Полная версия

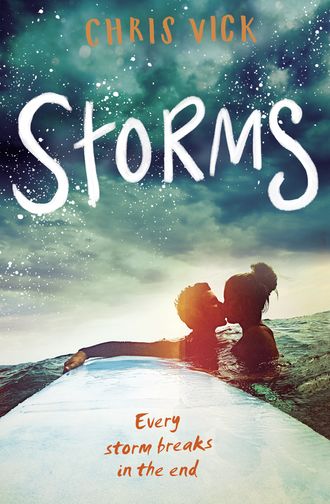

Storms

This was what a loose net could do. She imagined the whales, trapped, holding their breath till they suffocated. Struggling uselessly against the nylon nets.

Three hundred thousand whales and dolphins died this way, every year. One every two minutes.

‘Jesus Christ,’ she said. Warm tears, mixed with rain, fell down her cheeks.

She stood, useless and tiny, next to these great, dead whales.

She’d always wanted to see orcas. Now she had.

‘Fuck!’

Beano was standing fast by one of the smaller whales, barking at it, then running away, coming back, front paws and head down, pointing and barking.

‘Beano, leave it alone,’ she shouted. But the dog ignored her, growling and barking ever louder. ‘I said, leave it alone!’

She wanted some dignity for the poor things. She grabbed Beano by the scruff of the neck, and yanked him away. It was a young one, this whale, half grown, maybe a year old. Its mouth was open, its tongue lolling. It was just as dead as the others.

She put a hand on the young whale’s head, stroking the rubbery skin, and felt suddenly ashamed of being human. Of what humans do.

She looked into the whale’s eye. ‘Sorry.’

That black pupil moved. A huge, rolling marble. The eye looked at her, glinting bright and fierce. It set Hannah’s skin on fire, being looked at this way. A loud phoosh sound burst through the wind and rain as the whale breathed out of its blowhole, filling the air with a fishy stench.

Even in that mad second Hannah had a clear thought. This wasn’t like a dog or horse looking at you. It wasn’t like any animal, or human, looking at you. It was something else.

Beano was back, down on his paws, barking.

‘No, Beano. Stay,’ she shouted, letting the dog know to behave. Not to bark and run around. Not to make the whale more scared than it already was.

Then a cry came from the whale. A long, desperate whine. The eye swivelled, looking at the other whales.

‘Bloody hell,’ said Hannah, her voice trembling.

What to do now?

She stroked the whale, blown away by it, gazing at her. Like it was looking into her.

What to do?

She wanted to comfort it, to talk to it.

But that wouldn’t save its life, would it?

‘Come on, Hannah, come on. Think!’

She stood back and checked the whale over, the biologist in her getting to work. No net injuries. A female. Juvenile. It had probably followed the others in.

She reached into her coat for her phone. She’d call Jake and tell him to get help. Then she remembered: he was surfing.

‘Damn you, Jake!’ She’d phone Dad instead.

There was no service.

She’d have to start sorting this herself.

She took some pics with her phone, running around the group of whales, getting photos from all angles. Seven of them in all.

She saw two move, heard their phoosh breaths.

‘Don’t panic, stay calm,’ she said. She tried to fight the tears. They wouldn’t help the whale any more than words.

Hannah searched her mind for what she knew. For the options. The sea was just starting to go out. She could see the tideline. It’d be hours before the sea came back and covered the whales. The tide might free the live whales. But then they might stay with dead or injured family members. Or be so exhausted, so heavy and so robbed of the buoyancy of salt water that their internal organs would collapse.

If there was hope – any at all – Hannah would need people, trained MMRs: Marine Mammal Rescuers. They’d need blankets soaked in buckets of seawater to keep the skin supple. Floats, inflatables, boats. Fish? Would she need to feed them? How would they drink if they were out of the sea? Cetaceans desalinate water. How could they do that on land? There was so much she didn’t know.

Even while she was working out what to do, who to call, what she needed, a part of her was panicking.

Why this? Why now?

Right, she told herself. Get organised. Steve Hopkins, her old biology teacher. He was an MMR. He’d done seal rescues and some dolphins. She’d call him as soon as she got back.

Please don’t die, whale.

She knew people with boats. RIBs, rigid inflatables. Could they get pontoons too? All the rescues she knew about had been dolphins or seals. The young orca was bigger. But not that much bigger.

Please. Live.

Hannah stroked the whale’s head again and looked into its eye.

‘It’s okay,’ she said. ‘It’s okay.’ It wasn’t, though. Everything for the whale was as bad as it could be.

‘It’s okay.’ Hannah said it anyway. To herself. ‘It’s all right …’

Don’t say it.

‘It’s okay …’

Don’t give it a …

‘Little One.’

… name.

‘I have to go. I’ll be back, Little One. I promise.’ She leant over, above its eye, and kissed it. Then ran, calling Beano to heel.

Jake

WONDERFUL?

Fan-freaking-tastic, more like.

There was no need to duck-dive the waves. There was a conveyor-belt rip current by the cliff that took him straight out, right past the breakers. He got out back, to the side of the break point, then slowly edged into the reef, keeping a careful watch on the horizon. Waiting for sets. Getting in the sweet spot. Paddling like crazy when the right wave came.

They were big. But the power in the water was organised. It was easy surf to predict, easy to catch, the waves seeming slow at first, but walling up fast once he was on them.

Solid glass ramps to rip up.

He made huge, carving turns.

He came off each wave while it was still green, before it closed, then paddled into the rip and out again. A merry-go-round.

He could have surfed it for hours. Happily. Part of him wanted to, wanted to delay meeting Hannah, but he couldn’t stop thinking about her. After a few waves, the thoughts and doubts seeped into his mind. If Hannah went to Hawaii without him … how long before she hooked up with some geek biologist? Someone with prospects and a nice tan. They weren’t all going to be gay or ugly.

He mistimed a wave, so it went under him. Then another. His concentration was shot with all this damn thinking.

He’d done a few good waves. Time to get out. Start dealing with stuff.

He got a wave in and walked out of the water.

There was a cave to the left of the beach, tucked under the headland. A deep space filled with boulders, plastic bottles, floats, bits of net and chunks of wood.

The rubbish was always worse after a storm, but now the cave was filled with it. He could hardly see the rocks. It was ugly, but weirdly impressive. A mountain of stuff.

Something caught his eye. Among the orange plastic and old tin cans was a crate.

He remembered what Goofy had said about all sorts washing up. Gifts from the sea gods.

He put his board on a pile of seaweed, and clambered over the rocks.

There was something in the crate, no doubt about it.

He dragged it off the rocks. It was heavy.

He pulled it down to the small pebble beach.

Whatever was in the crate was covered in thick, sealed plastic. He’d need a knife to get inside it.

He didn’t have a knife. Or anything. He looked around, and found a rusted can lid. It wasn’t sharp, and his arms were surf-knackered, but he stabbed at the plastic hard, and after a few goes made a small tear.

Jabbing and yanking, he made the tear into a gash. Underneath was another layer of plastic. He cut again, curiosity driving him. He saw what was inside. Several packages of it. Something white, the size of large books, taped tight.

His mind drew a blank. There was no label, no brand. So could it be …

His heart burned with the answer, before he even thought it.

‘Drugs. Holy crap.’

He got the fear, raw and strong, like seeing a beast of a wave rising out the sea and heading his way. He looked at the path. Up at the cliff. Out to sea. There was no one there. But he felt in the open. Naked.

He cut at one of the packages. White, crystal powder burst out, coating the rusted metal then melting in the rain.

He dropped the can lid and dragged the crate up the rocks and into the depths of the cave. High up. Higher. Deeper. Beyond the tideline, where the rock was light and dry. Where the sea never reached.

He covered it in rocks and rubbish to hold it there. Then he clambered back down, picked up his board, and headed off.

What to do now?

Tell Hannah? Mum?

No, he’d tell the police. Straight away. He’d make the news.

Local surfer finds haul of drugs.

How much? What kind? What was it worth? Jake had no idea. He wasn’t into pills or powders.

Yeah, he’d tell the police, and the local papers and TV news.

Hannah would be well impressed. Plus: brilliant excuse for being late this morning.

Halfway up the cliff path he looked back into the cove. It was dead on high tide. He kept looking. Had he seen something? A broken pole, thick as a mast, poking out of the sea. Had he? The water was a mess of thrashing waves at the shore break. It was playing tricks with him. But … There.

Ten metres out was the broken mast of a boat. It was exposed when the waves sucked back. And, just below the surface, a wreck.

That was where the drugs had come from.

‘D’you know what?’ he said to himself. ‘You could always sell it, dude. Get rich.’ Maybe this was a gift from the sea gods like Goofy had talked about? Maybe it was meant to be. If he sold the drugs, he’d be able to fund Hawaii, easy.

Jake shook his head. He laughed at his own joke.

Hannah

HANNAH HAMMERED AT the front door till it opened.

‘Hannah, darling. Is everything all right?’

She threw herself at Dad, soaking his dressing gown.

‘What’s he done?’ said Dad.

‘Noth-nothing to do with Jake. There’s …’ Hannah forced the words through her sobs. ‘There’s whales. Killer whales. On the shore.’

‘What?’ Dad held her shoulders, looking into her eyes. ‘What do you mean, whales? Why are you crying? Calm down.’

‘They’re stranded. Dead mostly. But there’s a young one, alive.’ She pictured its black, marble eye. She heard its cry, like it was real. Calling to her, above the wind and rain.

‘Come and sit down. I’ll make you a cup of tea. We’ll phone the coastguard.’

Hannah pushed his hands off her. She went to the hall and called Steve Hopkins. She got his answerphone.

‘Mr Hopkins. It’s Hannah Lancaster …’ She took a deep breath, trying to calm the trembling, to put steel in her voice. ‘It’s eight fifteen. There are several stranded whales, orcas, at Whitesands beach. Some dead, at least two alive. One’s a juvenile female … I think. Call me. No … get here, please. I’ll text you some pics.’ She left her number, then used the phone again, punching the buttons with her finger. She got Jake’s voicemail too.

‘Jake. Call me!’

Why wasn’t Mr Hopkins answering? Why wasn’t Jake? Why was Dad doing nothing, apart from offering tea? It was like swimming through treacle.

‘I need him and he’s surfing,’ she sighed heavily, leaning against the wall.

‘Well,’ said Dad. ‘It’s not the first time, is it?’

Hannah didn’t bite. Now wasn’t the time.

She phoned again, punching the buttons with her finger. Got an answer message, again.

‘Call me, Jake. I need you.’

Jake

‘YOU HAVE TO be kidding me,’ said Goofy. He was sunk deep in his sofa, staring at the small jar on the table. It was a quarter full of white powder.

He stood up, went to the kitchenette and came back with a teaspoon, then opened the jar and scooped some powder on to the table.

They both leant over to examine the small mound of boulders and crystal dust.

‘I thought you might know what it is,’ said Jake.

‘Oh, really. Why’s that, then?’

‘I thought you might have … I dunno. I just did. Could you could test it?’

In films, people licked a finger and tasted a dab. Goofy just stared at the powder.

‘I come down ’ere to get away from that kind of shit. I don’t care what it is.’

‘I thought you came here to surf?’

‘Mostly.’

Jake thought of all the things Goofy had said about his past. And not said. Maybe Goofy had run from something as much as to something.

‘Any idea?’ said Jake.

‘Coke at a guess. MDMA, maybe. Smack, possibly. Why’d you want to know?’

‘So I know what to do with it.’

‘You don’t do anything with it. You tell the law. I hate the bastards, but they have their uses. You don’t want some kids finding it, do you?’

‘Any idea how much it’s worth?’ said Jake.

‘If it’s coke, there’s more than a few grams there. A grand? Two, three, maybe.’

Jake sat bolt upright. He thought of the full jam jar under his bed and the crate hidden on the beach. How much money was in there?

‘A thousand quid, plus? For that tiny amount,’ he said.

‘Yeah. For that tiny amount,’ said Goofy. ‘Why, how big is the package it came from?’

‘Big,’ Jake said. The air in the room was suddenly thick, the roaring wind a million miles away.

Goofy stared at him, his eyebrows knotted. ‘You don’t want to worry about this, Jakey. You’re getting on a plane soon.’

‘And how am I going to afford that?’ Jake shrugged, and nodded. Suggesting something. It took Goofy a few seconds to twig what that something was.

‘Oh no,’ said Goofy. ‘No, no, no, no, no. You are kidding.’

‘Imagine it, Goofy,’ said Jake in a forced whisper. ‘All that dosh. Thousands. More.’

Goofy stood up, keeping an eye on the small hill of powder, as if it was a coiled snake waiting to spring up and bite him. ‘This ain’t a bit of weed, Jake. This is ten years in prison. More, depending on … How much is there?’

Jake didn’t want to freak Goofy out. Not more than he already was. Better not tell the whole truth. ‘The package is about the size of a bag of flour. Is that a lot?’

‘No, Jake. This …’ Goofy pointed at the table, ‘is a lot. That’s a small mountain. You’re talking about the entire Himalayas. Tens of thousands, like. More possibly.’

‘Enough to get us made. For life.’

Goofy started pacing the flat, rubbing his hands together, his voice getting louder. ‘Enough to get you banged up with rapists and murderers till your hair’s gone grey!’ He marched to the door, and opened it, letting in a blast of wind and rain. He looked around, then came back in.

‘Did you see anyone down there? Did anyone see you?’

‘No … Hold on … one guy. Yeah, this surfer. He’d been down before me. Older bloke with a craggy face.’

‘Anyone else?’

‘No, why?’

Goofy didn’t appear to hear the question. He walked to the table, picked up the jar, put it just below the level of the table and brushed the powder back in with his finger. He put his hand to his mouth, as if to lick off the white stain. He paused, then licked it anyway. He looked at the ceiling, thinking. Then nodded.

‘That’s high-grade cocaine, Jake.’ He went quickly to the sink and poured the powder in. He put the tap on full, then rinsed the jar out.

‘What you doing?’ said Jake, standing. ‘That’s more than a thousand quid!’

‘Bollocks. I’ve seen what this poison does to fellows. Girls too. It’s not happening to you, brother. Coke is evil shit, Jake.’

He turned and held the clean jam jar out to Jake, beaming.

‘What the hell? Look at us, Goofy.’ Jake stood up and pointed at his mate, then at himself.

‘What d’you mean?’

‘Where we headed? What kind of future we got?’

Goofy looked down at his stained jeans, at the rented bedsit with its damp walls and fag-burned carpet.

‘Where we going, eh?’ said Jake.

‘We do okay.’

‘Now. Plenty of surfs, beers, laughs. But in a year. Five?’

Goofy just shrugged.

‘I need to get on that plane,’ said Jake.

‘Hawaii’s not that important.’

‘It is. Hannah is. This is a chance, Goof. A gift from the sea gods, like you said. I’ll get rid of a load of it cheap. Just enough for a ticket, maybe a bit of spends. To set me up. I’ve got it figured out. I want to be a board shaper.’

‘So does every surfer. You have to be good, to get experience.’

‘I am good. I’m good with boats and wood; I’ve shaped a bit with Ned. I know surfing as well as anyone.’ He could convince Goofy. If he’d just listen! ‘I get there, right? I work, for free, with Alan Seymour Boards. Learn the craft. I come back with a rack of boards shaped in Hawaii. Who else round here can offer that?’

‘All right. It’s a good plan. If anyone can pull it off, you can. But you ain’t funding it like this. Not if I can help it.’

‘You won’t help me?’

Goofy folded his arms. He stood, biting his lip. ‘I can’t get involved in anything like that.’

‘Come on, Goofy. I helped you when you needed it.’

Goofy looked at Jake sharply. Jake was reminding Goofy of when he had arrived in Cornwall. A crusty loser, with a surfboard. Who’d needed clothes, food, a place to stay. Time to call in that favour. It was a rotten thing to do, but he was desperate.

‘You helped me get out of shit,’ said Goofy. ‘Not into it. I can’t help. Look, go see yer man Ned. He might help you. He sells a bit more than boards.’

‘Yeah, weed. He’s known for it.’

‘More than weed I heard.’

‘Ned? I never knew.’

‘Well, he doesn’t advertise, does he? Any case, he might know someone. Or someone who knows someone. Good luck.’

‘Thanks, Goofy.’ He opened his arms wide for a bear hug. Jake’s way of saying: We still okay? Goofy hugged him, then held him at arm’s length, keeping a tight grip on his shoulders.

‘I’m telling you about Ned for one reason, so you don’t start trotting into pubs asking random folk if they want to buy drugs. You’d only end up arrested, beat up or ripped off. Possibly all them things. You still might. And be careful. Ned ain’t exactly sensible. Open his head, and there’s no brain, just dozens of tiny monkeys, dancing. I don’t think he knows what year it is most of the time, he’s smoked that much. Now get out of here. Go see that bird of yours. Seeing ’er might put sense in your thick head.’

Goofy slapped Jake on the back as he went out of the door.

The door closed behind Jake with a cold thud.

He was alone. He’d wanted Goofy by his side. No one would mess with him, then. You could rely on Goofy.

Ned was a different story.

Hannah

THE CLOCK ON the kitchen wall told her it was an hour since she’d made those calls. And so far, nothing. She paced up and down the kitchen, biting her nails.

‘Hannah!’ said Dad. ‘Darling. Why don’t you sit down? Take your coat off.’

Mum and Dad were sitting at the table. At one end, Mum had laid breakfast: china cups, a rack of toast, a bowl of freshly boiled eggs. At the other end, Hannah had piled up blankets, a bucket, a camera and a notebook. Beano sat at the door, watching her, unsure if he should go and lie in his basket, or if they were off for another walk.

‘Hannah, sit down,’ said Dad.

‘The whales …’

‘The whales will wait till this marine-rescue chap calls, or arrives. There’s nothing you can do yourself, is there? It’s best to wait here.’

She hated Dad being right. She hated his self-confident, knowing-he-is-right-ness. Hannah wanted nothing more than to pelt down to the beach. To see Little One. To try to comfort the young whale. That much, at least.

‘Hannah, please eat something,’ said Mum.

‘I’m not hungry,’ she snapped. Then quickly added: ‘Sorry.’

‘Okay, darling. I’ll make up a packed lunch.’

‘Thanks.’

‘You pamper that girl,’ said Dad.

The phone rang in the hall. It hadn’t rung three times before Hannah answered.

‘Hannah Lancaster? This is Steve.’ She could barely make out his voice through the crackle and shrieking wind. She put a finger in her other ear.

‘Our people are down here now,’ he said. ‘Sorry I didn’t call earlier. I’ve come off the beach to get a signal.’

‘Oh. Right. Great. I’m coming down.’

‘You haven’t told anyone about this, have you?’

‘No. Why?’

‘We don’t want crowds – they get in the way. We need to keep the media away too, as long as possible.’

‘I’m coming down. I can help,’ she said.

‘We have all the help we need. But if you want to come and watch …’ Steve’s voice drowned in white noise. ‘You’re breaking up …’

‘How are the whales?’ The line was dead.

‘Is everything okay?’ said Dad. He was right beside her. So was Mum.

Hannah dodged past them, grabbed the bucket, shoved the blankets and notebook and camera inside it, and left.

‘Wait,’ Dad shouted through the open door, holding Beano by the collar. ‘I’ll get my coat.’

Hannah

HANNAH STOPPED RUNNING and stood on the sand, watching.

The whales were the same. Limp, giant statues. The sea had retreated to mid-tide, as though it had dumped the whales and run off, leaving them to die.

The rain had stopped. Two girls in hi-vis orange jackets stood inside a fence of yellow netting that had been erected round the whales. Outside the cordon, a small crowd watched as rescuers in waterproofs poured buckets of seawater on to blankets and towels that had been laid over the whales’ bodies.

Hannah counted. Three with towels and blankets draped over them, and four without. That meant three alive, four dead.

Little One was one of the three. Hannah’s heart sang. She ran to the cordon and dropped her bucket, ready to climb over, to go and see the young whale. But a young woman stepped in front of her.

‘Sorry, Miss. Marine-rescue team only.’

‘I’ve done training, I’m not qualified yet, but … is Steve here?’

The girl pointed. Steve stood behind the whales talking into a brick of a radio phone. Hannah waved. He gave her a quick smile. Hannah looked at Little One. The whale’s head moved, slightly, its eye rolling around, and – she was certain – seeing her. Its tail lifted and dropped. The whale moaned. A low cry of despair that reached inside Hannah and tore at her heart.

She stepped towards the fence, ready to climb over.

‘Hannah,’ said Steve, walking over.

‘What’s going to happen?’ she said.

‘We don’t know yet,’ said Steve. His face was pale, his forehead creased with stress.

‘Can I come in? I want to see the young one. When I found them I knew they weren’t all dead, because she cried out to me.’

‘You understand how this works, right? How serious this is.’

She did. She understood too well.

An older, serious-looking man was examining the whales. He had a stethoscope and a large oilskin case. He was a vet at a stranding, there to sort the living from the dead, the healthy from the sick, the ones that had hope from the ones that didn’t. Inside the bag would be vials, some full of vitamins and minerals, others loaded with poison ready to be injected.

Hannah swallowed hard. She wanted to be a marine biologist. She’d see plenty of dead, and dying, whales in years to come. She had to get used to it.

Steve got close, so no one would overhear. In the low tone of a doctor delivering bad news he said, ‘That animal is not in good shape. Even if we refloat it, it won’t leave its mother, who is dead. And if it did, it wouldn’t survive out there,’ he pointed at the raging sea.