Полная версия

Towards Zero

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Collins, The Crime Club 1944

Towards Zero™ is a trade mark of Agatha Christie Limited and Agatha Christie® and the Agatha Christie Signature are registered trade marks of Agatha Christie Limited in the UK and elsewhere.

Copyright © 1944 Agatha Christie Limited. All rights reserved.

www.agathachristie.com

Cover by designedbydavid.co.uk © HarperCollins/Agatha Christie Ltd 2017

Agatha Christie asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008196318

Ebook Edition © February 2017 ISBN: 9780007422890

Version: 2017-04-17

Dedication

To Robert Graves

Dear Robert,

Since you are kind enough to say you like my stories, I venture to dedicate this book to you. All I ask is that you should sternly restrain your critical faculties (doubtless sharpened by your recent excesses in that line!) when reading it.

This is a story for your pleasure and not a candidate for Mr Graves’ literary pillory!

Your friend,

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

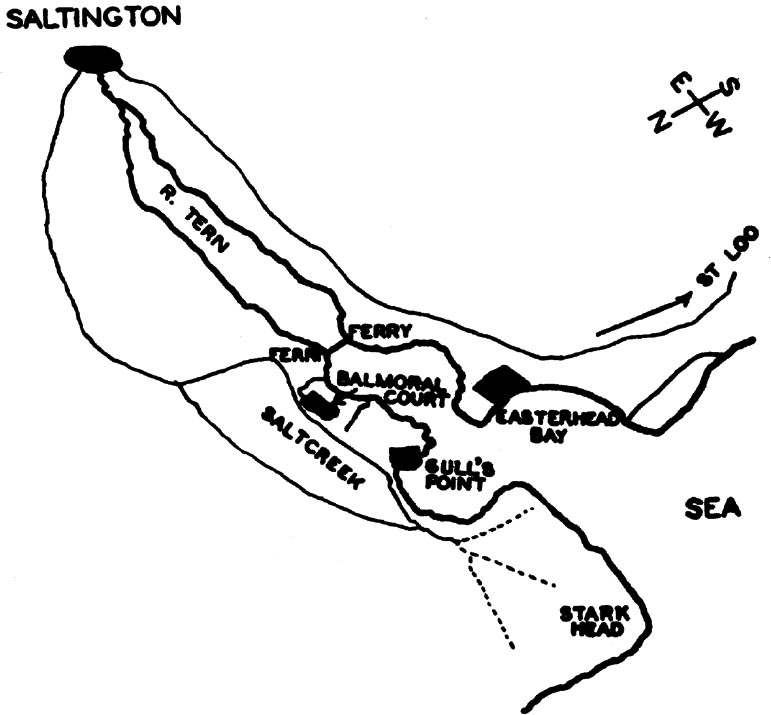

Map

Prologue: November 19th

‘Open the Door and Here are the People’

Snow White and Red Rose

A Fine Italian Hand …

Zero Hour

Also by Agatha Christie

About the Publisher

Map

Prologue

November 19th

The group round the fireplace was nearly all composed of lawyers or those who had an interest in the law. There was Martindale the solicitor, Rufus Lord, KC, young Daniels who had made a name for himself in the Carstairs case, a sprinkling of other barristers, Mr Justice Cleaver, Lewis of Lewis and Trench and old Mr Treves. Mr Treves was close on eighty, a very ripe and experienced eighty. He was a member of a famous firm of solicitors, and the most famous member of that firm. He had settled innumerable delicate cases out of court, he was said to know more of backstairs history than any man in England and he was a specialist on criminology.

Unthinking people said Mr Treves ought to write his memoirs. Mr Treves knew better. He knew that he knew too much.

Though he had long retired from active practice, there was no man in England whose opinion was so respected by the members of his own fraternity. Whenever his thin precise little voice was raised there was always a respectful silence.

The conversation now was on the subject of a much talked of case which had finished that day at the Old Bailey. It was a murder case and the prisoner had been acquitted. The present company was busy trying the case over again and making technical criticisms.

The prosecution had made a mistake in relying on one of its witnesses—old Depleach ought to have realized what an opening he was giving to the defence. Young Arthur had made the most of that servant girl’s evidence. Bentmore, in his summing up, had very rightly put the matter in its correct perspective, but the mischief was done by then—the jury had believed the girl. Juries were funny—you never knew what they’d swallow and what they wouldn’t. But let them once get a thing into their heads and no one was ever going to get it out again. They believed that the girl was speaking the truth about the crowbar and that was that. The medical evidence had been a bit above their heads. All those long terms and scientific jargon—damned bad witnesses, these scientific johnnies—always hemmed and hawed and couldn’t say yes or no to a plain question—always ‘in certain circumstances that might take place’—and so on!

They talked themselves out, little by little, and as the remarks became more spasmodic and disjointed, a general feeling grew of something lacking. One head after another turned in the direction of Mr Treves. For Mr Treves had as yet contributed nothing to the discussion. Gradually it became apparent that the company was waiting for a final word from its most respected colleague.

Mr Treves, leaning back in his chair, was absent-mindedly polishing his glasses. Something in the silence made him look up sharply.

‘Eh?’ he said. ‘What was that? You asked me something?’

Young Lewis spoke.

‘We were talking, sir, about the Lamorne case.’

He paused expectantly.

‘Yes, yes,’ said Mr Treves. ‘I was thinking of that.’

There was a respectful hush.

‘But I’m afraid,’ said Mr Treves, still polishing, ‘that I was being fanciful. Yes, fanciful. Result of getting on in years, I suppose. At my age one can claim the privilege of being fanciful, if one likes.’

‘Yes, indeed, sir,’ said young Lewis, but he looked puzzled.

‘I was thinking,’ said Mr Treves, ‘not so much of the various points of law raised—though they were interesting—very interesting—if the verdict had gone the other way there would have been good grounds for appeal, I rather think—but I won’t go into that now. I was thinking, as I say, not of the points of law but of the—well, of the people in the case.’

Everybody looked rather astonished. They had considered the people in the case only as regarding their credibility or otherwise as witnesses. No one had even hazarded a speculation as to whether the prisoner had been guilty or as innocent as the court had pronounced him to be.

‘Human beings, you know,’ said Mr Treves thoughtfully. ‘Human beings. All kinds and sorts and sizes and shapes of ’em. Some with brains and a good many more without. They’d come from all over the place, Lancashire, Scotland—that restaurant proprietor from Italy and that school teacher woman from somewhere out Middle West. All caught up and enmeshed in the thing and finally all brought together in a court of law in London on a grey November day. Each one contributing his little part. The whole thing culminating in a trial for murder.’

He paused and gently beat a delicate tattoo on his knee.

‘I like a good detective story,’ he said. ‘But, you know, they begin in the wrong place! They begin with the murder. But the murder is the end. The story begins long before that—years before sometimes—with all the causes and events that bring certain people to a certain place at a certain time on a certain day. Take that little maid servant’s evidence—if the kitchenmaid hadn’t pinched her young man she wouldn’t have thrown up her situation in a huff and gone to the Lamornes and been the principal witness for the defence. That Guiseppe Antonelli—coming over to exchange with his brother for a month. The brother is as blind as a bat. He wouldn’t have seen what Guiseppe’s sharp eyes saw. If the constable hadn’t been sweet on the cook at No 48, he wouldn’t have been late on his beat …’

He nodded his head gently:

‘All converging towards a given spot … And then, when the time comes—over the top! Zero Hour. Yes, all of them converging towards zero …’

He repeated: ‘Towards zero …’

Then gave a quick little shudder.

‘You’re cold, sir, come nearer the fire.’

‘No, no,’ said Mr Treves. ‘Just someone walking over my grave, as they say. Well, well, I must be making my way homewards.’

He gave an affable little nod and went slowly and precisely out of the room.

There was a moment of dubious silence and then Rufus Lord, KC, remarked that poor old Treves was getting on.

Sir William Cleaver said:

‘An acute brain—a very acute brain—but Anno Domini tells in the end.’

‘Got a groggy heart, too,’ said Lord. ‘May drop down any minute, I believe.’

‘He takes pretty good care of himself,’ said young Lewis.

At that moment Mr Treves was carefully stepping into his smooth-running Daimler. It deposited him at a house in a quiet square. A solicitous butler valet helped him off with his coat. Mr Treves walked into his library where a coal fire was burning. His bedroom lay beyond, for out of consideration for his heart he never went upstairs.

He sat down in front of the fire and drew his letters towards him.

His mind was still dwelling on the fancy he had outlined at the Club.

‘Even now,’ thought Mr Treves to himself, ‘some drama—some murder to be—is in course of preparation. If I were writing one of these amusing stories of blood and crime, I should begin now with an elderly gentleman sitting in front of the fire opening his letters—going, unbeknownst to himself—towards zero …’

He slit open an envelope and gazed down absently at the sheet he abstracted from it.

Suddenly his expression changed. He came back from romance to reality.

‘Dear me,’ said Mr Treves. ‘How extremely annoying! Really, how very vexing. After all these years! This will alter all my plans.’

‘Open the Door and Here are the People’

January 11th

The man in the hospital bed shifted his body slightly and stifled a groan.

The nurse in charge of the ward got up from her table and came down to him. She shifted his pillows and moved him into a more comfortable position.

Angus MacWhirter only gave a grunt by way of thanks.

He was in a state of seething rebellion and bitterness.

By this time it ought to have been over. He ought to have been out of it all! Curse that damned ridiculous tree growing out of the cliff! Curse those officious sweethearts who braved the cold of a winter’s night to keep a tryst on the cliff edge.

But for them (and the tree!) it would have been over—a plunge into the deep icy water, a brief struggle perhaps, and then oblivion—the end of a misused, useless, unprofitable life.

And now where was he? Lying ridiculously in a hospital bed with a broken shoulder and with the prospect of being hauled up in a police court for the crime of trying to take his own life.

Curse it, it was his own life, wasn’t it?

And if he had succeeded in the job, they would have buried him piously as of unsound mind!

Unsound mind, indeed! He’d never been saner! And to commit suicide was the most logical and sensible thing that could be done by a man in his position.

Completely down and out, with his health permanently affected, with a wife who had left him for another man. Without a job, without affection, without money, health or hope, surely to end it all was the only possible solution?

And now here he was in this ridiculous plight. He would shortly be admonished by a sanctimonious magistrate for doing the common-sense thing with a commodity which belonged to him and to him only—his life.

He snorted with anger. A wave of fever passed over him.

The nurse was beside him again.

She was young, red-haired, with a kindly, rather vacant face.

‘Are you in much pain?’

‘No, I’m not.’

‘I’ll give you something to make you sleep.’

‘You’ll do nothing of the sort.’

‘But—’

‘Do you think I can’t bear a bit of pain and sleeplessness?’

She smiled in a gentle, slightly superior way.

‘Doctor said you could have something.’

‘I don’t care what doctor said.’

She straightened the covers and set a glass of lemonade a little nearer to him. He said, slightly ashamed of himself:

‘Sorry if I was rude.’

‘Oh, that’s all right.’

It annoyed him that she was so completely undisturbed by his bad temper. Nothing like that could penetrate her nurse’s armour of indulgent indifference. He was a patient—not a man.

He said:

‘Damned interference—all this damned interference …’

She said reprovingly:

‘Now, now, that isn’t very nice.’

‘Nice?’ he demanded. ‘Nice? My God.’

She said calmly: ‘You’ll feel better in the morning.’

He swallowed.

‘You nurses. You nurses! You’re inhuman, that’s what you are!’

‘We know what’s best for you, you see.’

‘That’s what’s so infuriating! About you. About a hospital. About the world. Continual interference! Knowing what’s best for other people. I tried to kill myself. You know that, don’t you?’

She nodded.

‘Nobody’s business but mine whether I threw myself off a bloody cliff or not. I’d finished with life. I was down and out!’

She made a little clicking noise with her tongue. It indicated abstract sympathy. He was a patient. She was soothing him by letting him blow off steam.

‘Why shouldn’t I kill myself if I want to?’ he demanded.

She replied to that quite seriously.

‘Because it’s wrong.’

‘Why is it wrong?’

She looked at him doubtfully. She was not disturbed in her own belief, but she was much too inarticulate to explain her reaction.

‘Well—I mean—it’s wicked to kill yourself. You’ve got to go on living whether you like it or not.’

‘Why have you?’

‘Well, there are other people to consider, aren’t there?’

‘Not in my case. There’s not a soul in the world who’d be the worse for my passing on.’

‘Haven’t you got any relations? No mother or sisters or anything?’

‘No. I had a wife once but she left me—quite right too! She saw I was no good.’

‘But you’ve got friends, surely?’

‘No, I haven’t. I’m not a friendly sort of man. Look here, nurse, I’ll tell you something. I was a happy sort of chap once. Had a good job and a good-looking wife. There was a car accident. My boss was driving the car and I was in it. He wanted me to say he was driving under thirty at the time of the accident. He wasn’t. He was driving nearer fifty. Nobody was killed, nothing like that, he just wanted to be in the right for the insurance people. Well, I wouldn’t say what he wanted. It was a lie. I don’t tell lies.’

The nurse said:

‘Well, I think you were quite right. Quite right.’

‘You do, do you? That pigheadedness of mine cost me my job. My boss was sore. He saw to it that I didn’t get another. My wife got fed up seeing me mooch about unable to get anything to do. She went off with a man who had been my friend. He was doing well and going up in the world. I drifted along, going steadily down. I took to drinking a bit. That didn’t help me to hold down jobs. Finally I came down to hauling—strained my inside—the doctor told me I’d never be strong again. Well, there wasn’t much to live for then. Easiest way, and the cleanest way, was to go right out. My life was no good to myself or anyone else.’

The little nurse murmured:

‘You don’t know that.’

He laughed. He was better-tempered already. Her naïve obstinacy amused him.

‘My dear girl, what use am I to anybody?’

She said confusedly:

‘You don’t know. You may be—someday—’

‘Someday? There won’t be any someday. Next time I shall make sure.’

She shook her head decidedly.

‘Oh, no,’ she said. ‘You won’t kill yourself now.’

‘Why not?’

‘They never do.’

He stared at her. ‘They never do.’ He was one of a class of would-be suicides. Opening his mouth to protest energetically, his innate honesty suddenly stopped him.

Would he do it again? Did he really mean to do it?

He knew suddenly that he didn’t. For no reason. Perhaps the right reason was the one she had given out of her specialized knowledge. Suicides didn’t do it again.

All the more he felt determined to force an admission from her on the ethical side.

‘At any rate I’ve got a right to do what I like with my own life.’

‘No—no, you haven’t.’

‘But why not, my dear girl, why?’

She flushed. She said, her fingers playing with the little gold cross that hung round her neck:

‘You don’t understand. God may need you.’

He stared—taken aback. He did not want to upset her childlike faith. He said mockingly:

‘I suppose that one day I may stop a runaway horse and save a golden-haired child from death—eh? Is that it?’

She shook her head. She said with vehemence and trying to express what was so vivid in her mind and so halting on her tongue:

‘It may be just by being somewhere—not doing anything—just by being at a certain place at a certain time—oh, I can’t say what I mean, but you might just—just walk along a street some day and just by doing that accomplish something terribly important—perhaps even without knowing what it was.’

The red-haired little nurse came from the west coast of Scotland and some of her family had ‘the sight’.

Perhaps, dimly, she saw a picture of a man walking up a road on a night in September and thereby saving a human being from a terrible death …

February 14th

There was only one person in the room and the only sound to be heard was the scratching of that person’s pen as it traced line after line across the paper.

There was no one to read the words that were being traced. If there had been, they would hardly have believed their eyes. For what was being written was a clear, carefully detailed project for murder.

There are times when a body is conscious of a mind controlling it—when it bows obedient to that alien something that controls its actions. There are other times when a mind is conscious of owning and controlling a body and accomplishing its purpose by using that body.

The figure sitting writing was in the last-named state. It was a mind, a cool, controlled intelligence. This mind had only one thought and one purpose—the destruction of another human being. To the end that this purpose might be accomplished, the scheme was being worked out meticulously on paper. Every eventuality, every possibility was being taken into account. The thing had got to be absolutely fool-proof. The scheme, like all good schemes, was not absolutely cut and dried. There were certain alternative actions at certain points. Moreover, since the mind was intelligent, it realized that there must be intelligent provision left for the unforeseen. But the main lines were clear and had been closely tested. The time, the place, the method, the victim! …

The figure raised its head. With its hand, it picked up the sheets of paper and read them carefully through. Yes, the thing was crystal-clear.

Across the serious face a smile came. It was a smile that was not quite sane. The figure drew a deep breath.

As man was made in the image of his Maker, so there was now a terrible travesty of a creator’s joy.

Yes, everything planned—everyone’s reaction foretold and allowed for, the good and evil in everybody played upon and brought into harmony with one evil design.

There was one thing lacking still …

With a smile the writer traced a date—a date in September.

Then, with a laugh, the paper was torn in pieces and the pieces carried across the room and put into the heart of the glowing fire. There was no carelessness. Every single piece was consumed and destroyed. The plan was now only existent in the brain of its creator.

March 8th

Superintendent Battle was sitting at the breakfast table. His jaw was set in a truculent fashion and he was reading, slowly and carefully, a letter that his wife had just tearfully handed to him. There was no expression visible on his face, for his face never did register any expression. It had the aspect of a face carved out of wood. It was solid and durable and, in some way, impressive. Superintendent Battle had never suggested brilliance; he was, definitely, not a brilliant man, but he had some other quality, difficult to define, that was nevertheless forceful.

‘I can’t believe it,’ said Mrs Battle, sobbing. ‘Sylvia!’

Sylvia was the youngest of Superintendent and Mrs Battle’s five children. She was sixteen and at school near Maidstone.

The letter was from Miss Amphrey, headmistress of the school in question. It was a clear, kindly and extremely tactful letter. It set out, in black and white, that various small thefts had been puzzling the school authorities for some time, that the matter had at last been cleared up, that Sylvia Battle had confessed, and that Miss Amphrey would like to see Mr and Mrs Battle at the earliest opportunity ‘to discuss the position’.

Superintendent Battle folded up the letter, put it in his pocket, and said: ‘You leave this to me, Mary.’

He got up, walked round the table, patted her on the cheek and said, ‘Don’t worry, dear, it will be all right.’

He went from the room, leaving comfort and reassurance behind him.

That afternoon, in Miss Amphrey’s modern and individualistic drawing-room, Superintendent Battle sat very squarely on his chair, his large wooden hands on his knees, confronting Miss Amphrey and managing to look, far more than usual, every inch a policeman.

Miss Amphrey was a very successful headmistress. She had personality—a great deal of personality, she was enlightened and up to date, and she combined discipline with modern ideas of self-determination.

Her room was representative of the spirit of Meadway. Everything was of a cool oatmeal colour—there were big jars of daffodils and bowls of tulips and hyacinths. One or two good copies of the antique Greek, two pieces of advanced modern sculpture, two Italian primitives on the walls. In the midst of all this, Miss Amphrey herself, dressed in a deep shade of blue, with an eager face suggestive of a conscientious greyhound, and clear blue eyes looking serious through thick lenses.

‘The important thing,’ she was saying in her clear well-modulated voice, ‘is that this should be taken the right way. It is the girl herself we have to think of, Mr Battle. Sylvia herself! It is most important—most important, that her life should not be crippled in any way. She must not be made to assume a burden of guilt—blame must be very very sparingly meted out, if at all. We must arrive at the reason behind these quite trivial pilferings. A sense of inferiority, perhaps? She is not good at games, you know—an obscure wish to shine in a different sphere—the desire to assert her ego? We must be very very careful. That is why I wanted to see you alone first—to impress upon you to be very very careful with Sylvia. I repeat again, it’s very important to get at what is behind this.’