Полная версия

Plume

Add to that what you gather yourself. People have no idea how much they say in the course of a normal conversation. Talk to someone for an hour and the transcript can approach 5,000 words. Trim away all the worthless ‘yeahs’ and ‘umms’ and ‘I thinks’, cut all the bits where they’re ordering a drink or asking their PR how much time they have left, and unless they are the worst kind of drone celeb you will still have far more quotable material than can be squeezed into the 2–3,000 words you have been given to write.

So you select. You edit. And here the interview stops being photography and becomes impressionist painting. Ten quotes that make the subject look generous, warm and inspiring can be found in the transcript. The same transcript can yield ten quotes that make them sound weary, bitter and self-centred. The person remains the same, what they said remains the same, but they are seen through a series of funhouse mirrors, appearing first hypertrophied, then stunted, then undulating …

A correction. What they said does not remain the same, not quite. The interviewer does not merely prune, then select. They edit. People talk nonsense. They speak in fragments and non-sequiturs, they repeat themselves and omit. Sometimes they skip verbs, sometimes nouns. And by ‘they’ I mean we. We are all, always, skirting total aphasia, total nonsense. But we don’t mind, we don’t even hear it, because our inner editors smooth it all away in the hearing. The real evolutionary breakthrough was not the ability to speak – it was the ability to understand.

Record the unedited spew that is natural human speech and write it down word for word, and the result is unprintable. The subject would be furious if you put these words – their exact words – in their mouth. Rightly so. They’d sound like a babbling fool. The work needed to correct this impression – to make people sound as they believe they sound – isn’t slight. It goes far beyond cutting out the ‘umms’ and ‘ahhs’. It can entail wholesale reorganisation and rephrasing of what was said. In other words – in other words! – the writer must extract the ore of what was meant from the slag of what was spoken. Done correctly, the subject won’t believe a word has been changed.

Even after explaining these difficulties, admitting the fundamental elasticity of the truth, the professional profile journalist will still insist that truth is the very soul of their work. Their profile, they will claim, is a fair portrayal, or an authentic depiction of an encounter. But I was beginning to believe that a true portrayal of another person might not be possible – not because the truth was impossible to portray, but because there might not be any truth to expose. It might be that every man and woman is a fractal Janus, infinitely involuted, showing at least two faces at every level of magnification. It might be that every human encounter is a cryptogram impervious to codebreakers.

The data Polly had collected gave the impression of idleness. If she was in a position to fill in the widening gaps in my day, that impression would only grow stronger. Perhaps she had already guessed the truth. I have considered telling the truth. I have wondered what that would sound like, what I would say, and where I would begin. But even a straightforward statement of facts is not the truth, not the whole truth.

I am not idle. I work hard. I start early, I work through lunch, I work in the evening, I work late into the night. I work until I drop. When I am kept away from work, by the Monday morning meeting or by the quiet drink I enjoyed with Mohit that same evening, work was always on my mind.

Idle, no. Polly would not see, but it is there to see, out on the streets. You are outside a pub, queueing for a cashpoint, waiting for a bus. They approach and ask for money. Maybe they have a story they tell. Look at them – the stance, the gait, the eyes. Abject, yes. But not idle. No languor, no sloth. They are busy. They are on a deadline. They are working. Addiction is work, all-consuming, urgent work. And unlike my post at the magazine, the job security is total. Addiction will never fire me. It will never let me go.

It was true that I was often late for work. But I overslept less than you might expect – I was rarely given the chance, rising promptly, at 7 a.m., when the drilling started. Next door was renovating their house. Renovate: to make new again. They were stripping that word back to its roots just as they were rebuilding their house down to its foundations. Deep into the London clay they dug, scraping out precious extra inches of floor area and headroom. They were in my head-room too. Their busy pneumatic drills were working perhaps only feet – perhaps only inches – from where my head rested on an under-washed pillowcase. They might as well have been drilling inside my skull.

I no longer got hangovers. I was never sober enough. So perhaps the universe supplied the drilling as a substitute. All the oxygen was gone from the room already. There was air, but it could not nourish or sustain. And it was thick with dust, created and stirred up by the building work. Dark grey was encroaching in the corners of the window panes, smooth surfaces crackled beneath my fingertips. My nose was blocked.

Shower first, then breakfast, I thought. But the Need disagreed. You’ll have time for that later, it lied. Me first. Still wearing no more than the T-shirt and boxers I had slept in, I went to the fridge, took out a can of Stella, cracked it, and took a swig.

The grit and stain was washed from the recesses of my mouth. Cold brilliance. Appeased for the moment, the Need receded. The choking fog around me parted and I saw the leftovers from the previous night. Grey tatters of lettuce on a sauce-smeared, greasy plate, plain newspapers balled up nearby, seven empties crowded on the little table beside the sofa – none spilled. The cushions were piled up on one side of the sofa, still indented with the impression made by my reclining form. It was dark in the living room, but it was always dark in the living room. The only natural light came through the glass roof of the kitchen extension, and that was the depleted stuff that had found its way through the winter sky and down into a canyon between the backs of Victorian terraced houses. It was further filtered by the grime that had built up on the glass roof, and the branches of the neighbours’ lime tree.

‘Good morning,’ I said to the black skeleton of the tree. It dripped filth in response.

I started to pick up empties. One turned out to be two-thirds full, and the surprise weight almost caused it to slip from my unready fingers. Another, tucked behind the lamp on the table, had about a third left in it. How long had they been there? Were they from last night, or earlier? Three days was a gamble.

The empty empties I crushed and put in the recycling; the part-empties I left by the sink. Then I sat on the sofa. The drilling had not stopped, or even subsided, but I had a little insulation in my head now, and it was at the other end of the flat. And only on the one side, for now. I felt pretty good, relatively. The meeting with Pierce was set for eleven, a civilised time, and I wasn’t expected in the office until Thursday. That was an aeon away. All that mattered was not screwing up the Pierce interview – and I was unusually well-prepared. I had actually read Pierce’s books and many of his articles; that was the reason I wanted to interview him in the first place. I just had to focus and stick to it for a couple of days, and the Polly-threat might recede, give me some time and space to get my head together, to make some changes, stabilise things.

‘Getting myself back on track, yes indeed,’ I said to the tree. ‘What do you have to say about that? Two interviews today, and they’re both going to go great.’

It had nothing to say about that.

The TV and DVD player were on standby, not completely off; they had done this themselves during the night. So discreet, so obliging. I turned the TV on and switched to the news. London Blaze, said the red caption beside the crawl.

‘… real concern isn’t the fuel but some of the additives used in some of these related processes, which we understand were on the site.’ Not a newsreader voice but the unpolished, hesitant voice of an expert, speaking over pre-dawn helicopter footage of the fire, hungry orange squirts of flame, the smoke column like a thick black neck attached to a head that was buried in the ground, swallowing, chewing, consuming. Around it, a necklace of twinkling blue lights.

‘So just how concerned should we be?’ The interviewer, a female voice, cut in. I liked this question. I wanted to precisely calibrate my concern.

‘Well, as I say,’ the interviewee, a male voice, said, ‘it’s not really a question of the fuel but the other chemicals that may have been present; now we don’t know what these were exactly, not as yet, but we understand there were substantial quantities of material on the site, and some of these can be, well, you wouldn’t want to put them on your cornflakes, ha ha, but still the question as always is one of quantifying risk.’

One of those morning interviews, then, when the interviewee’s time isn’t particularly important and there are unending minutes to fill. Slightly informative noise had to be created to cover the real interest, the pictures. Not the helicopter any more: footage from the ground, also shot before dawn, of fire crews directing inadequate-looking streams of water into a pulsing orange hell, the ground a reflecting pool in which coiled hoses wallowed.

My can was half empty already, its comforting weight gone, its top warm. I returned to the kitchen and topped it up from the one-third-full can I had found behind the lamp. Waste not, want not. The coldness and fizz of the remaining half of the fresh lager would take care of the flatness and warmth of the older stuff. But as a precaution, I poured it through a metal tea-strainer I kept beside the sink. In the past there had been instances when I had watched, horrified, as a glob of mould had slipped from a too-far-gone can into perfectly good beer. It was heartbreaking to have to pour it all down the sink. And there had been times when I had not washed it away, and they were even worse. But the strainer, found in a charity shop, had been a useful investment. This time nothing was intercepted, and the found beer frothed in a reassuring way. I had three cans in the fridge. That would probably do me for the morning.

‘Chances of a serious reaction are one in a million, one in 10 million really,’ the television voice was saying.

‘Ten million people in London,’ I said to the TV, ‘so one poor bastard …’

I tried to drink from the refilled can, but misaligned the aperture with my mouth, dribbling beer down the front of my T-shirt.

‘Shit.’

I ran the back of my wrist across my chin. The drilling, which had paused for breath, chose that moment to resume. I hated the pauses in the drilling more than anything, because they invited the thought that the noise might have stopped for good, which was seldom the case. The builders on the other side were now making their own contribution: a hammer-blow, perhaps metal against metal, which repeated eight or nine times, then stopped, then started again. Through the flat, from the direction of the street, came the throat-clearing sound of a diesel engine and a steady rattle of machinery.

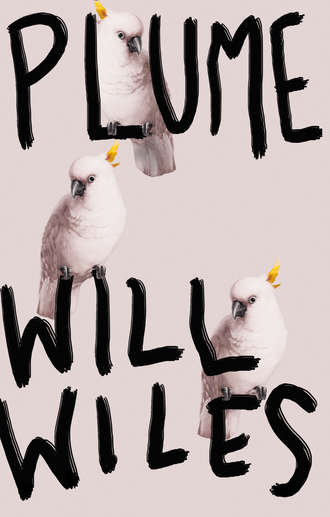

I threw the tree an angry glance. It was planted in next door’s back garden, another of their multiple insults. Through the splattered glass of the kitchen ceiling, I saw a flash of white in its black limbs.

A cockatoo, sitting in the tree, looking down at me.

No, not possible.

I changed my position to get a better view through one of the cleaner patches of grimy glass. The white shape ducked from view. I stepped back. There it was again – not a cockatoo, but a white plastic bag caught in the branches.

Pacing back to the sofa, I took my laptop from my shoulder bag and switched it on. The noise was intolerable, something had to be done. What, exactly, I did not know, and as a renter my options were limited.

To: dave@davestocktonlets.co.uk

Subject: Re: Re: NOISE

Hi Dave,

I had never met Dave, my landlord, but he was pleasant enough on email, if he replied. We had corresponded about the noise before and he made sympathetic sounds and said there was little he could do. But emailing him was my only outlet. The owners of the neighbouring houses were never around, of course – even when their homes weren’t the building sites they are now, I never saw them. Even if I could reach them, why would they do anything for me, a private tenant? I was simply nothing as far as they were concerned.

The email got no further than the salutation. Through the drilling, I heard an agitated rattling of my letterbox, then a triple chime on my doorbell. That special knock, this time in the morning, meant I knew at once who it was, and I groaned. Her, one of the ones from upstairs.

I wasn’t dressed but there was little point. The lager had soaked into the T-shirt and contributed to any pre-existing odours.

When I opened the front door I tried to stay mostly behind it. The icy air made me flinch. Her breath was fogging; she was dressed in running gear, a headband holding back dark blonde hair, her top a souvenir from the London School of Economics. She had been jogging on the spot, but stopped when I appeared, and took the headphones out of her ears.

‘Bella.’

‘Jack. Hi, you’re up!’ she said, surprised.

‘Every morning,’ I said. Bella had forced me out of bed on a couple of weekdays before the coming of the drills, and now she behaved as if I had a lie-in every day. If only I did. ‘Hard to sleep with the noise.’

‘I’ve been running,’ she said.

‘Cold,’ I said.

‘Are you in today?’

‘No, sorry.’

‘Really? Not at all?’ Bella said. She cocked her head to one side, a gesture that said: it’s OK, you can tell Bella, just admit that you will be lounging around in your flat all day and all will be well.

‘Really,’ I said. ‘I’m interviewing people.’

‘Ooh!’ she said, flashing her eyes wide. How did she get her lips to be so sparkly? Just looking at them made mine feel like sandpaper. The brick-dust was so thick in the air you could practically see it.

‘New job?’ she asked.

This took a moment to parse. ‘No. No! I’m interviewing people. For my job.’

She frowned. ‘To take over from you?’

I rubbed my eyes, feeling the grit in them. ‘No. I’m interviewing them for the magazine. The magazine I work for. In my job.’

‘Okey-dokey,’ she said, sceptical. ‘Will that take all day? Only we’re expecting a delivery.’

‘All day,’ I lied. ‘Can’t you get it delivered to your office?’

Her face pinched in consternation. ‘Ooh, no. It’s furniture.’

‘Sorry. Why did you arrange for it to be delivered today if you’re not going to be in?’

‘Well,’ she said with a little hauteur, ‘I expected you to be in.’

I felt that she had laid out a space for another sorry from me, but she wasn’t going to get it. ‘’Fraid not.’

She flicked her eyes downward and I made a small shuffle further behind the door.

Smiling brightly: ‘OK. You’re not dressed. I won’t keep you in the cold. Hope your interview goes well!’

I smiled back and started to close the door. She popped her earbuds back into her ears and turned towards the steps back up to the pavement.

‘Bella,’ I said, stopping her. ‘You guys own upstairs, don’t you?’

‘Sure,’ she said, as if startled by the implication that any other living arrangement could exist.

‘Have you complained to next door?’ I said. ‘Both next doors. About the noise. The building work.’

‘No,’ Bella said. ‘We’re out all day working, so …’

‘But, the dust,’ I said. ‘The dirt.’

She shrugged. ‘Thing is, it’s their property, isn’t it, so really they can do what they like with it.’

‘I guess so.’

In truth, I didn’t mind Bella as much as I might. She at least kept her low opinion of me heavily gilded with courtesy and cheer – I imagine she has no idea how she comes across. It’s him I can’t stand, Dan, her husband. A prime Mumford. I would happily murder Dan.

The front door sticks a little when it’s closed, and on occasion it needs a real bang to shut properly. This bang dislodged something from the letter flap, and this something fell with a turn that suggested the beat of a white wing.

A postcard from my parents: pretty toy-like buildings lined up on a picturesque quay. Could be anywhere. Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Stavanger, Lübeck. Five years ago, Dad had retired, and Mum had decided to join him. So this was victory, for them. They shared a belief – a widespread and wholesome belief – in the fixed path of virtue. School, as a path to University, as a path to a Proper Job (proper – an important qualifier, that). All this was the infrastructural spine that supported Marriage, Mortgage, Family and Responsibilities. But what was at the end of this path? What lay at the sun-touched horizon? What was the reward? Retirement, that’s what.

This might make them sound stuffy and orthodox – brittle mannequins of small-minded propriety cursed with a dissolute son. (My younger sister, a pharmaceutical chemist at Sheffield University, has done a little better at cleaving to the path.) Not true and not fair. They were never less than loving and supple in their accommodation of my occasional efforts to remove myself from the path. Their belief in the path manifested itself more subtly. Any unhappiness, for instance, could be diagnosed as deviation either past or planned. Miserable at school? I needed to treat it as a means to an end, the end being university. Restless and unmotivated at university? Again, its only purpose was as a step leading to the next step – head down, push on. Unable to save a mortgage deposit? Perhaps I should consider getting a more solid, more proper job – or moving back to Two Hours Away (by the faster train), the southern provincial city in which I was born. Love life problematic? Perhaps a Proper Job would yield more suitable candidates. None of this advice was delivered with self-righteousness or coercion, it was all meant honestly and kindly. And who could blame them for their belief in a system that had served them perfectly?

But just as the Correct Route Through Life had supplied its own built-in justifications, its completion had robbed it of purpose. My parents had spent their whole lives working dutifully, rewarded daily with the certitude that they were doing the right thing. The arrival of the real reward – comfortable retirement, two decent pensions, mortgage paid off, children through university and out of the house – had deprived them of the satisfaction of dogged, stately progress.

They went a little crazy.

When I was growing up, I never saw my parents argue. They disagreed at times, or frowned at each other, but never did they engage in that basic ritual of relationships, the big argument. Not in my sight, anyway. I have no inkling of what script discussions or creative disputes went on behind the scenes of their performance as Mum and Dad. But on stage, they were pros.

In the first year after their retirement, they argued: long, flamboyant arguments with epic scope, stirring chiaroscuro and elaborate, intertwined plots and subplots. Late in life, they found that they shared a gift for holding a really poisonous row.

They supplied their own reviews of these arguments. Ever since I turned eighteen, Dad had routinely taken me out for ‘a pint’ at the local pub. A pint, precisely: two half-pints of bitter, followed by a further two ordered with hints of wicked indulgence and declamations that that had never been the plan. After his retirement, those drinks turned into discussions of the arguments. ‘Your mum and I have been arguing a lot,’ he would say, every time, as if he didn’t say the same thing every time. He never criticised her, and I truly believe that it would never even occur to him to do so. But he would sadly acknowledge the fact of the arguments, without giving the slightest detail as to what might be causing them, and expect me to be sympathetic.

(My sister reported that she was getting the exact same from Mum, often at precisely the same moment. Mum did criticise Dad, but only in the vaguest, most all-encompassing terms: ‘Your Father!’, uttered as if his very existence was an affront we had all quietly tolerated for too long.)

Then, a transformation. After about a year of arguments, including the hellish Christmas of 2012, my parents decided they needed a holiday. For twenty-five years, French beaches had known their presence in the summer. Their knowledge of the French coast was probably rival to that of Allied high command, June 1944. But this time, in the spring of 2013, they went on a city break, to Brussels on the Eurostar.

They stayed four nights and I received three postcards. Dad ate a horse steak. Mum ate a waffle sold from a van. They were photographed in front of the Atomium, the Palais de Justice, the Tintin Museum, the restaurant where Dad ate the steak, the van from which Mum purchased the waffle, and the headquarters of the European Commission.

A mania took hold. An addiction, maybe. No city in Europe was safe. It didn’t really matter where this postcard came from, and I already knew the gist of what was written on the back. It would join a small pile of very similar postcards on the kitchen counter, next to a cork board thoroughly covered with a bright collage of classical columns, Gothic spires, Moorish palaces, Dutch gables and high pitched Nordic roofs.

The era of arguments came to an end. So began the era of city breaks.

Standing in the icy doorway for so long had completely thrown me off my stride. I opened another can of Stella, forgetting that I already had one on the go.

All the cans in the fridge were empty by the time I left the house, and so were the half-empty cans I had found. I would have to pick up more, but then I would have needed to make a run in any case. Three cans or fewer was completely insufficient, dangerous. The horrible thought that there was no alcohol in the flat would be at or near the front of my mind all day.

In other regards the morning was going well. I had showered, put on (mostly) clean clothes, and set out at a reasonable time. My bag was double-checked for all the things I needed: two digital voice recorders, my old one and my new one, and spare batteries for them. After the recent disaster with F.A.Q., I was taking no chances.

Also in the bag were Pierce’s books: two novels, the mugging book, and the cash-in collection of non-fiction that his publisher had put out the Christmas that the mugging book was at the top of every broadsheet ‘books of the year’ list. Actors, MPs, television historians, baking competition hosts, they all exerted themselves to overstate how luminous, powerful, searing, important, draining, life-affirming, etcetera, etcetera they had found Night Traffic. I felt quite resentful about all this, because I had been reading Pierce for years. My copy of Night Traffic was the softback Panhandler Press edition with the cheap cover art, not the classy Faber edition that appeared when the award shortlists and reviews started to pile up, and which is still inescapable on the Tube.

I had been reading Pierce since his first novel, Mile End Road, came out in 2009. This was a fairly conventional story of twenty-somethings finding love, losing it, finding it again and then losing it for a second and final time. But the few reviews it received praised its rendering of twenty-first-century London life and its (at the time) unusually realistic depiction of the mobile phone and social media habits of young Londoners. It was longlisted for a couple of prizes and did not trouble any bestseller charts.

Pierce’s second novel, Murder Boards, had the good fortune to appear just before the 2011 riots. To capitalise, the post-riot paperback was given a sensational cover, with a movie-like strapline: THE CITY IS ABOUT TO EXPLODE. This bore little relation to its contents, 500 pages of non-linear narrative and cut-up technique told from the multiple viewpoints of its spectral cast of characters. It was concerned – obsessed, really – with missing persons and unresolved crimes, and steeped in police jargon and the imagery and phrasing of TV news. At times, it appeared to be deliberately opaque and confusing, as if the reader were an investigator confronted with contradictory accounts of events and inscrutable enmity between characters, between reader and author, between author and reality, with the objective truth of the past unknowable. To give up on Murder Boards was to play Pierce’s game, to take on the role of the indifferent bystander, the grazing TV viewer, the desensitised inquisitor, the impatient and unsympathetic bureaucracy. The reader’s natural frustration with a long and frankly exhausting experimental novel was thus subverted. Read to the end or put the book down unfinished – either way, Pierce won. Reviewers were divided. One-third of them hailed Pierce as a genius, another third called him a charlatan. The remainder made it obvious they did not understand the book, and maybe had not even finished it, by playing it safe with cautious praise.