Полная версия

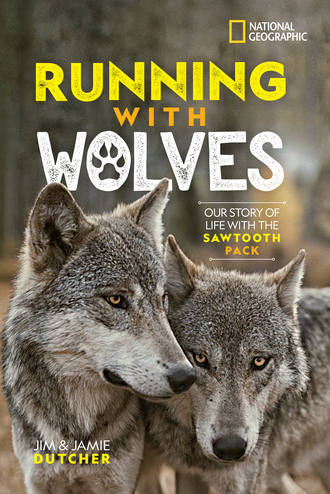

Running with Wolves

We found the den amid a sheltered rocky outcrop. The kittens were just minutes old. Their spotted fur blended in with the ground, offering some protection against other predators. The helpless kittens’ eyes were closed and their little ears lay flat against their head. The newborns would remain blind and completely dependent on their mother for 10 days.

One by one, she gently picked them up by the scruff of their neck in her jaws and laid them in a soft bed of pine needles. Then she cleaned them with her large, rough tongue. When a kitten cried out with a squeaky rahr, rahr, the mother gave a few more reassuring licks.

These were the intimate sights and sounds I most wanted to capture, like the mother nursing her kittens—a tender moment perhaps never seen with cougars in the wild. There were many such moments of peace and tranquility between parent and young. There were other moments of high-energy training between teacher and student.

For instance, one day I watched with keen interest as a kitten tugged at one of his mother’s ears while she lay on the ground. Playing along, she gently laid a massive paw on his head like she was petting him. Then he saw her tail—a long rope of fur waving lazily in the air. It was like the tail was daring the kitten to grab it. The kitten took his chance and pounced. He bit and pawed at the tail for a few seconds, until his mother decided enough was enough and brushed him aside.

Every moment of play was actually a valuable lesson. The growing kittens were learning how to stalk and take down prey by sneaking up on each other and play fighting. These bouts were like friendly wrestling matches, but with teeth.

By autumn, the kittens were learning to hunt real prey, from mice in the fields to ducks on the pond. They were becoming increasingly wild, too.

They hid from me more often, and hissed when I approached. I was glad. One day they would be released into the wilderness, and I didn’t want them to get too comfortable with people. I didn’t want them to get used to having a harmless camera pointed at them, either. Hunting cougars is legal in many western states, and the next piece of equipment that was pointed at them might be a rifle.

When I started the cougar project, there was no guarantee of success. A lot could’ve gone wrong. The mother might never have accepted me, or the crew, into her world. She may have chosen to hide her young from the watchful eye of my camera lens. Or she may have turned aggressive, making the project too dangerous to continue.

Fortunately, none of these things happened. We were able to show the cougar not only as a powerful hunter but also as a nurturing parent and a patient teacher. We even revealed the sounds of the cougars’ world—from the chirps, purrs, mews, and growls of their language to the shoulder-shivering scrapes of the sharpening of the mother’s claws against a tree trunk.

The following spring, the young cougars reached the age when they normally go their separate ways. They were ready.

The mother was too familiar with humans to survive in the wilderness, so she was taken to a large preserve to live out her days in safety. The young cougars had a less predictable but more natural future.

We flew them by helicopter to a remote area of Idaho. Thanks to instinct and lessons learned as kittens, they were now self-sufficient and able to live a truly wild life. They stepped from their crates and never looked back. In a few days, the brothers would head in different directions to establish their own territories. They were free.

My cougar adventure was over, but theirs were just beginning.

What next? That’s what I asked myself as we removed the fencing and any trace of human activity at the cougar enclosure.

I was itching to start another project. As before, I wanted to do something that would inspire people to care about wildlife. The best way I knew how to do that was to make another film about the hidden daily life of an animal. It would have to be an animal that was largely misunderstood, an animal that was rarely filmed in the wild.

But, which animal?

To help me decide, I thought a little vacation was in order. Not Disney World or a Caribbean cruise. No, I needed a sense of peace—the kind of peace I get from a place of quiet natural beauty, a place where I could clear my mind. I decided to return to the Wyoming ranch in the Absarokas.

More than 30 years after I had spent the summer as a wrangler, I returned as a guest. For company, I had a stack of books about animals. I was going to pore over them for a few weeks in between hiking and fishing. Somewhere in the research and the inspiration of the mountains, I figured I’d find the subject of my next film.

I didn’t know the answer would hit me like a lightning bolt.

On the second day of the trip, I received a phone message that my cougar film, called Cougar: Ghost of the Rockies, had been chosen as the first episode of a nature TV series. I was overjoyed. I felt like a 16-year-old again, full of boundless energy.

I had the irresistible urge to make a climb that had been one of my favorites as a teen. I remembered that the view at the top was spectacular. I stepped my way through a stand of white pines to the base of a hill. I scrambled up the rocky slope, hunched over to keep my balance. At the top, I stood up straight to take in the view. Suddenly, I froze like a statue.

On the alpine meadow below me stood a gray wolf.

In a flash, my mind raced back to that day 30 years earlier when I had seen my first wolf. Now, in the same area, I was looking at my second. Could this be a descendant? I wondered about the possibility as I raised my binoculars to get a closer look. That’s when he saw me. Unlike the wolf that stared me down years before, this one was skittish and ran away at the sight of me.

In that brief moment, I knew that I had found the subject of my next film. I still didn’t know much about wolves, but I was about to begin a journey that would make me an expert in ways I never thought possible.

The first step in that journey was to separate fact from fiction. And when it comes to wolves, I learned that there was very little fact and a whole bunch of fiction.

Like most people, much of what I knew—or thought I knew—about wolves was based on the sayings, songs, movies, and fairy tales I had learned since childhood. A “wolf in sheep’s clothing” is someone whose pleasant personality hides sinister motives. In the fairy tale “Little Red Riding Hood,” a wolf devours a grandmother and tries to trick her granddaughter into a similar fate.

Horror movies about werewolves—bloodthirsty half-man, half-wolf creatures—have been popular for generations. And who is trying to blow down the houses of the Three Little Pigs and eat the occupants? The Big Bad Wolf, of course!

Such stories and sayings show the wolf as a tricky, ferocious, evil creature—one to be feared, hated, and destroyed. Among those who held such perceptions were ranchers, as well as farmers who raised livestock. If a cow or sheep went missing, wolves were usually blamed.

Not that it never happened. These predators sometimes did kill a member of a herd, but the culprit was much more likely to be disease, weather, injury, or a predator other then a wolf, including domestic dogs.

I wasn’t completely surprised to learn how make-believe stories fed people’s misconceptions about wolves. But I was astounded and alarmed to learn how false perceptions had affected the wolf population. From the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s, about two million wolves had been killed in the United States, largely because they were seen as a threat to livestock. In fact, in 1915, the U.S. government hired hunters and called for the extermination of wolves.

It almost happened.

The government paid hunters for each wolf they killed. By the time I started to research my wolf film, this beautiful animal that once inhabited forests and plains from Maine to California existed only in small pockets of the United States. At the most, no more than a handful of wolves roamed the entire American West. Even though they were protected under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, their numbers were still dangerously low.

More importantly, attitudes about wolves had changed little, especially among the ranchers and big-game hunters who shared the environment with this animal. It was personally disheartening. These were my neighbors and friends, yet our views of wolves were very different. Many people still considered them to be aggressive killers. But the more research I uncovered, the more I saw wolves as curious, intelligent, and even shy. I knew they were getting a bad rap.

I couldn’t really blame people for their attitudes, though. Myths die hard, especially in the absence of truth.

In 1990, we knew surprisingly little about the nature of wolves. We had measurable facts—things that you could attach a number to—like a wolf’s size, how far it roams, how long it lives, things like that.

We knew wolves live in packs, but we had little idea about how they live. We knew almost nothing about the secret, hidden lives of wolves. I needed to change that. I needed to show people a side of wolves they never saw, never even knew existed. Perhaps that information would help replace myth with truth.

I felt the only way to discover that truth was to live with wolves.

So, I decided to assemble a wolf pack to observe and film within the world’s largest wolf enclosure. I had no idea what I was getting into and how difficult the road ahead would be, but I knew that I was doing the right thing. I was certain that if only someone would take the time to listen, the wolf would tell its story. I was willing to listen.

So was a certain zookeeper in Washington, D.C.

Jamie and I had kept in touch ever since we met on a trip home from Africa three years earlier. She was as excited as I was when I told her about my plans to live with wolves. We both knew this was a much more ambitious undertaking than the cougar project, and she understood why I had to do it.

In the early days of the project—before Jamie joined me in Idaho—I depended on her advice and support through letters and conversations. I still remember the joy I felt as I wrote her with some thrilling news.

“I found it!”

That was my message in a nutshell.

In a letter to Jamie, I described how I had found the perfect place to build wolf camp. It was in the Sawtooth Mountains, across the valley from where cougar camp had been.

I had explored other mountain ranges in central Idaho, but I could never find a place that had everything the wolves would need. Then I discovered Meadow Creek. It’s an area of meadows, forests, creeks, marshes, and ponds, all near the base of the Sawtooth Mountains.

This place was really off the beaten path. I took a dirt road across two ranches, and when the road ended, I got out and walked. The landscape changed dramatically as I hiked up a slight incline. It’s amazing the difference a little change in elevation makes! Instead of the dry sage of the ranches, I suddenly found myself in a green, grassy meadow.

It was like a piece of paradise. A mountain brook trickled past me on my left while bright yellow aspen leaves twisted and turned in the breeze on my right. In front of me stood a deep green forest of towering lodgepole pine, Douglas fir, and spruce. And above that rose the majestic Sawtooths. Their summits formed a jagged gray ridge against the deep blue sky.

Meadow Creek had everything I could want. It was remote enough that people wouldn’t wander by and disturb the wolves. In fact, people would have a hard time finding this place even if they were looking for it. Yet the site could be reached by an equipment truck, which would be needed to haul in materials to build the enclosure.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.