Полная версия

Rosie’s War

‘She’s hungry,’ John said, affronted by his daughter’s telling off.

Rosie made to get up, then sank back down to the mattress again. ‘Kitchen’s blown to smithereens. Won’t find the bottles or the milk powder; won’t be able to wash her either, if the water’s off.’ She began unbuttoning her bodice. ‘I’ll feed her,’ she said. Turning a shoulder to her father so as not to embarrass him, she helped the child to latch onto a nipple. Her breasts were rock hard with milk, hot and swollen, but she put up with the discomfort, biting her lip against the pain. She encouraged the baby to feed with tiny caresses until finally she stopped suckling and seemed to fall asleep with a sated sigh.

‘What you gonna call her?’ John whispered. He had rolled over onto his side, away from mother and child to give them some privacy. His voice sounded different: high-pitched with pain still, but there was an underlying satisfaction in his tone.

Rosie smiled to herself, wondering how her father knew she’d been thinking about names for her daughter. ‘Hope …’ she said on a hysterical giggle. ‘Seems right … so that’s what I’m choosing. Hope this bloody war ends soon … hope we get a place to live … hope … hope … hope …’

‘Hope the doctors sort me bloody leg out for us, I know that.’ John joined in gruffly with the joke.

‘You’ll be right as rain with a peg leg … Long John Silver,’ Rosie teased.

They both chuckled although John’s laughter ended in a groan and he shifted position to ease his damaged limb.

In her mind Rosie knew she’d chosen her daughter’s name for a different reason entirely from those she’d given. Her greatest hope was that her daughter would forgive her if she ever discovered that she’d abandoned her like that. The poor little mite could have suffocated to death if she’d not been uncovered in time. Or the weight of the shattered window frame on top of the pram might even-tually have crushed the hood and her daughter’s delicate skull. The idea that Hope might have suffered a painful death made bile rise in Rosie’s throat. She closed her eyes and forced her thoughts to her other hope.

She hoped that Nurse Johnson would forgive her. The woman desperately wanted to be a mother, and Rosie had promised her that her dream would be real. Rosie sank back on the mattress beside Hope and curved a protective arm over her daughter as she slept, a trace of milk circling her mouth.

But Rosie had no intention of allowing anybody to take her Hope away now. She’d do anything to keep her.

‘Hear that Dad?’

‘What … love?’ John’s voice was barely audible.

‘Bells … ambulance or fire engine is on its way. You’ll be in hospital soon,’ she promised him. While she’d been cuddling her little girl she’d heard her father’s groans although he’d been attempting to muffle the distressing sounds.

‘Ain’t going to hospital; they can patch me up here,’ he wheezed.

‘Don’t be daft!’ Rosie said but there was a levity in her tone that had been absent before. She couldn’t be sure which of the services was racing to their aid and she didn’t care. She was simply glad that somebody might turn up and know what to do if her father passed out from the pain that was making him gasp, because she hadn’t got a clue.

‘Anybody home?’

The shouted greeting sounded cheery and Rosie jumped up, clutching Hope to her chest. This time she emerged carefully into their wrecked hallway rather than plunging out as she had when in a mad scramble to rescue her daughter. A uniformed woman of about Doris’s age was picking her way over the rubble in Rosie’s direction.

‘Well, you look right as ninepence,’ the auxiliary said with a grin. ‘So does the little ’un.’ The woman nodded at Hope, now asleep in Rosie’s arms. ‘Can’t say the same for the house though, looks like a bomb’s hit it.’ She snorted a chuckle.

Rosie found herself joining in, quite hysterically for a few seconds. ‘Dad’s in the cellar … broken leg. He caught the blast in the back garden.’

‘Righto … let’s take a shufti.’ The woman’s attitude had changed to one of brisk efficiency and she quickened her pace over the rubble.

Even when she heard her father protesting about being manhandled, Rosie left them to it downstairs. She had instinctively liked the ambulance auxiliary and she trusted the woman to know what she was doing. A moment later when she heard her father grunt an approximation of one of his chuckles Rosie relaxed, knowing the auxiliary had managed to find a joke to amuse him too. Stepping carefully over debris towards the splintered doorway she stopped short, not wanting to abandon her father completely by going outside even though the all clear was droning. She found a sound piece of wall and leaned back on it, rocking side to side, eyes closed and crooning a lullaby to Hope, who slept contentedly on, undisturbed by the pandemonium in the street.

CHAPTER FOUR

‘My, oh my, look how she’s grown. Only seems like yesterday little Hope was born.’ Peg Price stepped away from the knot of women congregated by the kerb. They were all wearing a uniform of crossover apron in floral print with their hair bundled inside scarves knotted atop their heads. Peg ruffled the child’s flaxen curls. ‘She’ll be on her feet soon, won’t she, love?’

To a casual observer the meeting might have seemed friendly, but Rosie knew differently and wasn’t having any of it. She attempted to barge past the weedy-looking woman blocking her way. But Peg Price was no pushover and stood her ground.

‘Some of ’em are late starters,’ another woman chipped in, eyeing the toddler sitting in her pram. ‘Don’t you worry, gel, kids do everything in their own sweet time.’

‘I’m not worried about a thing, thanks.’ Rosie gave a grim smile, attempting to manoeuvre around the trio of neighbours stationed in front of her. They were all aware that her daughter was walking because they spied over the fences and watched Hope playing in the back garden.

Even after two years the local gossips hadn’t given up on probing for a bit of muck to rake over. Rosie knew what really irked them was that she had so far managed to remain unbowed by their malice. She’d never crept about, embarrassed. She’d brazened out their snide remarks about her daughter’s birth. And her father and Doris had done likewise.

After the Gardiners’ home had been destroyed at the bottom end of the street the council had rehoused them in the same road, so they were still neighbours with the Price family.

‘Coming up to her second birthday, by my reckoning.’ Peg stepped into the road to foil Rosie’s next attempt to evade her.

‘She’s turned two.’ Rosie glared into a pair of spiteful eyes.

‘Shame about yer ’usband, ain’t it? Proud as punch, he’d be, of that little gel.’ May Reed chucked the child under her rosy chin. ‘’Course, she’ll ask about her daddy, so you’ll be ready with some answers for the kid, eh, love?’

‘Yeah, I’ve already thought of that, thanks all the same for your concern.’ Rosie’s sarcasm breezed over her shoulder as she moved on, ignoring May’s yelp as the pram clouted her hip.

‘Looks like you, don’t she, Rosie? Just as well, ain’t it?’

It wasn’t the sly comment but Peg Price’s tittering that brought Rosie swinging about. ‘Yeah, she’s just like me: blonde and pretty. Lucky, aren’t I, to have a daughter like that? Jealous?’ Rosie’s jaunty taunt floated in her wake as she marched on.

It wasn’t in Rosie’s nature to be vindictive, but she was happy to give as good as she got where those three old cows were concerned. Over two years Peg and her cronies had done their best to browbeat her into admitting her baby was a bastard and she was ashamed of Hope. But she’d never been ashamed of Hope, even in those early days when she’d considered giving her away.

Everybody knew how to shut Peg Price up: rub the woman’s nose in the fact that her only child was an ugly brat. If anybody was ashamed of their own flesh and blood it was Peg. Not only was Irene a spotty, sullen teenager, she had a reputation for chasing after boys.

‘Conceited bleedin’ madam, ain’t yer?’ Peg had caught up with Rosie and grabbed her arm. All pretence at geniality had vanished.

‘Well, that’s ’cos I’ve got something to be conceited about.’ Rosie wrenched herself free of the woman’s chapped fingers. ‘Bet you wish your Irene could say the same, don’t you?’

‘What d’yer mean by that?’ Peg snarled, shoving her cardigan sleeves up to her elbows in a threatening way. ‘Come on, spit it out, so I can ram it back down yer throat.’

Rosie gave her a quizzical look. Peg’s pals were enjoying the idea of a fight starting. May Reed had poked her tongue into the side of her cheek, her eyes alight with amusement as she waited expectantly for the first punch to be thrown.

‘You don’t want to let the likes of her talk to you like that, Peg.’ May prodded her friend’s shoulder when a tense silence lengthened and it seemed hostilities might flounder.

‘At least your Irene’s decent, unlike some I could mention.’ Lou Rawlings snorted her two penn’orth. ‘Widow, my eye! I reckon that’s a bleedin’ brass curtain ring.’ She pointed a grimy fingernail at Rosie’s hand, resting on the pram handle.

‘Decent, is she, your Irene?’ Rosie echoed, feigning surprise and ostentatiously twisting her late mother’s thin gold band on her finger. ‘Go ask Bobby West about that then …’cos I heard different, just yesterday.’

Rosie carried on up the road with abuse hurled after her. She already felt bad about opening her mouth and repeating what Doris had told her. Peg’s daughter had been spotted behind the hut in the local rec with Bobby West.

Although they’d lived close for many years the gap in their ages meant Rosie and Irene had never been friends. Previously they’d just exchanged a hello or a casual wave; once Irene found out who’d dropped her in it Rosie reckoned she’d get ignored … or thumped by Irene. In a way she felt sorry for Peg’s daughter. The poor girl had every reason to stomp about with her chops on her boots with that old dragon for a mother.

Lost in thought, Rosie almost walked straight past her house. They’d been rehoused for ages but the Dorniers had kept coming although their street had so far avoided further damage. She still headed automatically to her childhood home, further along. She found it upsetting to see the place in ruins so usually took a detour to avoid the bomb site it now was. She unlatched the wooden gate, fumbling in her handbag for her street door key. Glancing over a shoulder, Rosie noticed that trouble was on its way: Peg was marching in her direction with fat Lou and May flanking her. The unholy trinity, as her father called the local harridans, looked about to attack again before Rosie could make good her escape.

Rosie stuck her bag back under the cover of the pram then wheeled it about and set off along the road again. She was feeling so infuriated that, outnumbered or not, she felt she might just give Peg Price the scrap she was spoiling for. She wasn’t running scared of them; but Rosie was keen to avoid upsetting her little girl.

Hope was sensitive to raised voices and a bad atmosphere. Just yesterday her daughter had whimpered when Rosie had given Doris a mouthful. Rosie didn’t mind helping out with all the household chores, but she was damned if she was going to act as an unpaid skivvy for her new stepmother.

Since she’d moved in as Mrs Gardiner, Doris had made it clear she thought her husband’s daughter had outstayed her welcome and she’d only tolerate Rosie’s presence if she gained some benefit from it.

Rosie didn’t see herself as a rival for John’s affections, but Doris seemed to resent her nevertheless. Naturally, her father’s second wife wanted to be the most important person in her husband’s life. Unfortunately, John still acted as though his daughter and granddaughter had first claim on him. John and Doris weren’t exactly newlyweds, having got married six months ago, but Rosie thought that the couple were entitled to some privacy.

‘And so do I want some bloody privacy,’ she muttered to herself now. She dearly wished to be able to afford a room for herself and Hope, but the cheapest furnished room she’d found was ten shillings a week, too dear for her pocket. So for now, they’d all have to try to muddle along as best they could. On fine days like today Rosie often walked for miles because the balmy June air was far nicer than the icy atmosphere she was likely to encounter indoors.

Now that her daughter was potty-trained Rosie felt ready to find Hope a place at a day nursery so she could get a job. Her father had never fully recovered his fitness after they’d been bombed out and Rosie wasn’t sure he was up to the job of caring for a lively toddler, although he’d offered. Rosie didn’t want to be beholden to her stepmother. Doris had a job serving in a bakery and was always complaining about feeling tired after being on her feet all day.

Rosie turned the corner towards Holborn, tilting her face up to the sun’s golden warmth. It was late afternoon, but at this time of the year the heat and light lingered well into the evening. If John had prepared her tea he’d put the meal on the warming shelf for her to eat on her return.

‘Hey … is that you, Rosie Gardiner? Is it really you?’

Rosie was idly window-shopping by Gamages department store when she heard her name called. Pivoting about, she frowned at a brunette hurrying towards her bouncing a pram in front of her. She didn’t recognise the woman, and assumed she’d been spotted by a forgotten face from schooldays.

‘Don’t remember me, do you? Bleedin’ hell, Rosie! It’s only been a few years!’ The newcomer grinned, wobbling Rosie’s arm to jolt an answer from her. ‘I can’t have changed that much.’

It was the young woman’s rough dialect and unforgettably infectious smile that provided a clue. The poor soul had changed; in a short space of time her acquaintance from the Windmill Theatre looked as though she’d aged ten years. If Rosie had relied on looks alone to jog her memory, she’d never have identified her. ‘Oh … of course I remember you. It’s Gertie … Gertie Grimes, isn’t it?’

Gertie nodded, still smiling. Then she gave a grimace. ‘It’s all right, nobody from the old days recognises me. Look a state, don’t I?’ She sighed in resignation.

‘No …’ Rosie blurted, then bit her lip. There was no point in lying. Gertie Grimes was nobody’s fool, Rosie remembered, and wouldn’t appreciate being treated as one. ‘Been a bloody long war, Gertie, hasn’t it?’ she said sympathetically.

‘Oh, yeah …’ Gertie drawled wearily. ‘And it ain’t done yet.’

‘There’s an end in sight, though, now the troops have landed in Normandy.’ Rosie gave the woman’s arm a rub, sensing much had happened in Gertie’s life since they’d last spoken to make her sound so bitter.

‘Perhaps we’ll be having a victory knees-up soon.’ Gertie brightened. ‘Come on, tell me all about it.’ She nodded at the little girl spinning the beads threaded on elastic strung between the pram hood fixings. ‘Beauty, she is; what’s her name?’ Gertie lifted Rosie’s hand and saw the wedding ring. ‘I suppose you married an army general to make me really jealous. I remember the top brass were always fighting over you at the Windmill. Could’ve had yer pick, couldn’t you; all the girls envied you.’

‘I was a bit of a show-off, wasn’t I?’ Rosie replied with a rueful smile. ‘Her name’s Hope; but you go first. I remember you had boys, but this isn’t a boy.’ Rosie tickled the cheek of the little girl with dark brown hair and her mother’s eyes. The child looked to be a few months older than Hope and the two little girls were now leaning towards each other sideways, giggling, to clasp hands.

‘Never got a chance to tell you I was pregnant, did I, ’cos I left soon as I found out?’ It was a fib; Gertie had concealed her pregnancy for quite some time from everyone at work, and from her cuckolded husband. ‘She’s called Victoria and she’s gone two and a half now.’

‘Crikey, you’ve got your hands full, Gertie. I know you’ve got four sons, so a girl must’ve been a lovely surprise for you and your husband.’

Gertie frowned into the distance. None of what Rosie assumed was true. Gertie now had just two children alive and, far from being delighted about another baby, her husband had knocked her out cold when he found out he’d not fathered the child she was carrying. ‘Got just the one boy now. Three of them was lost in a raid during the Blitz. Direct hit … happened before Vicky was born.’

‘Oh … I’m so sorry,’ Rosie gasped. The memory of almost losing Hope when their house was destroyed still tormented her. Her remorse over that day was a constant companion and she could see in Gertie’s eyes that the woman was battling similar demons.

‘Don’t blame yourself,’ Rosie said softly. ‘I can’t know how you feel, not really, so I won’t say I do. But I nearly lost Hope so I know what it is to feel guilty.’ She paused. ‘She was nearly crushed to death in her pram on the day we got bombed out in Shoreditch. It was my fault, no getting away from it.’ Rosie cleared the huskiness from her voice with a small cough. ‘My dad had been injured in the back garden, you see, and I was so concerned about getting him indoors that I forgot all about my baby in the front room.’ It was the first time Rosie had admitted to anybody what she’d done. Not even Doris knew what had occurred that terrible afternoon.

‘I still wake up at nights howling about the night my boys were killed. I feel so ashamed,’ Gertie croaked. ‘Least you was close enough to put things right before it was too late.’ She sunk her chin to her chest. ‘I wasn’t there for them … nor was me husband … or me eldest boy. All out, we was, and Simon and Adam and Harry perished all alone in the house. Harry was just about the age Vicky is now. But it’s the other two that I ache most for. Being older, they might’ve understood and been so frightened, the poor little loves.’ Gertie swiped the heel of a hand over her cheeks. ‘Please God they didn’t suffer too much.’

Rosie put an arm about Gertie’s shoulders and hugged her tight. ‘They’re at peace now, Gertie,’ she soothed. ‘You’ve done it so far, you can carry on a bit longer … then a bit longer after that. That’s what I told myself, when I felt like beating my head against the wall to punish myself.’

‘The ambulance girls … they fought like demons to keep my Harry alive. He was protected a bit by being in his pram, you see.’ Gertie gulped back the lump in her throat. ‘But they couldn’t save him. One of the poor lasses was bawling almost as loud as me when they put the three bodies in the back of the ambulance.’

‘Oh, Gertie, I’m so sorry …’

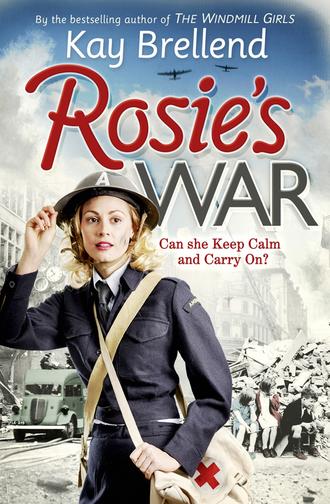

Gertie sniffed and blew her nose. ‘Wanted to join the ambulance auxiliaries after that. Rufus wouldn’t hear of it. But I went along for the interview anyhow.’ Gertie looked crestfallen. ‘Didn’t pass the test, though. Best if you’ve got no young kids, they said, ’cos of the dangerous nature of the job.’ Gertie grimaced. ‘I told ’em about the dangerous nature of living in the East End. Didn’t go down too well with the snooty cows.’

Rosie was impressed that Gertie had tried to join the auxiliaries. It seemed such a fitting thing to do in the circumstances. She remembered how efficiently the ambulance teams had got on with things when they’d been bombed out at home. At the time Rosie had been wrapped up in caring for her daughter and had happily allowed the auxiliaries to take over tending to her father. The middle-aged woman who’d patched him up, along with a younger female colleague, had almost carried him up the cellar stairs. Though the two of them looked like butter wouldn’t melt, they’d come out with a few risqué jokes to distract John while loading him into the back of a makeshift ambulance.

With bad grace Doris had offered Rosie and Hope a roof over their heads with her in Hackney until John came out of hospital and the Council re-housed them. None of the trouble they’d suffered though could compare with Gertie’s suffering.

‘What’s your oldest lad’s name?’ Rosie asked ‘Bet he’s quite the young man now, isn’t he?’

‘Oh, Joey’s cock of the walk, all right. Thirteen, he is, and giving me plenty of lip.’ Gertie managed a tiny smile. ‘Mind you, that one always did have too much to say for himself. Gets that off his dad.’

‘I bet your husband dotes on his princess.’ Rosie nodded at Victoria. ‘My dad calls Hope his princess.’ She gave her friend a smile. ‘Best be getting off, I suppose … be late for tea. Dad’ll wonder where we are.’ Rosie regretted drawing attention to her own circumstances; Gertie would wonder why she was referring to her father so much rather than to a husband.

‘Fine reunion this has turned out to be,’ Gertie’s mumble held a hint of wry humour.

‘Glad I bumped into you, Gertie,’ Rosie said, glancing at her daughter, clapping hands with Victoria.

‘Shall we meet up again?’ Gertie looked at Rosie quite shyly as though anticipating a rebuff. ‘The little ’uns seem to be getting along. We could take them for a stroll round a park another day. Perhaps have a picnic … if you like.’

‘I’d like that very much,’ Rosie said enthusiastically. ‘We can reminisce about old times. What a to-do that was about Olive Roberts. Who’d have thought it?’

‘Never liked that woman,’ Gertie’s eyes narrowed as she reflected on the kiosk attendant at the Windmill Theatre who’d been unmasked as a dangerous Nazi sympathiser.

‘Quite hair-raising, wasn’t it?’ A gleam of nostalgia lit Rosie’s eyes. ‘We saw some times there, didn’t we? Good and bad.’

Gertie grunted agreement. ‘I miss the old place,’ she said. ‘Funny thing is, when I was at work, I couldn’t wait to finish a shift and get home to me boys, though they drove me up the wall. Now I’m home all the time I wish I’d got a job.’

‘Now Hope’s turned two I’m after a nursery place for her so I can get back to work.’ Rosie tidied her daughter’s fair hair with her fingers. ‘I want to help bring this damned war to an end.’

‘Not going back on stage?’ Gertie asked.

‘No fear.’

‘Before you disappear, you must tell me about your other half.’ Gertie teasingly prodded Rosie’s arm.

‘Tell you more when I see you next week,’ Rosie replied, turning the pram about, ready to head back towards Shoreditch. ‘How about Thursday afternoon at about three o’clock? We could meet right here outside Gamages …’

‘Suits me; Rufus goes to a neighbour’s to play cards on Thursdays.’

‘Your husband back on leave, is he?’ Rosie asked.

‘Oh …’course, you wouldn’t know that either. He’s been invalided home from the army,’ Gertie said briskly to conceal the wobble in her voice.

Rosie read from Gertie’s fierce expression that the woman felt she’d suffered enough condolences for one day. ‘See you Thursday then.’ Rosie let off the brake on the pram.

The two women headed off in opposite directions, then both turned at the same time to wave before settling into their strides.

Rosie walked quickly, aware her dad would be wondering where she’d got to, but at the back of her mind was the conversation she’d had with Gertie about the ambulance auxiliaries. Rosie wanted to do a job that was vital to the war effort and in her book there was nothing more important than saving lives. So she reckoned she knew what employment she’d apply for. All she had to do was break it to her dad that she was going to volunteer for a position with the ambulance auxiliaries.

CHAPTER FIVE

‘Long time no see, mate.’

John Gardiner almost dropped the mug of tea he’d been cradling in his palm. He’d opened the front door while carrying it, expecting to see his daughter on the step. He’d been about to say, ‘What, forgot your key again, dear?’ because Rosie had earlier in the week knocked him up when he’d been snoozing on the settee.

Instead his welcoming smile vanished and he half closed the door in the wonky-eyed fellow’s face. It’d been a year since he’d caught sight of Frank Purves, and then they’d only nodded at one another from opposite pavements. On that occasion John had been tempted to hare across the road to throttle the man for having spawned a fiend. But, of course, he hadn’t because that would have given the game away. And John would sooner die than cause his daughter any more trouble. He kept his welcome to a snarled, ‘What the hell d’you want?’