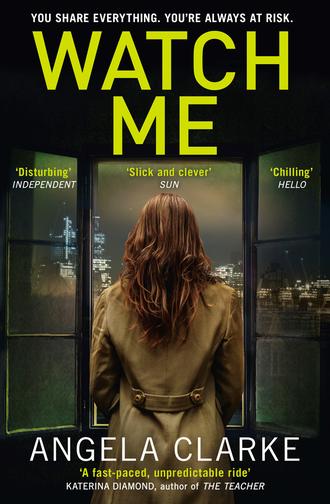

Полная версия

Watch Me

‘You came to me because you know Saunders won’t agree to some consultant being brought in to a case that involves the guv. Because you think I’m a soft touch?’

Crap. ‘I don’t think that, sir. I have the utmost respect for you. You’re a legend in the force.’ She felt her face blush.

‘You mean I’m old, lass?’ Chips chuckled.

‘No, not that. You’re not old. I …’ The chance of getting Freddie’s help was slipping through her fingers. She couldn’t tell any of the team she was the link between the two victims. Not until she knew it wasn’t some ghastly coincidence. But she could tell Freddie. Freddie could help. ‘I just want to find Lottie. Safe.’

‘We’re already treading a fine line, lass, having Burgone stay. Saunders is jumpy. He likes doing things by the book.’ He paused. ‘Then again, I thought you did too.’

Her face coloured again. ‘I do. I really believe Freddie could help. I’m not asking for her to be brought onto the team. I can show her the intelligence on the notes, see what she makes of it. If this is a copycat, then it’s a copycat of a serial killer.’

His face clouded. ‘Then this might just be the start.’

The threat hung in the air between them.

‘Okay,’ he relented. ‘She can look at what we’ve got, but it’s got to be off record: there’s no budget for this. She can’t be expecting money.’

‘Not a problem.’ She hoped. Freddie may come off rough round the edges, but she had a big heart.

‘This stays between you and me. No mention to Saunders, no mention to the guv, okay?’

‘Yes, sir.’ She reasoned she was merely protecting her source: Freddie.

‘I don’t want any difficult questions from the CPS. Got it?’

She nodded.

‘If we were talking about anyone other than Jack’s sister I wouldn’t be authorising this.’ Chips thrust the notes back her. His face was closed, stern. He was angry she’d put him in this position.

‘If it was anyone other than the guv’s sister, I wouldn’t be asking.’ That was the truth. If Nasreen was the link between the two girls then one person was already dead because of her. She had to follow this lead, no matter where it led. Saunders and Burgone couldn’t find out about Freddie. Saunders was itching to find fault with her. If he knew about Freddie he might start digging, and then how long would it be before he uncovered that she, Freddie and Gemma had all gone to school together? That they had been the best of friends. That Freddie and she had nearly driven Gemma to her death. She had no doubt he’d use that to leverage her out. It had to stay a secret for her own safety too.

Chips looked at his watch. ‘You’ve got three hours. Max. Make it count, Cudmore.’ Three hours to speak to Freddie. Three hours to interview Chloe’s friends. Three hours to work out if she really was the link. Three hours to work out if she was to blame for Lottie’s predicament. She could hear Chips’s watch ticking as she hurried away. This is it. No room for error. 10.55 a.m. T – 22 hours 25 minutes. Make it count.

Chapter 8

Wednesday 16 March

11:45

T – 21 hrs 45 mins

Freddie Venton stared at the ceiling of her childhood bedroom. A hairpin crack ran from the top of the rose-patterned wallpaper (her mum’s choice) and slithered across the ceiling. Mum had been at the doctors for her blood pressure, she was going into the school late today. Freddie could hear the sound of her work pumps moving across the hallway. She shut her eyes and slowed her breathing, like she used to when she was young, reading late under the covers.

‘Love?’ her mum whispered. ‘Are you awake?’

Yes, I’m awake! I’ve been awake since blood poured into my eyes. Since sleeping meant the dreams came. And they couldn’t come. She couldn’t relive it. She couldn’t sleep. So she pretended. Her mum had enough on her plate with her dad’s antics; she didn’t need any more worry.

There was a rattle as her mum put a tray down, not wanting to intrude, but not wanting her daughter to starve either. Freddie could sense her standing there. A broken husband and a broken child – life had not been kind to Mrs Venton. ‘Happy birthday, love,’ she whispered, pulling the door gently to.

Not long now. Freddie heard the gruff grunt of her father, his articulation lost to the alcohol.

‘Do you think we should try the doctor again?’ her mum stage-whispered.

Another grunt.

‘It’s been weeks. She’s barely eating. She hasn’t said more than a few words.’ Freddie heard the worry in her mum’s voice. She wanted to tell her it was all going to be all right. But she couldn’t. Instead, she began to count the roses on the wall again. ‘This can’t go on,’ her mum was saying. Twenty-nine, thirty, thirty-one …

The front door opened and closed, and Freddie heard her mum’s Corsa start. She listened for the jingle of the keys. A whistle for the dog. The door opened – Dad was leaving for the pub. She waited in case he’d forgotten anything. One minute, two minutes, three minutes … Then she threw the duvet off, shuffling across to the tray. Sandwiches. Marmite and cucumber: her favourite when she was little. There were a couple of cards tucked under a present. Freddie picked up the small weighty rectangle, the wrapping paper covered in birds, and read the tag:

Thought I’d get this fixed for you.

Happy Birthday, love Mum and Dad xxx

She knew what it was. Placed it unopened on the tray.

She padded downstairs and into the room at the back of the house. Her father’s den: a boxy room, with a raised, jutting windowsill, as if the builder had forgotten to put the bottom part of the wall in. The blue curtains were drawn. Mum didn’t come in here. Freddie didn’t come in here. The small coffee table and the blue sofa bed were covered in used glasses. Dad slept in here sometimes, when Mum couldn’t take it anymore. It smelled stale. Sour. Sitting on the sofa, she stroked the grooves where her dad sat. Closed her eyes. Tried to remember what he was like before. The good memories were fainter now. Him swinging her round in the garden, her giggling uncontrollably. Her and Nas cycling up and down the path outside their house. A trip to Thorpe Park. She tried to remember what happiness felt like. But a heavy blanket had settled over Freddie the day she was attacked; she’d felt nothing but thrumming anxiety since.

The doorbell sounded. She froze, as if they could see what she was doing. The guilt of the emptiness.

The doorbell rang again. Longer. More insistent. ‘Hang on!’ she shouted. When did she last speak that loud? She ran to the door. The dark blur of the person standing behind it was fractured by the geometric glass pattern. She opened it. Fought the urge to dissolve into tears. There on the doorstep in her smart black trouser suit was Nasreen Cudmore.

‘Hello, Freddie.’

Chapter 9

Wednesday 16 March

12:20

T – 22 hrs 10 mins

‘You going to invite me in?’ Nas’s face looked as it always had: high cheekbones carved into flawless skin, brown eyes sparkling, dark hair hanging in a velvet tuile from her hairband. Beautiful, but detached. There was something new in her eyes: a nervousness, a quick sweep from one side of the room to the other, as if she was scanning the horizon, checking the exits. Then it was gone, replaced with the face Freddie knew Nas used to greet the general public. Warm, effusive, persuasive.

‘What you doing here?’ It was the middle of the day. Why wasn’t Nas at work? This was a long way from the East End’s Jubilee police station. Skyscrapers cut like a bookmark through the pages of her memory. Highlighting moments of pain. That’s far away. You’re safe here. Safe.

‘I need to talk to you.’ Nas’s gaze flickered to her hand, and Freddie realised she was gripping the door handle so tight her knuckles were stretched white. She let go.

‘You best come in then.’ She led her into the spotless lounge. Her mum’s OCD hung in the air, mingling with the smell of polish. Trying to scrub out the stains in her life. ‘Bit different from my usual style.’ She tried to sound lighthearted, but saw Nas take in the perfectly spaced ornaments on the dresser. Did she remember when Dad broke them all? Smashed them while Freddie and Nas told ghost stories by torchlight under a duvet; Nas scared, Freddie flippant about the shouts and screams coming from downstairs. As if it was normal. In a way it was. That was a long time ago. Different house. Different ornaments. Different life.

They sat on the dark brown leather DFS sofas, facing each other. Nas perched on the edge of her seat, still in her coat, her hands clasped in her lap. Her nails shiny with clear polish. Freddie glanced at her own mismatched pyjamas. Nas looked at her scar. It throbbed in response. It’s all in my mind. ‘Do you want a cup of tea or something?’

‘No. Thank you.’ Nasreen smiled, but it didn’t reach her eyes, as if she were talking to a child. She was uneasy in her presence. ‘How are you doing, Freddie?’

‘Nightmares, no sleep, I’m trapped in suburbia, you know.’ It was supposed to be a joke, but her words were brittle, cracking ice underfoot. A car drove past outside, the rumble of the engine underscoring the silence that engulfed the room. Freddie’s breathing sounded loud, a rasping echo of the car’s exhaust.

Nas shuffled in her seat, her polished heels squeaking against each other. She cleared her throat. ‘I need your help. With a case.’

‘No.’ Freddie was shocked at the word. She hadn’t planned to say it. It felt as though someone was speaking through her, someone she’d forgotten existed. How dare Nas just show up and say that! How dare she just walk in and act as if nothing had happened. She wanted her gone. Standing, she caught the edge of the veneered coffee table with her knee. A weird, unfamiliar feeling spread through her. Pain. A short, sharp stab. She felt it. She was thawing. Melting. Her body tried to override it. ‘Well, if you don’t want a drink, then …’ She wanted to shout: We’re done. We’re finished. Get out! But she’d sound crazy. Was she going crazy? Maybe. Maybe she already had. But she didn’t want to show Nas that. ‘I think I’ll make myself a coffee.’

Nas didn’t move. Freddie could see what was dancing around behind her eyes when she’d scanned the room: desperation.

She was supposed to be safe here. Hidden. No one would think to look in a suburban backwater. Down a winding country lane. What’s out there? She could feel the isolation of the house. All four walls exposed to the elements. Is he back? ‘I can’t,’ she said, her hand shooting to her forehead. Her scar felt coarse and bumpy: a warning to never get too close again.

Nas produced a brown envelope and placed a photo of a smiling blonde girl on the coffee table. Don’t look at it. ‘This is Chloe. On Friday, 12 March at 8 p.m. she sent this photo of her suicide note via Snapchat to her friends and sisters.’ Nas pulled a photo of a printed letter from the envelope. Freddie walked to the bay window; straightened her parents’ 1970s wedding photo.

Nas continued, unperturbed. ‘The note warned that the body would not be found until twenty-four hours later.’ Freddie looked at her mum’s smile. So happy. So long ago. Before life had taken all hope from her. ‘At just after 8 p.m. on Saturday, 13 March, Chloe’s body was found in Wildhill Wood.’

‘I’m sorry for the girl, Nas. Course I am. But it’s nothing to do with me.’ All her edges felt raw, as if every nerve ending had been exposed. She needed her to leave.

The leather of the sofa creaked. ‘Chloe was Gemma’s sister.’

Freddie spun, catching her parents’ photo; it clattered backwards against the windowsill. ‘Why tell me this? Haven’t you put me through enough?’

‘This morning at 9.30 a.m. a second Snapchat suicide note was received from Lottie Burgone.’ Nas’s tone was calm.

Freddie picked up the photo, slamming the frame down onto the wood.

‘We have reason to suspect someone might have taken Lottie. Look at the note. It sounds like a threat.’ Nas thrust two photos at her.

She grabbed them so they wouldn’t fall. ‘I can’t.’ Her eyes scanned the words. I feel calmer …. the right thing … the pain will fade.

‘She’s eighteen, Freddie.’ Nas dragged her palm back over her hair.

The words pulled on Freddie’s eyes. You have 6 seconds to read this and 24 hours to save the girl’s life. Nas said 9.30 a.m. Over three hours ago. I can’t.

‘Lottie’s the sister of my new boss.’ Nas shook her head, as if it wasn’t real.

‘I’m sorry.’ Freddie handed the photos back. She didn’t want to touch them. Didn’t want to know this. She just wanted to be left alone. Freddie saw the shadows under Nas’s eye make-up. She saved your life. You owe her. I can’t … An eighteen-year-old girl … Gemma’s sister. Gemma, who told you never to contact her again. Her chest constricted, her windpipe closing. The words, the images, started to tumble down on her. Freddie turned away. Stared out the window. One leaf, two, three, four, five …

Nas gathered up the photos – Gemma’s dead sister – and put them back in the envelope. Outside the light started to shift, a slow descent into the shadows. ‘You don’t need me. You’ve got cops. Trained professionals.’ Freddie wasn’t sure who she was talking to. ‘I’m seeing a counsellor. She wouldn’t like this. I’m not ready.’ The fields around her parents’ house stretched away from the single-track road. If she listened hard, blocked everything else out, she could just make out the motorway.

Chapter 10

Wednesday 16 March

12:30

T – 21 hrs

Nasreen wanted to grab Freddie. Shake her. Beg her. The devastation on Burgone’s face floated before her; jarring with the images of gasped pleasure last night. His toned, slender torso. His arms around her. Her heart screamed at Freddie to help. But what could this broken shell of a woman do? She looked awful. She’d lost weight – it didn’t suit her. Dark shadows were etched into her face. And the scar. She thought it would have healed. Faded. But it’s belligerently, defiantly there. The most real part of her. There was nothing left of the girl she knew. This had been a mistake.

‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘I shouldn’t have come.’ She’d look into getting Freddie some help when this was over. The grim thought of what the next twenty-four hours might hold was destabilising.

Her stomach churned at the thought of explaining this to Chips. So much for impressing him: she’d wasted time and resources, roping in DC Green on a wild goose chase. Her phone had full signal, but no missed calls. No updates from the office. No breakthrough. They had twenty-one hours to find Lottie. They needed a lead. Another message. Something.

Freddie was silhouetted against the net curtains, hugging herself tight across her chest, her cartoon character pyjama top hanging off of her. Nasreen didn’t like to guess when she’d last washed her hair. She should have come sooner. As a friend. She didn’t know things were this bad. She would have made time, if Freddie or her mum had called her. Wouldn’t she? She swallowed her own doubt and guilt.

‘Do you remember the year it snowed and school was closed for four days?’ Freddie was staring out the window as she spoke. ‘We made snow angels at the bus stop.’

Nasreen’s chest pinched. This was her fault. Freddie should never have been involved in the previous case. She was a civilian. Not trained. She had put her childhood friend in the path of danger. It was a gamble, and Freddie had lost. When this was over she’d come back. Try and get her to have a shower, take her out for a walk.

Nasreen tucked the envelope into her jacket: the only clues she had, resting against her heart. ‘Take care of yourself, Freddie.’ The black leather gloves she’d been issued with when she’d joined the force creaked as she pulled them on and made for the door. She’d call Chips while DC Green drove. This was not going to be fun.

‘It’s not him, is it?’ Freddie asked.

Nasreen paused. ‘Who?’

Freddie turned, the faraway look gone, her eyes focused. She pushed her glasses up the bridge of her nose. ‘Apollyon.’

Nasreen stared at her. She’d barely looked at the notes …

‘It’s an acrostic – you know that, right?’ She tilted her head to one side, her hair, longer now, falling in jagged corkscrews. Her face had a familiar look: the one that came before she announced some great discovery. Fish don’t have fingers. Grown-ups make babies by sexing. Hayley Mandrake’s sister has done it behind Morrisons. Hundreds of Freddie’s revelations cascaded through Nasreen’s memory, half of which were declared dud, tossed away as Freddie’s mind raced to the next adventure. The light had switched back on behind her childhood friend’s eyes.

‘Yes,’ said Nasreen. ‘But it can’t be Apollyon. He’s inside. Locked up. Solitary. No internet access.’

Freddie nodded. Circuits flashed, connecting above her head. ‘Gemma’s sister. Your boss’s sister. Apollyon.’

It wasn’t a question, but she nodded anyway. Keen not to break the chain. She knew what she was asking her to do.

‘You told them yet?’ Freddie raised her eyebrows.

There was no way she could know about Burgone – could she? Nasreen’s ears grew warm. ‘Told who what?’

‘That you’re the link.’

The relief was fleeting. ‘I’ve told them the relevant bits. About the Apollyon link in the notes.’ Freddie would never meet the team. They were highly unlikely to bump into each other in a social situation. Chips and Saunders liked pubs, with real ale and loud inappropriate jokes. And Freddie liked … being nocturnal? She’d get Freddie’s insight and then get back to the unit, with neither party ever being the wiser. ‘The name on the notes is circumstantial, but we could be looking at some kind of copycat.’ The idea of another serial killer sloshed through her stomach like acid. ‘It’s not a pattern. I just want to double check. If the same person is involved in Lottie’s disappearance then we might find something in Chloe’s case that leads us to them.’

‘Apollyon used Twitter, and now he’s shifted to Snapchat,’ mused Freddie.

‘We know the Apollyon case better than anyone else.’

‘I am the case!’ Freddie pointed at the gouged scar on her forehead.

If these two girls had been abducted, killed, because of Nasreen, then she had to fix it. Had to. Freddie was her best shot at that. She was wrapped up in this tighter than anyone else.

‘Am I in danger?’ Freddie’s face shifted, threatening to withdraw.

Of course she’d want to know that! Nasreen should’ve immediately reassured her. ‘There’s no evidence to suggest you’re at risk.’

‘What about the people I know? Mum? My dad?’ Freddie folded her arms over her chest.

‘There’s no reason they should be. You don’t know DCI Burgone, or his sister, Lottie. Do you?’ The thought that Freddie might somehow know Burgone stung, though she wasn’t sure why.

‘Don’t think so.’

‘Okay. If there is any link then, it’s me.’ It was the first time she’d verbalised it. Suddenly, it was no longer an abstract concern. The events of the last twenty-four hours slipped through her fingers like uncooked rice. Wishing things were different and that she could stay here with Freddie was pointless. ‘Perhaps the Apollyon word cropping up in both notes is coincidence, I just …’

‘Feel it in your gut?’ Freddie had a glint of mischief in her eye. She put great faith in intuition, using it more than once to sanction a bad idea. ‘I didn’t think you went in for all that wishy-washy stuff, Nas. You’re a woman of facts, evidence, procedure. You follow the letter of the law.’ She gave a mock salute.

‘I still think homeopathy is a load of rubbish, if it makes you feel better.’ This was more like the Freddie she knew and loved to bicker with.

‘Doesn’t everyone?’

Freddie was deflecting. Possibly stalling for time. That meant she hadn’t made her mind up yet.

‘Will you help?’

They stared at each other. The tick of the carriage clock on the mantelpiece filled the silence. Tick. Tick. Tick. Tick. Nasreen didn’t have anything left to say. She was asking a lot of her friend, knew it was irresponsible. But asking for Freddie’s help was the only thing she could think of. T – 20 hours 38 mins. Tick. Tick. Tick.

Freddie looked round, as if she were seeing the room for the first time. ‘Give me five.’ She tugged at her top. ‘I need a shower.’

Nasreen could have hugged her. Should she hug her? She stepped forward, faltered, and stopped. She’d taken too long to decide, and Freddie was already at the stairs. That kind of gesture – a hug – belonged to their past. When they were teen BFF’s, or whatever it was called now. ‘I’ll wait in the car.’ She felt better. As if just having Freddie on board changed everything. It was a familiar feeling, she realised, one from childhood. From when she’d stood shoulder to shoulder with Freddie in the playground. The mouthy girl had protected her, taught her to fight back, speak up. She’d had this invincibility: a gift. Nasreen now understood it was bravado, bolstered from Freddie’s troubled home life. You had to speak up to be heard over a drunken father. You had to fight back. But it was still a powerful feeling: two is better than one. They could do anything together. She wanted to give that reassurance, that same feeling to this Freddie. The pale, thin, damaged one. ‘They get better, by the way.’

‘What?’ Freddie was halfway up the stairs, school photos of her in her grey-and-red uniform on the wall behind her.

‘The nightmares.’ Nasreen’s eyes rested on the image of the eight-year-old Freddie. How old they’d been when they’d first met. Two young girls, skipping in the playground. Eating strawberry yoghurts with plastic spoons. Running with their hoods on their heads, their coats flying behind them like capes. Their whole lives ahead of them.

‘Good to know,’ she said over her shoulder. And Freddie Venton walked back into the flames.

Chapter 11

Wednesday 16 March

13:05

T – 20 hrs 25 mins

Freddie shook the towel from her hair and opened the wardrobe in her room. Inside, unopened, were all the cardboard boxes that had been returned to her by the police. After what had happened, her room – the living room in her flat – had become a crime scene. Ironic really, given that it was her breaking into a crime scene in search of a news story that had kickstarted all of this. She tried to think back to that person: the one who was a journalist, writing reams of articles – mostly for free – for online newspapers. It was like imagining a character in a TV show or a film. The threads linking her to that person had been severed. And that life, her life, had been sealed in boxes and hidden away.

Pulling down the first box, she ripped off the tape, rummaging through sweatshirts, jean shorts, knickers … the detritus of her former self. Nope. Not there. She opened the next: full of paper takeaway cups bagged in forensic plastic. They had to be kidding. Why keep this crap? Bloody police – always so proper. She shoved it aside and opened the next. Finally! She pulled out her skinny jeans. Black. And under them her DM boots. Black. The jeans were loose, so she rolled the waistband to sit low on her hips. She could do with a pizza. She was hungry. When had she last been hungry? Pulling on her boots, she felt the familiar tilt and wear to the leather, shaped on the streets of London. They were made for city streets, not country lanes or, even more insulting, suburban pavements. Was it hunger or was it excitement? There was a strange sensation in her stomach: fizzing. Her body felt different, and it wasn’t just that her checked red shirt and purple hoodie hung off her, unexpected gaps between her skin and the material. It was that she felt it at all. It had started downstairs with that warm, damp feeling inside, and it had spread through her, tingling her fingers, wriggling her toes. A switch had been flicked. She’d experienced a surge. Was she ready for this? Could she leave this house? This street? This town? Could she get in a car with Nas and drive back to London? She could – should – call her counsellor. And do what? Talk about her bloody feelings? There was a girl out there who needed her help. Who gave a toss about her feelings? She shoved the small present from her mum, still wrapped, into her pocket. Running down the stairs, she grabbed her denim jacket on the way.