Полная версия

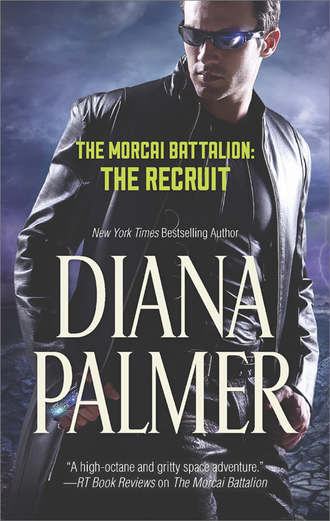

The Morcai Battalion: The Recruit

That was nonregulation, of course. All members of the Terravegan military were mentally neutered before they ever put on a uniform if they were slated for space duty. The authorities had decided that most conflicts were based on sexual or violent emotional issues. They simply used chemical means to remove the ability to bond from members of the military. But once in a while, a candidate fell through the cracks. Madeline was one. So was her father, Clinton Ruszel, a colonel in the SSC Paraguard Wing. Although she’d been reared in a government nursery, Madeline was one of the few children who actually knew one of her birth parents. Her father had contacted her when she was very small. In fact, he and Dtimun had saved her from terrorists in the Great Galaxy War. Dtimun didn’t look it, but he was eighty-nine human years of age. He could have passed for a human in his thirties. He was only in the middle years of his life, at that. He could look forward to another eighty-nine years or more before he died.

“You drifted off again,” Hahnson mused, tapping her on the hand.

“Oh! Sorry.” She smiled self-consciously. “I was thinking about...” She started to say Ahkmau, but that would have brought back really awful memories for all three of them. “I was thinking about how I ended up being the first woman on a Holconcom ship.”

Stern whistled through his teeth. “Now, there’s a story of legend.”

“You aren’t kidding,” Hahnson laughed. “Old Tnurat Alamantimichar, the Cehn-Tahr emperor, had a screaming fit about that.”

She grinned. “We heard that he sent the officer who reported my assignment to the brig for a standard month.”

“Well, the C.O. does do everything he can think of to tick off the emperor,” Hahnson commented. “They’ve had an ongoing feud for decades. Nobody knows what started it, but it’s heated up in the past few years. Your assignment to the Holconcom tied the old emperor up in knots. He can order people killed on Memcache, the home planet of the Cehn-Tahr,” he added, giving the true name of the race that humans in first contact had mistakenly called Centaurians, thinking they came from the star-system nearest old Earth.

“He’s an emperor,” Madeline pointed out. “Couldn’t he just order the C.O. to give me back to Lawson?”

“That’s a whole other story,” Hahnson mused. “You see, old Tnurat was the first commander of the Holconcom. He gave it, and its commander, absolutely autonomy during the Great Galaxy War and thereafter. He can’t command it. Neither can the Cehn-Tahr Dectat, their parliament. Dtimun has absolute authority.”

“I begin to see the light,” Madeline said, grinning. “Poor old emperor.”

“He is, sort of,” Hahnson said thoughtfully. “He only has one child left, a daughter, the princess we rescued from Ahkmau. All his sons are dead, including the one you tried to treat on Terramer, the day we met the Holconcom for the first time.”

“I’d forgotten that his son died that day. Does he have a wife?” She frowned. “Do Cehn-Tahr have wives, or do they have harems?” she continued absently.

“You’re our resident Cularian medicine specialist,” Stern pointed out. “Shouldn’t you know the answer to that?”

She gave him a droll look. “Cehn-Tahr social behaviors, and mating rituals, are forbidden knowledge. We aren’t even allowed to research them.” She had an angelic expression on her face.

Hahnson raised a blond eyebrow. “There are black-market vids that purport to explain them.”

She shifted some virtual paperwork. “I’ve heard about those.”

“Have you also heard that they’re filmed in a studio in Benaski Port by people who’ve never even seen a Cehn-Tahr?” Hahnson persisted.

She gasped. “They’re what? Those pirates!” she raged. “I paid two hundred mems for...for...” She broke off. They were giving her odd looks. She cleared her throat and lowered her voice. “I mean, why would someone pay so much money for misinformation?” she corrected innocently.

Her comrades laughed.

“There’s a much easier way. Ask the C.O.,” Stern suggested.

Madeline actually flushed. “Are you nuts? They’d space him for even listening to such a question. They’d space me for asking it.”

“I was assigned to medical duty with the Cehn-Tahr during the Great Galaxy War,” Hahnson recalled. His eyes lowered. “There are things humans are never allowed to learn about them.”

Madeline was openly curious. “Such as?”

He looked up and smiled sadly. “Just things.”

“Didn’t you learn something you could tell me?” she persisted.

He hesitated, as if weighing his answer. “Well, Cehn-Tahr mark their mates in some ancient rite of passage.”

Madeline was taking notes. “Mark them. How?”

Hahnson shook his head. “Don’t know. But it does leave a scar.” He lifted his eyebrows again. “Does that help?”

“Not a lot,” she sighed. She leaned her chin on her elbow. “Rojoks are a lot more forthcoming. But their customs aren’t the same as Cehn-Tahr. I mean, what if I ever have to treat a social disease or give counseling to a Cehn-Tahr woman? I’d be useless.”

“They don’t have social diseases,” Hahnson said. “Because they don’t frequent brothels. They’re amazingly pristine in their intimate habits. They also don’t mate outside their own species, ever. It’s a capital crime.”

“I know,” Madeline said quietly. Her companions tried not to notice the hollow tone of her voice. Her covert glances at the Holconcom C.O. hadn’t gone unnoticed by her longtime friends.

“Dr. Ruszel?” A small, pretty blonde woman in a green SSC Terravegan medical uniform popped her head in the door. Bright blue eyes glanced from one officer to the other. They lingered on Holt Stern just a few seconds too long for polite interest. “We’ve got an Altairian diplomat with a nasty cellulitis. Do you want to treat it, or shall I?”

Madeline smiled. Lieutenant (J.G.) Edris Mallory was a sweet woman. She’d actually started out in Cularian medicine on a military scholarship. But just after graduation from medical school, she’d wanted to become a breeder. In fact, she’d come back to the medical unit from a breeder colony after tests had found her ineligible as a host parent. Any slight defect in genetics could disqualify a candidate and Mallory had recessive genes whose inheritable traits—light eyes and hair—were out of fashion the year she applied. She’d been devastated by the rejection. She’d gone back to the military and been assigned to combat training. She’d even agreed to the mental neutering, dangerous in a woman of twenty. But she flunked out of combat school with the lowest score in academy history. After that, she landed in the SSC medical corps. Madeline liked her. She was a hard worker and she never shirked a task, even the unpleasant ones. She was only twenty-two. Ruszel, approaching thirty, found her shy presence comforting, in some odd way. She and Hahnson had conspired to protect Mallory from a Three Strikes provision, a covert and shaming law that could land an offender in stasis, to be used for medical experimentation. Mallory had two strikes already, and they kept a secret that could make it three. She was a sweet, kind woman.

“Go ahead, Edris,” she said. “I’ll be around if you need me.”

She grinned. “Thanks, Dr. Ruszel,” she said. “Hello, Doctor,” she greeted Hahnson warmly. She flushed a little as she glanced at Stern and then quickly away. “Captain.” She darted back through the door.

“She knows I’m a clone, doesn’t she?” Stern asked a little irritably. She’d barely looked at him.

“Oh, it’s not that.” She leaned toward him. “She’s shy. But she thinks you’re hot.”

He frowned. “It’s cool in here.”

“She thinks you’re desirable,” she corrected.

He flushed. “That’s not allowed.”

“She wanted to be a breeder,” she reminded him with a wicked grin. “But her genetics disqualified her to produce a child for the state, so when they expelled her from there, she decided to try combat medicine. She already had her degree in Cularian medicine.”

Stern glared. “How nice for her.”

Madeline shook her head. She knew it was the memory of Mary, his only love, that prompted that response. The original Stern, too, had come out of the neutering basically unaffected. He’d loved a woman named Mary who sacrificed her own life to save the lives of children. He carried a piece of blue velvet ribbon that had been attached to the posthumous medal they’d given her. He and Hahnson and Madeline passed it around between them as an accolade for heroic deeds. It was one of their best-kept secrets.

Hahnson’s wrist unit alarmed at the same time Madeline’s did. They looked at each other and grimaced.

“New medical transports are coming in from the occupied territories,” Madeline explained to Stern. “I guess we’ve got work again, Dr. Hahnson.”

“I guess we have, Dr. Ruszel,” he agreed. “Good thing we’re in port for a few days. Medical is overwhelmed already.”

“Mallory, casualties coming in!” Madeline called to Edris. “Call in all off-duty personnel, if you please.”

“Right away, Dr. Ruszel,” she replied.

“She and I are the only two Cularian specialists on the base until the graduates from the Tri-Fleet Medical Academy arrive,” Madeline commented. “I suppose we’ll do double duty again. Not that we get many wounded Rojok prisoners to treat.”

Stern was somber. “Good thing. Three cadets who were in the last firefight tried to break into sick bay and hang a wounded Rojok when the last medical transports came in.”

“Sadly for them, the commander was here reading me the riot act for another bar brawl when it happened,” Madeline recalled with a faint chuckle. “You never saw cadets run so fast. Pity they bothered. He had all three of them before they made the front door. They were so shaken up that the military police didn’t even have to cuff them.” She shivered with mock fear. “The C.O.’s pretty scary when he loses his temper.”

“To everybody else except you,” Hahnson mused, tongue-in-cheek. “He could space you if he wanted to. But all he ever does is ground you.”

She leaned forward. “He’s not sure that I didn’t sew up a boot or a glass of synthale inside him when I operated on him at Ahkmau,” she said with malicious humor. “He wouldn’t dare space me until he’s positive that I didn’t.”

“He keeps you for a pet,” Hahnson said with a chuckle.

“Eat worms, Hahnson.” Madeline made a face at him before she followed Mallory into sick bay.

CHAPTER TWO

SICK BAY WAS FULL. Not only were there combat casualties brought in from all parts of the battlefront, but a new type of influenza was making itself felt among members of the Tri-Galaxy Fleet. There was no vaccination so far, and hardly any treatment that worked.

“I remember Dr. Wainberg, head of the Exobiology Department at the Tri-Fleet Military Academy, lecturing us on viruses,” Madeline said as she and Edris Mallory worked side by side on combat wounds encountered by two Dacerian scouts who’d been ambushed near Terramer.

Edris laughed. “So do I. He and our human anatomy chief, Dr. Camp, gave lab exams that were, to say the least, challenging.”

Madeline grinned. “Challenging to cadets who thought they could pass those courses by dissecting holospecimens instead of the real thing. The medical sector didn’t tolerate slackers. They meant us to be taught proper surgical techniques, and we were.” She frowned. “You know, it’s still fascinating to me that viruses aren’t actually alive. They’re like a construct, an artificial construct.”

“Who knows,” Mallory agreed, “maybe they were originally part of some long forgotten engineered bioweapons tech.”

“Viruses are already dead, Mallory,” Madeline repeated.

Mallory frowned. “But, ma’am, how can they be dead if they were never alive?”

Madeline rolled her eyes. “That controversy still rages. They are alive in one sense, not in another. And I’m not joining that debate,” she added on a laugh. She finished a restructuring job and motioned for one of the medtechs to take the unconscious patient in his ambutube out to the floor. She stripped off her glove films and smiled at the younger woman. “We can debate that over a nice cup of java after lunch.”

The younger woman hesitated. Her blue eyes grew large. “Java? You don’t mean, real coffee?”

Madeline leaned closer. “I have it shipped in illegally from the Altairian colony on Harcourt’s Planet,” she confided. “Then I grind the beans and brew it in my office.”

“Coffee.” Mallory’s mouth was watering. “I dream about it. What passes for coffee in the mess hall is an insult to a delicate palate.”

“I agree.”

She pursed her lips. “Ma’am, are you going to tell me something I won’t want to hear? Is that why I’m being treated to such a luxury?”

“You have a suspicious mind,” her colleague replied. “Hurry up. We don’t have a lot of time. There’s a medical transport coming in from Terramer in about a standard hour and we may have more work.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“I have to go over to Tri-Fleet HQ and report to the commander about this latest batch of casualties. You can flash me if there’s anything urgent before I get back.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

* * *

MADELINE LOCATED DTIMUN in his temporary office at Tri-Fleet HQ. It was smaller and more cramped than the one he maintained aboard the Morcai, but closer to fleet operations.

He frowned when she was admitted. “You have never reported to me directly on battle casualties. Is there a reason for this deviation from protocol?”

“Yes, sir,” she said, standing at parade rest. “It’s about Mallory.”

His eyebrows lifted.

“Lieutenant J.G. Edris Mallory?” she prompted. “My assistant?”

“Yes. What about her?”

“Sir, she needs to be familiarized with the routine aboard ship, in case I ever have to bring her with me on a mission.”

He stood up, cold and unapproachable. “I will not authorize the presence of a second human female aboard my flagship,” he said flatly.

“Only to observe,” she persisted. She let out an exasperated sigh. “What if I were captured by Rojoks on the battlefield?”

“I would send them my condolences,” he returned.

She glared at him. “You’d have nobody aboard who could save you from a health crisis,” she tossed back.

“It amazes me that you have never questioned the reason I carry no complement of Cehn-Tahr medics aboard the Morcai.”

She blinked. “They said you had a fine contempt for medics of your own species. I assumed that was the explanation.”

His eyes narrowed and became a steady, searching blue as they explored her face. “You know nothing about us except what we permit you to know.”

“You can pin a rose on that,” she returned bluntly. “I’ve had to resort to black market vids to find out anything at all about Cehn-Tahr society.”

His eyes flashed green with humor. “Those vids are made at Benaski Port...”

“...by pirates who never saw a live Cehn-Tahr, yes, I know. Hahnson informed me after it was too late to demand my money back!” she muttered.

The green grew broader in his eyes. He cocked his head. “It did not occur to you to ask me?”

She cleared her throat. “I wouldn’t dare!”

“I have found very little that you would not dare, Ruszel,” he retorted.

She shifted restlessly and averted her eyes. It would be embarrassing, even for a physician, to put any of her burning questions to him.

“I realize that,” he said softly.

She grimaced. “I wish you wouldn’t walk in and out of my mind, sir. It’s very disconcerting.”

“You are far too easy to read,” he pointed out. “Telepaths learn to block unwanted intrusions at a very early age.”

She lifted her eyes to his, searching them quietly. “You healed the little Altairian child with nothing more than your mind,” she recalled. “I’ve never spoken of it, but I think your mental abilities are greater than you allow us to see.”

“Much greater,” he said in her mind.

“You keep secrets very well, as a species,” she pointed out.

“Some are best kept,” he returned silently. “If your species knew the true nature of mine, few humans would feel secure enough to serve with us.”

That was a revelation. It disturbed her at some deep level. “We’ve seen you fight,” she said, assuming that was what he referred to.

His eyes became solemn. “You have seen a greatly restrained version of our fighting style,” he said surprisingly. “We modified it for the benefit of our human crewmen.” He looked at her closely. “Why do you think our emperor was able to conquer over one hundred and fifty worlds with little more than the Holconcom?”

That was a question she’d never asked. “I never thought about it, sir.”

“Some races who were victims of his first conquests still remember the Holconcom attacks. The fear alone kept them in line. It does, even today.” His face grew hard. “We are an aggressive, violent species. Mercy is unknown to us.”

“My little Altairian patient might disagree with you,” she said, smiling in memory.

“The child was not my enemy,” he pointed out.

She studied his hard face in silence. “Why don’t you want other races to know anything about your society?”

“It would serve no useful purpose,” he said curtly. “We never mate outside our own species.”

She felt cold inside. She wasn’t quick enough to divert her mind. He saw the sadness, and understood it all too well.

His eyes narrowed. “You are a fragile race,” he said.

She stared at him, uncomprehending. “I could remind you that I took down several Rojok soldiers when we were in Ahkmau.”

“I could remind you that only Chacon’s intervention saved your life during the escape.”

“Rub it in,” she muttered, flushing. “I was intent on saving a patient. I didn’t see the Rojoks rushing me.”

“Your impulsive nature could lead you to tragedy,” he said. “You must exhibit more control of yourself.”

“I do try, sir. But human nature is what it is. We can’t change what we are.”

He grew contemplative. “No,” he said, an odd bitterness in his tone. “We cannot.”

“About Mallory, sir...”

“You can use the comps to give her a virtual tour of the ship,” he said firmly. “I do not need any more distractions aboard. You and your temper provide quite enough already.”

“My temper?” she exclaimed. “Look who’s talking!”

“Remember to whom you are speaking!” he shot back.

“I didn’t break a Gresham in half with my bare hands when I lost my patience...!”

“Dismissed!”

She almost bit her tongue off keeping the reply back that she wanted to make. She saluted sharply, turned and marched out of the office. Behind her, she heard muffled curses in Cehn-Tahr, and marched faster.

* * *

LIEUTENANT (J.G.) EDRIS MALLORY’S expression was one of pure joy as she sipped the illegal caffeine in Madeline’s office. The use of stimulants, even natural ones, was prohibited by Tri-Fleet regulations. Not that anyone enforced the law, especially since Admiral Lawson himself sneaked in java from the Altairian colonies. Of course, he was an admiral and could get away with it. Madeline might not fare as well.

Edris closed her eyes and savored the taste and scent as she lifted her head. “Oh, bliss,” she sighed.

Madeline laughed. “It is pretty special, out here in the big black, isn’t it? We’re so far away from anything that can’t be grown in solution.” She sipped her own coffee. “I have to talk to you about something.”

Edris grimaced. “I’ve screwed up again, haven’t I?” she asked. “I’m just not suited to life in our present age, you know. I washed out of combat school with a memorable low grade, after I couldn’t get accredited as a breeder. Now here I am doing combat medicine, and I fumble more than I fix...”

“You’re doing well,” Madeline interrupted. “All you lack is confidence in your own abilities. Well, that,” she added hesitantly, “and the ability to talk back to people. To the Cehn-Tahr specifically.”

The slender young blonde moved restlessly in her chair. “They’re very intimidating, especially the Holconcom commander,” she replied. “He glares.”

“You have to learn to glare back,” Madeline told her. “They’re a misogynist culture. Their own women are denied access to the military, much less combat. The Cehn-Tahr think our military is mad to permit women to serve in it, mentally neutered or not.”

Edris finished the last precious drop of her coffee. “I’m just glad it’s you and not me serving aboard the Morcai.”

“That’s what I want to talk to you about,” Madeline told her. “Since Holmes and Watts shipped out, you and I are the only experienced Cularian specialists on base right now. There are twenty in graduate school, four of whom are due to be assigned to Trimerius when they graduate. But if something happens to me, you’re the only backup around.”

“Nothing will happen to you, ma’am,” Edris assured her with a smile. “You’re one of the bravest people I know.”

Madeline hesitated. “Anyone can die. The Holconcom can’t function without a medic who can operate on Cehn-Tahr soldiers in an emergency. The commander hates medics as a rule, and he won’t permit the Dectat to assign physicians to him. He’s reluctant to have me aboard, but Ahkmau convinced him that it was lunacy not to carry a Cularian specialist into battle.”

“He scares me to death,” Edris commented, wrapping her arms around her slender figure. “I don’t know what I’d do, if I ever had to substitute for you in the Holconcom.”

“That’s just the point. The commander agrees with me, that we need to start letting you come with us on certain missions aboard the Morcai so that you can get used to the routine aboard ship.” She deliberately didn’t meet Mallory’s eyes as she lied to her. It was in a good cause.

Edris lost two shades of color. “No,” she said at once. “Oh, no, I can’t do that. I can barely manage here, when you’re away with the unit. I could never...I mean, I can’t...”

“You can,” Madeline said, and in a tone that didn’t brook argument. “You got through medical school. You’ll adapt to the Morcai.”

Edris bit her lower lip. She looked hunted.

“They’re just men,” she said, exasperated. “Alien men, but males are pretty much the same anywhere.”

“Not the Cehn-Tahr,” Edris argued. “I’ve heard stories.”

Madeline raised both eyebrows.

Edris hesitated, but the gossip was too juicy not to share. “They say,” she said in a conspiratorial tone, “that a Cehn-Tahr soldier ate a young Jebob recruit during the Great Galaxy War...ma’am?”

Madeline was doubled over, laughing. That story had gone through the ranks over the years like a fever. Some people did actually believe it.

“Well, they said,” Edris said defensively.

“Edris,” Madeline replied, wiping away tears of near hysteria, “I can give you proof that no Cehn-Tahr has ever eaten another soldier.”

“You can?”

“The C.O. has never eaten me,” she reminded her colleague. “And nobody over the years has given him more cause.”

“You do wear on his nerves, I hear.”

Madeline laughed. “His nerves, his temper, his patience. He’s dressed me down, grounded me, brigged me on occasion,” she recalled. “But he’s never taken a bite out of me.”

That was true. The battles between the commander of the Holconcom and his chief medic had assumed the mantle of legend. Once, Madeline had followed Dtimun off the ship raging about his refusal to let her suture a bone-deep wound in his leg. He trailed blood out the airlock and just kept walking, even when she threw a cyberclamp after him in impotent rage.

“Isn’t it amazing that he never busted you in rank?” Edris mused.

“He did try,” Madeline assured her. “But my father is a colonel in the Paraguard Wing and best friends with Admiral Lawson. They ganged up on the commander and refused to let the demotion go through.” She grinned. “The C.O. was livid! And did he get even! He requisitioned my billet for storage and I had to sleep in the cargo hold for a solid week. He only relented when I borrowed a player from Hahnson and flooded the hold with ancient human drum and bagpipe music.”