil on the chain, it’ll take a few days to come off. It looks as if the cops have taken your fingerprints. You check your watch. Uncle Runa will kill you. If you don’t show up at the pizza stand before midnight, you might as well stay home. Your uncle was expecting you an hour and sixteen minutes ago. You wish you were Darian. The kind of person who doesn’t get bossed around. Apart from tonight, tonight he sure got bossed around, you think, and are immediately ashamed of the thought.

There are no customers about. Not even an exhausted taxi driver taking a break and giving his hemorrhoids a rest. The night buzzes with insects. On the other side of the street people are sitting outside the cafés. Laughter every now and again, the scrape of chairs when someone stands up. You wish you were on that side. The telephone booth next to the café is like a yellow eye that flickers irregularly, blinking nonsensical messages at you.

Uncle Runa leans against the battered freezer and stares across at the cafés as if they were his very private enemies. He doesn’t understand how four cafés can open up on one corner. There are lots of things your uncle doesn’t understand. He wears a white apron and a red T-shirt with a silver Cadillac on the front. The T-shirt is tucked into his trousers, his belly hangs over the belt. You have no idea why he can’t wear normal clothes. He isn’t twenty years old anymore, he’s in his mid-forties and acts like he knows what’s cool. He should ask you. You know what’s cool, because you’re the opposite of cool.

“What are you doing here?” your uncle asks and spits between his front teeth. When you were six he wanted to teach you how to do it. The brilliant art of spitting. You never got the hang of it, so he called you a loser. Uncle Runa likes to say that he feels guilty about your father, and that’s why you’re allowed to work for him. He’s doing you a favor. Which doesn’t stop him paying you only six euros an hour. From ten in the evening until four in the morning you take charge of the pizza stand, and then you fall into bed or you’re so wired that you stay up all night and fall asleep in class. It’s been going on for three months. You’d rather be roaming the clubs with Darian, selling grass and pills. But no one respects you yet. You’re still no one.

“Tell me, shitface, what are you doing here?”

Uncle Runa goes through the same routine every time you turn up late. There are no variations, always the same pissed-off face as if he’d stood in a pile of dog shit with your name on it. A train goes over the bridge. When it’s quiet again, you mumble, “Sorry I’m late.”

“What happened to your hands?”

You hide your filthy fingers behind your back.

“Your mother’s a good woman, you know that?”

“I know.”

Suddenly Uncle Runa explodes, as if you’d claimed the opposite.

“You never say a word against your mother, you hear me? Your mother’s an angel! Don’t you dare say anything against your mother! Your father is a son of a bitch! You can say whatever you like about him.”

“He’s also your brother—”

“That’s how come I know he is a son of a bitch!”

Uncle Runa falls silent again.

“How else do you think I know, eh?”

He looks over his shoulder at the clock. You know he has a thing going with your mother. The way he touches her and how they kiss when they meet, the way he’s sometimes sitting in your kitchen in the morning as if he’s been there all night. You’re sure your mother doesn’t hit the bathroom wall when Uncle Runa spends too much time in the shower. His dressing gown hangs on the inside of the door.

He’s probably glad my father disappeared.

Your uncle takes a deep breath as if to make an important decision. The Cadillac on his chest stretches. Someone starts a motorbike, a woman laughs.

“What am I to do with you, boy?”

You say nothing. Uncle Runa scratches his head and sighs. You know it’s all fine now.

“Get to work. Just get to work and we won’t mention it again.”

It’s fifteen minutes later and Uncle Runa raps on the back of your head as if someone lives there, and leaves you alone. You imagine him walking down the streets, nodding at the drunks, as if they were his very special guard dogs, climbing the stairs to the second floor and your mother opening the door to him, and then they’re both laughing like the woman earlier on—high and superior—because they know you’re busy for the next few hours, while they have all the time in the world to fuck each other’s brains out. Eventually they’ll pay for it. More than six euros an hour. You’re sure of that. The justice of the world will recognize you one day. You have no idea what kind of justice that will be, you don’t really think seriously about it either, because right now you’re glad to be alone behind the counter at last.

Alone.

It’s half-price Tuesday in the cinemas, the evening screenings will be over in half an hour, and this place’ll fill up. You get ready and pull the drinks to the front of the fridge until they’re lined up neatly, you cut vegetables and mix salad. Music whispers out of the radio, you turn it up, and no one tells you to turn it down. No one wants anything from you. Apart from the customers, but that’s okay, they’re supposed to want something from you.

While your uncle generally rolls the pizza bases out in advance, you prefer to make them fresh. The customer should see that you’re doing something for him. Tomato sauce, a bit of cheese, then the topping, then a bit more cheese. You love the sound when the baking tray slides into the oven. A glance at the customer, asking if he wants anything else. Always a smile, always content. You.

Yes, me.

“Me?”

“Yes, you, what are you staring at?”

It’s two o’clock in the morning, the wave of cinemagoers ebbed away at midnight, and after that you could count the customers on one hand. You’ve stopped counting the drunks a long time ago, because they’re not real customers, they’re alkies, gabbling away at you and loading up on one last drink before they roll onto some park bench and tick off another day in their lives.

“I … I’m not staring.”

You are wondering how long you’ve been staring at her. Her green eyes gleam like distant fires, her hair is such a dark red that it’s almost black. You can’t concentrate on her mouth at the moment, because it moves and says, “Where’s the guy who makes the pizza?”

“I’m the guy who makes the pizza.”

“You’re at best twelve years old.”

You don’t react, you turn sixteen in the spring but you keep it to yourself because you’re worried that she might be older. She must be older, arrogant and loud as she is. You can’t know that she’s playing with you. She knows who you are and that you hang out with Darian, she sees you at school every day and knows you’ve noticed her too. If you’d known all that at that very moment, everything would have been a lot easier for you. As it is you’re just startled and look nervously past her. She’s alone, it’s the first time you’ve seen her alone. Normally she hangs with a group of girls who buzz around her as if she were a source of light. You particularly like the little scar on her chin, it makes her look like she is truly fragile.

She snaps her fingers around in front of your face.

“Well?”

You don’t know what she means.

“How old are you now?”

“Fifteen.”

“Never.”

You shrug and wish the moment would stay like this. Hours, make it days. You wouldn’t even have to speak. You’d make her one pizza after another, give her free drinks and look at her the whole time. Nothing more than that.

It would be nice if she would laugh and say she was sorry that she thought you were twelve, you don’t look twelve at all. That would be really nice. Only now do you notice that her eyes are glassy. She’s either stoned or drunk.

“Your name’s Mirko and you live on Seelingstrasse, right?”

“Above the falafel shop,” you say and feel as if she’s paid you a compliment. But how does she know all this? you wonder, as she says, “I’ve seen you coming out of your house a few times.”

“Ah.”

“Yes, ah.”

You look at each other, and as nothing better comes to your mind you show her your hand.

“I was in a fight today. I defended myself with a bicycle chain.”

She looks at your sore palm, looks at you, she doesn’t seem impressed. But she goes on talking to you. She says she urgently needs a phone. Her forefinger goes up in the air.

“Just one call, I swear.”

You don’t point to the phone booth behind her, you don’t ask what’s wrong with her phone. Girls always have a cell phone. Just don’t ask. Go to the back, reach into your backpack, and come back with your phone.

“Sure.”

You go to the back, reach into your rucksack, and come back with the phone. She doesn’t thank you, she takes two steps backward and taps away. You turn down the radio to hear her better.

“… no, I’m stuck here … Don’t … But I … I’ll give you ten euros, I promise. What? Please, Paul, come and fetch me … What? The what? You know what time it is? There are no buses around here. And I hate them anyway, you know that. What? Aunt Sissi can go and fuck herself.”

Suddenly she looks up, phone still to her ear, looks at you, caught you red-handed, you duck a bit but hold her gaze.

“Fuck this shit!” she says, and you are not sure if she’s talking to you.

She snaps the phone shut. You ask if there’s a problem.

“What do you know about problems?”

“I … I could take you home.”

“How are you going to take me home?”

“I can if I want.”

“But I’m not giving you ten euros.”

“That’s okay.”

You laugh, you really don’t know what you’re doing. Uncle Runa will strangle you if you shut the place for as much as a minute. But you’re making things even worse, because after Uncle Runa has strangled you he’ll cut you into pieces as soon as he finds out you’ve borrowed his old Vespa.

“On that thing?”

She has walked around the pizza stand. You pulled the tarpaulin off the bike like somebody performing a magic trick. She stands there as if she wants to buy the Vespa, then she kicks the back tire so that the bike nearly tips over. You flinch but don’t say anything. Uncle Runa drives around the block once a week to charge the battery. He got the Vespa from scrap and rebuilt it himself. He calls it Dragica.

“But I’m not wearing a helmet, just so we’re clear on that.”

She points to her piled-up hair. You nod: if she doesn’t want a helmet then she doesn’t want one. You untie the string of your apron and for a moment you smell her breath. Definitely drunk. The key to the Vespa hangs on a nail above the radio. You take it as if you do this every day. Perhaps you’ll drive along Seelingstrasse afterward and beep two times. Perhaps Uncle Runa will recognize the rattle of his Dragica and come running after you.

Once you’ve shut up shop you put on your uncle’s helmet. It’s too big, but it doesn’t matter. She stands there and holds out her hand.

“What is it?”

“Did you think I’d let you drive me?”

“But—”

“Come on, make a choice.”

You hand her the key and imagine what it’ll feel like sitting behind her. Her warmth, her presence. You’ll lean into the bends together and be like a single person. Not just you, not her—both of you. And just as you feel your excitement growing into an erection you quickly think of your mother gutting a chicken and at the same time the Vespa springs to life with a cough and bumps over the curbstone and zigzags along the street. A taxi beeps, then the lights of the Vespa come on and it disappears around the next corner.