Полная версия

Roverandom

The most intriguing connection between Roverandom and the mythology, however, occurs when the ‘oldest whale’, Uin, shows Roverandom ‘the great Bay of Fairyland (as we call it) beyond the Magic Isles’, and further off ‘in the last West the Mountains of Elvenhome and the light of Faery upon the waves’ and ‘the city of the Elves on the green hill beneath the Mountains’ (see here). For this is precisely the geography of the West of the world in the ‘Silmarillion’, as that work existed in the 1920s and 1930s. The ‘Mountains of Elvenhome’ are the Mountains of Valinor in Aman, and the ‘city of the Elves’ is Tún – to use the name given it both at one time in the mythology and in the first text (only) of Roverandom. Uin too is drawn from The Book of Lost Tales, and although he is not here quite his namesake ‘the mightiest and most ancient of whales’ (Part One, p.118), still he is able to carry Roverandom to within sight of the Western lands, which by this time in the development of the legendarium were hidden from mortal eyes behind darkness and perilous waters.

Uin says that he would ‘catch it’ if it was found out (presumably by the Valar, or Gods, who live in Valinor) that he had shown Aman to someone (even a dog!) from the ‘Outer Lands’ – that is, from Middle-earth, the world of mortals. In Roverandom that world in some ways is meant to be our own, with many real places mentioned by name. Roverandom himself ‘after all was an English dog’ (see here). But in other ways it is clearly not our earth: for one thing, it has edges over which waterfalls drop ‘straight into space’ (see here). This is not quite the earth depicted in the legendarium either, although it too is flat; but the moon of Roverandom, exactly like the one in The Book of Lost Tales, moves beneath the world when it is not in the sky above.

As more of Tolkien’s works have been published in the quarter-century since his death, it has become clear that nearly all of his writings are interrelated, if only in small ways, and that each sheds a welcome light upon the others. Roverandom illustrates once again how the legendarium that was Tolkien’s life-work influenced his storytelling, and it looks forward (or laterally) to writings on which Roverandom itself may have been an influence – especially to The Hobbit, whose composition (beginning possibly in 1927) was contemporaneous with the writing down and revision of Roverandom. Few readers of The Hobbit indeed will fail to notice (inter alia) similarities between Rover’s fearsome flight with Mew to his cliffside home and Bilbo’s to the eagles’ eyrie, and between the spiders Roverandom encounters on the moon and those of Mirkwood; that both the Great White Dragon and Smaug the dragon of Erebor have tender underbellies; and that the three crusty wizards in Roverandom – Artaxerxes, Psamathos, and the Man-in-the-Moon – each in his own way is a precursor of Gandalf.

* * *

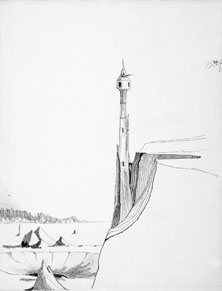

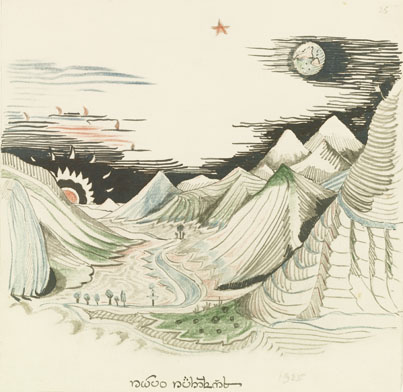

Before proceeding to the text it remains only to say a few additional words about the pictures accompanying it. They were not planned as illustrations for a printed book, and are not, in their subject matter, spaced equally throughout the story. Nor are they consistent even in style or media: two are in pen and ink, two in watercolour, and one chiefly in coloured pencil. Four are fully developed, the watercolours especially, while the fifth, the view of Rover arriving on the moon, is a much lesser work, with Rover, Mew, and the Man-in-the-Moon uncomfortably small.

In this drawing Tolkien was perhaps more interested in the tower and the (accurate) barren landscape, which however gives no hint of the lunar forests described in Roverandom.

The earlier Lunar Landscape is more faithful to the text: it includes trees with blue leaves, and ‘wide open spaces of pale blue and green where the tall pointed mountains threw their long shadows far across the floor’ (see here). It presumably depicts the moment when Roverandom and the Man-in-the-Moon, returning from their visit to the dark side, see ‘the world rise, a pale green and gold moon, huge and round above the shoulders of the Lunar Mountains’ (see here). But here the world is clearly not flat: only the Americas are shown, and therefore England and the other earthly locations mentioned in the tale must be on the opposite side of a globe. The title Lunar Landscape is written on the work in an early form of Tolkien’s Elvish script tengwar.

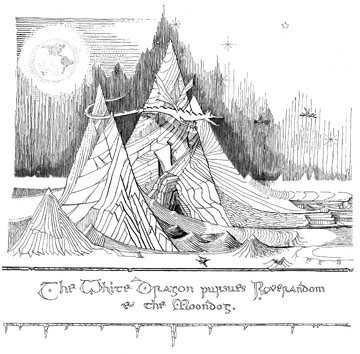

The White Dragon Pursues Roverandom & the Moondog is also faithful to the text, and has several points of interest besides the dragon and the two winged dogs. Above the titling are one of the moon-spiders and, probably, a dragonmoth; and in the sky again the earth is shown as a globe. When he came to illustrate The Hobbit Tolkien used the same dragon on his map Wilderland, and the same spider in his drawing of Mirkwood. ‘Moondog’ as in the title was used (variably with ‘moon-dog’) only in the earliest texts.

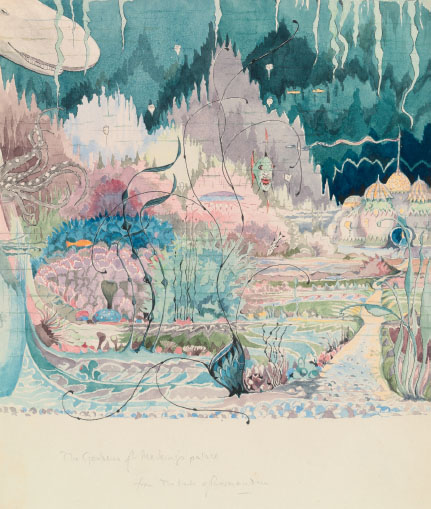

The splendid watercolour The Gardens of the Merking’s Palace reveals the structure of ‘pink and white stone’ as if it were an aquarium decoration, perhaps with a hint of the Royal Pavilion at Brighton. Tolkien chose to show the palace and its gardens in all their beauty, rather than Roverandom making his fearful way up the path; probably we are meant to be seeing through his eyes. The whale Uin is in the upper left corner, much like the leviathan in one of Rudyard Kipling’s illustrations for ‘How the Whale Got His Throat’ in his Just So Stories (1902). ‘Merking’ as in the title appeared only in the earliest texts, variably with ‘mer-king’ (the sole form in the final typescript). Tolkien was also inconsistent in his spelling of other mer-compounds, which in the present text we have regularized as hyphenated, excepting the familiar spellings mermaid (mermaids, mermaidens) and mermen.

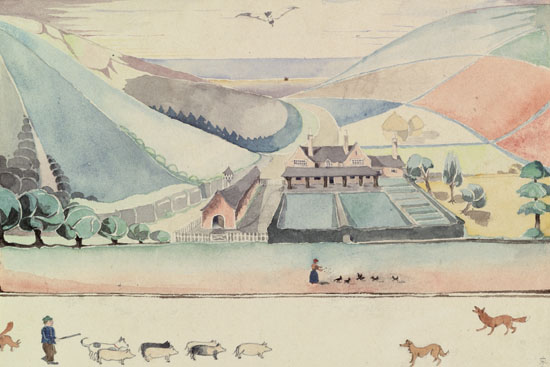

The picture House Where ‘Rover’ Began His Adventures as a ‘Toy’, no less accomplished a watercolour, is however a puzzle. Its title would suggest that it depicts the house where Rover first met Artaxerxes, though no indication is given in the text that this was on or near a farm. Also the glimpse of the sea in the background and the gull flying overhead would contradict the statement in the text that Rover ‘had never either seen or smelt the sea’ before he was taken to the beach by little boy Two, ‘and the country village where he had been born was miles and miles from sound or snuff of it’ (see here). Nor can this be the little boys’ father’s house, which is described as being white and on a cliff with gardens running down to the sea. We are almost tempted to wonder if this picture was originally unconnected with the story, and then details, such as the gull, were added while it was being painted to give it relevance. The black and white dog at bottom left may be intended as a picture of Rover, and the black animal in front of him – like Rover, partially obscured by a pig – may be the cat, Tinker; but none of this is certain.

The text that follows is based on the latest version of Roverandom. Tolkien never fully edited the work for publication, and it cannot be doubted that he would have made a great many revisions and corrections, to make it more suitable for an audience apart from his immediate family, had it been accepted by Allen & Unwin as a successor to The Hobbit. In the event it was left with a number of errors and inconsistencies. When writing at speed Tolkien tended to be inconsistent in his manner of punctuation and capitalization; for Roverandom we have followed his (generally minimalist) practice where his intentions are clear, but have regularized punctuation marks and capitalization where it seemed necessary, and have corrected a few obvious typographical errors. With Christopher Tolkien’s consent we have also amended a very small number of awkward phrases (retaining others); but for the most part the text is as its author left it.

For their advice and guidance in the making of this book we are especially grateful to Christopher Tolkien, whom we also thank for supplying the statement in his father’s diary quoted on (see here); and to John Tolkien, who shared with us his memories of Filey in 1925. We would also like to acknowledge the assistance and encouragement of Priscilla and Joanna Tolkien; Douglas Anderson; David Doughan; Charles Elston; Michael Everson; Verlyn Flieger; Charles Fuqua; Christopher Gilson; Carl Hostetter; Alexei Kondratiev; John Rateliff; Arden Smith; Rayner Unwin; Patrick Wynne; David Brawn and Ali Bailey of HarperCollins; Judith Priestman and Colin Harris of the Bodleian Library, Oxford; and the staff of the Williams College Library, Williamstown, Massachusetts.

Christina Scull

Wayne G. Hammond

1

ONCE UPON A TIME there was a little dog, and his name was Rover. He was very small, and very young, or he would have known better; and he was very happy playing in the garden in the sunshine with a yellow ball, or he would never have done what he did.

Not every old man with ragged trousers is a bad old man: some are bone-and-bottle men, and have little dogs of their own; and some are gardeners; and a few, a very few, are wizards prowling round on a holiday looking for something to do. This one was a wizard, the one that now walked into the story. He came wandering up the garden-path in a ragged old coat, with an old pipe in his mouth, and an old green hat on his head. If Rover had not been so busy barking at the ball, he might have noticed the blue feather stuck in the back of the green hat, and then he would have suspected that the man was a wizard, as any other sensible little dog would; but he never saw the feather at all.

When the old man stooped down and picked up the ball – he was thinking of turning it into an orange, or even a bone or a piece of meat for Rover – Rover growled, and said:

‘Put it down!’ Without ever a ‘please’.

Of course the wizard, being a wizard, understood perfectly, and he answered back again:

‘Be quiet, silly!’ Without ever a ‘please’.

Then he put the ball in his pocket, just to tease the dog, and turned away. I am sorry to say that Rover immediately bit his trousers, and tore out quite a piece. Perhaps he also tore out a piece of the wizard. Anyway the old man suddenly turned round very angry and shouted:

‘Idiot! Go and be a toy!’

After that the most peculiar things began to happen. Rover was only a little dog to begin with, but he suddenly felt very much smaller. The grass seemed to grow monstrously tall and wave far above his head; and a long way away through the grass, like the sun rising through the trees of a forest, he could see the huge yellow ball, where the wizard had thrown it down again. He heard the gate click as the old man went out, but he could not see him. He tried to bark, but only a little tiny noise came out, too small for ordinary people to hear; and I don’t suppose even a dog would have noticed it.

So small had he become that I am sure, if a cat had come along just then, she would have thought Rover was a mouse, and would have eaten him. Tinker would. Tinker was the large black cat that lived in the same house.

At the very thought of Tinker, Rover began to feel thoroughly frightened; but cats were soon put right out of his mind. The garden about him suddenly vanished, and Rover felt himself whisked off, he didn’t know where. When the rush was over, he found he was in the dark, lying against a lot of hard things; and there he lay, in a stuffy box by the feel of it, very uncomfortably for a long while. He had nothing to eat or drink; but worst of all, he found he could not move. At first he thought this was because he was packed so tight, but afterwards he discovered that in the daytime he could only move very little, and with a great effort, and then only when no one was looking. Only after midnight could he walk and wag his tail, and a bit stiffly at that. He had become a toy. And because he had not said ‘please’ to the wizard, now all day long he had to sit up and beg. He was fixed like that.

After what seemed a very long, dark time he tried once more to bark loud enough to make people hear. Then he tried to bite the other things in the box with him, stupid little toy animals, really only made of wood or lead, not enchanted real dogs like Rover. But it was no good; he could not bark or bite.

Suddenly someone came and took off the lid of the box, and let in the light.

‘We had better put a few of these animals in the window this morning, Harry,’ said a voice, and a hand came into the box. ‘Where did this one come from?’ said the voice, as the hand took hold of Rover. ‘I don’t remember seeing this one before. It’s no business in the threepenny box, I’m sure. Did you ever see anything so real-looking? Look at its fur and its eyes!’

‘Mark him sixpence,’ said Harry, ‘and put him in the front of the window!’

There in the front of the window in the hot sun poor little Rover had to sit all the morning, and all the afternoon, till nearly tea-time; and all the while he had to sit up and pretend to beg, though really in his inside he was very angry indeed.

‘I’ll run away from the very first people that buy me,’ he said to the other toys. ‘I’m real. I’m not a toy, and I won’t be a toy! But I wish someone would come and buy me quick. I hate this shop, and I can’t move all stuck up in the window like this.’

‘What do you want to move for?’ said the other toys. ‘We don’t. It’s more comfortable standing still thinking of nothing. The more you rest, the longer you live. So just shut up! We can’t sleep while you’re talking, and there are hard times in rough nurseries in front of some of us.’

They would not say any more, so poor Rover had no one at all to talk to, and he was very miserable, and very sorry he had bitten the wizard’s trousers.

I could not say whether it was the wizard or not who sent the mother to take the little dog away from the shop. Anyway, just when Rover was feeling his miserablest, into the shop she walked with a shopping-basket. She had seen Rover through the window, and thought what a nice little dog he would be for her boy. She had three boys, and one was particularly fond of little dogs, especially of little black and white dogs. So she bought Rover, and he was screwed up in paper and put in her basket among the things she had been buying for tea.

Rover soon managed to wriggle his head out of the paper. He smelt cake. But he found he could not get at it; and right down there among the paper bags he growled a little toy growl. Only the shrimps heard him, and they asked him what was the matter. He told them all about it, and expected them to be very sorry for him, but they only said:

‘How would you like to be boiled? Have you ever been boiled?’

‘No! I have never been boiled, as far as I remember,’ said Rover, ‘though I have sometimes been bathed, and that is not particularly nice. But I expect boiling isn’t half as bad as being bewitched.’

‘Then you have certainly never been boiled,’ they answered. ‘You know nothing about it. It’s the very worst thing that could happen to anyone – we are still red with rage at the very idea.’

Rover did not like the shrimps, so he said: ‘Never mind, they will soon eat you up, and I shall sit and watch them!’

After that the shrimps had no more to say to him, and he was left to lie and wonder what sort of people had bought him.

He soon found out. He was carried to a house, and the basket was set down on a table, and all the parcels were taken out. The shrimps were taken off to the larder, but Rover was given straight away to the little boy he had been bought for, who took him into the nursery and talked to him.

Rover would have liked the little boy, if he had not been too angry to listen to what he was saying to him. The little boy barked at him in the best dog-language he could manage (he was rather good at it), but Rover never tried to answer. All the time he was thinking he had said he would run away from the first people that bought him, and he was wondering how he could do it; and all the time he had to sit up and pretend to beg, while the little boy patted him and pushed him about, over the table and along the floor.

At last night came, and the little boy went to bed; and Rover was put on a chair by the bedside, still begging until it was quite dark. The blind was down; but outside the moon rose up out of the sea, and laid the silver path across the waters that is the way to places at the edge of the world and beyond, for those that can walk on it. The father and mother and the three little boys lived close by the sea in a white house that looked right out over the waves to nowhere.

When the little boys were asleep, Rover stretched his tired, stiff legs and gave a little bark that nobody heard except an old wicked spider up a corner. Then he jumped from the chair to the bed, and from the bed he tumbled off onto the carpet; and then he ran away out of the room and down the stairs and all over the house.

Although he was very pleased to be able to move again, and having once been real and properly alive he could jump and run a good deal better than most toys at night, he found it very difficult and dangerous getting about. He was now so small that going downstairs was almost like jumping off walls; and getting upstairs again was very tiring and awkward indeed. And it was all no use. He found all the doors shut and locked, of course; and there was not a crack or a hole by which he could creep out. So poor Rover could not run away that night, and morning found a very tired little dog sitting up and pretending to beg on the chair, just where he had been left.

The two older boys used to get up, when it was fine, and run along the sands before their breakfast. That morning when they woke and pulled up the blind, they saw the sun jumping out of the sea, all fiery-red with clouds about his head, as if he had had a cold bathe and was drying himself with towels. They were soon up and dressed; and off they went down the cliff and onto the shore for a walk – and Rover went with them.

Just as little boy Two (to whom Rover belonged) was leaving the bedroom, he saw Rover sitting on the chest-of-drawers where he had put him while he was dressing. ‘He is begging to go out!’ he said, and put him in his trouser-pocket.

But Rover was not begging to go out, and certainly not in a trouser-pocket. He wanted to rest and get ready for the night again; for he thought that this time he might find a way out and escape, and wander away and away, until he came back to his home and his garden and his yellow ball on the lawn. He had a sort of idea that if once he could get back to the lawn, it might come all right: the enchantment might break, or he might wake up and find it had all been a dream. So, as the little boys scrambled down the cliff-path and galloped along the sands, he tried to bark and struggle and wriggle in the pocket. Try how he would, he could only move a very little, even though he was hidden and no one could see him. Still he did what he could, and luck helped him. There was a handkerchief in the pocket, all crumpled and bundled up, so that Rover was not very deep down, and what with his efforts and the galloping of his master, before long he had managed to poke out his nose and have a sniff round.

Very surprised he was, too, at what he smelt and what he saw. He had never either seen or smelt the sea before, and the country village where he had been born was miles and miles from sound or snuff of it.

Suddenly, as he was leaning out, a great big bird, all white and grey, went sweeping by just over the heads of the boys, making a noise like a great cat on wings. Rover was so startled that he fell right out of the pocket onto the soft sand, and no one heard him. The great bird flew on and away, never noticing his tiny barks, and the little boys walked on and on along the sands, and never thought about him at all.

At first Rover was very pleased with himself.

‘I’ve run away! I’ve run away!’ he barked, toy barking that only other toys could have heard, and there were none to listen. Then he rolled over and lay in the clean dry sand that was still cool from lying out all night under the stars.

But when the little boys went by on their way home, and never noticed him, and he was left all alone on the empty shore, he was not quite so pleased. The shore was deserted except by the gulls. Beside the marks of their claws on the sand the only other footprints to be seen were the tracks of the little boys’ feet. That morning they had gone for their walk on a very lonely part of the beach that they seldom visited. Indeed it was not often that anyone went there; for though the sand was clean and yellow, and the shingle white, and the sea blue with silver foam in a little cove under the grey cliffs, there was a queer feeling there, except just at early morning when the sun was new. People said that strange things came there, sometimes even in the afternoon; and by the evening the place was full of mermen and mermaidens, not to speak of the smaller sea-goblins that rode their small sea-horses with bridles of green weed right up to the cliffs and left them lying in the foam at the edge of the water.

Now the reason of all this queerness was simple: the oldest of all the sand-sorcerers lived in that cove, Psamathists as the sea-people call them in their splashing language. Psamathos Psamathides was this one’s name, or so he said, and a great fuss he made about the proper pronunciation. But he was a wise old thing, and all sorts of strange folk came to see him; for he was an excellent magician, and very kindly (to the right people) into the bargain, if a bit crusty on the surface. The mer-folk used to laugh over his jokes for weeks after one of his midnight parties. But it was not easy to find him in the daytime. He liked to lie buried in the warm sand when the sun was shining, so that not more than the tip of one of his long ears stuck out; and even if both of his ears were showing, most people like you and me would have taken them for bits of stick.

It is possible that old Psamathos knew all about Rover. He certainly knew the old wizard who had enchanted him; for magicians and wizards are few and far between, and they know one another very well, and keep an eye on one another’s doings too, not always being the best of friends in private life. At any rate there was Rover lying in the soft sand and beginning to feel very lonely and rather queer, and there was Psamathos, though Rover did not see him, peeping at him out of a pile of sand that the mermaids had made for him the night before.

But the sand-sorcerer said nothing. And Rover said nothing. And breakfast-time went by, and the sun got high and hot. Rover looked at the sea, which sounded cool, and then he got a horrible fright. At first he thought that the sand must have got into his eyes, but soon he saw that there could be no mistake: the sea was moving nearer and nearer, and swallowing up more and more sand; and the waves were getting bigger and bigger and more foamy all the time.

The tide was coming in, and Rover was lying just below the high-water mark, but he did not know anything about that. He grew more and more terrified as he watched, and thought of the splashing waves coming right up to the cliffs and washing him away into the foaming sea (far worse than any soapy bathing-tub), still miserably begging.