Полная версия

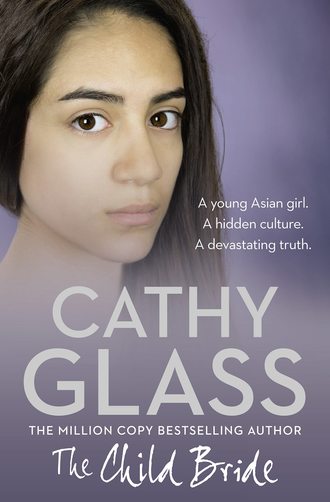

The Child Bride

‘No!’ Zeena cried again, shaking her head.

‘I’ll arrange for you to see my doctor then,’ I said quickly, for clearly this was causing Zeena a lot of distress. ‘There are two doctors in the practice I use, a man and a woman. They are both lovely people and good doctors.’

Zeena looked at me. ‘Are they white?’ she asked.

‘Yes. But I can arrange for you to see an Asian doctor if you prefer. There is another practice not far from here.’

‘No!’ Zeena cried again. ‘I can’t see an Asian doctor.’

‘All right, love,’ I said. ‘Don’t upset yourself. But can I ask you why you want a white doctor? Tara told me you asked for a white foster carer. Is there a reason?’ I was starting to wonder if this was a form of racism, in which case I would find Zeena’s views wholly unacceptable.

She was looking down and chewing her bottom lip as she struggled to find the right words. Tara was waiting for her reply too.

‘It’s difficult for you to understand,’ she began, glancing at me. ‘But the Asian network is huge. Families, friends and even distant cousins all know each other and they talk. They gossip and tell each other everything, even what they are not supposed to. There is little confidentiality in the Asian community. If I had an Asian social worker or carer my family would know where I was within an hour. I have brought shame on my family and my community. They hate me.’

Zeena’s eyes had filled and a tear now escaped and ran down her cheek. Tara passed her the box of tissues I kept on the coffee table, while I looked at her, stunned. The obvious question was: what had she done to bring so much shame on her family and community? I couldn’t imagine this polite, self-effacing child perpetrating any crime, let alone one so heinous that she’d brought shame on a whole community. But now wasn’t the time to ask. Zeena was upset and needed comforting. Tara was lightly rubbing her arm.

‘Don’t upset yourself,’ I said. ‘I’ll make an appointment for you to see my doctor.’

She nodded and wiped her eyes. ‘Thank you. I’m sorry to cause you so much trouble when you are being so kind to me, but can I ask you something?’

‘Yes, of course, love,’ I said.

‘Do you have any Asian friends from Bangladesh?’

‘I have some Asian friends,’ I said. ‘But I don’t think any of them are from Bangladesh.’

‘Please don’t tell your Asian friends I’m here,’ she said.

‘I won’t,’ I said, as Tara reached into her bag and took out a notepad and pen. However, it occurred to me that Zeena could still be seen with me or spotted entering or leaving my house, and I thought it might have been safer to place her with a foster carer right out of the area, unless she was overreacting, as teenagers can sometimes.

Tara was taking her concerns seriously. ‘Remember to keep your phone with you and charged up,’ she said to Zeena as she wrote. ‘Do you have your phone charger with you?’

‘Yes, it’s in my school bag in the hall,’ Zeena said.

‘Will you feel like going to school tomorrow?’ I now asked – given what had happened at school today I thought it was highly unlikely.

To my surprise Zeena said, ‘Yes. The only friends I have are at school. They’ll be worried about me.’

Tara looked at her anxiously ‘Are you sure you want to go back there?’ We can find you a new school.’

‘I want to see my friends.’

‘I’ll tell the school to expect you then,’ Tara said, making another note.

‘I’ll take and collect you in the car,’ I said.

‘It’s all right. I can use the bus,’ Zeena said. ‘They won’t hurt me in a public place. It would bring shame on them and the community.’

I wasn’t reassured, and neither was Tara.

‘I’d feel happier if you went in Cathy’s car,’ Tara said.

‘If I’m seen in her car they will tell my family the registration number and trace me to here.’

Whatever had happened to make this young girl so wary and fearful, I wondered.

‘Use the bus, then,’ Tara said, doubtfully. ‘But promise me you’ll phone if there’s a problem.’

Zeena nodded. ‘I promise.’

‘I’ll give you my mobile number,’ I said. ‘I’d like you to text me when you reach school.’

‘That’s a good idea,’ Tara said.

There was a small silence as Tara wrote, and I took the opportunity to ask: ‘Zeena, do you have any special dietary needs? What do you like to eat?’

‘I eat most things, but not pork,’ she said.

‘Is the meat I buy from our local butchers all right?’

‘Yes, that’s fine. I don’t eat much meat.’

‘Do you need a prayer mat?’ Tara now asked her.

Zeena gave a small shrug. ‘We didn’t pray much in my family, and I don’t think I have the right to pray now.’ Her eyes filled again.

‘I’m sure you have the right to pray,’ I said. ‘Nothing you’ve done is that bad.’

Zeena didn’t reply.

‘Can you think of anything else you may need here?’ Tara asked her.

‘When you visit my parents could you tell them I’m very sorry, and ask them if I can see my brothers and sisters, please?’

‘Yes, of course,’ Tara said. ‘Is there anything you want me to bring from home?’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘If you think of anything, phone me and I’ll try to get it when I visit,’ Tara said.

‘Thank you,’ Zeena said, and wiped her eyes. She appeared so vulnerable and sad, my heart went out to her.

Tara put away her notepad and pen and then gave Zeena a hug. ‘We’ll go and have a look at your room now before I leave.’

We stood and I led the way upstairs and into Zeena’s bedroom. It was usual practice for the social worker to see the child’s bedroom.

‘This is nice,’ Tara said, while Zeena looked around, clearly amazed.

‘Is this room just for me?’ she asked.

‘Yes. You have your own room here,’ I said

‘Do you share a bedroom at home?’ Tara asked her.

‘Yes.’ Her gaze went to the door. ‘Can I lock the door?’ she asked me.

‘We don’t have locks on any of the bedroom doors,’ I said. ‘But no one will come into your room. We always knock on each other’s bedroom doors if we want the person.’ Foster carers are advised not to fit locks on children’s bedroom doors in case they lock themselves in when they are upset. ‘You will be safe, I promise you,’ I added.

Zeena gave a small nod.

Tara was satisfied the room was suitable and we went downstairs and into the living room where Tara collected her bag.

‘Tell Cathy or phone me if you need anything or are worried,’ she said to Zeena. I could see she felt as protective of Zeena as I did.

‘I will,’ Zeena said.

‘Good girl. Take care, and try not to worry.’

Zeena gave a small, unconvincing nod and perched on the sofa while I went with Tara to the front door.

‘Keep a close eye on her,’ she said quietly to me so Zeena couldn’t hear. ‘I’m very worried about her.’

‘I will,’ I said. ‘She’s very frightened and anxious. I’ll phone you when I’ve made the doctor’s appointment.’

‘Thank you. I’ll be in touch.’

I closed the front door and returned to the living room where Zeena was on the sofa, bent slightly forward and staring at the floor. It was nearly five o’clock and Lucy would be home soon, so I thought I should warn Zeena so she wasn’t startled again when the front door opened.

‘You’ve met my daughter Paula,’ I said, sitting next to her. ‘Soon my other daughter, Lucy, will be home from work. Don’t worry if you hear a key in the front door; it will be her. Adrian won’t be home until about eight o’clock; he’s working a late shift today.’

‘Do all your children have front-door keys?’ Zeena asked, turning slightly to look at me.

‘Yes.’

‘I’m not allowed to have a key to my house,’ she said.

I nodded. Different families have different policies on this type of responsibility; however, by Zeena’s age most of the teenagers I knew had their own front-door key, as had my children.

‘What age will you have a key?’ I asked out of interest, and trying to make conversation to put her at ease.

‘Never,’ she said stoically. ‘The girls in my family don’t have keys to the house. The boys are given keys when they are old enough, but the girls have to wait until they are married. Then they may have a key to their husband’s house, if their husband wishes.’

Zeena had said this without criticism, having accepted her parents’ rules. I appreciated that hers was a different culture with slightly different customs. I had little background information on Zeena, so as she’d mentioned her siblings I thought I’d ask about them.

‘How many brothers and sisters do you have?’

‘Four,’ she said. ‘Two brothers and two sisters.’

‘How lovely. I think Tara told me they’re all younger than you?’

‘Yes, I am the eldest. The boys are aged ten and eight, and my sisters are five and three. They’ll miss me. I’m like a mother to them.’ Her eyes filled again and I gently touched her arm.

‘Tara said she’d speak to your parents about you seeing your brothers and sisters,’ I reassured her. ‘Do you have any photographs of them?’

‘Not with me; they’re at home.’

‘We could ask Tara to get some when she visits your parents?’ I suggested. I usually tried to obtain a few photographs of the child’s natural family, as it helped them to settle and also kept the bond going while they were separated. ‘Shall I phone Tara and ask her?’

‘I can text her,’ Zeena said.

She now drank some of her water and finally allowed her gaze to wander around the room and out through the patio windows to the garden beyond.

‘You have a nice home,’ she said, delicately holding the glass in her hands.

‘Thank you, love. I want you to feel at home here. I know it’s probably very different from your house, and our routines will be different too, so you must tell me if there is anything you need.’

‘Thank you,’ she said, and set her glass on the coffee table. ‘I expect I’ll have to ask you lots of questions,’ she added quietly.

‘That’s fine. Do you have any questions now?’

She looked at the clock on the mantelpiece. ‘Yes. What time would you like me to serve you dinner?’

Chapter Three

Good Influence

‘Serve dinner?’ I asked, thinking I’d misheard. ‘What do you mean?’

‘What time shall I make your evening meal?’ Zeena said, rephrasing the question.

‘You won’t make our evening meal,’ I said. ‘Do you mean you’d like to make your own?’ This seemed the most likely explanation.

‘No. I have to cook for you and your family,’ Zeena said.

‘Whatever gave you that idea?’ I asked.

‘I cook for my family at home,’ she said. ‘So I thought it would be the same here.’

‘No, love,’ I said. ‘I wouldn’t expect you or any child I looked after to cook for us. You can certainly help me, if you wish, and if there’s something I can’t make that you like, then tell me. I’ll buy the ingredients and we can cook it together.’

Zeena looked at me, bemused. ‘Do your daughters do the cooking?’ she asked.

‘Sometimes, but Lucy’s at work and Paula is at sixth form. They help at weekends. Adrian does too.’

‘But Adrian is a man,’ she said, surprised.

‘Yes, but there’s nothing wrong in men cooking. Many of the best chefs are men. How often do you cook at home?’

‘Every day,’ Zeena said.

‘The evening meal?’

‘Yes, and breakfast. At weekends I cook lunch too. In the evenings during the week I also make lunch for my youngest sister who doesn’t go to school, and my mother heats it up for her.’

While I respected that individual cultures did things in their own way and had different expectations of their children, this seemed a lot for a fourteen-year-old to do every day. ‘Does your mother go out to work?’ I asked, feeling this might be the explanation.

‘No!’ Zeena said, shocked. ‘My father wouldn’t allow her to go out to work. Sometimes she sews at home, but sometimes she is ill and has to stay in bed.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that,’ I said. ‘I hope she fully recovers soon.’

Zeena gave a small shrug. ‘She has headaches. They come and go.’

It didn’t sound as though her mother was very ill, and Zeena didn’t appear too worried about her. I was pleased she was talking to me. It was important we got to know each other. The more I knew about her, the more I should be able to help her.

‘Shall we take your case up to your room now?’ I suggested. ‘You’ll feel more settled once you’re unpacked and have your things around you.’

‘Yes. I’m sorry I’m such a burden. It’s kind of you to let me stay.’

‘You’re not a burden, far from it,’ I said, placing my hand lightly on her arm. ‘I foster children because I want to. We’re all happy to have you stay.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Positive.’

‘That’s very kind of you.’ She was so unassuming and grateful I was deeply touched.

We stood, but as we left the living room to go down the hall a key sounded in the front door. Zeena froze before she remembered. ‘Is that your other daughter?’

‘Yes, it’s Lucy. Come and say hello.’

We continued down the hall as Lucy let herself in.

‘This is Zeena,’ I said.

‘Hi, good to meet you,’ Lucy said easily, closing the door behind her. ‘How are you doing?’

‘I’m well, thank you,’ Zeena said politely. ‘How are you?’

‘Good.’

I kissed Lucy’s cheek as I always did when she returned home from work. ‘I’m taking Zeena’s case up to her room,’ I said. ‘Then I’ll start dinner.’

‘Is Paula back?’ Lucy asked, kicking off her shoes.

‘She’s in her room.’

‘Great! She’ll be pleased. I’ve got tickets for the concert!’

Lucy flew up the stairs excitedly, banged on Paula’s door and went in. ‘Guess what!’ we heard her shout. ‘The tickets are booked! We’re going!’ There were whoops of joy and squeals of delight from both girls.

‘They’re going to see a boy-band concert,’ I explained to Zeena.

She smiled politely.

‘They go a couple of times a year, when there is a group on they want to see. If you’re still here with us, you could go with them next time,’ I suggested.

‘My father won’t allow me to go to concerts,’ she said. ‘Some of my friends at school go, but I can’t.’

‘Maybe when you are older he’ll let you go,’ I said cheerfully, and picked up her case.

Zeena gave a small shrug but didn’t reply, and I led the way upstairs and into her room.

‘I’m pleased you’ve got some of your clothes with you,’ I said, positively. ‘I’ve plenty of spare towels and toiletries if you need them.’

‘Thank you.’

Zeena set the case on her bed, but then struggled to open the sliding lock. It wasn’t locked but the old metal fastener was corroded. I helped her and between us we succeeded in releasing the catch. She lifted the lid on the case and cried out in alarm. ‘Oh no! Mum has packed the wrong clothes.’ The colour drained from her face.

I looked into the open case. On top was what appeared to be a long red beaded skirt in a see-through chiffon material. As Zeena pushed this to one side and rummaged beneath, I saw some short belly tops in silky materials, glittering with sequins. I also saw other skirts and what looked like pantaloons, all similarly embroidered with sequins and beads, similar to the clothes Turkish belly-dancers wear. Zeena dug to the bottom of the case and then closed the lid.

‘What’s the matter?’ I asked. She was clearly upset.

‘Mum hasn’t packed my jeans or any of my ordinary clothes,’ she said, flustered and close to tears.

‘What are these clothes for, then?’ I asked, puzzled.

‘I don’t know,’ she replied. ‘They’re not mine.’

I looked at her, confused. ‘What do you wear when you’re not in your school uniform?’ I asked.

‘Jeans, leggings, T-shirts – normal stuff.’

‘I see,’ I said, no less confused but wanting to reassure Zeena. ‘Don’t worry, I keep spares. I can find you something to wear until we can get your own clothes from home. I guess your mother made a mistake.’

Zeena’s bottom lip trembled. ‘She did it on purpose,’ she said.

‘But why would your mother give you the wrong clothes on purpose?’ I asked.

Zeena shook her head. ‘I can’t explain.’

I’d no idea what was going on, but my first priority was to reassure Zeena. She was visibly shaking. ‘Don’t worry, love,’ I said. ‘I’ve got plenty of spares that will fit you. I can wash and dry your school uniform tonight and it will be ready for tomorrow.’

‘I can’t believe she’d do that!’ Zeena said, staring at the case.

Clearly there was more to this than her mother simply packing the wrong clothes, but I couldn’t guess what message was contained in those clothes, and Zeena wasn’t ready to talk about it now.

‘I’ll phone my mother and tell her I’ll go tomorrow and collect my proper clothes,’ Zeena said anxiously.

‘Do you think that’s wise?’ I asked, concerned. ‘Perhaps we should wait, and ask your social worker to speak to your mother?’

‘No. Mum won’t talk to her. My phone and charger are in my school bag in the hall. Is it all right if I get them?’

‘Yes, of course, love. You don’t have to ask.’

As Zeena went downstairs to fetch her school bag I went round the landing to my bedroom where I kept an ottoman full of freshly laundered and new clothes for emergencies. I knew I needed to tell Tara the problem with the clothes and that Zeena was going to see her mother. I would also note it in my fostering log. All foster carers keep a daily log of the child or children they are looking after. It includes appointments, the child’s health and well-being, significant events and any disclosures the child may make about their past. When the child leaves, this record is placed on file at the social services and can be looked at by the child when they are an adult.

I lifted the lid on the ottoman and looked in. Zeena was more like a twelve-year-old in stature, and I soon found a pair of leggings and a long shirt that would fit her to change into now, and a night shirt and new underwear. Closing the lid I returned to her room. She had moved her suitcase onto the floor and was now sitting on her bed with her phone plugged into the charger, and texting. In this, at least, she appeared quite comfortable.

‘I think these will fit,’ I said, placing the clothes on her bed. ‘Come down when you’re ready, love.’

‘Thank you,’ she said absently, concentrating on the text message.

I went into Paula’s room where she and Lucy were still excitedly discussing the boy-band concert, although it wasn’t for some months yet.

‘When you have a moment could you look in on Zeena, please?’ I asked them. ‘She’s feeling a bit lost at present. I’m going to make dinner.’

‘Sure will,’ Lucy said.

‘She seems nice,’ Paula said.

‘She is. Very nice,’ I said.

‘Don’t worry, we’ll look after her,’ Lucy added. Lucy had come to me as a foster child eight years before and therefore knew what if felt like to be in care. She was now my adopted daughter.

I left the girls and went downstairs. I was worried about Zeena and also very confused. I thought the clothes in the case were hers, although they seemed rather revealing and immodest, considering her father appeared to be so strict. But why had her mother sent them if Zeena couldn’t wear them? It didn’t make sense. Hopefully, in time, Zeena would be able to explain.

Downstairs in the kitchen I began the preparation of dinner. I was making a pasta and vegetable bake. Zeena had said she ate most foods but not a lot of meat. I’d found in the past with other children and young people I’d fostered that pasta was a safe bet to begin with.

After a while I heard footsteps on the stairs, and then Zeena appeared in the kitchen. She was dressed in the leggings and shirt and was carrying her school uniform.

‘They fit you well,’ I said, pleased.

‘Yes, thank you. Where shall I wash these?’ she asked.

‘Just put them in the washing machine,’ I said, nodding to the machine. ‘I’ll see to them.’

Zeena loaded her clothes into the machine and then began studying the dials. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘It’s different from the one we have at home. Can you show me how it works, please?’

‘Do you do the washing at home, then?’ I asked as I left what I was doing and went over.

‘Yes. My little brothers and sisters get very messy,’ Zeena said. ‘Mother likes them looking nice. I don’t mind the washing – we have a machine. I wish it ironed the clothes as well.’ For the first time since she’d arrived, a small smile flicked across her face.

I smiled too. ‘Agreed!’ I said as I tipped some powder into the dispenser, and set the dial. ‘Although many of our clothes are non-crease, and Lucy and Paula usually iron their own clothes.’

‘And your son?’ Zeena asked, looking at me. ‘He doesn’t iron his clothes, surely?’

‘Not yet,’ I said lightly. ‘But I’m working on it.’

Zeena smiled again. She was a beautiful child and when she smiled her whole face lit up and radiated warmth and serenity.

‘There’s a laundry basket in the bathroom,’ I said. ‘In future, you can put your clothes in that and I’ll do all our washing together.’

‘Thank you. I don’t want to be any trouble.’

‘You’re no trouble,’ I said.

Zeena hesitated as if about to add something, but then changed her mind. ‘I tried to phone my mother,’ she said a moment later. ‘But she didn’t answer. I’ll try again now.’

‘All right, love.’

She left the kitchen and I heard her go upstairs and into her bedroom. I finished preparing the pasta bake, put it into the oven and then laid the table. A short while later I heard movement upstairs and then the low hum of the girls’ voices as the three of them talked. I was pleased they were getting to know each other. I’d found in the past that often the child or young person I was fostering relaxed and got to know my children before they did me.

Presently I called them all down for dinner and they arrived together.

‘Zeena phoned her mum,’ Lucy said. ‘She’s going to collect her clothes tomorrow.’

‘And your mum was all right with you?’ I asked Zeena.

She gave a small nod but couldn’t meet my eyes, so I guessed her mother hadn’t been all right with her but she didn’t want to tell me.

‘Does she always speak in Bengali?’ Lucy asked, sitting at the table.

‘Yes,’ Zeena said.

‘Can she speak English?’ Paula asked, also sitting at the table.

‘A little,’ Zeena said. ‘But my father insists we speak Bengali in the house, so Mum doesn’t get much chance to practise her English.’

‘You’re very clever speaking two languages fluently,’ Paula said. ‘I struggled with French at school.’

‘It’s easy if you are brought up speaking two languages,’ Zeena said.

While Paula and Lucy had sat at the table ready for dinner, Zeena was still hovering. ‘Sit down, love,’ I called from the kitchen.

‘I should help you bring in the meal first,’ Zeena said.

Lucy and Paula looked at each other guiltily. ‘So should we,’ Lucy said.

‘It’s OK. The dish is very hot,’ I said. ‘You sit down, pet.’

Zeena sat beside Paula and opposite Lucy. Using the oven gloves I carried in the dish of pasta bake and set in on the pad in the centre of the table, next to the bowl of salad. I returned to the kitchen for the crusty French bread, which I’d warmed in the oven, and set that on the table too.

‘Mmm, yummy,’ Paula said, while Lucy began serving herself.

‘It’s just pasta, vegetables and cheese,’ I said to Zeena. ‘Help yourself. I hope you like it.’

‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘I’m sure I will.’

When a child first arrives, mealtimes can be awkward for them. Having to sit close to people they don’t know and eat can be quite intimidating, although I do all I can to make them feel at ease. Some children who’ve never had proper mealtimes at home may have never sat at a dining table or used cutlery, so it’s a whole new learning experience for them. However, this wasn’t true of Zeena. As we ate I could see that Lucy and Paula were as impressed as I was by her table manners. She sat upright at the table and ate slowly and delicately, chewing every mouthful, and never spoke and ate at the same time. Every so often she would delicately dab her lips with her napkin. All her movements were so smooth and graceful they reminded me of a beautiful swan in flight or a ballet dancer.